Giovanni Francesco Castiglione (1641–1710) was an Italian painter active during the High Baroque period. He was the son of the highly influential Genoese artist Giovanni Benedetto Castiglione, known as Il Grechetto, a towering figure whose innovative work in painting and printmaking cast a long shadow. Giovanni Francesco largely followed in his father's artistic footsteps, specializing in the pastoral landscapes, animal paintings, and biblical or mythological scenes that had brought his father renown. While he may not have achieved the same level of groundbreaking originality as Il Grechetto, Giovanni Francesco played a significant role in continuing the family workshop and perpetuating a distinctive style, particularly at the court of Mantua.

Early Life and the Overwhelming Influence of Il Grechetto

Born in Genoa in 1641, Giovanni Francesco Castiglione was immersed in art from his earliest years. His father, Giovanni Benedetto Castiglione (c. 1609–1664), was a dynamic and innovative artist, celebrated for his vibrant pastoral scenes, his dramatic depictions of Old Testament stories often populated with animals, and his pioneering work in printmaking, including the invention of the monotype. The elder Castiglione was a restless figure, working in Genoa, Rome, Naples, Venice, and eventually Mantua, absorbing and synthesizing a wide range of influences.

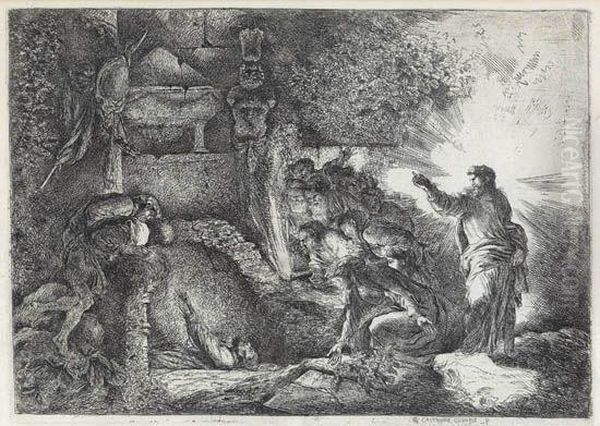

Growing up in such an environment, it was natural for Giovanni Francesco to train under his father. He would have learned firsthand the techniques of oil painting, drawing, and possibly etching, which his father had mastered. The elder Castiglione's style was characterized by a rich, painterly application of pigment, dramatic lighting reminiscent of the tenebrism of earlier masters but with a more flickering, vibrant quality, and a remarkable ability to capture the textures and movements of animals. His subjects often included journeys of patriarchs like Abraham, Noah, Jacob, and Rebecca, always accompanied by lively assortments of livestock, dogs, and exotic creatures.

The artistic milieu of Genoa itself was rich. During the early 17th century, the city had been a magnet for Flemish artists like Peter Paul Rubens and Anthony van Dyck, whose opulent portraits and dynamic compositions left an indelible mark. Local Genoese masters such as Bernardo Strozzi and Sinibaldo Scorza, the latter an early specialist in animal painting, also contributed to a vibrant artistic scene. Giovanni Benedetto absorbed these influences, particularly the Flemish emphasis on rich color and texture, and the pastoral traditions. This was the artistic inheritance passed down to Giovanni Francesco.

Artistic Style and Thematic Concerns

Giovanni Francesco Castiglione's own artistic output is primarily understood as a continuation and, at times, a direct imitation of his father's work. This was not uncommon in an era where family workshops often maintained a consistent "brand" or style. His paintings frequently feature the same themes: pastoral landscapes with shepherds and their flocks, mythological episodes set in rustic surroundings, and compositions teeming with animals.

Some art historians suggest subtle differences in their approach. While Giovanni Benedetto often employed a vigorous, sometimes impastoed brushwork, Giovanni Francesco's handling could be somewhat smoother or more meticulous. The provided information suggests that Giovanni Francesco might have favored "brighter saturated colors and the subtle transparency of watercolor" in some works, contrasting with his father's "bold use of oil paints." This distinction, particularly regarding watercolor, would indicate a proficiency in drawing and works on paper, a medium his father also excelled in.

His animal paintings, like those of his father, demonstrate a keen observation of animal anatomy and behavior. These were not mere background elements but often the central focus of the composition, imbued with life and character. The tradition of animal painting in Genoa was strong, with artists like Jan Roos (Giovanni Rosa), a Fleming active in Genoa, and Frans Snyders (whose works were known in Genoa) providing precedents for detailed and lively animal depictions. Giovanni Francesco continued this tradition, often creating scenes where animals dominate the canvas.

