Introduction: A Force in German Modernism

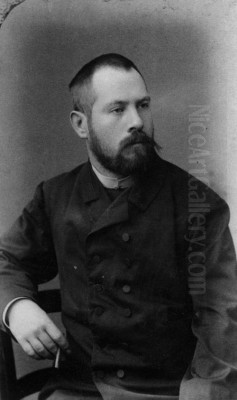

Lovis Corinth stands as one of the most significant and complex figures in German art at the turn of the 20th century. Born Franz Heinrich Louis Corinth on July 21, 1858, in Tapiau, East Prussia (now Gvardeysk, Russia), and passing away on July 17, 1925, in Zandvoort, Netherlands, his life and career spanned a period of dramatic artistic upheaval. Corinth was a prolific painter, printmaker, and writer whose work navigated the currents shifting from 19th-century Realism and Impressionism towards the raw energy of Expressionism. He absorbed traditions yet forged a unique path, characterized by vigorous technique, emotional intensity, and an often-unflinching look at the human condition. His art remains a powerful testament to a period of transition, embodying both the sensual celebration of life and a profound awareness of its fragility.

Corinth's artistic journey was marked by rigorous academic training, exposure to the avant-garde scenes in Munich and Paris, and a pivotal role in the Berlin Secession, an artist-led group challenging the conservative art establishment. His subject matter was diverse, encompassing powerful portraits and self-portraits, lush landscapes, dynamic still lifes, robust nudes, and dramatic interpretations of biblical and mythological themes. A debilitating stroke later in life dramatically altered his style, pushing it towards an even greater expressive freedom that cemented his place, albeit sometimes reluctantly acknowledged by the artist himself, within the broader Expressionist movement alongside figures like Edvard Munch and the artists of Die Brücke.

Early Life and Academic Foundations

Corinth's artistic inclinations emerged early. Growing up in East Prussia, he received initial encouragement and began formal studies at the Königsberg Academy of Art in 1876. There, he studied under Otto Günther, a genre painter associated with the Düsseldorf school, who instilled in him a foundation in realistic depiction. This early training emphasized careful observation and technical proficiency, grounding Corinth in the academic traditions prevalent in Germany at the time. However, the young artist was already showing signs of an independent spirit and a robust temperament that would later define his mature work.

Seeking broader horizons, Corinth moved to Munich in 1880, then a major German art center rivaling Berlin and Düsseldorf. He enrolled at the Academy of Fine Arts, studying under figures like Franz von Defregger and Ludwig von Löfftz. Munich exposed him to a richer artistic milieu, including the naturalistic tendencies influenced by Wilhelm Leibl and his circle, who advocated for direct painting from life, often inspired by the realism of Gustave Courbet. While absorbing these influences, Corinth began developing a more painterly approach, with looser brushwork and a growing interest in the effects of light, hinting at the Impressionistic developments occurring elsewhere in Europe.

Parisian Exposure and Developing Style

Like many ambitious artists of his generation, Corinth sought experience in Paris, the undisputed capital of the art world. He studied intermittently at the Académie Julian between 1884 and 1887, a private art school popular with foreign students. His teachers there included Tony Robert-Fleury and William-Adolphe Bouguereau. While Bouguereau represented the pinnacle of French academicism, with its polished finish and idealized subjects, the Académie Julian also offered a relatively liberal environment. More importantly, Paris exposed Corinth directly to the revolutionary movements transforming French art.

During his time in Paris, Corinth encountered the works of the Impressionists, such as Claude Monet, Edgar Degas, and Pierre-Auguste Renoir, although his initial reaction was reportedly mixed. He was perhaps more immediately drawn to the robust realism of painters like Gustave Courbet and the bold compositions and modern subjects of Édouard Manet. This period was crucial for broadening his technical palette and understanding of color and light, even if he didn't fully embrace the Impressionist aesthetic immediately. He began incorporating a brighter palette and more visible brushstrokes into his work, moving further away from the darker tones of the Munich school.

Return to Germany: Munich and the Secessionist Spirit

Upon returning to Germany, Corinth initially settled back in Munich in 1891. The city was experiencing its own artistic ferment with the founding of the Munich Secession in 1892, led by artists like Franz von Stuck, Fritz von Uhde, and Max Liebermann (though Liebermann would soon become more associated with Berlin). The Secession movements, arising also in Vienna and Berlin, represented a break from the conservative, state-sponsored art academies and exhibition systems. They championed artistic freedom, individualism, and newer styles like Impressionism and Symbolism.

