Apollonio Domenichini, an artist whose life and work are intrinsically linked to the luminous city of Venice, remains a figure of considerable interest, yet one shrouded in a degree of historical ambiguity. Active primarily during the mid-18th century, he carved a niche for himself as a painter of vedute, or highly detailed, usually large-scale cityscape paintings, a genre that flourished in Venice, catering to the desires of Grand Tourists eager to take home a memento of the Serenissima's splendors. His works, characterized by a distinctive cool palette and meticulous attention to architectural detail, offer a captivating window into the daily life and celebrated vistas of 18th-century Venice.

It is crucial at the outset to address a point of potential confusion. The art historical record features another prominent artist named Domenichino, specifically Domenico Zampieri (1581–1641), a leading figure of the Bolognese School and a master of Baroque classicism. The information provided in the initial query included birth and death dates (October 21, 1581 – April 6, 1641) that pertain to this earlier Domenichino, not to the Venetian vedutista Apollonio Domenichini. This article will focus on Apollonio Domenichini, the 18th-century Venetian painter, while also acknowledging the biographical details mistakenly attributed to him, placing them in their correct context later.

The Emergence of an Identity: The "Master of the Langmatt Foundation"

For a considerable time, the artist we now know as Apollonio Domenichini was identified by a provisional name: the "Master of the Langmatt Foundation." This appellation arose from a significant group of Venetian views held in the collection of the Langmatt Foundation in Baden, Switzerland. These paintings, displaying a consistent and recognizable style, clearly originated from the same hand, but the artist's precise identity remained elusive.

The breakthrough in identifying this anonymous master came through the diligent research of art historians, notably Dario Succi. A key piece of evidence emerged from correspondence between the Venetian art dealer Giovanni Maria Sasso and the English diplomat and collector John Strange, a prominent figure in Venice during the latter half of the 18th century. In these letters, the name "Apollonio Domenichini" was mentioned in connection with the type of Venetian views that matched the style of the Langmatt paintings. This archival discovery provided the crucial link, allowing scholars to attribute the works of the "Master of the Langmatt Foundation" to Apollonio Domenichini.

This process of identification highlights a common challenge in art history, particularly for artists who may not have achieved the superstar status of contemporaries like Canaletto or Guardi, but who nonetheless made significant contributions to their respective genres. The meticulous work of sifting through archives, letters, and guild records is often essential to reconstructing the careers of such figures.

Life and Artistic Milieu in 18th-Century Venice

Details about Apollonio Domenichini's personal life remain relatively scarce, a common situation for many artists of his time who were not extensively chronicled by biographers like Giorgio Vasari in earlier centuries or who did not leave behind copious personal papers. However, we can place his activity firmly within the vibrant artistic context of 18th-century Venice.

It is generally accepted that Domenichini was active as a painter from approximately 1740 to 1770. A significant marker in his career is his documented membership in the Venetian Painters' Guild, the Fraglia de’ Pittori. Records indicate that he was enrolled in the guild in 1757. Membership in the Fraglia was important for professional artists in Venice, providing a degree of official recognition and regulating their practice. It suggests that by this point, Domenichini had established himself as a practicing artist within the city.

The Venice in which Domenichini worked was a city at the peak of its cultural allure, even as its political and economic power was waning. It was a magnet for travelers from across Europe, particularly from Britain, undertaking the Grand Tour. This influx of wealthy, educated tourists created a strong market for souvenirs, and Venetian view paintings were among the most prized. Artists like Domenichini catered to this demand, producing works that captured the unique beauty and atmosphere of the city.

Artistic Style, Influences, and Techniques

Apollonio Domenichini's artistic style is quite distinctive within the broader school of Venetian vedutisti. His paintings are often characterized by a cool, silvery light and a palette that frequently emphasizes blues, greens, and greys. This contrasts with the warmer, sunnier tones often found in the works of some of his contemporaries. His rendering of architecture is precise and detailed, demonstrating a keen observational skill and an understanding of perspective. The figures populating his scenes are typically small and somewhat stylized, serving to animate the urban landscapes rather than being the primary focus.

Several art historians have suggested potential influences on Domenichini's style. He may have been a pupil of, or at least significantly influenced by, Luca Carlevaris (1663–1730). Carlevaris is widely considered one of the pioneers of Venetian veduta painting, establishing many of the compositional formulas and thematic concerns that would be developed by later artists. His meticulous approach to architectural rendering and his organization of complex urban scenes could well have provided a model for Domenichini.

