Jacopo Amigoni stands as a pivotal figure in the landscape of 18th-century European art. An Italian painter of considerable talent and adaptability, he navigated the courts and artistic circles of Venice, Bavaria, England, and Spain, becoming one of the most sought-after exponents of the Rococo style. His prolific output spanned large-scale decorative frescoes, intimate mythological scenes, elegant religious paintings, and fashionable portraits. Amigoni's career exemplifies the internationalism of the Rococo movement, showcasing how Italian artistic traditions, particularly those of Venice, blended with French influences and adapted to the tastes of diverse patrons across the continent. His work, characterized by its light-filled palettes, graceful figures, and charming narratives, captured the essence of an era defined by elegance, pleasure, and sophisticated decoration.

Origins and Venetian Formation

The precise origins of Jacopo Amigoni remain somewhat shrouded in uncertainty, a common occurrence for artists of his time before the meticulous record-keeping of later centuries. Born around 1682, his birthplace is traditionally cited as either Naples or, perhaps more likely given his stylistic development, Venice. Some scholars suggest Neapolitan parentage, which might imply early exposure to the vibrant, dramatic art scene of Naples, possibly influenced by the legacy of artists like Luca Giordano. However, it was in Venice, the glittering city of canals and lagoons, that Amigoni truly forged his artistic identity. He is documented as being active there by 1711.

Venice in the early 18th century was a crucible of artistic innovation, particularly in painting. The city's long-standing emphasis on colorito (the primacy of color and brushwork) over Florentine disegno (drawing and design) provided fertile ground for the burgeoning Rococo sensibility. Amigoni entered this vibrant milieu, absorbing the influences of established masters and dynamic contemporaries. Key among his influences was Antonio Bellucci, a respected painter known for his decorative works. Amigoni may have trained or worked closely with Bellucci, whose style shows a transition from the heavier Baroque towards a lighter, more fluid manner.

Furthermore, Amigoni could not have ignored the impact of Sebastiano Ricci, another Venetian painter who enjoyed significant international success and whose works displayed a bright palette and dynamic compositions. Perhaps most significantly, Amigoni worked alongside the slightly younger, but already brilliant, Giovanni Battista Tiepolo. Tiepolo would become the undisputed giant of Venetian Rococo ceiling painting, and his luminous colours and airy compositions undoubtedly left an impression on Amigoni, even as their styles developed along distinct, though related, paths. The influence of painters like Giovanni Antonio Pellegrini, another internationally active Venetian decorative artist, also formed part of the artistic atmosphere Amigoni breathed.

During these formative years in Venice, Amigoni honed his skills, initially focusing on mythological and religious subjects, staples of the late Baroque and early Rococo repertoire. He developed a facility for creating appealing narratives populated by graceful figures, rendered with increasingly light and fluid brushwork. His early Venetian works laid the foundation for the style that would bring him fame across Europe, establishing his reputation within the competitive artistic landscape of La Serenissima.

The Bavarian Sojourn

Amigoni's rising reputation soon attracted attention beyond the Veneto. Around 1717, he embarked on the first major international phase of his career, travelling to Bavaria. This move was part of a broader pattern where Italian artists, particularly Venetians skilled in large-scale decorative painting, were highly sought after by German princes eager to embellish their palaces in the latest style. Amigoni found patronage under the Elector Maximilian II Emanuel of Bavaria, a ruler keen on importing Italian artistic flair.

For approximately a decade, from 1717 to 1727, Amigoni was primarily active in Bavaria, undertaking significant commissions for frescoes and decorative paintings. His most notable projects were at the Elector's palaces. At Nymphenburg Palace near Munich, he contributed significantly to the decoration, including frescoes in the Magdalenenklause, a hermitage pavilion in the palace park. These works often featured religious or allegorical themes, executed with a growing lightness and elegance that suited the intimate scale of the pavilion.

