Giorgio Vasari stands as a pivotal figure in the Italian Renaissance, a man whose talents spanned painting, architecture, and writing. Born in Arezzo, Tuscany, on July 30, 1511, and passing away in Florence on June 27, 1574, Vasari's life coincided with a period of extraordinary artistic flourishing. While a respected artist and architect in his own right, his most enduring legacy lies in his seminal work, Le Vite de’ più eccellenti pittori, scultori e architetti (Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects), a collection of biographies that effectively founded the discipline of art history. His influence extended through his artistic creations, his organizational efforts in founding the first art academy, and his close association with the powerful Medici family.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Giorgio Vasari hailed from Arezzo, a town steeped in Tuscan tradition. His family background was rooted in craftsmanship; his father, Antonio Vasari, and mother, Maddalena Tacci, came from a line of potters. This early exposure to artisanal work may have instilled in him an appreciation for skill and technique. Recognizing his burgeoning talent, Vasari was sent to Florence at a young age, the vibrant heart of the Renaissance, to further his artistic education.

In Florence, the young Vasari entered a world teeming with artistic giants and intense creative energy. He had the invaluable opportunity to study and work under prominent masters. His training included time in the workshop of Andrea del Sarto, a leading painter of the High Renaissance in Florence, known for his harmonious compositions and masterful use of color. This apprenticeship provided Vasari with a strong foundation in Florentine painting techniques and aesthetics.

He also spent time in the circle of Baccio Bandinelli, a sculptor known for his rivalry with Michelangelo. Though Vasari would later express reservations about Bandinelli's style, this exposure broadened his understanding of different artistic approaches and the competitive atmosphere of the Florentine art scene. Furthermore, Vasari developed a close friendship and working relationship with Francesco Salviati, another significant Mannerist painter. Together, they reportedly studied ancient Roman art and the works of Renaissance masters in Rome, deepening their classical knowledge and technical skills.

Crucially, Vasari came into contact with the towering figure of Michelangelo Buonarroti early in his career. While perhaps not a formal apprentice in the traditional sense for an extended period, Vasari developed a profound admiration for Michelangelo, viewing him as the pinnacle of artistic achievement. This reverence would shape Vasari's own artistic outlook and become a central theme in his later writings. His early experiences in Florence and Rome, learning from masters like Andrea del Sarto and interacting with figures like Michelangelo and Salviati, were fundamental in shaping his multifaceted career.

A Prolific Painter of the Mannerist School

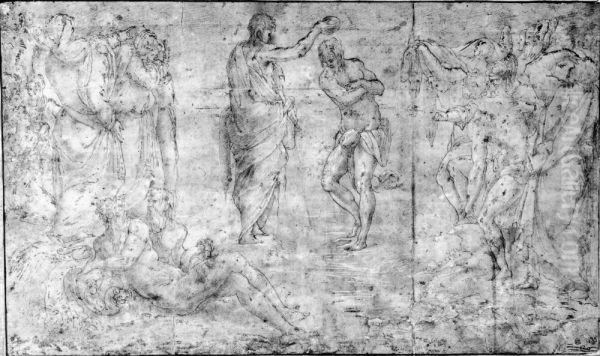

Giorgio Vasari was an active and successful painter, firmly situated within the Mannerist style that emerged after the High Renaissance. Mannerism, characterized by its elegance, complexity, artificiality, and intellectual sophistication, often featured elongated figures, intricate compositions, and vibrant, sometimes non-naturalistic colors. Vasari embraced these elements, becoming a prominent exponent of the style, particularly in Florence under the patronage of the Medici.

His painting commissions were numerous, ranging from altarpieces and portraits to large-scale decorative fresco cycles. Working extensively for Duke Cosimo I de' Medici, Vasari contributed significantly to the decoration of the Palazzo Vecchio, Florence's town hall, which the Duke had transformed into his residence. These frescoes often depicted historical and allegorical scenes celebrating the Medici dynasty and Florentine history, executed with the characteristic Mannerist flair for elaborate detail and dynamic, often crowded, compositions.

Among his notable individual paintings is the Portrait of Alessandro de' Medici (though sometimes identified as Lorenzo), showcasing his skill in capturing a likeness while imbuing the subject with aristocratic poise. Works like Perseus and Andromeda exemplify the Mannerist fascination with mythology and dramatic narrative, often featuring contorted poses and a heightened sense of artificiality that emphasized artistic skill (maniera).