Another artist often cited as a possible influence is Michele Marieschi (1710–1743). Marieschi's vedute are known for their dynamic perspectives, dramatic lighting, and somewhat more painterly touch compared to the crystalline clarity of Canaletto. While Domenichini's style is generally more restrained than Marieschi's, there might be shared sensibilities in their approach to capturing the atmospheric qualities of Venice.

The towering figure of Giovanni Antonio Canal, better known as Canaletto (1697–1768), inevitably looms large in any discussion of 18th-century Venetian view painting. While it's not clear if Domenichini had any direct apprenticeship with Canaletto, the latter's immense success and widespread influence would have been impossible to ignore. Some scholars suggest that Domenichini might have found opportunities to develop his own market, particularly during periods when Canaletto was away from Venice, such as his extended stay in England (1746–1756). Domenichini’s works, while sharing the precision of Canaletto, often possess a more tranquil, almost melancholic mood, distinct from Canaletto's often brighter and more bustling depictions.

Domenichini's technique involved careful underdrawing and a methodical application of paint to achieve the smooth surfaces and fine detail evident in his works. His ability to capture the reflective qualities of water and the varied textures of stone and brick contributed significantly to the verisimilitude of his views.

Key Themes and Celebrated Subjects

Like other vedutisti, Apollonio Domenichini focused on the iconic landmarks and celebrated vistas of Venice. His repertoire included many of

the scenes that were most popular with Grand Tourists and local patrons alike.

The Grand Canal was a recurring subject, depicted from various viewpoints and featuring its procession of palaces, churches, and bustling water traffic. One of his most recognized works is The Grand Canal and the Basilica of Santa Maria della Salute. This painting showcases his skill in rendering complex architecture and capturing the interplay of light on water, with the majestic dome of the Salute church dominating the composition. Another significant work is A View of the Grand Canal with the Rialto Bridge, capturing the commercial heart of the city with its famous bridge teeming with activity.

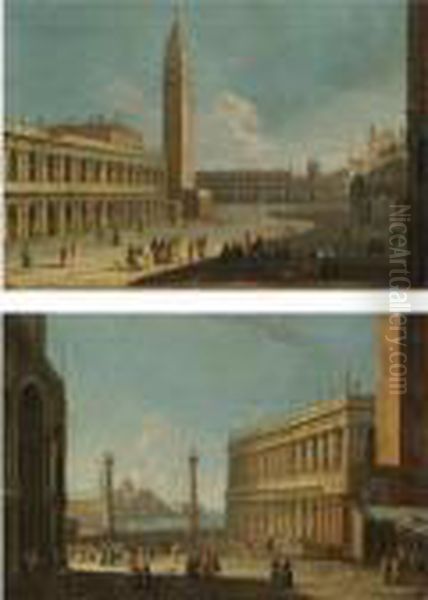

Piazza San Marco, the ceremonial and social heart of Venice, was another favorite subject. Domenichini painted numerous views of the Piazza, often looking towards the Basilica di San Marco and the Campanile. These paintings frequently include depictions of civic ceremonies, religious festivals, or simply the daily congregation of Venetians and visitors in this grand public space. Examples include A View of Piazza San Marco Looking Towards the Basilica and the Campanile and variations depicting the square on specific occasions like Ascension Day, a major Venetian festival involving the "Marriage of the Sea" ceremony.

Beyond these major landmarks, Domenichini also depicted other notable locations. A View of San Geremia and the entrance to the Cannaregio captures a less central but equally picturesque part of the city, showcasing the Church of San Geremia and the important Cannaregio Canal. Similarly, A view of the Grand Canal looking North-East with the Churches of Santa Lucia and the Scalzi (the Church of Santa Lucia was later demolished to make way for the railway station) demonstrates his interest in varied perspectives and the architectural fabric of the entire city.

His works often feature a strong sense of order and clarity, with carefully constructed perspectives that draw the viewer into the scene. The inclusion of numerous small figures engaged in various activities adds life and narrative interest to his architectural settings, providing a glimpse into the social fabric of 18th-century Venice.

Representative Works: A Closer Look

Apollonio Domenichini's oeuvre, while not as vast as that of Canaletto or Guardi, includes a number of significant paintings that exemplify his style and contribution to the veduta tradition.

_The Grand Canal and the Basilica of Santa Maria della Salute_: This is perhaps one of his most iconic compositions. It typically shows the majestic Baroque church from across the Grand Canal, often with gondolas and other boats in the foreground. Domenichini's characteristic cool light and meticulous rendering of the Salute's intricate architectural details are prominent. The play of light on the water and the subtle gradations of tone in the sky showcase his technical skill.

