The annals of art history are filled with celebrated names, artists whose lives and works have been meticulously documented and studied. Yet, alongside these luminaries exist figures shrouded in mystery, known only through a distinctive body of work attributed to an anonymous hand. Among these enigmatic creators is the artist designated as the "Master of the Langmatt Foundation Views," a painter active in 18th-century Venice whose identity remains uncertain, yet whose artistic contributions offer a valuable window into the world of Venetian veduta painting.

This artist owes his designation to a remarkable series of thirteen Venetian view paintings housed in the collection of the Museum Langmatt in Baden, Switzerland. These works, consistent in style and execution, were recognized in the 20th century as the product of a single, skilled individual. Despite extensive art historical research, a definitive name has yet to be attached to these canvases, leaving us with a compelling artistic personality defined solely by the visual evidence of his craft. The investigation into his identity, style, and place within the bustling artistic milieu of 18th-century Venice reveals a fascinating story of artistic production, patronage, and the enduring allure of the Venetian cityscape.

The Langmatt Foundation and the Emergence of a Master

The Museum Langmatt, established in the former residence of Sidney and Jenny Brown-Sulzer, stands as a significant repository of late 19th and early 20th-century art, particularly French Impressionism. Sidney Brown, a technical director and later joint owner of the Brown, Boveri & Cie (BBC) engineering company, and his wife Jenny, amassed a distinguished collection featuring works by masters such as Paul Cézanne, Edgar Degas, Paul Gauguin, Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and Alfred Sisley. Their collecting journey began around 1908 and continued for several decades, reflecting a deep engagement with the art of their time.

However, alongside these celebrated Impressionist and Post-Impressionist works, the Browns also acquired a coherent group of thirteen Venetian vedute, or view paintings. These canvases, depicting iconic scenes of Venice with a consistent stylistic approach, initially entered the collection without a firm attribution to a known artist. It was only through later scholarly examination, likely in the mid-to-late 20th century, that art historians recognized the unifying hand behind these works, grouping them under the descriptive moniker "Master of the Langmatt Foundation Views." This act of connoisseurship highlighted the quality and distinctiveness of the paintings, elevating them from anonymous decorative pieces to the oeuvre of a recognizable, albeit unnamed, artistic personality.

The presence of these Venetian views within a collection primarily focused on French modernism is intriguing. It speaks perhaps to the enduring appeal of Venice as a subject, or maybe to a particular aesthetic appreciation the Browns had for this specific set of paintings. Regardless of the initial collecting motive, the Langmatt Foundation became the crucial anchor for this artist's identity, preserving the core body of work through which his style and significance can be assessed. The museum, opened to the public following Jenny Brown's death according to the couple's wishes formalized in a foundation established in 1988, thus serves not only as a home for Impressionist masterpieces but also as the primary custodian of this anonymous Venetian master's legacy.

