Giuseppe Maria Crespi, often known by his nickname "Lo Spagnuolo" (The Spaniard), stands as a significant figure in the transition from the high drama of the Italian Baroque to the more intimate observations of the 18th century. Born in Bologna on March 14, 1665, and passing away in the same city on July 16, 1747, Crespi carved a unique path, distinguished by his realistic depiction of everyday life, his masterful use of light and shadow, and a style that synthesized Baroque intensity with emerging Rococo sensibilities. His work left a lasting mark on Italian painting, particularly influencing the development of genre scenes.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Bologna

Crespi's artistic journey began in his native Bologna, a city with a rich artistic heritage, particularly known for the Carracci Academy and its influence on Baroque painting. His initial training was under Angelo Michele Toni, where he likely learned the fundamentals of drawing and painting. He further honed his skills in the bustling workshops of prominent Bolognese masters.

His education continued under Domenico Canuti, a respected painter known for his large-scale decorative works. Crespi also spent time in the studio of Carlo Cignani, a leading figure in late Bolognese classicism. During this period, he is known to have collaborated with Giovanni Antonio Burrini, another notable Bolognese painter. These formative experiences immersed Crespi in the prevailing artistic currents of Bologna, providing him with a solid foundation in technique and composition. However, Crespi possessed an independent spirit; it is noted that he eventually grew dissatisfied with Canuti's style, suggesting an early inclination towards forging his own artistic identity.

Development of a Unique Style: Influences and Innovation

While rooted in the Bolognese tradition, Crespi's artistic vision expanded through exposure to other Italian and European masters. A pivotal trip to Venice proved highly influential. There, he studied the works of the great Venetian masters, particularly Titian and Paolo Veronese. The Venetian emphasis on rich color, atmospheric effects, and dynamic compositions left a discernible impact on Crespi's own use of color and his ability to create visually striking scenes.

The dramatic use of light and shadow, or chiaroscuro, became a hallmark of Crespi's style. This aspect shows a clear debt to Caravaggio, whose revolutionary approach to light had transformed Italian painting a century earlier. Crespi adapted this technique, using strong contrasts not just for dramatic effect but also to model form and create a palpable sense of reality, even in humble settings.

Further influences came from diverse sources. Later in his career, the elegance of Guido Reni and the dynamic energy of Pietro da Cortona are said to have informed his work. He also reportedly drew inspiration from Flemish painting, particularly in the handling of religious subjects. Notably, the influence of the Dutch master Rembrandt, renowned for his mastery of light and psychological depth, is often cited, particularly regarding Crespi's sophisticated chiaroscuro and perhaps even his use of techniques similar to the camera obscura to achieve heightened realism.

Artistic Style: Realism, Emotion, and Technical Skill

Crespi's mature style is characterized by a fascinating blend of elements. He retained the dynamism and emotional intensity associated with the Baroque but tempered it with a growing interest in naturalism and the subtleties of human experience. His work often bridges the gap between the grand theatricality of the Baroque and the lighter, more intimate feel of the emerging Rococo style. Some observers have even noted qualities anticipating Impressionism in his quick, lively brushwork, his use of bright white highlights, and his often soft, harmonious color palettes.

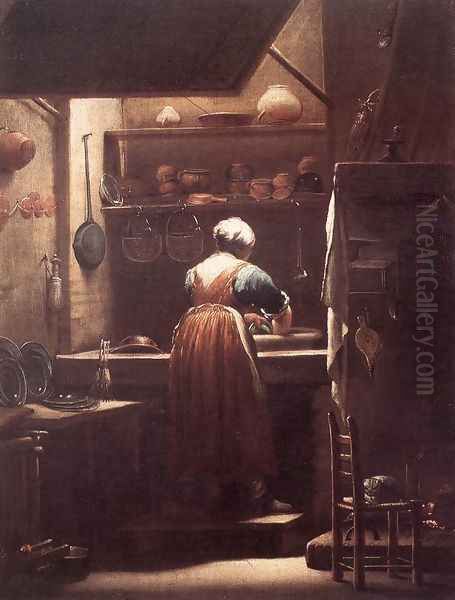

Realism was central to his approach. Crespi turned his keen eye towards the world around him, finding subjects not only in grand historical or religious narratives but also in the mundane activities of ordinary people. He depicted peasants, servants, and artisans with an honesty and empathy that was relatively uncommon for the time. His figures are not idealized types but individuals captured in moments of work, leisure, or quiet contemplation. This focus on genre scenes became one of his most significant contributions.

His technical skill was considerable. He masterfully employed chiaroscuro to create mood and focus attention. His brushwork could be both energetic and precise, adapting to the subject matter. Whether rendering the texture of rough fabric, the glint of light on metal, or the subtle expression on a face, Crespi demonstrated a remarkable command of his medium. He combined the Bolognese tradition of strong drawing with a Venetian sensitivity to color and light.

Major Works and Thematic Concerns

Crespi's oeuvre spans religious subjects, genre scenes, portraits, and still lifes, showcasing his versatility.

