Giovan Battista Naldini stands as a significant figure in the landscape of 16th-century Italian art, particularly within the vibrant artistic milieu of Florence. Active during the later phase of the Renaissance, a period often characterized by the stylistic complexities of Mannerism, Naldini carved out a distinct career as a painter and draftsman. His life and work offer a fascinating window into the artistic currents, patronage systems, and collaborative workshop practices that defined this era of profound cultural transformation.

Born in the picturesque town of Fiesole, overlooking Florence, around 1537, Naldini's artistic journey began at a young age. He died in Florence on February 18, 1591, leaving behind a substantial body of work that continues to be studied and appreciated for its technical skill and emotive power. His oeuvre primarily consists of religious altarpieces, frescoes, and cabinet pictures, alongside a prolific output of drawings that reveal his meticulous working process and his deep engagement with the human form.

Early Training and the Enduring Influence of Pontormo

The formative years of any artist are crucial, and for Naldini, this period was defined by his apprenticeship under one of the leading exponents of early Florentine Mannerism, Jacopo Carucci, universally known as Pontormo. Around the age of twelve, circa 1549, Naldini entered Pontormo's workshop. This was not a fleeting association; he remained with the master for an extended period, reportedly for up to twelve years, until Pontormo's death in 1557.

Pontormo, a student of Andrea del Sarto, was an artist of profound originality and psychological depth. His style was characterized by elongated figures, unsettling spatial constructions, vibrant and often unconventional color palettes, and a palpable sense of spiritual intensity or unease. Working in such close proximity to a master of this caliber undoubtedly left an indelible mark on the young Naldini. He would have absorbed Pontormo's distinctive approach to figure drawing, his complex compositional strategies, and his emotive use of color and light.

The workshop environment under Pontormo would have been rigorous. Apprentices like Naldini would have started with menial tasks, gradually progressing to grinding pigments, preparing panels and canvases, transferring cartoons, and eventually painting less critical passages in the master's works. This hands-on training provided a thorough grounding in the technical aspects of painting and drawing, which was the bedrock of Florentine artistic practice, encapsulated in the concept of disegno – the intellectual and practical ability to conceive and execute a design through drawing.

Even after Pontormo's passing, the influence of his style remained a consistent thread in Naldini's work. The elongated proportions of his figures, a certain nervous energy in their gestures, and a tendency towards expressive, sometimes melancholic, countenances can often be traced back to his master's example. However, Naldini was not a mere imitator; he would go on to assimilate other influences and forge his own distinct artistic identity.

Roman Sojourn and Broadening Artistic Horizons

Following Pontormo's death, Naldini sought to broaden his artistic experience. Like many aspiring artists of his generation, he traveled to Rome, the epicenter of the High Renaissance and a city teeming with ancient and contemporary artistic marvels. He is documented in Rome between 1560 and 1561. This period was crucial for his development, exposing him to a wider range of artistic stimuli beyond the predominantly Florentine influences he had hitherto absorbed.

In Rome, Naldini would have encountered firsthand the monumental works of High Renaissance masters such as Raphael and Michelangelo. Raphael's Stanze in the Vatican, with their harmonious compositions and idealized figures, offered a powerful counterpoint to Pontormo's more idiosyncratic style. Michelangelo's Sistine Chapel ceiling and his later works, like the Last Judgment, provided awe-inspiring examples of anatomical mastery and dramatic power. Naldini, like many of his contemporaries, diligently studied and drew from these masterpieces, as well as from classical statuary.

The source material also suggests an influence from Polidoro da Caravaggio, a student of Raphael known for his dynamic, often monochromatic, friezes all'antica (in the ancient style) that adorned the facades of Roman palaces. Polidoro's energetic figures and narrative clarity may have appealed to Naldini. This Roman experience likely tempered some of the more extreme aspects of Pontormo's Mannerism in Naldini's art, leading to a greater sense of structure and, at times, a more classical poise in his figures, though the expressive intensity learned from his first master was never fully abandoned.

Collaboration with Giorgio Vasari: A Defining Partnership

Upon his return to Florence, Naldini entered a new and highly significant phase of his career: a close association with Giorgio Vasari. Vasari was not only a prolific painter and architect but also the influential author of Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects, a foundational text of art history. More pertinently for Naldini, Vasari was the artistic impresario for Duke Cosimo I de' Medici, overseeing vast decorative projects that transformed the civic and palatial spaces of Florence.

Naldini became one of Vasari's most trusted and active collaborators, contributing to several large-scale commissions. This partnership required Naldini to adapt his style to some extent to conform to Vasari's overall vision and the programmatic requirements of these ducal projects. Vasari's own style was a more academic and courtly form of Mannerism, often geared towards clear legibility and the glorification of the Medici dynasty.

One of the most extensive projects was the redecoration of the Palazzo Vecchio, Florence's town hall, which Cosimo I had transformed into his ducal residence. Naldini worked alongside a team of artists under Vasari's direction, painting frescoes and panel paintings for various apartments, including the Quartiere degli Elementi and the Quartiere di Leone X. His contributions, while integrated into Vasari's grand scheme, often retain a personal touch in the fluidity of the figures and the richness of color.