_A View of Piazza San Marco Looking Towards the Basilica and the Campanile_: A classic veduta subject, Domenichini’s interpretations of Piazza San Marco highlight his ability to manage complex perspectives and large numbers of figures. He captures the grandeur of the square, with the ornate façade of the Basilica and the towering Campanile providing strong focal points. The depiction of the Procuratie buildings lining the square demonstrates his attention to architectural accuracy.

_A View of Piazza San Marco on Ascension Day_: This subject allowed Domenichini to depict one of Venice's most important public spectacles. The scene would be enlivened with crowds, ceremonial barges (like the Bucintoro, the Doge's state barge), and festive decorations, offering a vibrant tableau of Venetian life. His cool palette would lend a unique atmosphere to such celebratory scenes.

_View of the Grand Canal with the Rialto Bridge_: The Rialto Bridge, a hub of commerce and activity, was another essential subject for any vedutista. Domenichini’s paintings of this area would capture the bridge itself, the bustling markets along the Riva del Vin and Riva del Ferro, and the varied boat traffic on the canal.

_View of San Geremia and the entrance to the Cannaregio_: This work demonstrates Domenichini's interest in depicting less central, yet still important, areas of Venice. The Church of San Geremia, with its distinctive campanile, and the wide entrance to the Cannaregio Canal offer a different perspective on the city's waterways and architecture.

_A view of the Grand Canal looking North-East with the Churches of Santa Lucia and the Scalzi_: This composition provides a view up the Grand Canal, featuring the now-demolished Church of Santa Lucia and the prominent Baroque façade of the Church of the Scalzi (Santa Maria di Nazareth). Such views highlight the rich architectural tapestry along Venice's main waterway.

These works, and others attributed to him, consistently display his hallmark cool tonalities, precise draftsmanship, and an ability to evoke the unique atmosphere of Venice. They were highly sought after by collectors and Grand Tourists, serving as enduring records of the city's beauty.

Contemporaries and the Venetian Art Scene

Apollonio Domenichini worked during a golden age of Venetian painting. The city was teeming with artistic talent across various genres. Understanding his place requires acknowledging the broader artistic landscape.

In the realm of veduta painting, besides the aforementioned Luca Carlevaris, Michele Marieschi, and Canaletto, another major figure was Francesco Guardi (1712–1793). Guardi’s style, particularly in his later works, was quite different from Domenichini's. Guardi favored a more painterly, atmospheric approach, with flickering brushwork (pittura di tocco) and a more romantic, sometimes melancholic, interpretation of Venice. His works often emphasize the ephemeral qualities of light and atmosphere over precise topographical accuracy. Bernardo Bellotto (1721–1780), Canaletto's nephew, also achieved great fame as a vedutista, though much of his career was spent outside Venice, in cities like Dresden, Vienna, and Warsaw, where he applied his uncle's meticulous style to new urban landscapes.

Beyond view painting, Venice was a center for other artistic expressions. Giovanni Battista Tiepolo (1696–1770) was the preeminent master of large-scale decorative frescoes and oil paintings, his works characterized by airy compositions, luminous colors, and dynamic figures. His son, Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo (1727–1804), also became a distinguished painter, known for his genre scenes and frescoes.

Rosalba Carriera (1673–1757) was a celebrated portraitist, particularly renowned for her delicate and insightful pastel portraits, which were highly sought after by an international clientele. Giovanni Battista Piazzetta (1683–1754) was another leading figure, known for his dramatic religious and genre paintings, as well as his expressive drawings.

Pietro Longhi (1701–1785) specialized in small-scale genre scenes, offering charming and often gently satirical glimpses into the daily life and social customs of the Venetian aristocracy and bourgeoisie. Landscape painting also flourished, with artists like Giuseppe Zais (1709–1781) and Francesco Zuccarelli (1702–1788) producing idyllic pastoral scenes that were popular with collectors.

This rich and diverse artistic environment provided both competition and stimulus for artists like Apollonio Domenichini. While he specialized in a particular genre, he was part of a broader cultural phenomenon that made Venice one of Europe's leading artistic capitals in the 18th century. His adherence to a clear, detailed style distinguished him from the more painterly approaches of some contemporaries like Guardi, and his cool palette offered a different sensibility than the often sun-drenched views of Canaletto.

The "Other" Domenichino: A Necessary Clarification of Identity

As mentioned earlier, the initial query contained biographical information—birth on October 21, 1581, and death on April 6, 1641—that belongs not to Apollonio Domenichini, the Venetian vedutista, but to Domenico Zampieri, universally known in art history as Domenichino. This earlier artist was a pivotal figure of the Italian Baroque, working primarily in Rome and Naples, and his style and subject matter are vastly different from those of Apollonio.

