Giovanni Battista della Rovere, often known by the diminutive "Il Fiamminghino" (the Little Fleming), was a significant Italian painter active primarily in Milan and the surrounding regions of Lombardy, Emilia, and Piedmont during the late 16th and early 17th centuries. Born in Milan around 1561 and passing away in the same city by 1630 (though some sources suggest as early as 1627), he, alongside his younger brother Giovanni Mauro della Rovere (c. 1575–1640), formed a prolific artistic partnership. Together, they were collectively referred to as "I Fiamminghi" (the Flemings), a moniker derived from their father, Riccardo, who was of Flemish origin. This familial connection to Flanders, however, primarily influenced their nickname rather than dictating a purely Northern European artistic style, as their work is deeply embedded in the Italian, specifically Milanese, artistic traditions of their time.

Early Life and Artistic Milieu

Details about Giovanni Battista's earliest years and formal training are somewhat scarce, a common reality for many artists of this period. However, it is understood that he was born into a Milan under Spanish rule, a city that was a vibrant, if complex, artistic center. The Council of Trent (1545-1563) had concluded just as he was born, and its decrees profoundly impacted religious art, steering it towards clarity, emotional directness, and doctrinal correctness. This Counter-Reformation spirit would permeate much of the artistic production in Catholic Europe, and Milan, under the influential Archbishops Charles Borromeo (later Saint Charles Borromeo) and his cousin Federico Borromeo, became a key center for implementing these artistic ideals.

It is widely accepted that Giovanni Battista, and later his brother Giovanni Mauro, received training or were significantly influenced by Camillo Procaccini (c. 1551–1629). Procaccini, himself part of an artistic dynasty from Bologna, had settled in Milan in 1587 and became a dominant figure in the local art scene. His style, characterized by a dynamic late Mannerism infused with Emilian grace and Venetian color, would have provided a crucial formative example for the young Della Rovere. The artistic environment of Milan also included figures like Simone Peterzano (c. 1535–1599), Titian's pupil and Caravaggio's first master, and Giovanni Ambrogio Figino (1548/1551–1608), a sophisticated Mannerist painter and draftsman.

The "Fiamminghi" Brothers: A Collaborative Partnership

The collaboration between Giovanni Battista and Giovanni Mauro della Rovere was a defining feature of their careers. While Giovanni Battista was the elder and likely the initial leader of their workshop, they frequently worked together on large-scale fresco cycles and altarpieces. Distinguishing their individual hands within these joint projects can often be challenging for art historians, as their styles were closely aligned. Their workshop became known for its efficiency in executing extensive decorative schemes, primarily for churches and religious confraternities, but also for private patrons.

Their collective nickname, "I Fiamminghi," underscores their shared identity in the Milanese art world. This collaborative approach was not uncommon in the period, allowing for the completion of ambitious projects that might have overwhelmed a single artist. Their output was considerable, spreading across Lombardy and into neighboring regions, testament to their reputation and the demand for their particular brand of narrative and devotional art.

Artistic Style: Late Milanese Mannerism

Giovanni Battista della Rovere's art is firmly rooted in Late Mannerism, a style that bridged the High Renaissance and the emerging Baroque. His work, and that of his brother, exhibits many characteristics of this transitional period. They were particularly influenced by the Cremonese school of Mannerism, known for its expressive intensity and complex compositions, with artists like the Campi family (Giulio, Antonio, and Bernardino Campi) having established a strong tradition in nearby Cremona.

Key elements of Giovanni Battista's style include:

Narrative Clarity: In line with Counter-Reformation ideals, his religious scenes aimed to be legible and emotionally engaging, conveying sacred stories with directness.

Realism and Naturalism: While still within a Mannerist framework, there's a discernible effort towards realistic depiction of figures, settings, and emotions, a trend that would be further developed by the subsequent Baroque movement. Artists like Antonio Campi had already been pushing towards a more naturalistic and dramatic representation of light and form.