While Corinth was not initially a leading member of the Munich Secession, he participated in its exhibitions and absorbed the progressive atmosphere. His work from this period shows a continued engagement with naturalism but with increasing boldness. He painted portraits, genre scenes, and large-scale historical or mythological subjects, often characterized by a fleshy, vigorous realism that sometimes bordered on the provocative. His handling of paint became more confident and textured, distinguishing his work from the smoother finish of academic painting and the lighter touch of French Impressionism. He began to establish a reputation, albeit one sometimes marked by controversy due to the perceived earthiness or brutality of his depictions.

Berlin: Leadership and Artistic Maturity

In 1901 or 1902, Corinth made a decisive move to Berlin. The German capital was rapidly becoming the nation's cultural and artistic hub. He joined the Berlin Secession, which had been founded in 1898 under the leadership of Max Liebermann, Walter Leistikow, and Max Slevogt. These three artists are often considered the main proponents of German Impressionism, adapting the French style to a German sensibility, often with stronger drawing and sometimes darker palettes. Corinth quickly became a prominent figure within the Secession.

In Berlin, Corinth opened a private painting school for women, where he met his future wife, Charlotte Berend, one of his first students. Charlotte Berend-Corinth (1880-1967) became an accomplished artist in her own right, as well as his model, muse, and manager. Their family life would become a recurring and intimate theme in his work. Corinth's art flourished in the dynamic environment of Berlin. His style synthesized elements of Realism and Impressionism into a powerful, uniquely German idiom. His brushwork was energetic, his colors rich and often applied thickly, conveying a strong sense of physical presence and vitality.

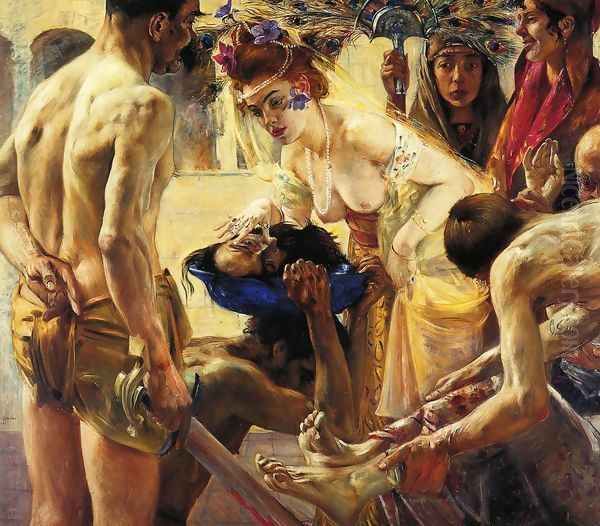

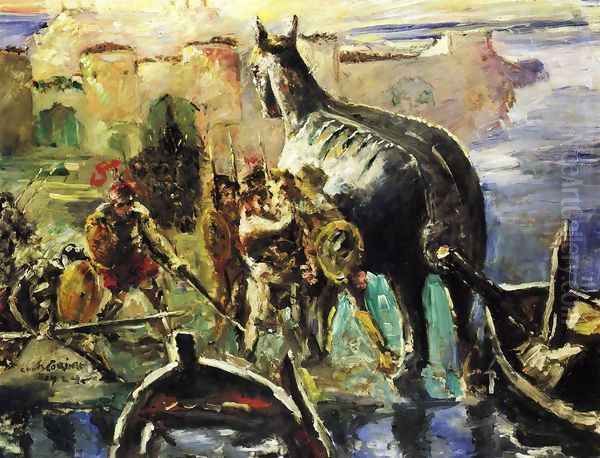

Corinth's subjects during his mature Berlin period were diverse. He excelled at portraiture, capturing not just likeness but also the psychological depth of his sitters, including prominent figures from Berlin's cultural scene. His self-portraits became a lifelong practice, offering an unsparing chronicle of his own physical and emotional state. He continued to paint nudes, often unidealized and rendered with a raw sensuality that challenged conventional notions of beauty. Mythological and biblical scenes were tackled with dramatic intensity, focusing on moments of violence, passion, or psychological turmoil, drawing comparisons to Old Masters like Rembrandt van Rijn and Peter Paul Rubens in their ambition and emotional force. Works like Salome (1900) or Blind Samson (1912) exemplify this powerful, often unsettling, approach.

Corinth's standing within the Berlin Secession grew, and following internal disputes and Liebermann's resignation, Corinth was elected president in 1911 (and again later). This placed him at the forefront of the German avant-garde, although the Secession itself was facing challenges from the younger, more radical generation of Expressionists, such as the artists of Die Brücke (The Bridge) – Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Erich Heckel, and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff – who briefly exhibited with the Secession before forming their own group, the New Secession, alongside artists like Emil Nolde.

