Introduction: Unveiling a Venetian View Painter

In the vibrant artistic landscape of 18th-century Venice, a city renowned for its unique beauty and thriving cultural scene, the genre of veduta, or view painting, reached unprecedented heights. While names like Canaletto and Guardi often dominate discussions of this period, other talented artists contributed significantly to capturing the essence of La Serenissima. Among them was Johann Richter (1665-1745), a painter whose Swedish origins add a fascinating dimension to his engagement with the Venetian environment. Often Italianized as "Giovanni," his correct name reflects his Northern European roots. Richter carved a niche for himself by meticulously and poetically depicting the city's famous landmarks, lesser-known corners, and the bustling life along its canals and squares.

Born in Stockholm in 1665, Richter's journey led him to Venice, the heart of veduta painting. He arrived during a period when the city was a primary destination for the Grand Tour, creating a fervent market for souvenir views among wealthy European travelers. Richter immersed himself in this artistic milieu, eventually developing a distinct style that, while rooted in the topographical accuracy demanded by the genre, also possessed a unique atmospheric quality. He became known for his oil paintings capturing iconic sites such as St. Mark's Basin, the church of Santa Maria della Salute, and the Dogana da Mar (Customs House), as well as more intimate scenes of daily Venetian life. His career, spanning into the mid-18th century, places him as a contemporary of the genre's pioneers and masters, contributing his own perspective to the visual legacy of Venice.

From Stockholm to the Lagoon: An Artist's Journey

Details surrounding Johann Richter's early life and artistic training in Sweden remain relatively scarce. Born in Stockholm during a period when Sweden was a significant Northern European power, he would have grown up in an artistic environment influenced by Dutch and Flemish traditions, as well as court painters like David Klöcker Ehrenstrahl. However, like many artists from Northern Europe during the 17th and 18th centuries, the allure of Italy, particularly Rome and Venice, proved irresistible. Italy was considered the ultimate finishing school for artists, offering exposure to classical antiquity, Renaissance masterpieces, and a vibrant contemporary art scene.

The exact date of Richter's arrival in Venice is uncertain, but it likely occurred in the late 17th or early 18th century. He entered a city that was not only visually stunning but also a hub of artistic innovation and patronage. Venice's unique topography, architectural marvels, luminous atmosphere, and ceremonial life provided endless inspiration for artists. The growing demand for vedute, fueled by the influx of Grand Tourists eager to bring home mementos of their travels, created fertile ground for painters specializing in cityscapes. Richter found himself in the right place at the right time to develop his talents within this specific and highly popular genre.

The Rise of the Veduta and the Venetian Context

The 18th century witnessed the golden age of Venetian painting, marked by a flourishing of various genres. While history painting, led by figures like Giambattista Tiepolo and Sebastiano Ricci, continued the grand traditions, new forms gained prominence. Portraiture, especially the delicate pastels of Rosalba Carriera, captured the elegance of the era's elite. Genre painting, depicting scenes of everyday Venetian life, found a master in Pietro Longhi. Within this diverse artistic production, the veduta emerged as perhaps the most characteristic and internationally sought-after genre.

Veduta painting involved the detailed, largely topographical depiction of cityscapes or landscapes. In Venice, this meant capturing the intricate network of canals, the magnificent palaces lining the Grand Canal, the expansive Piazza San Marco, the numerous churches, and the surrounding lagoon islands. These paintings were more than mere postcards; they were carefully composed works of art that celebrated the city's unique character, its architectural splendor, and its vibrant public life. They appealed immensely to the Grand Tourists – predominantly British, German, and French aristocrats and intellectuals – who sought sophisticated souvenirs of their cultural pilgrimage.

Under the Influence: Luca Carlevaris

Johann Richter's development as a veduta painter was significantly shaped by the pioneering work of Luca Carlevaris (1663-1730). Carlevaris, slightly older than Richter, is widely regarded as the founder of the 18th-century Venetian veduta tradition. His meticulously detailed and expansive views, often featuring large crowds during festivals and ceremonies, set the standard for the genre. Carlevaris brought a new level of topographical accuracy and compositional structure to view painting, moving beyond earlier, more decorative map-like representations.

It is highly probable that Richter either studied directly with Carlevaris or was deeply influenced by his work upon arriving in Venice. The source material mentions Richter learning from "Carlije," almost certainly a reference to Carlevaris. Richter adopted the careful attention to architectural detail and the structured compositions characteristic of Carlevaris. However, as Richter's own style matured, particularly from the 1730s onwards, he began to distinguish himself, developing what the sources describe as his "unique artistic language." While maintaining accuracy, Richter's work often seems to possess a slightly softer atmosphere and a more lyrical quality compared to the sometimes starker precision of Carlevaris.

