Giulio Rosati stands as a prominent figure in late 19th and early 20th-century Italian art, celebrated primarily for his captivating Orientalist paintings. Born in Rome in 1858 and passing away in the same city in 1917, Rosati dedicated his artistic career to depicting the vibrant, albeit often imagined, scenes of North Africa and the Middle East. Though he never personally set foot in the lands he so vividly portrayed, his work resonated deeply with European audiences, offering them a glimpse into exotic locales filled with bustling markets, nomadic horsemen, and richly decorated interiors. His mastery, particularly in watercolor, allowed him to create detailed, colorful, and atmospheric compositions that remain highly sought after by collectors today.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Rome

Giulio Rosati was born into a family with established roots in banking and the military. Eschewing the paths suggested by his family background, the young Rosati demonstrated a clear inclination towards the arts. He pursued formal artistic training in his native Rome, enrolling at the prestigious Accademia di San Luca. This institution provided him with a solid foundation in academic principles of drawing, composition, and painting.

During his time at the Accademia, Rosati studied under several respected artists who undoubtedly influenced his development. Among his teachers were Dario Querci, known for his historical and genre paintings, and Francesco Podesti, a significant figure in Italian Neoclassicism and Romanticism, renowned for large-scale historical and religious works. He also received instruction from the Spanish painter Luis Álvarez Catalá, who was active in Rome and known for his historical genre scenes, often characterized by meticulous detail and vibrant color, traits that would become hallmarks of Rosati's own style. This rigorous academic training equipped Rosati with the technical proficiency necessary to execute his later intricate works.

The Allure of the Orient: An Armchair Traveler's Vision

Rosati specialized almost exclusively in Orientalist subjects, focusing his artistic lens on the landscapes, people, and cultures of the Maghreb – regions like Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia – as well as other parts of the Middle East. What makes Rosati's dedication to this genre particularly fascinating is the well-documented fact that he never actually traveled to these places. His vision of the Orient was constructed entirely within the confines of his Roman studio.

To achieve the remarkable level of detail and perceived authenticity in his paintings, Rosati relied heavily on secondary sources. He was an avid collector of information and artifacts. Photographs, which were becoming increasingly available in the latter half of the 19th century, provided visual references for architecture, landscapes, and human figures. Engravings and illustrations from travel books offered further compositional ideas and details. Furthermore, his studio was likely filled with props – exotic textiles, intricately patterned carpets, Middle Eastern weapons, pottery, and other objects – which he could study firsthand and incorporate into his scenes. This method of "armchair Orientalism" was not unique to Rosati, but he practiced it with exceptional skill and dedication.

Mastery of Medium and Meticulous Detail

While occasionally working in oils, Giulio Rosati achieved his greatest renown for his works in watercolor. This medium, with its potential for luminosity and transparency, proved perfectly suited to his style. Watercolor allowed him to build up layers of vibrant color and capture minute details with precision, lending an immediacy and freshness to his scenes. His technical virtuosity in handling watercolor is evident in the delicate rendering of fabrics, the intricate patterns on tiles and carpets, and the play of light across different surfaces.

Rosati's paintings are characterized by their rich and harmonious color palettes. He employed bold hues to convey the bright sunlight of North Africa and the opulence of imagined interiors. His compositions are typically well-structured, often filled with multiple figures engaged in various activities, creating dynamic and engaging narratives. The level of detail is consistently high, extending from the facial expressions and gestures of his figures to the textures of their clothing, the ornamentation of their surroundings, and the specific items within a market stall or domestic setting. This meticulous attention to detail was crucial in creating a convincing illusion of reality for his European audience.

Recurring Themes and Narrative Scenes

Rosati's oeuvre explores several recurring themes common within the Orientalist genre, each rendered with his characteristic flair for color and detail. Scenes of bustling marketplaces are frequent, depicting merchants selling their wares – carpets, pottery, metalwork – amidst crowds of shoppers and onlookers. These paintings capture the energy and exoticism associated with Middle Eastern souks, filled with diverse characters and goods.

Arab horsemen are another signature subject for Rosati. Often depicted galloping across desert landscapes, sometimes engaged in mock battles or displays of skill known as "fantasias," these scenes convey a sense of dynamism, freedom, and martial prowess. The horses themselves are rendered with anatomical accuracy and energy, while the riders are adorned in flowing robes and elaborate weaponry.

