Giovanni Battista Beinaschi stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the vibrant tapestry of Italian Baroque art. Active during the latter half of the 17th century, his career bridged the artistic centers of Rome and Naples, absorbing and reinterpreting the dominant stylistic currents of his time. Known for his dramatic compositions, energetic brushwork, and profound use of chiaroscuro, Beinaschi carved a distinct niche for himself, particularly as a painter of large-scale frescoes and emotionally charged altarpieces. His work reflects a dynamic synthesis of influences, from the High Baroque grandeur of Giovanni Lanfranco to the intense naturalism of Caravaggio and his followers.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Giovanni Battista Beinaschi was born in Fossano, a town in the Piedmont region of Italy, in 1636. His early artistic inclinations led him to Turin, the capital of the Duchy of Savoy, where he is documented as receiving his initial training. His first master is recorded as a painter named Spirito, a figure about whom detailed historical records are somewhat scarce, suggesting he may have been a competent local artist rather than a widely celebrated master. This early instruction in Turin would have exposed Beinaschi to the prevailing artistic trends of northern Italy, which often blended local traditions with influences from both French and Roman art.

Seeking broader horizons and more advanced tutelage, Beinaschi, like many aspiring artists of his era, made his way to Rome. The Eternal City was then the undisputed center of the European art world, a crucible of innovation and a repository of classical and Renaissance masterpieces. In Rome, Beinaschi entered the workshop of Pietro del Po (1616-1692), a painter and engraver of Sicilian origin who was himself a product of the Bolognese school, having studied under Domenichino, a prominent pupil of the Carracci. Through Pietro del Po, Beinaschi would have been immersed in the classical-idealist tradition of the Carracci Academy, which emphasized drawing, anatomical correctness, and balanced composition, yet del Po was also receptive to the more dynamic and emotive aspects of the Baroque.

The Roman Period: Influences and Early Works

During his formative years in Rome, Giovanni Battista Beinaschi proved to be a keen observer and an adept student of the artistic giants who had shaped, and were continuing to shape, the city's visual landscape. The influence of Giovanni Lanfranco (1582-1647) was particularly profound on the young Beinaschi. Lanfranco, a native of Parma, had been a key figure in the development of the High Baroque style, known for his illusionistic ceiling frescoes and dynamic, emotionally charged religious scenes. His work, characterized by powerful foreshortening, swirling movement, and dramatic lighting, left an indelible mark on Beinaschi’s burgeoning style.

Another towering figure whose legacy permeated Roman art was Annibale Carracci (1560-1609). Annibale, along with his brother Agostino and cousin Ludovico, had spearheaded a reform of painting, moving away from the artificiality of Mannerism towards a renewed naturalism combined with classical ideals. His frescoes in the Farnese Gallery were a cornerstone of Baroque ceiling decoration, and his altarpieces set a standard for compositional clarity and emotional depth. Beinaschi absorbed these lessons, particularly Carracci's command of anatomy and expressive gesture.

Several of Beinaschi's works from his Roman period clearly demonstrate these influences. Paintings such as The Holy Family and The Annunciation exhibit a compositional structure and figural style that echo Lanfranco's approach. A series of paintings depicting scenes from the life of Saint Nicholas, possibly for the church of San Nicola dei Lorenesi, also shows this Lanfranchian imprint, with energetic figures and a dramatic interplay of light and shadow. These works reveal Beinaschi’s growing confidence in handling complex multi-figure compositions and his ability to convey religious narratives with conviction. He was already developing a robust, painterly technique, with visible brushstrokes contributing to the vitality of his surfaces.

The Neapolitan Chapter: Maturity and Major Commissions

In 1664, Giovanni Battista Beinaschi made a pivotal decision to relocate from Rome to Naples. This move marked the beginning of the most productive and arguably most significant phase of his career. Naples, at that time under Spanish rule, was a bustling metropolis with a fervent religious life and a strong demand for ecclesiastical art. The city had its own vibrant artistic traditions, heavily influenced by the dramatic naturalism of Caravaggio and his followers, such as Jusepe de Ribera, and later by the dynamic Baroque styles of artists like Mattia Preti and Luca Giordano.

Beinaschi quickly established himself within the Neapolitan artistic milieu, securing numerous commissions for frescoes and altarpieces in the city's many churches and religious institutions. He spent the remainder of his life in Naples, becoming one of its leading painters. His style during this period evolved, integrating the lessons learned in Rome with the more intense, tenebristic qualities favored in Naples. His palette often became darker, his chiaroscuro more pronounced, and his compositions imbued with a heightened sense of drama and pathos, aligning with the passionate spirituality of the Neapolitan context.

