Hendrick Bloemaert (c. 1601/1602 – 1672) stands as a significant figure in the rich tapestry of the Dutch Golden Age of painting. Born and primarily active in Utrecht, he was an artist whose career witnessed and absorbed the major stylistic currents of his time, moving from the lingering elegance of Mannerism through the dramatic intensity of Caravaggism to the balanced harmony of Classicism. As the eldest son of the highly influential painter and teacher Abraham Bloemaert, Hendrick inherited a formidable artistic legacy, yet he forged his own path, contributing distinctively to the vibrant artistic milieu of Utrecht, a city unique in the Dutch Republic for its strong Catholic presence and its direct artistic links to Italy.

Hendrick Bloemaert was not merely a painter; he was also an accomplished poet and possibly engaged in printmaking, reflecting the versatile talents often found in artists of this era. His oeuvre encompasses a range of subjects, including historical and biblical narratives, mythological scenes, portraits, and genre pieces, often imbued with a thoughtful, sometimes subtly moralizing tone. Understanding Hendrick Bloemaert requires appreciating his position within a prominent artistic family, his engagement with international artistic trends, and his individual contribution to the Utrecht School.

The Bloemaert Artistic Dynasty

The name Bloemaert was synonymous with art in Utrecht for generations. Hendrick's father, Abraham Bloemaert (1566–1651), was a towering figure whose exceptionally long and productive career spanned the transition from late Mannerism to the Baroque. Abraham was not only a prolific painter but also a renowned teacher and a skilled designer of prints. His workshop was a crucial training ground for numerous artists, making him arguably the most important artistic educator in Utrecht during the early 17th century. His influence extended far beyond his direct pupils, shaping the artistic landscape of the city.

Hendrick grew up immersed in this artistic environment. He received his primary training from his father, absorbing the fundamentals of drawing, composition, and painting technique. Abraham's own style evolved significantly over his lifetime, initially rooted in the elegant, somewhat artificial conventions of Haarlem Mannerism, characterized by elongated figures, complex poses, and vibrant, sometimes acidic colours. Later, Abraham adeptly incorporated elements of the burgeoning Baroque naturalism and the dramatic lighting inspired by Caravaggio, without ever fully abandoning a certain decorative grace.

This paternal influence was profound and lasting for Hendrick. He shared the workshop with his brothers, several of whom also became artists: Cornelis Bloemaert II (c. 1603–c. 1692) became a highly respected engraver, particularly known for reproducing works by his father and other Italian and Dutch masters; Adriaen Bloemaert (c. 1609–1666) was a painter of landscapes and animal scenes; and Frederick Bloemaert (c. 1614/17–1690) was primarily an engraver, famous for his drawing instruction book based on his father's designs. This familial context provided both support and a standard of excellence for Hendrick to measure himself against.

Early Career and Lingering Mannerism

Hendrick's earliest works naturally reflect the style prevalent in his father's studio during his formative years. This would have included elements of the late Mannerist aesthetic that Abraham Bloemaert had helped introduce to Utrecht. Characteristics of this style include a preference for sophisticated, often intricate compositions, figures depicted in elegant, sometimes contorted poses (the figura serpentinata), and a bright, decorative colour palette. Subjects often drew from mythology or allegory, treated with a sense of refinement and artificiality.

While specific, securely dated works from Hendrick's earliest independent period can be challenging to pinpoint, the foundational techniques and stylistic inclinations absorbed from his father are evident. Some early works, when rediscovered, have occasionally been confused with those of other artists or even his father, highlighting the strong initial connection. For instance, a painting depicting Joseph in Egypt, rediscovered in the 20th century, was initially attributed elsewhere before being recognized as an early Hendrick Bloemaert, showcasing his developing skill within the established family tradition.

The Shadow of Caravaggio: Utrecht Caravaggism

The most defining stylistic shift in Utrecht painting during Hendrick Bloemaert's youth was the arrival of Caravaggism. Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio (1571–1610) had revolutionized painting in Rome with his dramatic use of chiaroscuro (strong contrasts between light and dark, often termed tenebrism), his unflinching naturalism depicting religious and mythological figures in contemporary guise, and his focus on moments of intense psychological drama. His impact was immediate and widespread.