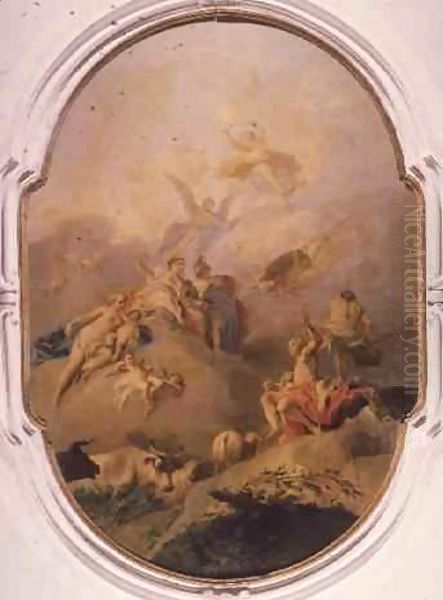

He also worked extensively at Schleissheim Palace, another electoral residence. Here, Amigoni painted impressive ceiling frescoes, demonstrating his mastery of large-scale composition and his ability to create airy, illusionistic spaces filled with mythological figures. These Bavarian works show Amigoni solidifying his Rococo style, moving further away from Baroque weightiness towards brighter colours, softer forms, and more playful narratives. His time in Germany allowed him to refine his technique in fresco, a demanding medium requiring speed and confidence, and established his credentials as a major decorative painter capable of handling prestigious courtly commissions. His success likely brought him into contact or competition with native German artists working in similar decorative modes, such as the Asam brothers, Cosmas Damian and Egid Quirin Asam, who were also active in Bavaria during this period.

The London Decade: Fame and Fashion

Following his successful stint in Bavaria, Amigoni returned briefly to Venice around 1726-1727, during which time he painted works like the Judgement of Paris, now housed in the Villa Pisani at Stra. However, his sights were soon set on another major European capital: London. He arrived in England in 1729 and remained there for a decade, until 1739. This period marked a significant high point in his career, bringing him considerable fame, numerous commissions, and integration into London's fashionable society.

England in the 1730s offered different opportunities compared to Bavaria. While there was less demand for vast religious or mythological fresco cycles in churches or palaces, there was a thriving market for decorative paintings in aristocratic homes and, crucially, for portraiture. Amigoni adapted his talents accordingly. He undertook decorative schemes for grand houses, such as Moor Park in Hertfordshire, where he painted mythological scenes that adorned the interiors with Continental elegance. He also reportedly worked for the Covent Garden Theatre, though these works are now lost.

His skill in portraiture, however, proved particularly popular. Amigoni developed a style that flattered his sitters, depicting them with grace, elegance, and a certain idealized charm, perfectly suited to the Rococo aesthetic. He painted members of the royal family and numerous aristocrats. Perhaps his most famous connection during this time was with the celebrated Italian castrato singer, Carlo Broschi, known as Farinelli. Farinelli was a sensation in London's opera scene, and he and Amigoni became close friends. Amigoni painted several portraits of the singer, including the well-known group portrait The Singer Farinelli and his Friends (c. 1750-52, but conceived based on their London relationship), which captures the singer amidst his circle of admirers and fellow artists, including Amigoni himself.

Amigoni's presence was noted in London's cultural circles. The novelist Henry Fielding even mentions him in his novel Joseph Andrews, attesting to the painter's visibility. Despite his success, Amigoni's idealized portrait style sometimes drew criticism for lacking the robust realism favoured by some English tastes, perhaps contrasting with the more psychologically penetrating or satirical works of native artists like William Hogarth. Contemporary portraitists like Allan Ramsay offered a different, perhaps more restrained, style. Nevertheless, Amigoni's elegant, Continental manner was highly fashionable, and his London years were financially rewarding, allowing him to return to Venice in 1739 reportedly "with a small fortune."