Richter's Artistic Signature: Style and Technique

Johann Richter's artistic style is characterized by a blend of realism and poetic sensibility. His paintings are grounded in careful observation of Venetian architecture and topography, yet they transcend mere documentation. He possessed a keen eye for the interplay of light and shadow, using it to define forms, create depth, and evoke the specific atmosphere of the lagoon city – the hazy mornings, the bright midday sun, or the tranquil twilight. His color palette is often described as lively and fresh, contributing to the overall vibrancy of his scenes.

Richter demonstrated skill in composition, often choosing interesting viewpoints that offered fresh perspectives on familiar landmarks. He might employ central perspective to emphasize the grandeur of a building like the Salute church or use a slightly elevated viewpoint to encompass a broader panorama of the Bacino di San Marco (St. Mark's Basin). Crucially, his vedute were rarely empty architectural studies. He populated his scenes with small figures – gondoliers, merchants, elegantly dressed ladies and gentlemen, common folk – engaged in everyday activities. These figures add life, scale, and narrative interest to the paintings, providing glimpses into 18th-century Venetian society, such as the documented detail of women reading newspapers near St. Mark's. This integration of the human element within the meticulously rendered cityscape is a hallmark of his approach.

Capturing La Serenissima: Subject Matter

Johann Richter's oeuvre focused almost exclusively on Venice and its surroundings. He painted the city's most iconic sites, catering to the demands of the Grand Tour market, but also explored less common vistas, demonstrating a deep familiarity with the city's diverse environments. His subjects included the heart of Venice: the Piazzetta, with the Doge's Palace, the Sansovino Library, the towering Campanile (bell tower), and the elegant Loggetta at its base. He depicted the bustling expanse of the Bacino di San Marco, often showing the Dogana da Mar (Customs House) with its distinctive golden globe and the majestic church of Santa Maria della Salute dominating the entrance to the Grand Canal.

Beyond the central areas, Richter ventured to the islands of the lagoon. He painted views of San Michele in Isola, known for its church and monastery (later Venice's primary cemetery), and Murano, the center of Venice's renowned glassmaking industry. These island views often possess a particular tranquility, contrasting with the energy of the city center. His ability to capture both the monumental scale of Venice's landmarks and the more intimate charm of its quieter corners showcases the breadth of his engagement with the city. The inclusion of daily life, whether it be boats navigating the waterways or figures animating the squares and fondamenta (waterside walkways), consistently grounds his architectural depictions in a lived reality.

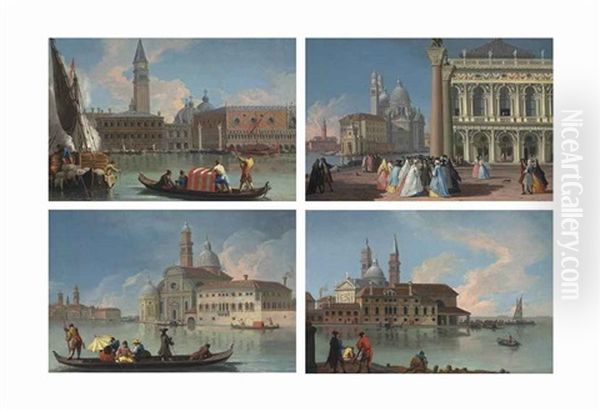

Representative Works: "Four Views of Venice"

Among the works specifically mentioned as representative of Richter's mature style is a set titled "Four Views of Venice." While the exact compositions within this specific set might vary or require specific identification in collections, such sets were common commissions during the period. Typically, a set of four views would aim to provide a comprehensive visual tour of the city's highlights. It might include a view of the Piazza San Marco, a perspective along the Grand Canal featuring prominent palaces, a depiction of the Bacino di San Marco with the Salute and Dogana, and perhaps a view capturing a specific festival or a scene from the outer lagoon.

Such a set, attributed to his mature period (likely mid-1730s onwards), would exemplify the characteristics that defined his unique contribution: the blend of topographical accuracy with atmospheric effect, the skillful handling of light and water, the lively inclusion of figures, and perhaps the innovative compositional choices that distinguished him from his contemporaries. These works encapsulate his ability to convey not just the physical appearance of Venice, but also its unique spirit – a city simultaneously grand and intimate, bustling and serene. The creation of such sets highlights his success in catering to the sophisticated tastes of international collectors seeking high-quality souvenirs of their Venetian experience.

The Venetian Art World: Contemporaries and Connections

Johann Richter worked within one of the most dynamic artistic centers in 18th-century Europe. His career overlapped with several key figures who shaped the Venetian art scene. His primary point of reference in the veduta genre was undoubtedly Luca Carlevaris. As Richter matured, he would have witnessed the meteoric rise of Antonio Canal, better known as Canaletto (1697-1768). Canaletto, initially trained as a theatre-set painter like his father, brought an unparalleled level of luminosity, precision, and compositional brilliance to the veduta, becoming the most celebrated view painter of his time, particularly favored by English patrons through his agent Joseph Smith.