Religious Paintings: While renowned for genre scenes, Crespi was also a powerful religious painter. His most celebrated work in this vein is the series The Seven Sacraments, painted around 1712 for Cardinal Pietro Ottoboni. Considered a pinnacle of late Baroque religious art, this series depicts the sacraments not as distant celestial events but as solemn, human rituals taking place in dimly lit, atmospheric interiors. Crespi's innovative use of light and shadow imbues these scenes with profound spirituality and emotional weight. Other notable religious works include the Ecstasy of Saint Margaret of Cortona, the Massacre of the Innocents (painted for Ferdinando de' Medici), The Temptation of Saint Anthony, David (depicting the psalmist in deep concentration), The Crucifixion of Christ (noted for its dramatic intensity), and tender portrayals like The Virgin and Child. In all these works, he brought a sense of psychological realism to sacred narratives.

Genre Scenes: Crespi truly excelled in the depiction of everyday life. Works like The Washerwoman, The Scullery Maid, The Flea Seeker (or The Flea), and The Dice Players exemplify his contribution to genre painting. These paintings offer intimate glimpses into the lives of common people. The Flea Seeker, for instance, portrays a woman engrossed in a mundane, intimate task, rendered with unvarnished realism and a touch of quiet dignity. Crespi observed details meticulously, capturing the textures of simple interiors and the unposed attitudes of his subjects. These works reveal his deep interest in human activity and his sympathy for the less privileged strata of society.

Portraiture and Still Life: Crespi also undertook portrait commissions, particularly for Bolognese noble families, demonstrating his ability to capture likeness and character. Although less numerous, his still lifes, such as the Still Life of Game Birds, show the same careful observation and skillful handling of light and texture found in his other works.

Career Highlights, Patronage, and Later Life

Crespi's talent gained recognition beyond Bologna. Around 1708, he traveled to Florence, where he worked for the Grand Prince Ferdinando de' Medici, a significant patron of the arts. His paintings for the Prince, including the Massacre of the Innocents and The Temptation of Saint Anthony, significantly enhanced his reputation. Despite opportunities elsewhere, including a reported invitation to work in Rome (possibly extended by his former teacher Cignani, though sources suggest Crespi declined), he remained primarily based in Bologna throughout his long career.

He maintained connections with important patrons and collectors, both within Bologna and further afield, like the aforementioned Ferdinando de' Medici and Cardinal Ottoboni in Rome. His ability to navigate these relationships was crucial for securing commissions and ensuring his livelihood.

In his later years, Crespi established his own successful workshop or gallery in Bologna. He became an influential teacher, passing on his skills and artistic philosophy to a new generation of painters. His dedication to his craft continued until his death in 1747 at the advanced age of 82.

Legacy and Influence on Subsequent Artists

Giuseppe Maria Crespi holds an important place in Italian art history. He was a pivotal figure in moving painting beyond the High Baroque, incorporating a greater degree of realism and intimacy, particularly in his genre scenes. His focus on the lives of ordinary people was groundbreaking and paved the way for later developments in genre painting across Europe.

His influence was particularly felt in Venice. His innovative use of light, his color sensibility (itself influenced by Venetian art), and his choice of everyday subjects resonated strongly with Venetian artists of the following generation. The development of the 18th-century Venetian school owes a debt to Crespi's pioneering work.

Several artists were directly influenced by Crespi. Perhaps the most significant was the Venetian painter Giovanni Battista Piazzetta. Piazzetta clearly absorbed Crespi's lessons in chiaroscuro and his sympathetic portrayal of common folk, adapting these elements into his own elegant and distinctive style. Crespi's students also carried his influence forward; Luigi Pergola is mentioned as one who continued his master's style, likely within the Venetian context. Francesco Gaetani is another artist noted as being influenced by Crespi. The name "Mascagni" also appears in sources listing those influenced, though this might refer to a lesser-known figure or require further clarification.

In summary, Crespi's legacy rests on his unique synthesis of Baroque drama and intimate realism, his mastery of light and shadow, and his profound impact on the development of genre painting. He stands alongside his teachers Angelo Michele Toni, Domenico Canuti, and Carlo Cignani, his collaborator Giovanni Antonio Burrini, the masters he admired like Titian, Paolo Veronese, Caravaggio, Guido Reni, Pietro da Cortona, and Rembrandt, and those he influenced, such as Giovanni Battista Piazzetta, Luigi Pergola, and Francesco Gaetani, as a key contributor to the rich tapestry of Italian art.

Conclusion: An Enduring Vision

Giuseppe Maria Crespi "Lo Spagnuolo" was more than just a skilled painter of the late Baroque. He was an innovator whose work signaled a shift in artistic sensibilities. His commitment to observing the world around him, his ability to infuse both religious and secular scenes with deep emotion and psychological insight, and his technical brilliance in manipulating light and color secured his reputation. By elevating everyday life to the level of serious art, Crespi broadened the scope of painting and left an indelible mark on the artists who followed, ensuring his enduring importance in the history of European art. His paintings continue to engage viewers with their blend of dramatic intensity and quiet humanity.