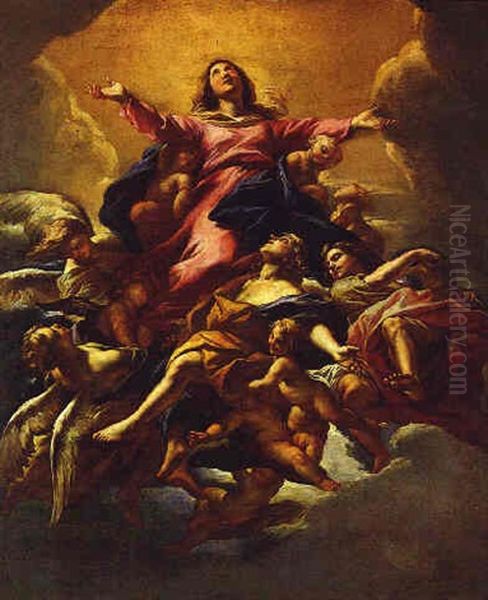

Among his most celebrated achievements in Naples are the extensive fresco decorations he undertook. He painted vast ceiling frescoes, such as the breathtaking The Paradise in the dome of the Church of Santi Apostoli. This work, a swirling vortex of figures ascending towards a divine light, showcases his mastery of illusionistic perspective and his ability to orchestrate complex celestial scenes, rivaling the achievements of Lanfranco. He also executed significant fresco cycles in other Neapolitan churches, including scenes from the life of Saint Nicholas, continuing a theme from his Roman period but now executed with a more mature and regionally inflected style. His work for the Gerolamini church and Santa Maria degli Angeli a Pizzofalcone further solidified his reputation.

Artistic Style: A Synthesis of Drama and Light

Giovanni Battista Beinaschi's artistic style is a compelling fusion of various Baroque currents, marked by a distinctive personal handling. At its core, his work is characterized by dynamism, emotional intensity, and a masterful use of light and shadow (chiaroscuro). While he absorbed the grandeur of Roman High Baroque, particularly from Lanfranco, he tempered it with a gritty realism and dramatic lighting that owed much to the Caravaggesque tradition, which had found fertile ground in Naples through artists like Jusepe de Ribera and Battistello Caracciolo.

Beinaschi's figures are often robust and muscular, rendered with energetic brushwork that imbues them with a sense of movement and vitality. His compositions are typically complex and animated, frequently employing diagonal thrusts and swirling patterns to guide the viewer's eye and enhance the narrative drama. He was particularly adept at depicting moments of spiritual ecstasy, martyrdom, or profound repentance, capturing the heightened emotional states of his subjects with convincing intensity.

A key element of his style was his sophisticated use of chiaroscuro. Light in Beinaschi's paintings is rarely uniform; instead, it is often selective and theatrical, highlighting key figures or actions while plunging other areas into deep shadow. This not only created a sense of volume and three-dimensionality but also amplified the psychological and spiritual impact of his scenes. This approach sometimes led to his work being associated with "Tenebrism," a style characterized by pronounced, often stark, contrasts of light and dark. However, unlike some more extreme Tenebrists, Beinaschi often maintained a richness in his shadows and a warmth in his illuminated areas.

Interestingly, while heavily influenced by the dramatic force of artists like Lanfranco and the Caravaggisti, some scholars note that Beinaschi, particularly in certain phases or aspects of his work, employed a somewhat softer application of color and a more blended treatment of outlines than might be expected. This suggests a nuanced approach, where he could modulate his technique to suit the specific demands of a commission or a particular expressive goal, perhaps also reflecting the influence of Venetian colorism or the sfumato of Correggio, whose dome frescoes in Parma were precursors to Lanfranco's.

Masterpieces and Notable Works

Throughout his prolific career, Giovanni Battista Beinaschi produced a substantial body of work, much of it for ecclesiastical patrons. Several paintings and fresco cycles stand out as particularly representative of his skill and artistic vision.

The Paradise fresco in the dome of the Church of Santi Apostoli in Naples is arguably one of his most ambitious and successful undertakings. This vast, illusionistic composition depicts a celestial vision of Christ in Glory surrounded by a multitude of saints and angels. The work is a tour-de-force of Baroque ceiling painting, demonstrating Beinaschi's command of foreshortening (sotto in sù) and his ability to create a sense of infinite, light-filled space opening up above the viewer. The dynamic arrangement of figures and the vibrant use of color contribute to the overwhelming sense of divine majesty.