A particularly prestigious commission within the Palazzo Vecchio was the Studiolo of Francesco I, a small, lavishly decorated private study and cabinet of curiosities for Cosimo's son and heir, created between 1570 and 1575. This intimate space was adorned with allegorical paintings by a select group of Florence's leading artists, each illustrating themes related to nature and human ingenuity. Naldini contributed two panels: the Allegory of Dreams and the Collection of Ambergris. The Studiolo project involved a constellation of talented painters, including Alessandro Allori, Mirabello Cavalori, Maso da San Friano, Giovanni Stradano (Jan van der Straet), Santi di Tito, and Francesco Morandini (known as Il Poppi), all working under the intellectual guidance of Vincenzo Borghini and Vasari.

Naldini also played a role in the ephemeral decorations for the funeral of Michelangelo in 1564, an event orchestrated by Vasari to honor the great master. This participation further cemented Naldini's position within the Florentine artistic establishment. His ability to work effectively within a large workshop, meet deadlines, and adapt to complex iconographic programs made him an invaluable asset to Vasari.

The Accademia del Disegno: A Commitment to Artistic Education

Beyond his collaborations on specific commissions, Naldini was involved in a foundational initiative that would shape the future of art education in Europe: the Accademia del Disegno (Academy of Drawing). Established in Florence in 1563 under the patronage of Duke Cosimo I, with Vasari and the humanist Vincenzo Borghini as key instigators, the Accademia was the first formal institution of its kind dedicated to the training of artists and the elevation of their social status.

The Accademia aimed to move artistic training beyond the traditional workshop system, providing a more structured and theoretical education. It emphasized disegno – drawing and design – as the fundamental principle underlying painting, sculpture, and architecture. Naldini was among the founding members of this prestigious institution, a testament to his standing in the Florentine artistic community. His involvement underscores his commitment to the principles of Florentine art and his engagement with the intellectual currents of his time. The Accademia brought together established masters like Agnolo Bronzino, Francesco da Sangallo, Benvenuto Cellini, and Bartolomeo Ammannati, alongside younger talents, fostering a vibrant environment for artistic exchange and learning.

Mature Style and Major Religious Commissions

While Naldini's work for the Medici court under Vasari was significant, a substantial portion of his oeuvre consists of religious paintings, primarily altarpieces and frescoes for churches in Florence and other Tuscan towns, as well as in Rome. In these commissions, Naldini often had more freedom to express his personal style, which matured into a sophisticated blend of Pontormo's expressive intensity, Vasari's compositional clarity, and the lessons learned from Roman High Renaissance art.

His figures typically exhibit the elongated proportions characteristic of Mannerism, but they are often imbued with a graceful fluidity and a sense of emotional depth. His compositions are complex, with figures arranged in dynamic, sometimes swirling, patterns. Naldini was a skilled colorist, employing a rich palette that could range from vibrant, almost acidic hues reminiscent of Pontormo, to more somber and harmonious tones.

One of his most notable religious commissions was for the Basilica di Santa Croce in Florence. For the tomb of Michelangelo, designed by Vasari, Naldini painted one of the allegorical figures of Painting, and more significantly, the altarpiece for the Buonarroti altar, the Pietà e angeli reggicortina (Lamentation with Angels Holding a Curtain), completed around 1578. This poignant work depicts the dead Christ supported by angels, with the Virgin Mary and other figures in mourning, set against a dramatic curtain. It showcases Naldini's ability to convey profound religious emotion with elegance and technical finesse. He also contributed other works to Santa Croce, including an Entry of Christ into Jerusalem and a Deposition.

Naldini also executed important works for the Basilica di Santa Maria Novella. For the Cappella Gaddi, he painted an Adoration of the Shepherds and a Presentation in the Temple. These altarpieces demonstrate his mastery of large-scale narrative composition and his ability to integrate figures harmoniously within an architectural setting. Other Florentine churches that house his works include San Marco, Santo Spirito, and Santa Trinita. His reputation extended beyond Florence; he undertook commissions in Rome, including frescoes depicting scenes from the life of St. John the Baptist for the church of San Giovanni Decollato.

Analysis of Key Works

Several works stand out in Naldini's oeuvre, exemplifying his artistic strengths and stylistic characteristics.

The Pietà e angeli reggicortina in Santa Croce is a prime example of his mature religious art. The composition is carefully balanced, with the diagonal thrust of Christ's body creating a focal point. The grief of the Virgin is palpable yet restrained, adhering to contemporary ideals of decorum. The angels, with their elegant forms and sorrowful expressions, add to the pathos of the scene. The rich colors and the dramatic play of light and shadow enhance the emotional impact.

Another recurring theme in Naldini's work is the Lamentation over the Dead Christ. Several versions exist, attesting to the demand for this devotional subject. These paintings typically feature a group of mourners – the Virgin Mary, Mary Magdalene, St. John the Evangelist – gathered around the body of Christ. Naldini excels in depicting the varied emotional responses of the figures, from quiet sorrow to more overt expressions of grief. His skill in rendering anatomy and drapery is evident in these works.