Rich Color Palette: Their paintings often feature vibrant and rich colors, contributing to the visual appeal and emotional impact of their works. This might show some residual influence from Venetian painting, perhaps transmitted through artists like Camillo Procaccini.

Architectural Elements and Perspective: Giovanni Battista was particularly skilled in rendering architectural settings and employing perspective to create a sense of depth and space. This is evident in many of his fresco cycles, where painted architecture seamlessly integrates with or expands the real architecture of the space.

Dynamic Compositions: Figures are often arranged in active, sometimes complex, groupings, with a sense of movement and drama that keeps the viewer engaged. Elongated figures, a hallmark of Mannerism, can also be observed.

Their style can be seen as a Lombard interpretation of late Mannerism, less intellectually abstruse than some Central Italian manifestations, and more grounded in a direct appeal to the viewer's piety. They were contemporaries of other important Milanese artists who were shaping the transition to the Baroque, such as Giovanni Battista Crespi, known as "Il Cerano" (1573–1632), Pier Francesco Mazzucchelli, "Il Morazzone" (1573–1626), and Giulio Cesare Procaccini (1574–1625, Camillo's brother), who collectively became the leading figures of early Milanese Baroque. While the Fiamminghi brothers' style remained more tied to Mannerist conventions, they were part of this evolving artistic landscape.

Major Commissions and Fresco Cycles

Giovanni Battista della Rovere, often with Giovanni Mauro, undertook numerous significant commissions, particularly extensive fresco decorations for churches. These large-scale projects allowed them to showcase their narrative skills and their ability to manage complex compositions over vast wall surfaces.

One of their most notable collaborative efforts was the decoration of the Chiaravalle Abbey, a Cistercian monastery near Milan. Here, they painted scenes from the life of St. Bernard and other Cistercian saints. Among these, the _Martyrdom of Saint Castillius_ (sometimes referred to as St. Celsus or other local saints depending on sources and interpretations), dated to around 1615, is a powerful example of their narrative style, depicting the dramatic intensity of the saint's suffering. They also contributed to the _Miracle of the Chains_ in the same abbey, showcasing their ability to handle complex multi-figure compositions.

The Milan Cathedral (Duomo di Milano) also benefited from Giovanni Battista's talents. He was involved in various decorative projects within the cathedral, a testament to his standing in the city. While specific attributions within such a vast and continuously evolving edifice can be complex, his participation is documented. This period saw significant work on the Duomo, including the creation of the famous Quadroni di San Carlo, large canvases depicting the life and miracles of Saint Charles Borromeo, by a team of artists including Il Cerano and Morazzone. Della Rovere's involvement would have been in similar decorative campaigns.

Other churches where Giovanni Battista and his brother left their mark include:

Santa Maria D'Agliacqua (or Santa Maria presso San Celso, depending on precise identification): They executed important fresco cycles here.

San Alessandro in Zebedia, Milan: Contributions to the decoration of this important Jesuit church.

Sant'Antonio Abate (formerly dei Teatini), Milan: Further fresco work.

Sant'Andrea: The specific church of Sant'Andrea is not always clearly identified in summaries, but it points to his activity in various Milanese ecclesiastical sites.

San Carlo al Corso (or a church dedicated to San Carlo Borromeo, possibly in Bologna as one source suggests "San Carlo di Bologna"): Their work extended beyond Milan, indicating a wider regional reputation.

He was also involved in the decoration of the Palazzo Regio Ducale (Royal Ducal Palace) in Milan. In 1597, he was among a group of esteemed artists, including Giovanni Ambrogio Figino and Camillo Procaccini, invited to contribute to its embellishment. This commission highlights his recognition not only for religious works but also for secular decorations in prestigious state buildings.

Furthermore, Giovanni Battista demonstrated his versatility by engaging in design work, such as the marble altar for the Savona Cathedral, indicating an understanding of three-dimensional design and its integration with painted elements.

Notable Easel Paintings

While renowned for their frescoes, the Fiamminghi brothers also produced a significant body of easel paintings, primarily altarpieces and devotional works on canvas or panel.