Notable Works and Attributions

Identifying and attributing works solely to Giovanni Francesco can sometimes be challenging due to the close stylistic similarities with his father and the collaborative nature of the workshop. However, several works are generally accepted as his or are characteristic of his hand.

The painting titled "A Congress of Animals" is mentioned as a representative piece. Such a theme, showcasing a variety of animals in a landscape, is entirely consistent with the Castiglione workshop's output. The description of it "imitating the tradition of Dutch and Flemish animal painting, using fine lines to outline contours and the subtle transparency of watercolor" points to a refined technique, possibly in a drawing or a highly finished oil sketch. If watercolor was indeed a preferred medium for certain effects, it would align with his father's mastery of drawing with brush and wash.

Other works mentioned, such as "Boy with a Dog Playing in a Meadow" executed in "pen, ink, watercolor, and gouache," further underscore his activity as a draftsman and painter on paper. "Animals and Birds Playing in a Landscape" is another typical theme. The somewhat speculative iconographic link to Arthurian legend ("lion as 'animal king'") seems less probable for the Italian Baroque context unless specifically commissioned with such a program, but the general theme of animals in a landscape is central to his oeuvre.

Many works simply titled "Pastoral Scene," "Noah Leading the Animals into the Ark," or "Journey of a Patriarch" exist, and distinguishing between the father, the son, and workshop assistants requires careful connoisseurship. Giovanni Francesco's role was likely to produce variations on successful compositions by his father, catering to the continued market demand for such pictures.

Court Painter in Mantua

A significant phase in Giovanni Francesco's career was his appointment as court painter to Ferdinando Carlo Gonzaga, the last Duke of Mantua, in 1682 (some sources state 1681). This was a prestigious position, one that his father, Giovanni Benedetto, had also held from 1651 until his death in Mantua in 1664. The Gonzaga court, though past its Renaissance zenith when artists like Andrea Mantegna and Giulio Romano had made it one of Europe's leading cultural centers, still maintained a degree of artistic patronage.

By continuing in his father's role, Giovanni Francesco would have been responsible for producing paintings for the ducal collections, decorating palace interiors, and possibly designing for courtly events. His animal and pastoral scenes would have appealed to the aristocratic taste for subjects that evoked a bucolic ideal or showcased the variety of the natural world. The Duke's patronage provided a degree of stability and recognition.

However, the political fortunes of the Gonzaga dynasty were in decline. Ferdinando Carlo's reign was marked by political missteps, and Mantua's power waned. The provided information notes that Giovanni Francesco's career suffered with the decline of the Gonzaga family around 1708, when Mantua was occupied by Austrian forces. This political turmoil would undoubtedly have impacted court patronage.

The Castiglione Workshop and Artistic Legacy

After Giovanni Benedetto's death in 1664, Giovanni Francesco would have been the principal figure in maintaining the Castiglione workshop. He likely managed assistants and oversaw the production of paintings in the established family style. This continuation was vital for preserving and disseminating his father's artistic innovations. While perhaps not an innovator on the scale of Il Grechetto, Giovanni Francesco's dedication to his father's manner ensured that this unique blend of Genoese vibrancy, pastoral poetry, and dynamic animal depiction remained current for several more decades.

His father's influence extended beyond his immediate family. Artists in Genoa, such as Valerio Castello, who was a contemporary of Giovanni Benedetto, and later figures like Domenico Piola and Gregorio de Ferrari, absorbed elements of Il Grechetto's dynamic compositions and rich colorism into their own work, contributing to the distinctive character of the Genoese Baroque school. Giovanni Francesco's continued presence, particularly in Mantua, would have served as a living link to this influential style.

The elder Castiglione was also a profound influence on later 18th-century artists, particularly in Venice. Figures like Giovanni Battista Tiepolo, Francesco Zuccarelli, and Giuseppe Zais admired his pastoral scenes and free brushwork. While Giovanni Francesco's direct impact might be less easily traced, his role in preserving and continuing his father's legacy contributed indirectly to this later appreciation.

Distinguishing Father from Son: A Matter of Nuance

The close stylistic relationship between Giovanni Francesco and his father, Giovanni Benedetto, has often led to confusion in attributions. Furthermore, the provided source material itself shows some conflation, attributing certain biographical details or works more commonly associated with the father (or even entirely different artists) to the son.