Parisian Interlude and Venetian Return

During his productive decade based in London, Amigoni made a significant trip to Paris in 1736. This visit placed him directly in the heartland of the Rococo style's development. While in Paris, he continued his association with his friend Farinelli, collaborating on a portrait. More importantly, this journey provided Amigoni with the opportunity to engage directly with the leading figures of French Rococo painting.

Records suggest he met or at least familiarized himself further with the works of prominent French artists such as François Lemoyne, known for his large-scale decorative works, including the ceiling of the Salon d'Hercule at Versailles. He also encountered the circle of François Boucher, who was rapidly becoming the epitome of French Rococo painting with his charming mythological scenes, pastoral landscapes, and decorative designs. Although the foundational figure of French Rococo, Jean-Antoine Watteau, had passed away earlier, his influence permeated the artistic atmosphere Amigoni experienced. This Parisian exposure likely reinforced Amigoni's own Rococo inclinations, perhaps encouraging the lighter palette, more sensuous figure types, and playful themes already present in his work.

Upon leaving England in 1739, Amigoni returned to Venice. He remained there for several years, resuming his activity in the city that had first nurtured his talent. He continued to receive commissions, working for both churches and private patrons. His international reputation preceded him, ensuring he remained a significant figure in the Venetian art scene, alongside the dominant Tiepolo and other contemporaries like Giovanni Battista Piazzetta, known for his more tenebrous style. This period saw him further consolidate his mature style, blending his Venetian roots with the experiences gained in Germany, England, and France.

The Spanish Finale: Court Painter in Madrid

The final chapter of Jacopo Amigoni's extensive international career unfolded in Spain. In 1747, drawn by the prospect of prestigious royal patronage, he moved to Madrid. This was a significant appointment: he was named First Court Painter to King Ferdinand VI. This role placed him at the apex of the artistic hierarchy in Spain, responsible for producing works for the monarch and overseeing aspects of the royal collections and decorative projects.

His position was further solidified when he was appointed Director of the newly established Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando (Royal Academy of Fine Arts of San Fernando) in 1752, shortly before his death. This role underscored his esteemed status and influence within the Spanish art world. In Madrid, Amigoni continued to paint portraits of the royal family and members of the court, as well as undertaking decorative commissions for royal residences, such as the Palacio Real de Aranjuez.

His elegant, light-filled Rococo style offered a contrast to the more sombre traditions of Spanish Baroque painting, though Spain was also receptive to international trends. Amigoni's presence in Madrid brought the latest iteration of Venetian Rococo directly to the Spanish court. During his time there, he would have been aware of Spanish contemporaries, perhaps figures like the still-life painter Luis Meléndez, although their artistic concerns differed greatly. Amigoni's tenure also preceded the arrival of Anton Raphael Mengs, a key figure in the transition towards Neoclassicism, who would soon dominate the Madrid art scene after Amigoni's death. Amigoni's student and long-time friend, the French painter Charles Joseph Flipart, accompanied him to Spain and continued to work there after Amigoni's passing.

Jacopo Amigoni died in Madrid in 1752, concluding a remarkably successful and geographically diverse career. His final years as court painter in Spain cemented his reputation as a leading master of the European Rococo, whose art had graced palaces and collections from Bavaria to Britain to Spain.

Amigoni's Artistic Signature: Style and Development

Jacopo Amigoni's art is synonymous with the elegance, lightness, and decorative charm of the Rococo era, yet it possesses a distinct character shaped by his Venetian origins and international experiences. His style evolved throughout his career but consistently displayed several key features that define his artistic signature.

Rococo Sensibility: At its core, Amigoni's work embodies the Rococo spirit. He favoured themes of pleasure, grace, and intimacy, moving away from the high drama and emotional intensity of the Baroque. His mythological scenes often depict gods and goddesses in moments of leisure, love, or playful interaction, rather than epic conflict. Even his religious paintings frequently possess a gentle, approachable quality, rendered with soft colours and elegant figures. This pursuit of joie de vivre and refined sensibility is a hallmark of his oeuvre.