Religious themes also occupied a significant portion of his output. The Martyrdom of St. Stephen demonstrates his ability to handle complex multi-figure compositions and convey intense emotion, albeit filtered through the elegant lens of Mannerism. His Entombment similarly tackles a poignant religious subject with dramatic lighting and expressive, though stylized, figures. These works reveal his deep engagement with the artistic currents of his time, reflecting the influence of masters like Michelangelo and Raphael, yet interpreted through his distinct Mannerist sensibility.

Vasari's painting style was often characterized by its facility and speed of execution, necessary for completing the large fresco cycles demanded by his patrons. While sometimes criticized for lacking the profound depth or naturalism of High Renaissance masters, his work consistently displayed technical proficiency, sophisticated design (disegno), and a clear narrative intent, perfectly suited to the decorative and propagandistic needs of his Medici patrons.

Vasari the Architect: Shaping Florentine Spaces

Beyond his accomplishments as a painter, Giorgio Vasari made significant contributions as an architect, leaving an indelible mark on the urban landscape of Florence and beyond. His architectural work, like his painting, was often undertaken in service of the Medici Dukes, particularly Cosimo I, reflecting the Mannerist penchant for integrated artistic projects that combined structural design with elaborate decoration.

His most famous architectural achievement is undoubtedly his work on the Uffizi Palace in Florence. Commissioned by Cosimo I to house the Florentine magistrates and administrative offices (uffici), Vasari designed a long, narrow courtyard complex connecting the Palazzo Vecchio to the River Arno. The Uffizi's elegant loggias, rhythmic facade with repeating bays, and use of classical orders created a harmonious and imposing civic space, embodying principles of order and grandeur.

Integral to the Uffizi project was the design of the Vasari Corridor (Corridoio Vasariano). This enclosed passageway, built in just five months in 1565, stretches over the Ponte Vecchio and through existing buildings, connecting the Uffizi (and thus the Palazzo Vecchio) to the Pitti Palace, the Medici's residence across the Arno. It served as a private walkway for the Duke, symbolizing his power and providing security, while also offering unique views of the city. It remains a remarkable feat of engineering and urban planning.

Vasari also undertook significant renovations within the Palazzo Vecchio itself, adapting the medieval structure to serve as the ducal palace. This involved creating new apartments, grand halls like the Salone dei Cinquecento (which he decorated with vast frescoes), and studioli, integrating his architectural modifications with his extensive painted decorations.

His architectural influence extended to religious buildings as well. He was involved in the controversial remodeling of the interiors of medieval churches like Santa Croce and Santa Maria Novella in Florence. This involved removing choir screens and relocating tombs to create more open spaces suitable for Counter-Reformation liturgical practices, a process that, while reflecting contemporary needs, also resulted in the loss of earlier artworks and structures.

In his hometown of Arezzo, Vasari designed and built his own house, now the Casa Vasari museum. He meticulously decorated its rooms with frescoes celebrating art and artists, creating a personal testament to his ideals. His architectural work, characterized by its classical vocabulary adapted with Mannerist sophistication and its integration with painting and sculpture, demonstrates his versatility and his key role in shaping the physical environment of Medicean Florence.

The Lives: Crafting the Canon of Art History

Giorgio Vasari's most monumental achievement, the one that secured his lasting fame far beyond his artistic output, is his book Le Vite de’ più eccellenti pittori, scultori e architetti (Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects). First published in Florence in 1550 and significantly expanded and revised in a second edition in 1568, this work is widely considered the foundation stone of modern art history.

The Lives presents a series of biographies of Italian artists, beginning with the late medieval precursors like Cimabue and Giotto, whom Vasari credited with reviving art after a period of decline following antiquity. It progresses through the masters of the 15th century (Quattrocento) like Masaccio, Donatello, and Brunelleschi, culminating in the High Renaissance titans Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael, and, presented as the ultimate peak of artistic perfection, his idol Michelangelo. The second edition extended the coverage to include artists of Vasari's own generation and even a section on living artists (including himself).