Among Giovanni Battista's representative works are:

_Saint Matthew_ (San Matteo): This painting, reportedly housed in Florence (perhaps in a less prominent church or collection, as it's not a widely cited Uffizi piece), showcases his ability to render individual saints with gravitas and psychological presence.

_The Blessing of a Cardinal_: Also noted as being in Florence, this work would likely depict a formal, ceremonial scene, allowing for the portrayal of rich vestments and a dignified assembly, themes common in ecclesiastical portraiture and narrative.

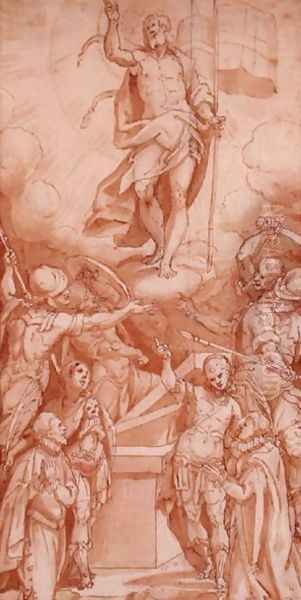

_Martyrdom of Saint Sebastian_: A theme frequently depicted in Christian art, offering opportunities for dramatic figure portrayal and emotional intensity. This was likely a collaborative work with Giovanni Mauro, emphasizing their joint approach to significant commissions.

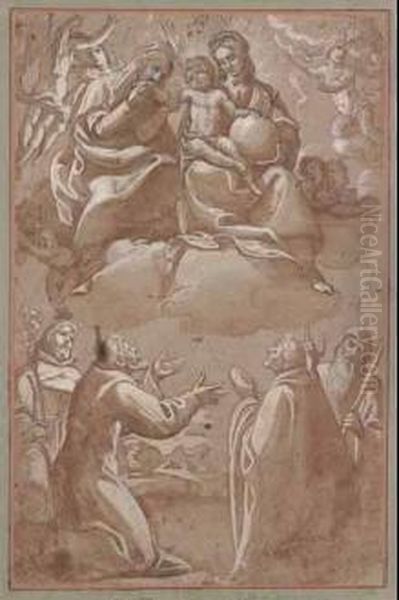

_Madonna con il Bambino in gloria e Santi_ (Madonna and Child in Glory with Saints): Described as a tempera painting in a private collection, this subject is a staple of Italian altarpieces. The "in gloria" aspect suggests a celestial vision, often with dynamic movement and a host of attendant figures.

_Meeting of Saints Carabolus and Filinonus_: While less information is readily available about these specific saints or the painting itself, its mention suggests a narrative work focusing on hagiography, a common theme in their oeuvre.

These works, whether solo or collaborative, would have shared the stylistic characteristics of their frescoes: strong narrative content, rich coloration, and a late Mannerist sensibility that balanced decorative elegance with devotional sincerity. His paintings would have been sought after for private chapels, confraternity meeting rooms, and church altars.

Challenges, Recognition, and Artistic Context

The provided information hints at some early career struggles for Giovanni Battista, particularly with "detail and color," leading to a lack of initial recognition. This is a plausible narrative for an emerging artist. The anecdote about gaining recognition through service to the "Duke of Urbino" and creating a large fresco of the Madonna and Saints (inspired by Giorgione or Titian) is interesting. However, the Della Rovere family of Urbino, which included Popes Sixtus IV and Julius II, was a different lineage from the Milanese painter's Flemish-rooted family. While not impossible that a Milanese artist might find patronage in Urbino, this specific story might involve some conflation or require more precise historical verification for Giovanni Battista, the "Fiamminghino." His primary sphere of documented activity remains firmly in and around Milan.

The competitive artistic environment of Milan would have presented its own challenges. Artists vied for prestigious commissions from the Church, the state, and wealthy patrons. Giovanni Battista and his brother carved out a successful niche, particularly in large-scale fresco work. Their ability to work efficiently as a team was likely a significant advantage.