Utrecht became the primary conduit for Caravaggio's influence into the Northern Netherlands. Unlike the predominantly Protestant cities like Amsterdam or Haarlem, Utrecht retained a significant Catholic population and maintained closer ties with Rome. Several young Utrecht artists travelled to Italy in the 1610s and early 1620s, experiencing Caravaggio's work firsthand (or that of his immediate followers like Bartolomeo Manfredi). Key figures among these returning artists were Gerard van Honthorst (1592–1656), Hendrick ter Brugghen (1588–1629), and Dirck van Baburen (c. 1595–1624).

Upon their return to Utrecht around 1620, these painters brought the Caravaggesque style back with them, adapting it to local tastes. They became known as the Utrecht Caravaggisti. Their work often featured nocturnal scenes illuminated by artificial light sources (a specialty of Honthorst, earning him the Italian nickname "Gherardo delle Notti"), half-length figures of musicians, drinkers, or fortune tellers pushed close to the picture plane, and religious scenes rendered with a powerful, sometimes gritty realism. Abraham Bloemaert himself responded to this new wave, incorporating stronger light effects and more robust figures into his own work, though often softening the raw drama associated with Caravaggio.

Hendrick's Engagement with Caravaggism

Hendrick Bloemaert, working alongside his father and witnessing the success of Honthorst, Ter Brugghen, and Baburen, inevitably absorbed the Caravaggesque idiom. While it's debated whether Hendrick travelled to Italy himself (evidence is scarce and inconclusive), he was certainly exposed to the style directly through the works of the returned Utrecht painters and through his father's interpretations. His paintings from the 1620s and 1630s clearly show this influence.

He adopted the strong contrasts of light and shadow, using directed light to model forms, create volume, and enhance the dramatic impact of his scenes. Figures often emerge from dark backgrounds, their features and textures highlighted by a focused illumination. However, Hendrick's interpretation of Caravaggism often appears somewhat moderated compared to the starker tenebrism of Honthorst or the sometimes melancholic realism of Ter Brugghen. His lighting could be softer, the transitions smoother, and his colour palette often remained richer and more varied than the predominantly earthy tones favoured by some Caravaggisti. This nuanced approach, perhaps reflecting his father's influence, led to what some have described as a characteristic "Bloemaert effect" – a blend of Caravaggesque drama with a certain refinement and attention to colouristic harmony.

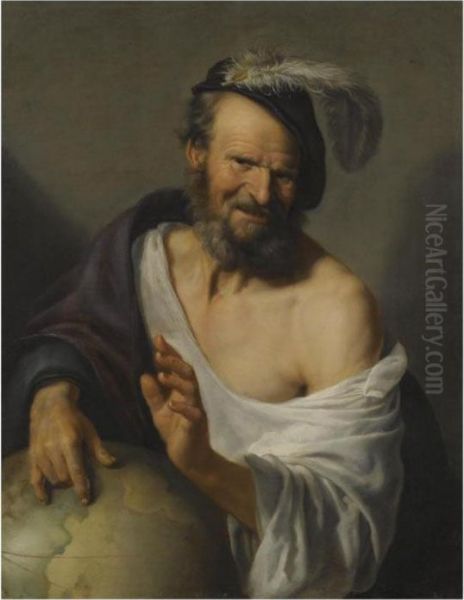

His subjects during this period often aligned with those popular among the Utrecht Caravaggisti: single figures of musicians, drinkers, or allegorical representations, as well as religious narratives treated with a new sense of immediacy and realism. He depicted wrinkled skin, coarse fabrics, and expressive physiognomies with convincing detail, bringing sacred and historical figures to life in a relatable, human manner.

Diverse Themes and Subjects

Throughout his career, Hendrick Bloemaert addressed a wide array of subjects, demonstrating versatility and adapting his style to the theme at hand.