Each biography typically includes details about the artist's birth, training, personality, major works, and death, often enlivened with anecdotes, legends, and critical assessments. Vasari structured his narrative around a biological metaphor of art's rebirth, growth, and maturity, seeing a clear progression towards the perfection achieved in his own time, particularly in Florence. He emphasized the importance of disegno – a concept encompassing both drawing and intellectual design – as the fundamental principle underlying all the visual arts: painting, sculpture, and architecture.

The scope of the Lives was unprecedented. By systematically collecting information, describing artworks (many of which he knew firsthand), and attempting to create a coherent historical narrative, Vasari provided the first comprehensive overview of the development of Italian Renaissance art. He established a canon of artists and artworks that profoundly shaped subsequent understanding and appreciation of the period. His vivid prose and engaging storytelling made the lives of these artists accessible and memorable.

Content and Concepts within The Lives

Vasari's Lives is far more than a simple collection of biographies; it is imbued with his own theories, biases, and a distinct historical vision. He organized the work chronologically and geographically, dividing the development of art since the "revival" under Cimabue and Giotto into three ages or periods, roughly corresponding to the 14th, 15th, and 16th centuries. This periodization, culminating in the "perfection" of Michelangelo, became a standard model for discussing Renaissance art.

Central to Vasari's framework was the concept of disegno. In the introductions to the Lives and woven throughout the biographies, he argued that drawing and design were the intellectual foundation connecting painting, sculpture, and architecture. This emphasis elevated the status of the artist from mere craftsman to intellectual creator, capable of mastering multiple disciplines through a shared theoretical underpinning. This concept also supported his efforts, alongside others, in founding the Accademia del Disegno in Florence in 1563, Europe's first formal art academy, intended to provide theoretical and practical instruction.

The Lives is rich in detail, describing specific techniques, workshop practices, and the social context in which artists operated. Vasari included discussions of patronage, competition between artists, and the relationship between art and classical antiquity. He often incorporated anecdotes, some perhaps apocryphal but serving to illustrate an artist's character or a particular point about their work. The famous story of the young Leonardo da Vinci's angel in Verrocchio's Baptism of Christ causing Verrocchio to abandon painting comes from Vasari, highlighting Leonardo's precocious genius.

However, Vasari's narrative is not objective. He displayed a strong bias towards Florentine artists, often downplaying or criticizing achievements from other Italian centers like Siena or Venice. His admiration for Michelangelo bordered on hagiography, presenting him as divinely inspired. His accounts could also be colored by personal friendships or rivalries; his descriptions of artists he knew, like Andrea del Sarto or Francesco Salviati, are particularly vivid, though not always impartial. He sometimes relied on hearsay or embellished facts for dramatic effect.

The Enduring Significance and Influence of The Lives

Despite its biases and occasional inaccuracies, the impact of Vasari's Lives on the study and perception of art has been immense and enduring. It essentially created the blueprint for art historical writing, establishing the biographical approach combined with stylistic analysis as a primary methodology for centuries. It provided the first coherent narrative of the Italian Renaissance, popularizing the very idea of a distinct artistic "rebirth" following the Middle Ages.

The Lives shaped the canon of Renaissance art, determining which artists were considered major figures and influencing how their contributions were understood. The triad of Leonardo, Raphael, and Michelangelo as the supreme masters of the High Renaissance owes much to Vasari's presentation. His work became the principal source of information about countless artists and artworks, many of which might otherwise have been forgotten or poorly documented. For generations of scholars, collectors, and travelers undertaking the Grand Tour, Vasari was the indispensable guide to Italian art.

His emphasis on disegno and the intellectual status of the artist contributed significantly to the elevation of the visual arts during the Renaissance and beyond. The founding of the Accademia del Disegno, which Vasari championed, set a precedent for art education across Europe, promoting the idea that art required theoretical knowledge as well as practical skill. The Lives itself served as a form of textbook, disseminating knowledge about techniques, styles, and artistic lineages.

Furthermore, the book's engaging narrative style made it accessible beyond a narrow circle of connoisseurs. It brought the artists of the Renaissance to life, portraying them as complex individuals driven by ambition, rivalry, piety, and genius. This humanizing approach helped foster a wider appreciation for art and its creators. Even today, while scholars approach Vasari critically, cross-referencing his accounts with archival documents and other sources, the Lives remains an essential starting point and a treasure trove of information and insight into the world of Renaissance Italy.