The Stroke and the Shift Towards Expressionism

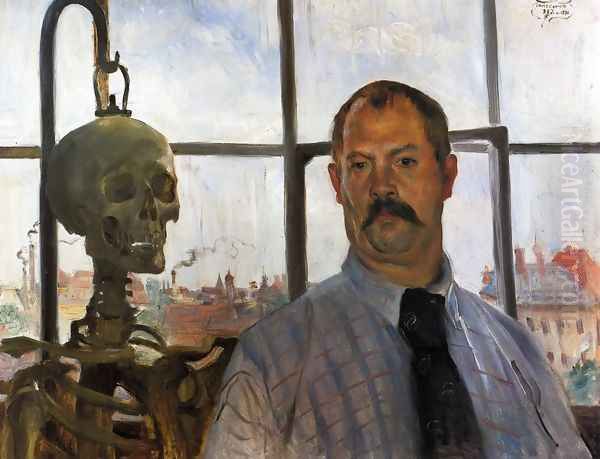

In December 1911, Corinth suffered a severe stroke that left him partially paralyzed on his right side. This event marked a profound turning point in his life and art. Facing physical limitations and the specter of mortality, Corinth fought his way back to painting, learning to adapt his technique. While devastating, the stroke paradoxically seemed to unleash an even greater expressive power in his work. His brushwork became looser, more agitated, and seemingly more spontaneous. The forms in his paintings sometimes appear fragmented or distorted, charged with an emotional intensity that aligns his late work closely with Expressionism.

Although Corinth himself often expressed skepticism about Expressionism as a movement and maintained connections to Impressionist principles of observing nature, his post-stroke paintings are widely considered among the most powerful examples of German Expressionist art. The struggle and vulnerability he experienced are palpable in his numerous late self-portraits, such as the famous Self-Portrait with Skeleton (1921), where he confronts his own mortality with characteristic directness, echoing a long tradition of memento mori images but rendered with modern psychological intensity.

His landscapes, particularly the extensive series painted at the Walchensee, a lake in the Bavarian Alps where he spent summers from 1918 onwards, became a major focus of his late career. These works are celebrated for their vibrant color, dynamic compositions, and the way they capture the changing moods of nature with raw energy. The Walchensee paintings represent a deeply personal connection to the landscape, rendered not with Impressionistic detachment but with an immersive, almost ecstatic fervor. They stand alongside the landscapes of artists like Emil Nolde or even Oskar Kokoschka in their expressive force, though Corinth's connection to observed reality remained stronger.

Master of the Graphic Arts

Alongside his prolific output as a painter, Lovis Corinth was a highly accomplished and equally prolific printmaker. He mastered various techniques, including drypoint, etching, and lithography, and produced hundreds of graphic works throughout his career. His prints often explore the same themes as his paintings – portraits, nudes, biblical and mythological scenes, landscapes, and still lifes – but the graphic medium allowed for different kinds of expression, often emphasizing line, contrast, and dramatic composition.

His drypoints, in particular, are noted for their rich, velvety lines and tonal depth, achieved by the burr raised on the copper plate during incision. His etchings could be delicate or fiercely energetic, while his lithographs allowed for a more painterly approach to printmaking, with broad tonal areas and fluid lines. Works like the lithograph portfolio Antique Legends (Antike Legenden) or the powerful print Bacchanal (1913) showcase his ability to convey intense emotion and dynamic movement within the constraints of black and white. His graphic work stands comparison with other great painter-printmakers like Rembrandt, Francisco Goya, and Edvard Munch, demonstrating his versatility and commitment to exploring different artistic means.

Recurring Themes: Flesh, Spirit, and Nature

Throughout his diverse body of work, certain themes recur with particular intensity in Corinth's art. The human figure, especially the nude, was a constant preoccupation. Unlike the idealized nudes of academic tradition or the flattened forms of some modernists, Corinth's nudes are often fleshy, substantial, and intensely physical. They celebrate the sensuousness of the body but can also convey vulnerability, awkwardness, or raw power. His approach was direct and unsentimental, sometimes shocking to contemporary audiences but deeply rooted in a Northern European tradition of realism found in artists like Albrecht Dürer or Hans Baldung Grien.