For instance, the mention of a tumultuous life with multiple imprisonments for assault and theft is a well-documented aspect of Giovanni Benedetto "Il Grechetto" Castiglione's biography. His fiery temperament and legal troubles are legendary. While it's not impossible for a son to share personality traits, these specific and repeated incidents are strongly tied to the father. Similarly, the invention of the monotype and the profound influence of Rembrandt's etchings are hallmarks of Giovanni Benedetto's career. Giovanni Francesco would have learned these techniques and styles, but the innovation belongs to the father.

The reference to a painting titled "The Creation of Adam" is almost certainly an error, as this is the title of Michelangelo's iconic fresco in the Sistine Chapel and not a subject typically associated with either Castiglione, nor a work by them.

The information about Giovanni Francesco becoming impoverished and dying in Genoa, buried in a common grave in San Martino church, also requires careful handling. While his father did spend significant time in Genoa and had a somewhat erratic career, Giovanni Benedetto died and was buried in Mantua. Standard art historical sources often give Giovanni Francesco's death year as 1716, also in Mantua. The provided date of 1710 and the Genoese death location might reflect a specific, perhaps less common, account or a confusion with another individual. The decline of his Mantuan patronage after 1708 could certainly have led to financial difficulties in his later years.

Contemporaries and the Broader Artistic Milieu

Giovanni Francesco Castiglione operated within a rich artistic landscape. His father was a contemporary of major figures of the Italian Baroque, including:

In Rome: Nicolas Poussin and Claude Lorrain, who were developing classical landscape painting; Pietro da Cortona, a master of exuberant Baroque ceiling frescoes; and the sculptor Gian Lorenzo Bernini. Salvator Rosa, known for his wild, romantic landscapes and battle scenes, was another contemporary.

In Genoa: Bernardo Strozzi, whose robust, painterly style was influential; Valerio Castello, known for his dynamic and light-filled compositions; and later, Domenico Piola and Gregorio de Ferrari, who carried the Genoese Baroque into the late 17th and early 18th centuries.

Northern Artists (influential on his father, and thus part of his artistic DNA): Anthony van Dyck, whose Genoese period left a lasting impact on portraiture and elegant composition; Peter Paul Rubens, whose dynamism was pervasive; Frans Snyders and Jan Roos, who specialized in animal and still-life painting. The etchings of Rembrandt van Rijn were a significant inspiration for Giovanni Benedetto's own printmaking.

While Giovanni Francesco was younger than many of these luminaries, their work formed the backdrop against which his own art, and that of his father, was created and understood. His direct contemporaries in Mantua would have included other court artists, though perhaps none with the specific specialization of the Castiglione workshop.

Later Years and Historical Assessment

The final years of Giovanni Francesco Castiglione are less clearly documented than his period as Mantuan court painter. If his patronage from the Gonzaga court indeed diminished significantly after 1708, he may have faced challenging circumstances. The discrepancy in death dates (1710 vs. 1716) and locations (Genoa vs. Mantua) highlights the difficulties in tracing the lives of artists who were not at the absolute forefront of innovation or fame.

In art historical terms, Giovanni Francesco is primarily valued as a faithful follower and continuer of his father's style. He was a competent and skilled painter who capably reproduced the pastoral and animal-rich compositions that had made the Castiglione name famous. He did not radically depart from his father's artistic vision or forge a strikingly original path. However, his role in the family workshop, his service to the Mantuan court, and his perpetuation of a popular and influential style grant him a secure, if secondary, place in the history of Italian Baroque art.

His works, and those of the Castiglione workshop more broadly, catered to a persistent taste for idyllic landscapes, scenes of rustic life, and depictions of the animal kingdom. These themes offered an escape from the formalities of urban or courtly life and resonated with a pastoral literary tradition.

Conclusion: A Legacy of Continuity

Giovanni Francesco Castiglione's career is a testament to the enduring power of artistic inheritance and the dynamics of family workshops in the Baroque era. Born into the legacy of a truly exceptional and innovative father, Il Grechetto, he dedicated his artistic life to mastering and perpetuating that distinctive style. His paintings of animals, shepherds, and ancient journeys, rendered with skill and often a charming vivacity, found favor at the Mantuan court and with private collectors.

While he may not be celebrated for groundbreaking innovations, Giovanni Francesco's contribution lies in his steadfast continuation of a unique artistic vision. He ensured that the imaginative world created by his father – a world filled with flickering light, dynamic movement, and a profound sympathy for the natural world – remained accessible to audiences for another generation. His work serves as an important link in the chain of the Castiglione artistic dynasty and as a representative example of a successful, if not revolutionary, painter within the rich tapestry of Italian Baroque art. His paintings continue to be appreciated for their decorative qualities, their skilled depiction of animals, and as echoes of his father's more famous genius.