Glyn Warren Philpot (1884-1937) stands as a fascinating and complex figure in the landscape of early twentieth-century British art. Initially celebrated as one of the most gifted portraitists of his generation, his artistic journey led him through Symbolism to a distinctive form of Modernism that challenged the conventions of his time. His work explored profound themes of identity, faith, mythology, race, and sexuality with a technical brilliance that remained constant even as his style evolved. Once a pillar of the establishment, Philpot's later, more radical work led to controversy and a decline in favour, only for his reputation to be significantly re-evaluated in recent decades, securing his place as a pivotal, if sometimes overlooked, British artist.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born in Clapham, London, in 1884, Glyn Philpot moved with his family to Herne in Kent during his childhood. Showing artistic promise early on, he enrolled at the Lambeth School of Art (now the City and Guilds of London Art School) in 1900. Here, under tutors like Philip Connard, he received a solid grounding in traditional techniques. However, it was his move to Paris in 1905, studying at the Académie Julian under Jean-Paul Laurens, that proved truly formative.

Paris exposed Philpot to a whirlwind of artistic influences. While he diligently studied the Old Masters in the Louvre, particularly admiring the Spanish painter Diego Velázquez and the Venetian master Titian, he also absorbed the currents of contemporary French art. The lingering influence of Impressionism and the bolder experiments of Post-Impressionism were unavoidable. He developed a deep appreciation for the work of Auguste Rodin, whose expressive sculptures likely informed Philpot's own later ventures into three dimensions.

Returning to Britain, Philpot’s early work showed an affinity with the rich surfaces and symbolic undertones favoured by artists associated with the later stages of the Aesthetic Movement, such as Charles Ricketts and Charles Shannon, whom he greatly admired. This blend of academic skill, Old Master reverence, and an awareness of modern European trends would characterise the initial phase of his successful career.

The Edwardian Portraitist

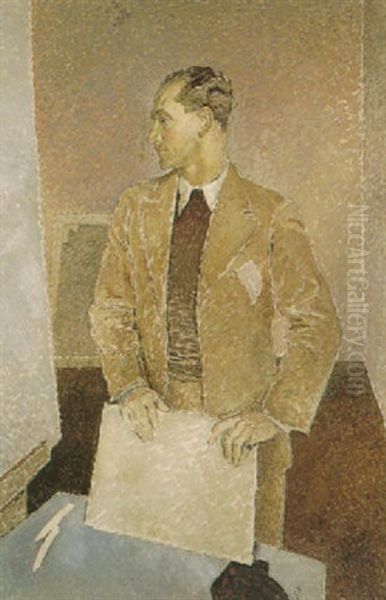

Upon establishing his studio in London, Philpot quickly gained recognition as a portrait painter of exceptional talent. His work during the Edwardian and Georgian periods was highly sought after by society figures, intellectuals, and aristocrats. His portraits were noted for their elegance, sensitivity, and often a psychological depth that distinguished them from the sometimes more superficial bravura of contemporaries like John Singer Sargent or Philip de László.

Philpot possessed a remarkable ability to capture not just a likeness, but also the sitter's presence and inner life. Notable commissions included portraits of Siegfried Sassoon (the war poet, who became a friend), members of the Mond family (including Lady Melchett), political figures like Stanley Baldwin and Oswald Mosley (before the latter's full descent into fascism), and even international royalty such as King Fuad I of Egypt. His skill was undeniable, combining fluent paint handling with sophisticated compositions.

During the First World War, Philpot, unfit for active service due to his health, contributed to the war effort by painting portraits of naval heroes, including several admirals. This work further cemented his public profile. His success culminated in his election as an Associate of the Royal Academy (ARA) in 1915 and a full Royal Academician (RA) in 1923, at the remarkably young age of 39. This marked his acceptance into the highest echelons of the British art establishment.

Embracing Symbolism and Myth

Despite his resounding success as a portraitist, Philpot harboured ambitions beyond capturing the likenesses of the elite. Throughout the 1910s and 1920s, he increasingly turned towards imaginative subjects drawn from mythology, religion, and literature, aligning himself with the enduring currents of Symbolism. This allowed him to explore more personal themes and indulge his taste for allegory and decorative richness.