The Repentance of Saint Peter is a theme Beinaschi returned to, and his interpretations are powerful examples of his ability to convey deep emotion. These paintings typically depict the apostle in a moment of intense grief and remorse after denying Christ, his face etched with sorrow and illuminated by a dramatic light source that emphasizes his inner turmoil. The raw emotion and strong chiaroscuro are characteristic of Beinaschi's mature Neapolitan style.

His series of paintings depicting Scenes from the Life of Saint Nicholas for various churches, both in Rome and Naples, highlight his narrative skill. These works, often part of larger decorative schemes, allowed him to explore different compositional challenges and emotional registers, from moments of miraculous intervention to acts of charity.

The altarpiece of The Annunciation, created for the Church of San Bonaventura in Naples and funded by the Genoese merchant Pellegrino Peri, is another significant work. It showcases his ability to handle traditional religious subjects with freshness and vigor, combining divine grace with human emotion.

An unfinished painting, Il Sogno di Giacobbe (Jacob's Dream), offers insight into his working process and his powerful conception of biblical narratives, even in a less complete state. The dynamic composition and expressive figures are evident, characteristic of his peak period.

The painting of Saint Paul, now in the Musée des Beaux-Arts et d'Archéologie de Besançon, is a fine example of his powerful single-figure representations, imbued with psychological depth and a strong physical presence. Similarly, Prometheus Enchained, a mythological subject, demonstrates his versatility beyond purely religious themes, capturing the agony of the Titan with characteristic Baroque drama.

Drawings and Preparatory Methods

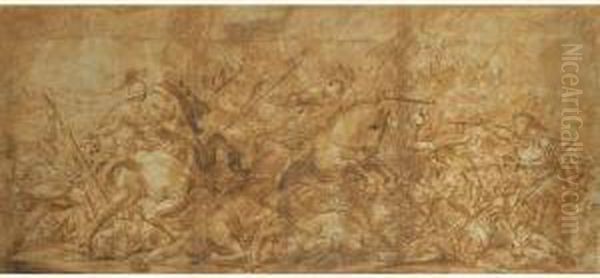

Giovanni Battista Beinaschi was a prolific draftsman, and a significant number of his drawings survive, offering invaluable insights into his creative process. The Museum Kunstpalast in Düsseldorf holds an extensive collection, estimated at around 250 drawings and design sketches, making it the most important repository of his graphic work. These drawings range from quick compositional sketches, exploring initial ideas for paintings or frescoes, to more detailed studies of individual figures, drapery, and anatomical details.

His drawings are typically characterized by their energy and fluidity. He often used pen and ink with wash, or chalk, to rapidly block out forms and establish the play of light and shadow. These preparatory works reveal his method of developing complex compositions, often experimenting with different arrangements of figures and dynamic poses. For instance, sketches for the ceiling of Santa Maria degli Angeli a Pizzofalcone show his exploration of dynamic figural arrangements suitable for viewing from below. He also produced numerous male nude studies, essential for accurately rendering the human form in his large-scale narrative scenes.

The existence of these drawings underscores the importance of disegno (drawing and design) in his practice, a foundational element of Italian artistic training. They demonstrate that his seemingly spontaneous and energetic painted surfaces were often the result of careful planning and iterative refinement. These graphic works are not mere technical exercises but are imbued with the same dynamism and expressive power found in his finished paintings.

Relationships with Contemporaries: Collaboration and Competition

The art world of 17th-century Italy was a competitive yet interconnected environment. Giovanni Battista Beinaschi navigated this landscape, forming relationships that involved both collaboration and rivalry. His training under Pietro del Po in Rome placed him within a lineage connected to Domenichino and the Carracci school. His profound admiration for Giovanni Lanfranco shaped his early development, positioning him as a follower of Lanfranco's High Baroque style.

In Rome, he is known to have collaborated with other artists on large-scale projects. For example, he worked with an assistant named Orazio Frezza on the Paradise with Christ in Glory fresco, indicating that, like many masters overseeing extensive commissions, he relied on workshop assistance.

The move to Naples brought him into a different, though equally competitive, artistic sphere. Naples was home to towering figures like Luca Giordano (1634-1705), known for his astonishing speed and prolific output, and Francesco Solimena (1657-1747), who would become a dominant force in Neapolitan painting in the later Baroque and Rococo periods. Beinaschi would have undoubtedly been aware of their work and, at times, in direct competition for prestigious commissions. For instance, records indicate he vied for a contract from the Teatini order, potentially against artists like Luigi Garzoni or even Solimena, eventually securing the project. This highlights the professional rivalries that were part and parcel of an artist's career.