Religious Narratives: Biblical stories formed a significant part of his output. Utrecht's Catholic patronage provided a market for religious art that was less prevalent in other Dutch cities after the Reformation. Bloemaert painted scenes from both the Old and New Testaments. Works like Moses Striking the Rock showcase his ability to handle complex multi-figure compositions, filled with dynamic action and expressive detail, often set against dramatic landscapes or architectural backdrops. The lighting in such works typically serves to focus attention on the main protagonists and the miraculous event.

Another example, The Expulsion of Hagar and Ishmael, treats a poignant Old Testament story with sensitivity, capturing the emotional distress of the figures through gesture and expression, set within a carefully rendered landscape that contributes to the mood. His depiction of Lot and His Daughters, a theme popular in the period, allowed for the exploration of complex human emotions and moral ambiguity, often rendered with the heightened realism and dramatic lighting characteristic of his Caravaggesque phase. A collaborative work with his father, a small grisaille of St. John Preaching, demonstrates the close working relationship and shared stylistic interests within the family.

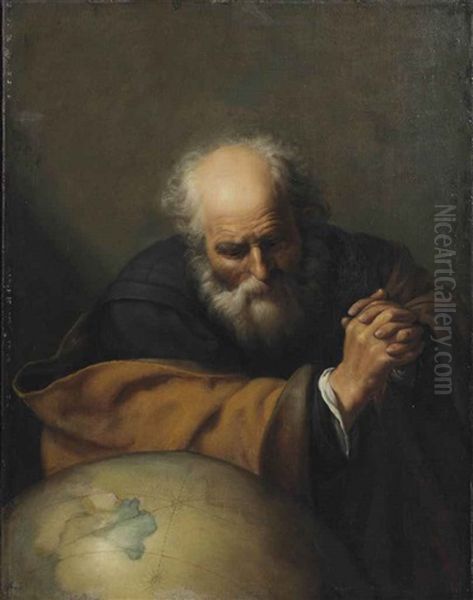

Mythological and Allegorical Scenes: Following the tradition established by his father, Hendrick also painted mythological and allegorical subjects. These often drew upon classical literature or contemporary emblems and ideas. Granida and Daifilo, based on a popular pastoral play by the Dutch writer P.C. Hooft (1581–1647), exemplifies this genre. Such works allowed for the depiction of idealized figures, often in pastoral settings, exploring themes of love, virtue, and fidelity, frequently rendered with an elegance that might foreshadow his later move towards Classicism. Allegorical figures, representing concepts like the Five Senses or philosophical ideas (e.g., his depictions of Heraclitus and Democritus), were also part of his repertoire, often presented as compelling character studies.

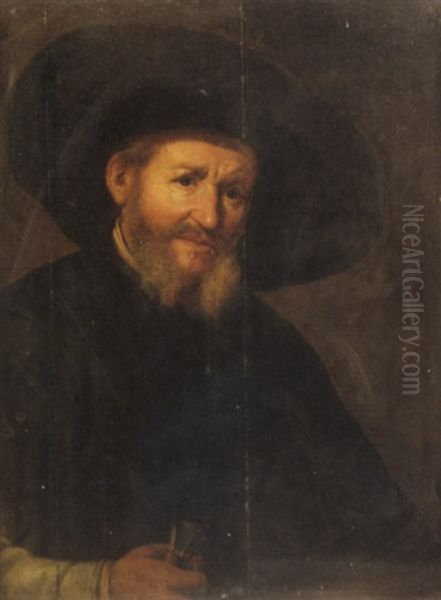

Portraiture: Hendrick Bloemaert was also active as a portrait painter, although perhaps less prolifically than specialists in the genre. His portraits, including potential self-portraits, demonstrate a capacity for capturing a sitter's likeness with honesty and psychological insight. He employed his skill in rendering textures – fabrics, hair, skin – and used lighting effectively to model the face and convey presence. These portraits provide valuable records of Utrecht citizens and reflect the broader Dutch interest in realistic representation of individuals.