Portraiture, especially self-portraiture, was another central pillar of his oeuvre. His self-portraits form an extraordinary visual autobiography, tracking his physical aging, his changing psychological states, his confidence, his struggles after the stroke, and his confrontation with mortality. They reveal an artist constantly interrogating his own identity and existence with unflinching honesty. His portraits of others, including his wife Charlotte Berend-Corinth and their children, often possess a similar psychological insight and warmth, rendered with his characteristic vigorous brushwork.

Religious and mythological subjects provided Corinth with vehicles for exploring universal human dramas – passion, suffering, violence, and ecstasy. He approached these traditional themes with a modern sensibility, stripping away sentimentality to focus on the raw emotional core. His depictions, such as Descent from the Cross or The Trojan Horse, are often characterized by dynamic compositions, dramatic lighting reminiscent of Baroque masters, and a visceral rendering of flesh and emotion that makes these ancient stories feel immediate and relevant.

Finally, landscape, particularly in his later years, became a crucial outlet for his expressive energy. The Walchensee paintings are not merely topographical records but intense emotional responses to the natural world. He captured the shifting light, the turbulent weather, and the sublime power of the Alpine scenery with a palette of vibrant, often non-naturalistic colors and agitated brushstrokes that convey a sense of pantheistic immersion in nature. These late landscapes are among his most celebrated works and represent a culmination of his journey towards expressive freedom.

Reception, Controversy, and Enduring Legacy

During his lifetime, Lovis Corinth achieved significant recognition within Germany, particularly through his leadership role in the Berlin Secession. However, his work also provoked controversy. Its raw energy, unidealized figures, and sometimes violent subject matter challenged conservative tastes. Critics like the influential Danish writer Georg Brandes famously described one of Corinth's self-portraits as a form of "self-punishment," reflecting the unease his work could inspire. While respected by fellow artists and progressive critics, he did not achieve the widespread international fame of some of his French contemporaries during his lifetime. His work received limited exposure in the United States, for example, until well after his death.

The rise of Nazism in Germany cast a dark shadow over Corinth's legacy. Although he died in 1925, before the Nazis came to power, his art, along with that of most modern German artists including Max Beckmann, Ernst Barlach, Käthe Kollwitz, and members of the Bauhaus like Paul Klee and Wassily Kandinsky, was deemed "degenerate" (Entartete Kunst) by the regime. Hundreds of his works were confiscated from German museums in 1937, some were sold abroad, and others were likely destroyed. This official condemnation temporarily obscured his importance in German art history.

After World War II, however, Corinth's reputation was gradually rehabilitated and grew steadily. He came to be recognized as a major figure bridging the 19th and 20th centuries, a crucial link between German Impressionism and Expressionism. His technical virtuosity, the emotional depth of his work, and the sheer power of his artistic personality secured his place in the canon of modern art. His influence can be seen in the work of later German artists, particularly the Neo-Expressionists of the late 20th century, such as Georg Baselitz and Anselm Kiefer, who admired his painterly vigor and psychological intensity.

Today, Lovis Corinth's paintings and prints are held in major museums worldwide, including the Tate Modern in London, the Musée d'Orsay in Paris, the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Art Institute of Chicago, and numerous institutions in Germany, such as the Bavarian State Painting Collections in Munich and the Nationalgalerie in Berlin. Retrospectives of his work continue to draw attention to the richness and complexity of his achievement. He is remembered not just as a painter of technical brilliance but as an artist who grappled profoundly with the fundamental experiences of life, death, sensuality, and spirituality, leaving behind a body of work that remains compelling and relevant.

Conclusion: A Titan of Transition

Lovis Corinth remains a towering figure in German art history, an artist whose work embodies the turbulent transition from the certainties of the 19th century to the fragmented dynamism of the 20th. He successfully synthesized the lessons of Realism and Impressionism, forging a powerful, personal style characterized by vigorous brushwork, rich color, and profound emotional depth. His leadership in the Berlin Secession placed him at the center of the German avant-garde, while his prolific output across painting and printmaking demonstrated remarkable versatility and energy.

The stroke he suffered in 1911, rather than ending his career, catalyzed a transformation towards an even more expressive and emotionally charged style, aligning his late work with the major currents of Expressionism. Through his unflinching self-portraits, his robust nudes, his dramatic narrative scenes, and his ecstatic late landscapes, Corinth explored the complexities of the human condition with rare honesty and power. Though sometimes overshadowed internationally by his French contemporaries or the more radical German Expressionists, Lovis Corinth's unique synthesis of tradition and modernity, observation and emotion, makes him an indispensable figure for understanding the development of modern art in Germany and beyond. His art continues to resonate with its visceral energy and its profound engagement with life in all its intensity.