His style also shows an awareness of other Neapolitan masters. The influence of Mattia Preti (1613-1699), "Il Cavalier Calabrese," known for his powerful chiaroscuro and dramatic compositions, can be discerned in Beinaschi's Neapolitan works. Similarly, the pervasive influence of Caravaggio, kept alive in Naples by artists like Jusepe de Ribera (1591-1652) and Battistello Caracciolo (1578-1635), informed Beinaschi's own approach to dramatic lighting and naturalism. While direct collaborations in Naples are less documented than his Roman period, the shared artistic environment inevitably led to an exchange of ideas and stylistic influences, even amidst competition. His work sometimes shows stylistic similarities in brushwork or light handling to artists like Scipione Compagno, suggesting a shared visual vocabulary within the Neapolitan school.

Legacy, Collections, and Enduring Presence

Giovanni Battista Beinaschi died in Naples on September 28, 1688, reportedly after a period of illness. He left behind a substantial body of work that significantly contributed to the visual culture of both Rome and, more extensively, Naples during the High Baroque period. While perhaps not achieving the household-name status of a Caravaggio or a Bernini, his artistic contributions were considerable, and his paintings were sought after for their dramatic impact and spiritual intensity.

His works are now found in numerous churches in Naples and Rome, as well as in public and private collections across Europe. As mentioned, the Museum Kunstpalast in Düsseldorf holds the most comprehensive collection of his drawings. The Musée des Beaux-Arts et d'Archéologie de Besançon in France also possesses notable works, including the aforementioned Saint Paul. Other museums, such as the British Museum and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, house examples of his drawings, attesting to the appreciation of his graphic skill.

His daughter, Angela Beinaschi, is recorded as being a painter, following in her father's footsteps. However, very little is known about her life or her artistic output, and few, if any, works are securely attributed to her, a common fate for many women artists of that era whose careers were often overshadowed or poorly documented.

Beinaschi's influence on subsequent generations of painters is not as extensively charted as that of some of his more famous contemporaries. However, his robust, painterly style and his mastery of large-scale fresco decoration undoubtedly contributed to the ongoing vitality of the Neapolitan school. His ability to synthesize Roman grandeur with Neapolitan intensity provided a powerful model for artists working in a similar vein.

Critical Reception and Art Historical Debates

Art historical assessment of Giovanni Battista Beinaschi has evolved over time. For many years, he was a figure primarily known to specialists in Italian Baroque art. However, increased scholarly attention and exhibitions have brought his work to a wider audience. He is generally recognized as a skilled and powerful painter who made significant contributions to the Baroque tradition.

Scholars praise his technical facility, his command of complex compositions, and his ability to convey profound emotion. His mastery of fresco is particularly noted, with works like The Paradise in Santi Apostoli considered high points of Neapolitan ceiling decoration. His dramatic use of chiaroscuro is seen as a key strength, linking him to the enduring legacy of Caravaggio while also reflecting the particular tastes of the Neapolitan milieu.

However, some debates and points of contention exist. The very influences that shaped him have sometimes led to criticisms of derivativeness. His clear emulation of Lanfranco, for example, while a testament to his learning, has occasionally led to his work being seen as less original than that of more radically innovative figures. Attribution has also been a challenge at times; the stylistic similarities between Beinaschi and other artists of the period, including Lanfranco himself, have sometimes led to misattributions. The spelling of his name also appears with variations in historical documents, sometimes rendered as "Bernaschi," which can add a layer of complexity to research.

Despite these debates, the prevailing view is that Beinaschi was more than a mere imitator. He absorbed diverse influences but forged them into a personal style characterized by its energy, emotional depth, and painterly vigor. His position as a key figure in the Neapolitan Seicento is now firmly established, and his works are valued for their intrinsic artistic merit and as important documents of the religious and cultural life of his time.

Conclusion: An Artist of Passion and Power

Giovanni Battista Beinaschi was a formidable talent whose career exemplifies the dynamism and artistic richness of 17th-century Italy. From his early training in Piedmont and Rome to his mature achievements in Naples, he consistently demonstrated a profound understanding of the Baroque idiom. His paintings and frescoes, characterized by dramatic compositions, energetic figures, and a masterful interplay of light and shadow, served the devotional needs of his patrons while also showcasing his considerable artistic prowess.

While navigating a world populated by artistic giants such as Bernini, Pietro da Cortona in Rome, and Luca Giordano and Mattia Preti in Naples, Beinaschi carved out a distinctive and respected position. He successfully synthesized the grand manner of Roman Baroque with the intense, often tenebrous, spirituality of Neapolitan art. His legacy endures in the numerous churches he adorned and in the collections that preserve his powerful drawings and canvases, securing his place as a significant master of the Italian Baroque.