His Symbolist works often featured dramatic compositions, opulent colour, and a sense of mystery or spiritual intensity. Paintings like The Repentance of Thaïs or the ethereal Angel of the Annunciation showcase this aspect of his oeuvre. He drew inspiration from classical myths, biblical narratives, and medieval legends, reinterpreting them with a modern sensibility. These works connected him to a European tradition of Symbolist painting, echoing artists like Gustave Moreau or Odilon Redon in their imaginative scope, though Philpot's style remained distinctly his own.

This period also saw him explore themes related to performance and the stage, most famously in works depicting the Ballets Russes star Vaslav Nijinsky, such as Nijinsky Before the Curtain. These paintings captured the glamour and intensity of the dance world, blending portraiture with a sense of theatricality that resonated with his Symbolist leanings. His versatility was evident, moving comfortably between society portraits and deeply personal imaginative compositions.

Journeys and the Modernist Shift

The late 1920s and early 1930s marked a significant turning point in Philpot's art and life. Extensive travels through Italy, France (particularly Paris and the South), Germany (Berlin), and North Africa exposed him directly to the latest developments in European Modernism. He encountered the radical innovations of artists like Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse, as well as the starker realities depicted by German Expressionists. These experiences profoundly impacted his artistic vision.

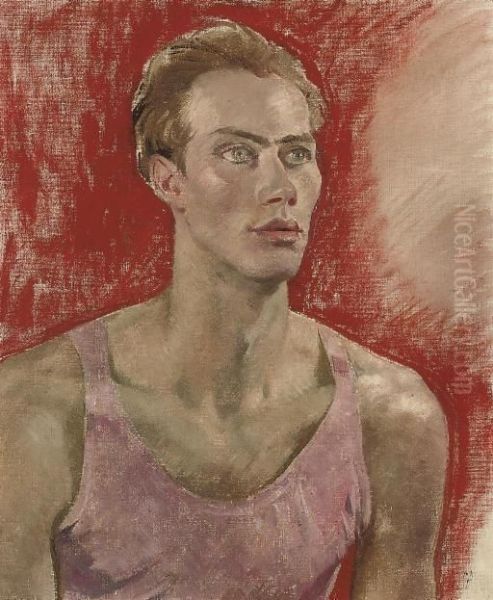

Returning to his London studio, Philpot began to dramatically simplify his style. His brushwork became broader, his forms more stylised and flattened, and his palette shifted towards bolder, sometimes non-naturalistic colours. He abandoned the high academic finish that had characterised much of his earlier work, embracing a more direct and expressive approach. This stylistic evolution was a conscious move away from the Edwardian elegance that had brought him fame.

This shift was not universally welcomed. Some patrons and critics, accustomed to his earlier, more conventional style, were alienated by these modernist experiments. However, for Philpot, it represented a necessary artistic development, a way to engage more directly with contemporary life and his own evolving concerns. His work from this period demonstrates a willingness to take risks and push the boundaries of his own established practice.

Controversy and the Avant-Garde

Philpot's modernist phase produced some of his most powerful and challenging works, but also led to significant controversy. His paintings and sculptures from the early 1930s often combined his new, simplified style with complex, sometimes ambiguous, subject matter drawn from mythology or contemporary life, frequently infused with a palpable homoerotic sensibility.

Works like The Great Pan (1933), depicting a reclining, stylised male nude, and related sculptures, exemplified this new direction. These pieces were stark, formally bold, and thematically provocative. In 1933, this culminated in a notorious incident at the Royal Academy. One or more of his submitted works (accounts vary, but often centre around The Great Pan or similar pieces) were initially accepted but then effectively rejected or strongly discouraged from exhibition by the RA council, who deemed them inappropriate or too radical.