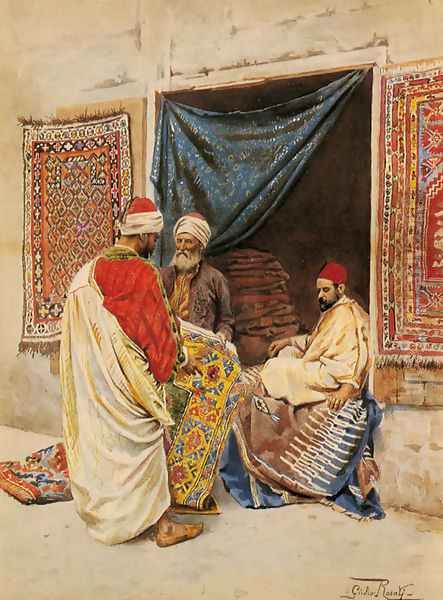

Quieter, more intimate scenes also feature prominently in his work. He often painted figures relaxing in sun-drenched courtyards, perhaps engaged in conversation or playing games like chess or backgammon (Tavli). These compositions allowed Rosati to showcase his skill in depicting architecture, decorative tilework, and the interplay of light and shadow in enclosed spaces. Scenes involving carpet merchants provided ample opportunity to display dazzling arrays of color and pattern, highlighting the luxurious textiles that were highly prized in Europe.

Spotlight on Signature Works

Several specific paintings exemplify Giulio Rosati's style and thematic concerns. The Arab Riders (also sometimes referred to as Two Cavalrymen or similar titles depicting horsemen) showcases his ability to capture movement and drama. Typically set against a vast desert backdrop, these works feature meticulously rendered horses and riders, conveying speed and a sense of untamed energy, appealing to the European fascination with Bedouin culture.

Backgammon Players in a Courtyard (or Chess Players, Giocatori di scacchi, The Game of Tavli) represents his skill in depicting scenes of daily life and leisure. These paintings often feature two or three men engrossed in a game, seated on carpets within an architecturally detailed courtyard. Rosati uses these settings to explore textures – stone, tile, fabric – and the effects of light, creating a tranquil yet engaging atmosphere. The focus on traditional games adds to the cultural specificity of the scene.

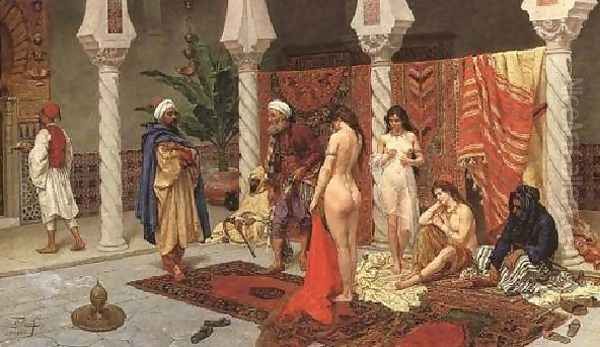

Choosing the Favorite delves into the popular, yet often problematic, Orientalist theme of the harem. While reflecting 19th-century European fantasies about secluded female spaces in the Islamic world, Rosati's treatment focuses on the rich environment, the elaborate costumes of the figures, and the narrative potential of the scene. Such works highlight the intricate detail he lavished on textiles, jewelry, and interior decoration, creating a vision of opulent sensuality.

The Carpet Merchant is another quintessential Rosati subject. These paintings are visual feasts of color and texture, centered around the display and sale of luxurious Oriental rugs. Rosati masterfully renders the intricate patterns and rich dyes of the carpets, often contrasting them with the simpler attire of the merchants and customers or the architectural setting of the marketplace. These works underscore the European fascination with Eastern craftsmanship. Similarly, Inspection of the New Arrivals often depicts merchants examining goods, allowing Rosati to showcase a variety of exotic objects and textiles.

His work titled Oriental Scene, exhibited at the Exposition de Belle Art in Paris in 1900, marked a rare instance of Rosati participating in a major public exhibition. This exposure likely contributed to his reputation as one of the leading Italian Orientalists of his time.

A Flourishing Career Beyond Exhibitions

Despite his evident skill and the growing popularity of his work, Giulio Rosati largely eschewed the traditional path of seeking recognition through official Salons and large public exhibitions. The 1900 Paris exhibition appears to have been an exception rather than the rule. Instead, he cultivated relationships with art dealers, primarily selling his paintings directly through them.

This strategy proved highly successful commercially. His detailed, colorful, and accessible depictions of the Orient found a ready market among European and American collectors. Tourists, in particular, were drawn to his works, which served as exotic souvenirs and reminders of real or imagined travels. The relatively small scale of many of his watercolors also made them suitable for domestic display. Rosati's consistent output and the popular appeal of his subject matter ensured a steady income and a reputation among connoisseurs of Orientalist art, even without frequent public showings.