The Raising of the Son of the Widow of Naim, a subject Naldini painted for the Salviati Chapel in San Marco, Florence (though some sources place it elsewhere), showcases his ability to handle complex multi-figure compositions with narrative clarity. The scene, described in the Gospel of Luke, is one of Christ's miracles. Naldini captures the drama of the moment, contrasting the astonishment of the onlookers with the solemn power of Christ and the dawning life in the resurrected youth.

His Christ Carrying the Cross, now in the Museo Nacional del Prado in Madrid, is a powerful and dynamic composition. Christ, burdened by the heavy cross, stumbles forward, his face etched with suffering. The figures around him – Roman soldiers, jeering crowds, grieving followers – create a sense of turmoil and urgency. Naldini uses strong diagonals and a compressed pictorial space to heighten the dramatic tension. The colors are rich and somber, contributing to the painting's tragic mood.

The Importance of Drawing in Naldini's Practice

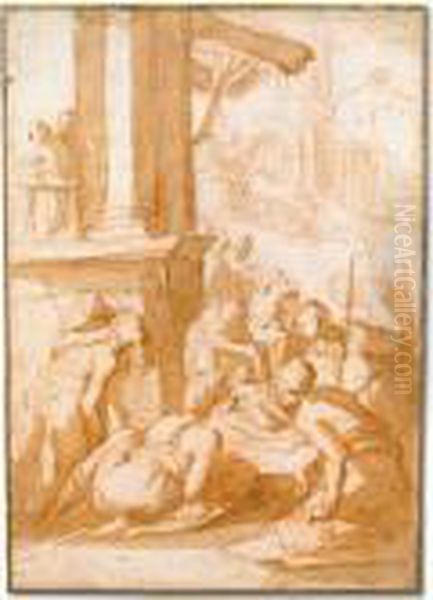

Like most Florentine artists of his era, Naldini was a prolific draftsman. Drawing, or disegno, was considered the foundation of all the visual arts, a means of exploring ideas, studying anatomy, and perfecting compositions before committing them to paint. A significant number of Naldini's drawings have survived, executed primarily in red or black chalk, often heightened with white.

These drawings offer invaluable insights into his creative process. They range from quick compositional sketches and studies of individual figures or limbs to more finished preparatory drawings for specific paintings. His figure studies reveal a keen observational skill and a thorough understanding of human anatomy, often characterized by the same elongated elegance found in his paintings. He frequently drew from live models, a standard practice in Florentine workshops.

Naldini also made copies of works by other masters, a common method of study. His drawings after Michelangelo's sculptures, such as those for the Medici Chapel or the Rape of Ganymede, demonstrate his engagement with the art of the great master and his efforts to absorb lessons in anatomical power and dynamic movement. These drawings were not mere exercises; they were part of a continuous process of learning and refinement that informed his painted works. Many of Naldini's drawings are prized by collectors and museums today for their intrinsic beauty and their art-historical significance.

Later Years, Legacy, and Art Historical Standing

Giovan Battista Naldini remained an active and respected artist in Florence throughout his career. He continued to receive commissions for altarpieces and other paintings until his death in 1591. He also took on students, passing on his knowledge and skills to the next generation of artists. One of his notable pupils was Cosimo Daddi, who continued to work in a style indebted to his master.

Naldini's legacy is that of a highly accomplished painter and draftsman who made significant contributions to the Florentine artistic scene of the late 16th century. He successfully navigated the complex artistic currents of his time, synthesizing the influences of his master Pontormo, his collaborator Vasari, and the broader traditions of the High Renaissance. While he may not have possessed the revolutionary originality of Pontormo or Rosso Fiorentino, or the overarching influence of Vasari, Naldini was a master of his craft, capable of producing works of great elegance, emotional depth, and technical skill.

His art represents a distinctive strand of late Florentine Mannerism, characterized by a refined sensibility, a sophisticated use of color, and a particular talent for conveying human emotion. He stands as a bridge figure, in some ways, between the high Mannerism of Pontormo and Bronzino and the more reformist tendencies that began to emerge in Florentine art towards the end of the 16th century with artists like Santi di Tito or Ludovico Cigoli, who sought a greater naturalism and clarity in their work, partly in response to the Counter-Reformation.

In the broader context of Italian art, Naldini's contemporaries included figures like Federico Zuccari and Taddeo Zuccari in Rome, and in Venice, masters like Tintoretto and Veronese were developing their own dramatic and color-driven styles. Naldini's work, firmly rooted in the Florentine tradition of disegno, offers a contrast to these other regional schools, highlighting the rich diversity of artistic expression in Renaissance Italy.

Today, Giovan Battista Naldini is recognized as an important artist of his generation. His paintings and drawings are found in major museums and collections around the world, and he continues to be the subject of scholarly research. His career exemplifies the life of a successful professional artist in 16th-century Florence, deeply engaged with the artistic, religious, and civic life of his city, and leaving behind a legacy of beautiful and compelling works of art.