Color Palette and Light: Drawing heavily on the Venetian tradition of colorito, Amigoni employed a distinctive palette. His colours are typically bright, luminous, and often favour pastel shades – pinks, blues, yellows, and silvery greys dominate many of his canvases. He masterfully handled light, suffusing his scenes with an airy, often ethereal glow. This contrasts sharply with the dramatic chiaroscuro of the earlier Baroque. His use of colour and light contributes significantly to the overall feeling of lightness and elegance in his work.

Brushwork and Form: Amigoni's brushwork is characteristically fluid, rapid, and feathery. He often used visible, delicate strokes (sometimes referred to as pittura di tocco – painting of touch) that lend texture and vibrancy to the surface. His figures are gracefully drawn, often elongated, with soft contours and elegant postures. He avoided harsh lines, preferring forms that seem to dissolve gently into the surrounding atmosphere. This technique enhances the sense of movement and lightness inherent in the Rococo aesthetic.

Composition: Amigoni favoured dynamic and asymmetrical compositions, often employing the characteristic S-curves and C-curves of the Rococo style to guide the viewer's eye and create a sense of flowing movement. In his decorative frescoes, he skillfully integrated figures, architectural elements, and ornamental motifs into unified, harmonious schemes that delight the eye without overwhelming it. His compositions feel open and airy, contributing to the overall decorative effect.

Themes and Subject Matter: While adept at portraiture, Amigoni excelled in mythological and allegorical subjects. He had a particular fondness for tales from Ovid, depicting scenes like Venus Disarming Cupid, Bacchus and Ariadne, or the Judgement of Paris. These themes allowed him to explore ideals of beauty, love, and pleasure. His religious works, while sincere, often adopt the same graceful style. His portraits, particularly those from his London period, capture the elegance and social aspirations of his sitters, though sometimes sacrificing deep psychological insight for idealized representation.

Synthesis and Innovation: Amigoni's key innovation lay in his ability to synthesize various influences – the colourism of Venice (Ricci, Pellegrini), the decorative grandeur learned perhaps from Bellucci, the burgeoning luminosity of Tiepolo, and the elegance of French Rococo (Boucher, Lemoyne) – into a coherent and highly appealing personal style. He successfully adapted this style to different media (easel painting, fresco) and diverse patronage across Europe, demonstrating remarkable versatility.

Masterworks in Focus

Jacopo Amigoni's prolific career left behind a rich body of work. Several key paintings and decorative cycles stand out as representative of his style and achievements:

Venus Disarming Cupid: Variations of this theme appear in Amigoni's work, perfectly encapsulating the Rococo fascination with playful mythology and sensuous beauty. These paintings typically feature graceful figures, soft flesh tones, pastel colours, and a lighthearted atmosphere, showcasing Venus gently taking away the mischievous Cupid's bow and arrows. It highlights his delicate brushwork and ability to render textures like silk and skin.

The Embarkation of Helen of Troy: Tackling a subject linked to epic conflict, Amigoni treats it with characteristic Rococo elegance rather than martial drama. The focus is on the graceful figures, the rich fabrics, and the overall decorative composition. It demonstrates his ability to handle multi-figure narrative scenes within his distinct stylistic framework.

Narcissus and Cupid: This work explores another popular mythological tale, allowing Amigoni to delve into themes of beauty, self-love, and gentle melancholy. The rendering of the figures and the landscape setting would typically display his soft focus and luminous palette, capturing the poetic essence of the myth.

Bacchus and Ariadne: A subject favoured by Venetian artists since Titian, Amigoni's interpretations usually emphasize the celebratory and romantic aspects of the myth. Expect dynamic compositions, vibrant colours (though softened in his Rococo manner), and graceful figures embodying the joyous union of the god of wine and the Cretan princess.

The Singer Farinelli and his Friends: This group portrait is significant not only for its artistic merit but also as a social document. It depicts the famous castrato surrounded by his admirers, including the poet Pietro Metastasio and Amigoni himself. The composition is informal yet elegant, capturing a moment of sophisticated camaraderie. It showcases Amigoni's skill in portraiture and his connection to the cultural elite of his time.