Critiques and Historical Context of The Lives

While celebrating the monumental achievement of Vasari's Lives, it is crucial to acknowledge its limitations and the criticisms leveled against it, both by his contemporaries and later scholars. Understanding these critiques helps place the work within its proper historical context and use it more effectively as a source.

The most significant criticism concerns Vasari's pronounced Tuscan, and specifically Florentine, bias. He consistently championed artists from Florence, often at the expense of those from other important artistic centers like Venice, Siena, Padua, or Lombardy. Venetian masters like Titian, while included (especially in the second edition after Vasari visited Venice), are sometimes assessed according to Florentine standards of disegno, potentially undervaluing their mastery of color (colorito). Artists from earlier periods or rival schools could be treated dismissively or inaccurately.

Factual errors and chronological inconsistencies are also present throughout the Lives. Vasari sometimes relied on oral tradition, anecdotes, or incomplete information, leading to mistakes in dates, attributions, or descriptions of events. Modern archival research has corrected many of these inaccuracies, revealing instances where Vasari embellished stories or misinterpreted evidence to fit his narrative framework.

His personal relationships also influenced his judgments. His profound admiration for Michelangelo led to an almost hagiographic portrayal, while artists he disliked or competed with, such as Baccio Bandinelli, often received harsh treatment. His account of the Sienese painter Sodoma, for example, is notoriously negative. There were also accusations, even in his own time, that he incorporated gossip or malicious rumors, as potentially seen in his comments about Francesco Salviati within the biography of another artist (possibly Tintoretto, referred to ambiguously in some sources).

However, these criticisms should be understood within the context of the 16th century. The concept of objective historical writing was still developing, and local pride (known as campanilismo) was intense. Vasari was writing relatively soon after the events he described, without the benefit of modern research methods. His primary goal was arguably not just historical accuracy but also the promotion of Florentine artistic supremacy and the celebration of art itself, particularly as embodied by Michelangelo and supported by his Medici patrons. Recognizing these biases allows historians to use the Lives critically, valuing its unique insights while corroborating its claims with other evidence.

A Network of Relationships: Patrons and Peers

Giorgio Vasari navigated a complex web of relationships throughout his career, interacting with powerful patrons, influential mentors, collaborators, and rivals. These connections were crucial to his success as both an artist and a chronicler of the art world.

His most important patronage relationship was with the Medici family, particularly Duke Cosimo I de' Medici. Vasari served as a court artist and architect for Cosimo, undertaking major projects like the Uffizi, the Vasari Corridor, and the decoration of the Palazzo Vecchio. This close tie provided him with financial stability, prestigious commissions, and access to the highest levels of Florentine society. His loyalty to the Medici is evident in his work and writings, which often celebrate the dynasty.

Among artists, his relationship with Michelangelo was paramount. Vasari revered the older master, sought his advice, and dedicated a significant portion of the Lives to him, portraying him as the culmination of artistic evolution. While Michelangelo was undoubtedly the dominant figure, their interactions suggest a degree of mutual respect, with Vasari acting as a conduit for information and commissions in Michelangelo's later years.

His early training under Andrea del Sarto established a foundational relationship. Vasari clearly admired his teacher's skill, and his biography of del Sarto in the Lives is detailed and largely sympathetic, though perhaps tinged with a hint of criticism regarding del Sarto's perceived lack of ambition compared to giants like Michelangelo.

With Francesco Salviati, the relationship appears to have been one of close friendship and collaboration early on, studying together in Rome. However, later accounts, including Vasari's own writings as interpreted by critics, suggest potential rivalry or jealousy, possibly stemming from competition for commissions or status within the Medici court.

His interactions with other leading figures varied. He collaborated with Rosso Fiorentino, another key Mannerist painter who later worked at Fontainebleau in France. Vasari expressed clear disdain for the sculptor Baccio Bandinelli, a rival of Michelangelo whom Vasari criticized sharply in the Lives. He had professional contact with Venetian artists like Sebastiano del Piombo and Titian, acknowledging their importance but assessing them through his Florentine lens.