Other significant vedutisti included Canaletto's talented nephew, Bernardo Bellotto (1721-1780), who adopted his uncle's style but often imbued it with cooler light and sharper detail, later working extensively in Dresden, Vienna, and Warsaw. Michele Marieschi (1710-1743) offered a more dramatic and painterly alternative with his dynamic compositions and energetic brushwork, though his career was cut short by his early death. Emerging towards the end of Richter's life and flourishing afterwards was Francesco Guardi (1712-1793), whose vedute increasingly moved away from strict topographical accuracy towards more atmospheric, evocative, and sketch-like depictions, capturing the decaying romance of Venice in a manner distinct from Canaletto's crystalline clarity.

Beyond the vedutisti, Venice teemed with talent in other fields. Giambattista Tiepolo (1696-1770) was the undisputed master of large-scale decorative fresco painting, creating dazzling ceilings and wall paintings across Venice and Europe. Rosalba Carriera (1675-1757) achieved international fame for her exquisite pastel portraits. Pietro Longhi (1701-1785) chronicled the intimate social rituals and daily life of the Venetian aristocracy and bourgeoisie in his charming genre scenes. History painters like Sebastiano Ricci (1659-1734) and his nephew Marco Ricci (1676-1730), who also painted landscapes and caprices, contributed to the city's artistic richness. Figures like the collector and connoisseur Anton Maria Zanetti (1689-1767) played crucial roles as patrons and tastemakers within this vibrant milieu. Richter operated within this complex network of artists, patrons, and dealers.

Maturity and Artistic Independence

The mid-1730s are cited as the period when Johann Richter fully developed his mature and independent artistic style. This suggests a phase where he moved beyond the more direct influence of Luca Carlevaris, whose own activity was winding down (Carlevaris died in 1730). By this time, Canaletto was already the dominant figure in the veduta market. Richter's maturation involved forging his own path, perhaps finding a balance between the detailed documentation of Carlevaris and the atmospheric brilliance that Canaletto was perfecting.

His "unique artistic language" likely involved subtle distinctions in handling light, color, composition, and the depiction of figures. Perhaps his Northern European background subtly informed his perception of Venetian light or his approach to detail. His focus on both famous landmarks and "lesser-known spots" might also indicate a desire to offer something different from the standard repertoire, exploring the city more widely. This period of maturity represents the culmination of his artistic journey, where he confidently asserted his own vision within the competitive field of Venetian view painting. His works from this era are considered his most accomplished, showcasing his refined technique and personal interpretation of the Venetian scene.

Legacy and Influence: A Swedish Eye on Venice

Johann Richter occupies a specific place in the history of 18th-century Venetian painting. While perhaps not achieving the towering fame of Canaletto or the later poetic renown of Guardi, he was a skilled and respected practitioner of the veduta genre. His Swedish origins make him a notable example of the international artists drawn to Venice, contributing to the cosmopolitan nature of its art world. He successfully absorbed the techniques and conventions of Venetian view painting while developing his own recognizable style.

His influence on subsequent painters might be subtle compared to the impact of Canaletto, but his works contributed to the overall popularity and development of the veduta. He provided high-quality views for the Grand Tour market, helping to disseminate the image of Venice across Europe. His paintings serve as valuable historical documents, capturing the appearance of the city and the life of its inhabitants in the first half of the 18th century. The mention that his work potentially influenced later artists like Canaletto or "Ferrari" (perhaps referring to Guardi or another contemporary) suggests his art was recognized and possibly emulated by his peers, although Canaletto's primary influences are usually traced elsewhere. Richter's legacy lies in his consistent production of attractive, well-crafted vedute that combined accuracy with a gentle, poetic atmosphere, offering a distinct perspective on the enduring magic of Venice.

Conclusion: Remembering Johann Richter

Johann Richter stands as a testament to the magnetic pull of Venice on artists from across Europe. Arriving from Sweden, he embraced the city's signature genre, the veduta, and became a proficient chronicler of its unique beauty. Active from the late 17th century until his death in 1745, he bridged the era of the genre's founder, Luca Carlevaris, and its most famous exponent, Canaletto. While details of his life remain somewhat elusive, his paintings speak for themselves, offering meticulously observed yet atmospherically rendered views of Venice's architecture, waterways, and daily life.

His work, including representative sets like the "Four Views of Venice," showcases a mature style characterized by careful composition, lively color, sensitivity to light, and an integration of human activity within the urban landscape. As a Swedish painter who mastered a quintessentially Venetian art form, Johann Richter contributed his unique voice to the visual celebration of La Serenissima, leaving behind a body of work that continues to offer valuable insights into the appearance and spirit of Venice during its final century as an independent Republic. He remains an important figure for understanding the full breadth and depth of the Venetian veduta tradition.