Domenico Zampieri was born in Bologna and was a prominent pupil of the Carracci family, particularly Ludovico Carracci. He later moved to Rome, where he became one of the leading exponents of classical idealism in painting, following in the tradition of Raphael and Annibale Carracci. His major works include frescoes in the Abbey of Grottaferrata, Sant'Andrea della Valle (the pendentives and apse depicting the life of St. Andrew), and San Luigi dei Francesi (Cappella di Santa Cecilia) in Rome. He also painted important altarpieces, such as The Last Communion of Saint Jerome (Pinacoteca Vaticana), a work that was highly praised for its emotional intensity and classical composition.

Anecdotes associated with this Domenichino include his intense working methods. It is said that Annibale Carracci, upon observing the young Domenichino's diligent studies, referred to him as the "ox" due to his laborious nature, predicting that this "ox" would one day "plow fertile ground." Another story, perhaps apocryphal but illustrative of the artistic rivalries of the time, involves accusations of plagiarism. Giovanni Lanfranco, a contemporary and rival, accused Domenichino of copying his Last Communion of Saint Jerome from an earlier altarpiece by Agostino Carracci. While the compositions share similarities, Domenichino's work is generally considered a more profound and original interpretation.

Domenichino also worked for Cardinal Pietro Aldobrandini, creating a series of mythological landscape frescoes, including scenes from the life of Apollo, in the Villa Aldobrandini in Frascati. He was known for his meticulous draftsmanship and his ability to convey deep emotion through gesture and expression. His contemporaries included other Bolognese-trained artists like Guido Reni and Francesco Albani, with whom he sometimes collaborated or competed. His later career in Naples was marked by intense rivalry and alleged persecution by local artists, contributing to the stress that some believe hastened his death in 1641.

It is clear that this Domenichino (Domenico Zampieri) is a distinct artistic personality from Apollonio Domenichini. The confusion likely arises from the similarity in names. Apollonio, the 18th-century Venetian, focused on the precise depiction of his native city, contributing to the veduta genre, while Domenico, the 17th-century Bolognese-Roman master, was a key figure in the development of Baroque classicism, excelling in religious and mythological narratives.

Legacy and Modern Reception

Apollonio Domenichini's legacy is primarily tied to his contribution to the genre of Venetian veduta painting. While he may not have achieved the international fame of Canaletto or the poetic renown of Guardi, his works are valued for their meticulous detail, distinctive cool atmosphere, and their faithful recording of 18th-century Venice.

His paintings continue to be appreciated by collectors and museums. The identification of his hand, particularly through the research connecting him to the "Master of the Langmatt Foundation," has brought greater clarity to his oeuvre and allowed for a more focused appreciation of his specific artistic qualities. His works serve as important historical documents, offering insights into the architecture, customs, and daily life of Venice during its last century as an independent republic.

For art historians, Domenichini represents an interesting case study of an artist who, while working within the established conventions of a popular genre, managed to develop a recognizable personal style. His paintings demonstrate the high level of technical skill and artistic sophistication that characterized Venetian painting in the 18th century, even among artists who were not in the absolute first rank of fame.

His views of Venice, with their serene light and precise rendering, offer a particular vision of the city – one that is both elegant and slightly reserved. They capture the enduring allure of Venice, a city that has fascinated artists and travelers for centuries. In the broader narrative of European art, Apollonio Domenichini stands as a skilled practitioner of a uniquely Venetian art form, contributing to the rich tapestry of 18th-century visual culture.

Conclusion

Apollonio Domenichini, the 18th-century Venetian vedutista, remains a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the history of art. His meticulously detailed and atmospherically cool depictions of Venice provide invaluable visual records of the city during its golden age of tourism and cultural splendor. Working in the shadow of giants like Canaletto, Domenichini nonetheless forged a distinct artistic identity, characterized by a cool palette, precise draftsmanship, and a tranquil, observant eye. His enrollment in the Fraglia de’ Pittori in 1757 attests to his professional standing in the vibrant Venetian art world.

Through the patient work of art historical scholarship, his identity has been more firmly established, distinguishing him from the earlier Baroque master Domenico Zampieri (Domenichino) and associating him definitively with the body of work previously attributed to the "Master of the Langmatt Foundation." His paintings of the Grand Canal, Piazza San Marco, and other Venetian landmarks continue to charm and inform, offering a timeless glimpse into the Serenissima. Apollonio Domenichini's contribution enriches our understanding of the veduta genre and the diverse artistic talents that flourished in 18th-century Venice, a city whose beauty he so skillfully captured for posterity.