Orientalism: A Wider Artistic Context

Giulio Rosati worked during the peak of Orientalism's popularity in European art. This movement, which gained momentum in the early 19th century with artists like Eugène Delacroix following his travels to North Africa, encompassed a wide range of styles and attitudes towards the East. It was fueled by Romanticism's fascination with the exotic, the expansion of European colonialism, increased travel and trade, and the dissemination of images through photography and print media.

French artists were particularly dominant in the field. Jean-Léon Gérôme became famous for his highly detailed, almost photographic depictions of Middle Eastern life, historical scenes, and architectural studies, often based on extensive travels. Others like Eugène Fromentin combined painting with travel writing, while Théodore Chassériau blended Romanticism with classical influences in his Orientalist works.

In Britain, artists like John Frederick Lewis, who lived in Cairo for years, produced incredibly detailed watercolors and oils of domestic life. David Roberts gained fame for his topographical views of Egypt and the Holy Land. Even the great J.M.W. Turner, known for his atmospheric landscapes, occasionally touched upon Oriental themes. The Spanish painter Mariano Fortuny brought a vibrant, sun-drenched palette to his scenes of Morocco. Austrian artist Rudolf Ernst specialized in meticulously rendered, often idealized, depictions of Islamic scholars, guards, and artisans in opulent interiors. American painters like Frederick Arthur Bridgman and John Singer Sargent also contributed significantly to the genre, the latter particularly with his Venetian scenes that sometimes incorporated North African elements or figures. Rosati's teachers, Francesco Podesti and Luis Álvarez Catalá, while not primarily Orientalists, worked within the broader academic and historical genre traditions that informed the movement.

Rosati's Niche in the Orientalist Pantheon

Within this diverse landscape, Giulio Rosati carved out his own distinct niche. Unlike Gérôme or Lewis, he was not concerned with ethnographic accuracy based on direct observation. His Orient was largely a construct, a picturesque stage for vibrant genre scenes. Unlike the grand scale of Delacroix's historical interpretations, Rosati generally preferred smaller, more intimate compositions, particularly suited to the watercolor medium he favored.

His emphasis on bright color, lively figure groups, and meticulous detail placed him among the more decorative and accessible Orientalist painters. While the French dominated the movement in terms of influence and the number of practitioners who actually traveled, Rosati became one of Italy's foremost exponents of Orientalism, alongside artists like Alberto Pasini, who, unlike Rosati, did travel extensively in the Middle East, and Stefano Ussi. Rosati's studio-based approach, relying on props and secondary sources, aligns him with artists like Rudolf Ernst, who also created highly detailed but often idealized visions of the East. His work provided a romanticized, easily digestible version of the Orient that perfectly met the demands of the late 19th-century art market.

Legacy and Critical Reception

Giulio Rosati enjoyed considerable success during his lifetime, and his works remain popular at auction today. His paintings are appreciated for their technical skill, vibrant colors, and charming depictions of exotic life, even if that life was filtered through a European imagination. His son, Alberto Rosati (active circa 1900), followed in his father's footsteps, also becoming an Orientalist painter, though his output was considerably smaller and less renowned than Giulio's.

In contemporary art history, Orientalism as a whole is often viewed through a critical lens, acknowledging its tendency towards stereotype, exoticization, and its complex relationship with European colonialism (as famously analyzed by Edward Said). Rosati's work, like that of many of his contemporaries, can be seen as participating in the creation of a Western fantasy of the East, sometimes emphasizing sensuality, indolence, or primitive splendor. However, his paintings are also valued as historical documents reflecting 19th-century European tastes and perceptions. Beyond critique, the sheer artistic skill, particularly his mastery of watercolor and his ability to create complex, detailed, and visually appealing compositions, continues to earn him admiration.

Conclusion: An Enduring Vision of the East

Giulio Rosati remains a significant figure in the history of Italian art and the broader Orientalist movement. As a master watercolorist, he brought the imagined scenes of North Africa and the Middle East to life with vibrant color and meticulous detail. Though he never witnessed firsthand the lands he painted, his ability to synthesize information from photographs, prints, and objects allowed him to create convincing and captivating visions that resonated strongly with his audience. His focus on lively genre scenes – markets, horsemen, games, merchants – offered a picturesque and romanticized glimpse into cultures perceived as exotic by Europeans. Commercially successful and technically proficient, Rosati crafted an enduring legacy as a painter who skillfully wove compelling fantasies of the Orient from the heart of his Roman studio. His work continues to enchant viewers with its decorative appeal and technical brilliance, securing his place as a key Italian contributor to the Orientalist tradition.