Artistic Style and Venetian Subject Matter

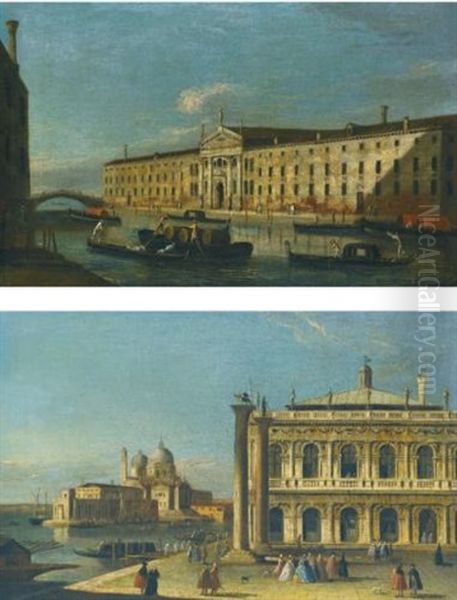

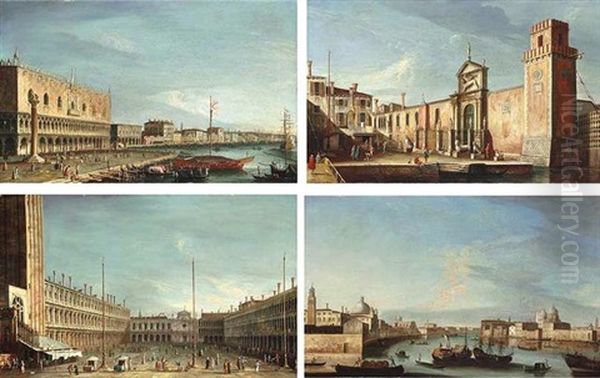

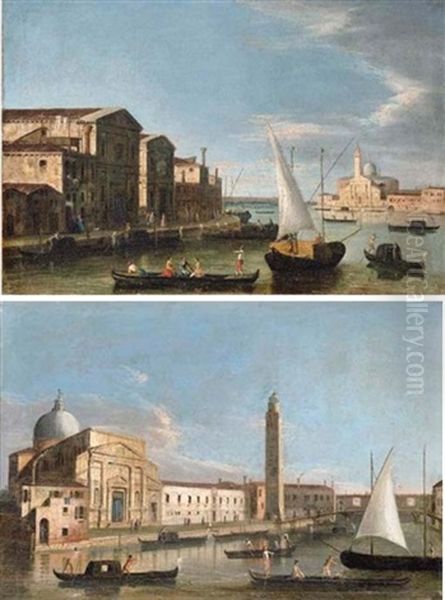

The Master of the Langmatt Foundation Views worked firmly within the tradition of the Venetian veduta, a genre that flourished in the 18th century, catering largely to the tastes of Grand Tourists seeking sophisticated souvenirs of their travels. His style is characterized by a careful attention to architectural detail, a clear and luminous palette, and a competent handling of perspective and light, typical of the mid-century Venetian school. While perhaps not reaching the sublime atmospheric effects of Canaletto at his peak or the later, more fluid dynamism of Francesco Guardi, the Langmatt Master demonstrates considerable skill in rendering the complex topography and vibrant life of Venice.

His paintings capture the quintessential Venetian scenes: bustling views of the Piazza San Marco, often including the Campanile (bell tower) and the Doge's Palace; depictions of the Grand Canal with its gondolas and flanking palazzi; and views of other well-known churches and campi (squares). The figures populating these scenes, known as 'staffage', are typically small but lively, adding touches of local color and narrative interest – gondoliers maneuvering their craft, elegantly dressed citizens conversing, merchants tending to their affairs. This inclusion of daily life, set against the backdrop of magnificent architecture and shimmering water, was a hallmark of the veduta genre.

The overall impression is one of clarity, order, and a certain picturesque charm. The light is often bright and evenly distributed, typical of Venetian painting influenced by the city's unique aquatic reflections. The brushwork appears controlled and precise, particularly in the rendering of architectural elements, ensuring topographical accuracy which was highly valued by patrons. While adhering to the established conventions of veduta painting, the Langmatt Master's work possesses a recognizable quality, a specific 'handwriting' in the way details are rendered or compositions are structured, which allowed art historians to group the Langmatt paintings together.

Representative Works: The Langmatt Vedute

The core of the Master's known output resides in the thirteen paintings at the Museum Langmatt. While specific titles may vary, the subjects are characteristic of the Venetian view painting tradition. Prominent among these are likely multiple perspectives of the heart of Venice: the Piazza San Marco and the Piazzetta. Works titled along the lines of Piazza San Marco Looking Towards the Basilica or The Piazzetta Looking Towards Santa Maria della Salute would be typical. These compositions allowed the artist to showcase iconic landmarks like St. Mark's Basilica, the Doge's Palace, the Campanile, the Procuratie Nuove and Vecchie, and the Biblioteca Marciana.

One specific point of interest arises from depictions of the Campanile of St. Mark's. Art historical analysis, potentially based on details like the state of the Campanile's loggia or surrounding structures, has suggested that at least one of the St. Mark's Square views must have been completed after 1755. This provides a valuable chronological marker, placing the artist's activity firmly in the mid-18th century or later. Such dating relies on comparing the painted view with known architectural changes in Venice, a common method used for dating vedute.

Other works in the series likely include views along the Grand Canal, perhaps featuring the Rialto Bridge or specific palaces, and possibly depictions of important churches like Santa Maria della Salute or San Giorgio Maggiore. Each painting would contribute to a composite portrait of Venice, capturing its architectural grandeur, aquatic environment, and bustling social life. The significance of the Langmatt series lies not just in individual works but in the group itself, offering a coherent and sustained vision of Venice through the eyes of this particular artist. They stand as his primary testament, the benchmark against which any newly attributed works must be compared.