Vasari's Lives itself documents countless other relationships, both direct and indirect. He studied the works of Leonardo da Vinci and Raphael intensely, placing them alongside Michelangelo at the apex of the High Renaissance, though often setting up a comparison, particularly between the perceived divine grace of Raphael and the awesome power (terribilità) of Michelangelo. He wrote extensively about foundational figures like Giotto and Cimabue, and artists whose work he encountered, like Pontormo or Tintoretto (whose work he saw in Venice). This network highlights Vasari's central position within the Italian Renaissance art world, both participating in it and documenting it.

Vasari's Artistic Style in Perspective

Giorgio Vasari's own artistic style as a painter and architect is best understood as a prominent example of Central Italian Mannerism. Flourishing in the period between the High Renaissance (c. 1520) and the emergence of the Baroque (c. 1600), Mannerism was a style characterized by sophistication, artificiality, and a self-conscious display of skill (maniera). Vasari's work embodies many of its key features.

In his paintings, Vasari favored complex, often crowded compositions with numerous figures arranged in intricate, sometimes deliberately unnatural poses. Elongated limbs, serpentine postures (figura serpentinata), and foreshortening were employed to demonstrate technical virtuosity. His color palettes tended towards vibrant, sometimes acidic or discordant hues, moving away from the balanced naturalism of the High Renaissance towards more decorative and expressive effects. Clarity of narrative remained important, especially in his large historical and allegorical cycles for the Medici, but it was often conveyed through elaborate symbolism and dynamic, theatrical arrangements.

His architectural work similarly reflects Mannerist tendencies. While utilizing the classical vocabulary of orders, columns, and pediments derived from antiquity and the High Renaissance, Vasari often employed these elements in novel or complex ways. The extended facade of the Uffizi, with its rhythmic repetition and controlled elegance, demonstrates a Mannerist concern for order and grace on a grand scale. The Vasari Corridor, a feat of adaptive engineering, prioritized function and ducal prestige over purely aesthetic concerns in its external appearance, yet its conception reflects the period's taste for ingenious solutions and displays of power.

Underlying both his painting and architecture was the principle of disegno, which Vasari championed in his writings. His works emphasize clarity of line, careful planning, and intellectual conception. He saw art as an intellectual pursuit requiring knowledge of perspective, anatomy, history, and allegory. His own facility and speed of execution, while sometimes leading to accusations of superficiality, were also seen as demonstrations of his mastery over disegno and his inventive capacity. While perhaps not reaching the sublime heights of his idol Michelangelo, Vasari was a highly competent, versatile, and influential artist whose work perfectly captured the sophisticated, courtly aesthetic of mid-16th-century Florence.

Legacy and Conclusion: The Indispensable Vasari

Giorgio Vasari's legacy is multifaceted, but his role as the "father of art history" remains his most significant contribution. Through his Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects, he provided not only a priceless repository of information about hundreds of Italian Renaissance artists and their works but also the very framework through which the art of that period would be understood for centuries. He established a canon, created a narrative of artistic development, and championed the intellectual status of the artist, profoundly shaping Western art historical thought.

As an artist and architect, Vasari was a leading figure of Florentine Mannerism. His paintings, particularly the extensive fresco cycles in the Palazzo Vecchio, exemplify the elegant, complex, and courtly style favored by his Medici patrons. His architectural achievements, most notably the Uffizi Palace and the Vasari Corridor, fundamentally altered the urban fabric of Florence and remain iconic landmarks. His work consistently demonstrated technical skill, intellectual rigor based on the principle of disegno, and an ability to manage large-scale, complex projects.

His role in founding the Accademia del Disegno in Florence marked a crucial step in the formalization of art education, setting a precedent for academies across Europe. He was a man deeply embedded in the artistic and political life of his time, a skilled networker who navigated the complex world of patronage and artistic rivalry.

While modern scholarship approaches his writings critically, aware of his biases and inaccuracies, the Lives remains an indispensable primary source. It offers unparalleled insight into the techniques, personalities, and social context of Renaissance art. Vasari's vivid narratives continue to bring the artists of the era to life. Ultimately, Giorgio Vasari was more than just a painter, architect, or writer; he was a synthesizer, an organizer, and a promoter of the arts. His work, both written and visual, played a crucial role in defining the Italian Renaissance and ensuring its enduring legacy. He remains a central figure for anyone seeking to understand the art and culture of that extraordinary period.