Genre Painting: While perhaps less central to his oeuvre than history painting, Hendrick did engage with genre themes, particularly single figures characteristic of the Utrecht Caravaggisti – musicians playing lutes or violins, drinkers, or figures embodying specific character types. These works often combine realistic observation with a degree of idealization or allegorical intent.

Analysis of Representative Works

Several key works illustrate Hendrick Bloemaert's style and thematic concerns:

Moses Striking the Rock (c. 1640s, e.g., version in Metropolitan Museum of Art): This painting exemplifies Bloemaert's ability to manage a large-scale historical narrative. The composition is crowded yet legible, focusing on the central figure of Moses performing the miracle. Figures react with varied expressions of thirst, awe, and relief. The lighting is dramatic, highlighting Moses and the gushing water, while casting parts of the crowd and the rocky landscape into shadow. The colours are relatively rich and varied, demonstrating a step away from the more limited palettes of some Caravaggisti. The work combines biblical storytelling with keen observation of human behaviour and a dynamic composition.

The Expulsion of Hagar and Ishmael (e.g., version dated 1635): This work captures a moment of intense emotion. Abraham's stern gesture, Hagar's tearful face, and Ishmael's bewildered look are rendered with empathy. The figures are solid and realistically depicted, influenced by Caravaggism, but the overall lighting might be softer, more atmospheric than starkly tenebrist. The inclusion of a detailed landscape background adds depth and context, typical of the Bloemaert family's interest in integrating figures and settings. The careful rendering of fabrics and details showcases Hendrick's technical skill.

Granida and Daifilo (1634, Private Collection): This painting illustrates a popular theme from Dutch literature. It depicts the Persian princess Granida and the shepherd Daifilo in a pastoral setting. The style here might show a move towards greater elegance and refinement compared to his more robust Caravaggesque works. The lighting is likely softer, the colours potentially brighter and more decorative, and the figures rendered with a certain idealized grace suitable for the romantic theme. It reflects the artist's engagement with contemporary culture beyond purely religious or classical subjects.

Portrait of a Man (various examples, e.g., Centraal Museum, Utrecht): His portraits typically present the sitter in a three-quarter view, often against a neutral dark background, focusing attention on the face and costume. The lighting models the features clearly, revealing character through subtle expression and gaze. Attention is paid to rendering the textures of clothing, lace collars, and hair, reflecting the Dutch preoccupation with material realism and status.

The Shift Towards Classicism

From the 1640s onwards, Dutch painting in general began to move away from the dramatic intensity of the High Baroque and Caravaggism towards a more classical aesthetic. This trend, influenced partly by French Classicism and contemporary Italian painting (particularly the Bolognese school represented by artists like Guido Reni and Domenichino), favoured clarity, balance, harmony, and restraint. Compositions became more ordered, lighting clearer and more evenly distributed, colours often cooler and smoother, and emotional expression more subdued and idealized.

Hendrick Bloemaert's later works reflect this shift. While he never completely abandoned the lessons learned from Caravaggism, his style evolved towards greater elegance and calmness. The dramatic chiaroscuro often softened into a clearer, more diffused light. Compositions became more balanced and stable, sometimes incorporating classical architectural elements. Figures might appear more idealized, their gestures and expressions more restrained. His colour palette could become brighter and cooler, with smoother paint application, moving away from the vigorous brushwork sometimes seen in earlier Dutch painting. This later phase shows his adaptability and his awareness of prevailing international artistic trends, ensuring his continued relevance in the changing artistic landscape of the mid-17th century.

Draughtsman and Print Designer

Like his father and brothers, Hendrick was likely active as a draughtsman. Drawings were essential for preparing compositions, studying figures, and serving as models within the workshop. While perhaps fewer drawings are securely attributed to him compared to his father, his skill in this medium would have been foundational to his painting practice.