The Venetian Context: Masters and Influences

The 18th century, or Settecento, was the golden age of Venetian painting, particularly for view painting. The Master of the Langmatt Foundation Views operated within a rich and competitive artistic environment dominated by several key figures and influenced by established traditions. Understanding this context is crucial to appreciating his work and the quest to identify him. The demand for vedute was immense, fueled by the aforementioned Grand Tour, where wealthy Northern Europeans, especially the British, visited Italy to complete their education, acquiring art and artifacts as mementos.

The foundational figure in 18th-century Venetian veduta painting was Luca Carlevarijs (1663-1730). He essentially established the genre's popularity in Venice, moving away from earlier, more fantastical caprices towards topographically accurate depictions of the city, often featuring ceremonial events. His detailed style and compositional formats laid the groundwork for subsequent artists. It is plausible, as some sources suggest, that the Langmatt Master might have had connections, perhaps indirect, to Carlevarijs's workshop or circle, or at least absorbed his influence.

Towering over the entire field was Giovanni Antonio Canal, known as Canaletto (1697-1768). His luminous, precise, and often dramatically composed views set the standard for excellence. Canaletto's international fame, particularly in England through his association with the agent Joseph Smith, meant his style was widely imitated. Any Venetian vedutista working in the mid-18th century, including the Langmatt Master, would have been acutely aware of Canaletto's work and likely responded to it, either through emulation or by seeking a distinct niche.

A close contemporary and sometimes rival of Canaletto was Michele Marieschi (1710-1743). His career was shorter, but his style offered a slightly different flavor, often characterized by more dynamic perspectives, sparkling highlights, and a somewhat looser, more painterly touch than Canaletto's early work. The fact that a work once attributed to the Langmatt Master was later identified as Marieschi's highlights the stylistic similarities and potential overlaps among these artists, making attributions complex.

Canaletto's nephew, Bernardo Bellotto (c. 1721-1780), also became a major vedutista. While trained by Canaletto and initially working in a similar style, Bellotto developed his own distinct manner, often featuring cooler light, sharper contrasts, and meticulous detail, which he applied to views not only of Venice but also Dresden, Vienna, and Warsaw, where he spent much of his career. His work demonstrates the dissemination of the Venetian veduta style across Europe.

Representing a later phase of the genre is Francesco Guardi (1712-1793). While he also painted topographically recognizable views, Guardi increasingly moved towards a more atmospheric and evocative style. His brushwork became looser, his light more flickering, capturing the ephemeral qualities of the Venetian lagoon and sky, often imbued with a sense of melancholy or romanticism. His approach contrasts with the crystalline clarity often sought by Canaletto and his followers, including likely the Langmatt Master. Francesco's brother, Gianantonio Guardi (1699-1760), was primarily a figure painter, but their family workshop was a significant artistic force. Francesco's son, Giacomo Guardi (1764-1835), continued painting Venetian views in his father's style well into the 19th century.

Other figures populated the Venetian art scene. Giuseppe Zais (1709-1784) was known more for pastoral landscapes but also painted some Venetian scenes. Antonio Joli (c. 1700-1777), though Venetian-trained, spent much of his career working in other cities, including London and Naples, demonstrating the mobility of artists and styles. Earlier influences like the Dutch painter Gaspar van Wittel (1653-1736), known in Italy as Vanvitelli, who worked primarily in Rome and Naples, were also important in developing the tradition of topographical view painting in Italy, which Venetian artists then perfected. Even Roman view painters like Giovanni Paolo Panini (1691-1765), known for his views of Roman ruins and festivals, were part of the broader Italian veduta phenomenon. The Langmatt Master worked amidst this constellation of talent, absorbing influences and developing his own particular approach to capturing the Venetian spectacle.

The Quest for Identity: Apollonio Domenichini and Other Possibilities

Given the anonymity of the Master of the Langmatt Foundation Views, art historians have naturally sought to connect his work to named artists active in Venice during the relevant period. The most compelling candidate proposed is Apollonio Domenichini, sometimes referred to as the "Master of the Fondazione Langmatt" in scholarly literature discussing his potential authorship. Domenichini was active primarily between the 1740s and 1770s, a timeframe consistent with the style and potential dating (post-1755 for at least one work) of the Langmatt paintings.