Judgement of Paris (Villa Pisani, Stra): Painted after his return from Bavaria, this work exemplifies his mature Venetian style before the London sojourn. It presents the famous beauty contest between goddesses with elegance and charm, allowing Amigoni ample opportunity to depict idealized female beauty and rich drapery against a pleasant landscape.

Fresco Cycles (Bavaria): While individual easel paintings are more widely known, his large-scale fresco decorations in palaces like Nymphenburg and Schleissheim represent major achievements. These ambitious projects demonstrate his mastery of fresco technique and his ability to create immersive decorative environments filled with light, colour, and graceful mythological or allegorical figures, perfectly suited to the opulent interiors of Rococo palaces.

Network, Influence, and Legacy

Jacopo Amigoni was not an isolated artist but an active participant in the bustling international art world of the 18th century. His extensive travels and prestigious appointments facilitated connections with a wide network of artists, patrons, and cultural figures, and his work left a discernible mark on the development of Rococo art across Europe.

Mentorship and Collaborations: Amigoni played a role in nurturing the next generation of artists. His most notable student and long-term associate was the French painter Charles Joseph Flipart, who accompanied him to Madrid and remained there after his death, continuing to work in a style influenced by his master. He also had connections with sculptors like Michelangelo Morlaiter in Venice. His workshop likely employed various assistants throughout his career, helping to execute large commissions.

Influence on Contemporaries: Amigoni's elegant and accessible style influenced several contemporaries. In Venice, painters like Giuseppe Nogari, known for his character heads and portraits, show an affinity with Amigoni's refined manner. His impact extended through the dissemination of his designs via engravings. The engraver Joseph Wagner, who worked in Venice, produced numerous prints after Amigoni's paintings, significantly broadening the reach of his compositions and style across Europe, making his popular mythological and allegorical scenes available to a wider audience and influencing artists and craftsmen in various fields.

Cultural Connections: Beyond fellow artists, Amigoni moved in sophisticated circles. His close friendship with the opera superstar Farinelli is well-documented through portraits and correspondence. His mention by the English novelist Henry Fielding attests to his recognition within London's literary and social scene. These connections highlight his integration into the broader cultural fabric of the era.

Place in Rococo Art: Amigoni is considered a leading figure of the Venetian Rococo and a key conduit for transmitting Italian, particularly Venetian, artistic ideas northward and westward. He successfully blended the colouristic tradition of Venice with the elegance associated with French Rococo, creating a style that found favour in German courts, English townhouses, and the Spanish royal palace. He demonstrated the adaptability of the Rococo style, capable of gracing both intimate canvases and vast ceiling frescoes.

Legacy: While his fame was somewhat eclipsed in the later 18th century by the rise of Neoclassicism (represented by artists like Anton Raphael Mengs who arrived in Madrid shortly after his death), Amigoni's contribution remains significant. He represents the international triumph of the Rococo style, an artist whose talent transcended borders. His works continue to be admired for their charm, elegance, technical finesse, and their embodiment of the sophisticated tastes of the 18th-century European elite. He remains a crucial figure for understanding the diffusion and variation of Rococo art beyond France.

In conclusion, Jacopo Amigoni emerges from the historical record as a highly skilled, adaptable, and successful painter who played a significant role in shaping and disseminating the Rococo style across Europe. From his Venetian roots, through his productive years in Bavaria and England, to his final prestigious appointment at the Spanish court, Amigoni consistently produced works characterized by elegance, light, and charm. His mastery of colour, fluid brushwork, and appealing subject matter made him a favourite among aristocratic and royal patrons. As a key exponent of the international Rococo, his legacy lies not only in his beautiful paintings and frescoes but also in his role as a cultural bridge, connecting the artistic centres of 18th-century Europe.