His involvement in printmaking is less clear than that of his brothers Cornelis II and Frederick, who were specialist engravers. However, given the family's deep engagement with print production, it's plausible Hendrick designed compositions intended for engraving, or perhaps even etched plates himself. Prints were crucial for disseminating artistic ideas and compositions widely, and the Bloemaert family played a significant role in this process. Engravings after Hendrick's paintings would have helped spread his reputation beyond Utrecht. The famous drawing book compiled by Frederick Bloemaert, based on Abraham's drawings, standardized art instruction and carried the Bloemaert style far and wide, indirectly benefiting the perception of Hendrick's work as well.

Teaching, Influence, and Legacy

While Abraham Bloemaert is famed for his large number of pupils, including the major Utrecht Caravaggisti (who were more his students than Hendrick's contemporaries/colleagues in that sense), Hendrick's own role as a teacher is less documented. He likely participated in the family workshop's teaching activities, but few prominent artists are recorded specifically as his pupils. Jan van Bijlert (1597/98–1671), another Utrecht painter who blended Caravaggesque elements with a smoother, more classicizing style, had connections to the Bloemaert circle, but the exact relationship requires careful consideration.

Hendrick's influence was perhaps felt more through the consistent quality and visibility of his own work within Utrecht and beyond, and as part of the broader Bloemaert family legacy. The Bloemaerts collectively represented a dominant force in Utrecht art for nearly a century. Hendrick continued this tradition, adapting to new styles while maintaining a high level of craftsmanship. His work provided models of history painting, portraiture, and other genres that younger artists could study and respond to.

His position within the Dutch Golden Age is significant, particularly within the context of the Utrecht School. While artists like Rembrandt van Rijn (1606–1669) in Amsterdam, Frans Hals (c. 1582–1666) in Haarlem, or Johannes Vermeer (1632–1675) in Delft might command greater international fame today, Hendrick Bloemaert was a respected and successful master in his own right. His engagement with Caravaggism connects him to international Baroque trends, alongside contemporaries like the Flemish masters Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640) and Jacob Jordaens (1593–1678), whose dramatic energy also impacted Dutch art. His later move towards Classicism aligns him with Dutch artists like Caesar van Everdingen (c. 1616–1678) or Salomon de Bray (1597–1664), who pursued a more refined and idealized aesthetic.

Collections and Reception

Works by Hendrick Bloemaert are held in numerous important museum collections across the world, attesting to his historical significance and enduring appeal. These include:

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The Centraal Museum, Utrecht (which holds a significant collection of Utrecht School paintings)

The Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

The Louvre Museum, Paris

The Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg

The Detroit Institute of Arts

The Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

The Indianapolis Museum of Art

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

The National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

The Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen

The Cleveland Museum of Art

Harvard Art Museums

Musée des Beaux-Arts de Nantes

Glasgow Museums

His paintings also appear periodically on the art market, fetching respectable prices at major auction houses like Sotheby's and Christie's. The provenance history of works like his Democritus traces their journey through various private collections over the centuries, indicating a continued appreciation among collectors. The rediscovery and reattribution of works over time also contribute to the ongoing scholarly assessment of his oeuvre.

Conclusion: A Versatile Utrecht Master

Hendrick Bloemaert emerges as a talented and adaptable artist who successfully navigated the complex artistic currents of the Dutch Golden Age. Firmly rooted in the Utrecht tradition established by his father, Abraham Bloemaert, he embraced the dramatic potential of Caravaggism, contributing significantly to the distinctive character of the Utrecht School during the 1620s and 1630s. His ability to blend this Italianate drama with a Dutch sensibility for realism and often rich colour is a hallmark of his style during this period.

As artistic tastes shifted, Hendrick demonstrated his versatility by adapting to the emerging Classical trend, producing works of greater balance, clarity, and refinement in his later career. Throughout his life, he maintained a high standard of technical skill across various genres, from complex history paintings and sensitive religious scenes to insightful portraits and engaging allegories. While perhaps overshadowed historically by his highly influential father or by the more famous Dutch masters from other cities, Hendrick Bloemaert remains an important figure, representing the strength and diversity of painting in Utrecht and contributing significantly to the artistic richness of the 17th century Netherlands. His work offers a fascinating window into the interplay of local traditions and international influences that defined the Dutch Golden Age.