The primary evidence linking Domenichini to the Langmatt Master is stylistic similarity. Art historians familiar with Domenichini's attributed works note correspondences in compositional structure, the handling of architectural details, the characteristic rendering of figures (staffage), and the overall palette and application of paint. Domenichini is known to have been a follower or imitator of Canaletto, and possibly influenced by Luca Carlevarijs as well, placing him squarely within the mainstream of Venetian veduta production. His works often depict the standard repertoire of Venetian views, aligning perfectly with the subjects found in the Langmatt collection.

Further circumstantial evidence comes from Domenichini's association with the wider circle of Venetian view painters. Some sources suggest he was a follower of the vedute produced by the workshop or circle associated with a figure named Massimo Massini, indicating his participation in the active market for such paintings. If Domenichini was indeed the Langmatt Master, it would place the latter firmly within the orbit of Canaletto's influence, perhaps as a skilled secondary master catering to the consistent demand for Venetian souvenirs.

However, the identification remains tentative. No signed works by Domenichini have been definitively matched to the Langmatt series, nor has any documentary evidence emerged to confirm the connection. The attribution rests on connoisseurship – the discerning eye comparing stylistic traits. The confusion mentioned earlier, where a painting initially linked to the Langmatt Master was reattributed to Michele Marieschi, underscores the challenges in distinguishing between the hands of competent contemporaries working in similar styles.

Another name occasionally mentioned, possibly due to confusion in sources or alternative theories, is Francesco Albotto (or Alto). Albotto (1721-1757) was a pupil and collaborator of Marieschi, inheriting his workshop upon Marieschi's early death. While active in the correct period and genre, the stylistic connection to the Langmatt Master is generally considered less convincing than the link to Domenichini by most scholars specializing in the field. Until definitive proof emerges, Apollonio Domenichini remains the most plausible, yet unconfirmed, identity for the Master of the Langmatt Foundation Views.

Legacy and Significance

Though his name remains elusive, the Master of the Langmatt Foundation Views holds a distinct place in the history of 18th-century Venetian art. His work exemplifies the high level of skill and artistry achieved by painters operating alongside the most famous names like Canaletto and Guardi. He represents the depth and breadth of the veduta tradition, demonstrating that the market supported numerous talented artists specializing in this popular genre. His paintings are not mere copies but possess their own character and quality.

The thirteen works preserved at the Museum Langmatt constitute a significant and coherent group, offering a valuable resource for studying mid-18th-century Venetian view painting. They serve as important documents of the city's appearance at that time, capturing architectural details and the atmosphere of daily life before the fall of the Venetian Republic and the subsequent changes to the city. For art historians, the Langmatt Master presents a fascinating case study in attribution and connoisseurship, highlighting the process by which anonymous works are grouped and potentially identified based on stylistic analysis.

His legacy, therefore, is twofold. Artistically, he contributed a body of competent and appealing works to the rich tapestry of Venetian painting, capturing the enduring magic of the city. Historically, his anonymity reminds us of the many skilled artisans and artists whose names have been lost to time but whose works continue to enrich our understanding of past eras. The Master of the Langmatt Foundation Views stands as a testament to the vibrant artistic production of Settecento Venice and the enduring power of its cityscape to inspire artists and captivate viewers.

Conclusion: An Enduring Enigma, A Lasting Impression

The Master of the Langmatt Foundation Views remains an enigma, a name assigned out of necessity to a talented hand whose identity history has obscured. Yet, the paintings themselves speak with clarity and charm. They transport us to the bustling squares and shimmering canals of 18th-century Venice, rendered with a skill that commands respect. The potential identification with Apollonio Domenichini offers a tantalizing possibility, linking the Langmatt works more firmly to the known network of Venetian vedutisti influenced by Carlevarijs and Canaletto.

Regardless of whether his true name is ever definitively discovered, the Master of the Langmatt Foundation Views has secured his place through the quality of his work and its preservation in a significant collection. His paintings contribute to our appreciation of the Venetian veduta tradition, showcasing the widespread appeal and high standards of this genre during its golden age. They stand as beautiful objects in their own right and as valuable historical documents, ensuring that this anonymous master continues to make a lasting impression on all who encounter his vision of Venice. The mystery of his identity only adds another layer of fascination to his artistic legacy.