The mention of a rivalry with Giovanni Battista Tiepolo (1696-1770) in the source material is an anachronism. Tiepolo belongs to a much later generation, a leading figure of the Venetian Rococo. Any contemporary rivalry Giovanni Battista della Rovere faced would have been with Milanese artists of his own time, such as the aforementioned Camillo Procaccini (though also a mentor), Il Cerano, Morazzone, or Giulio Cesare Procaccini, or perhaps lesser-known masters competing for similar commissions. The artistic debates of his era would have revolved around the interpretation of Mannerist principles versus the emerging naturalism and dynamism of the early Baroque, and the appropriate ways to represent religious subjects according to Counter-Reformation directives.

Cardinal Federico Borromeo was a towering figure in Milanese cultural life during Giovanni Battista's mature career. Borromeo was not only a religious leader but also a discerning art patron and collector, founding the Biblioteca Ambrosiana and the Pinacoteca Ambrosiana. His preferences leaned towards art that was clear, pious, and emotionally resonant, often favoring a Lombard naturalism. Artists like Il Cerano, Morazzone, and Daniele Crespi (c. 1598–1630) were among those who particularly flourished under his influence. While the Fiamminghi brothers' style was perhaps more traditional and less innovative than these early Baroque masters, their work fulfilled the ongoing need for devotional art and extensive church decoration.

Legacy and Art Historical Significance

Giovanni Battista della Rovere, along with his brother Giovanni Mauro, holds a respectable place in the history of Milanese painting. They were key figures in the continuation and popularization of the Late Mannerist style in Lombardy well into the early decades of the 17th century, a period when the Baroque was beginning to take hold.

Their main contributions can be summarized as:

Prolific Decorators: They were responsible for a vast output of religious art, particularly frescoes, adorning numerous churches and religious institutions. This made their work highly visible and influential within their region.

Narrative Skill: They excelled at translating religious stories into compelling visual narratives, fulfilling the didactic and devotional requirements of the Counter-Reformation Church.

Workshop Practice: Their successful collaborative workshop model allowed for the efficient execution of large-scale projects.

Transitional Figures: While not at the vanguard of the Baroque revolution initiated by artists like Caravaggio (who had his early training in Milan under Peterzano) or the Carracci in Bologna, the Fiamminghi represent an important phase of Late Mannerism that retained its appeal and relevance, particularly in more traditional ecclesiastical contexts. Their work shows an awareness of the growing taste for naturalism and emotionalism, even as it adheres to many Mannerist conventions.

Their art is perhaps less celebrated today than that of the groundbreaking figures who ushered in the Baroque, but they were vital to the artistic fabric of their time. They provided the visual language for religious devotion for a wide audience and contributed significantly to the rich artistic heritage of Milan and Lombardy. Their works can still be found in many churches and collections, offering valuable insights into the artistic currents and religious sensibilities of late 16th and early 17th-century Italy. Artists like Tanzio da Varallo (c. 1575/1580 – c. 1632/1633), another Lombard painter whose style blended Mannerist elements with a starker, more dramatic naturalism, would have been part of this broader artistic landscape.

Conclusion

Giovanni Battista della Rovere, "Il Fiamminghino," was a dedicated and highly productive painter whose career spanned a pivotal moment in Italian art history. Working closely with his brother Giovanni Mauro, he became a leading exponent of Late Milanese Mannerism, specializing in extensive fresco cycles and altarpieces that adorned countless sacred spaces. His art, characterized by narrative clarity, rich color, skilled perspective, and a devotional intensity aligned with Counter-Reformation ideals, served the spiritual needs of his community. While perhaps overshadowed in grand art historical narratives by the more revolutionary figures of the early Baroque, Giovanni Battista della Rovere and his brother were indispensable contributors to the visual culture of their era, leaving a lasting imprint on the artistic landscape of Lombardy and beyond. Their work remains a testament to the enduring power of religious narrative in art and the collaborative spirit of artistic workshops in early modern Italy.