This rejection by the institution that had once eagerly embraced him was a major blow to Philpot, both personally and professionally. It signalled a rupture with the art establishment and contributed to a sense of marginalisation in his later years. While his modernism differed from the abstraction pursued by artists like Ben Nicholson or the surrealism of others, his figurative modernism was nonetheless deemed too challenging for the RA's conservative tastes. He stood somewhat apart from identifiable groups like the Bloomsbury painters (such as Duncan Grant or Vanessa Bell), forging his own path.

Representing Black Masculinity

A particularly significant and pioneering aspect of Philpot's work, spanning both his earlier and later periods, was his engagement with Black subjects, most notably Henry Thomas. Thomas, who was from Jamaica, entered Philpot's employ as a servant around 1929 and soon became a favourite model and close companion, remaining with him until the artist's death. Philpot painted and drew Thomas numerous times, creating sensitive, dignified, and often strikingly intimate portrayals.

Works such as Head of a Negro (Henry Thomas), Man with a Gun (Henry Thomas), and various studies move beyond mere likeness to explore Thomas's individuality and presence. In an era when depictions of Black people in European art were often stereotypical or exoticised, Philpot's portrayals stand out for their humanity and psychological depth. While discussions continue about the power dynamics inherent in the artist-model relationship and potential elements of fascination with the 'other', these works are widely recognised as unusually nuanced and respectful for their time.

Philpot had depicted Black subjects even earlier in his career, sometimes in allegorical or historical contexts. His consistent interest in representing Black figures, particularly Black men, with seriousness and sensitivity marks him as an important, if complex, figure in the history of Black representation in British art, anticipating later explorations by Black artists themselves.

Queer Sensibilities and Coded Narratives

Glyn Philpot was homosexual in an era when male homosexuality was illegal and heavily stigmatised in Britain (under the Criminal Law Amendment Act 1885). While he maintained a degree of public discretion, his sexuality was something of an open secret within artistic and social circles, and it profoundly informed his art, particularly from the 1920s onwards. His work often celebrates male beauty and explores themes of desire, intimacy, and vulnerability.

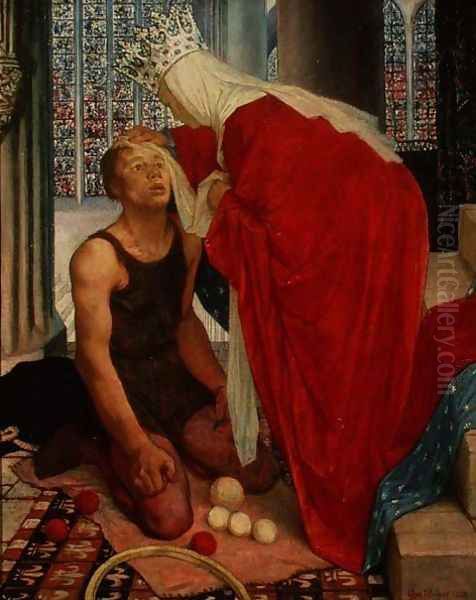

His modernist works of the 1930s became increasingly bold in their exploration of queer themes. The aforementioned Oedipus (1931-32), featuring his young German friend Karl Heinz Müller, or The Juggler, carry strong homoerotic undertones. He often used mythological or biblical subjects, such as St Sebastian or figures from classical antiquity, as vehicles for exploring same-sex desire – a common strategy used by queer artists of the period to encode forbidden themes within acceptable frameworks.

His relationship with Henry Thomas, while primarily documented as employer-employee and artist-model, is often interpreted as having involved a deeper intimacy, reflected in the sensuousness of many of the portraits. Similarly, his long-term, complex relationship with the painter Vivian Forbes was central to his personal life. Philpot's art provides a crucial window into queer experience in early 20th-century Britain, navigating the line between personal expression and social constraint. His work resonates with that of other queer artists of the era, such as the American painter Romaine Brooks, who explored lesbian identity in Paris.

Artistic Relationships: Collaboration and Complexity

Philpot's closest artistic relationship was undoubtedly with Vivian Forbes (1891-1937). Forbes was also a painter, and the two men were partners for many years, sharing studios and aspects of their lives. They travelled together and supported each other's work, though Philpot was always the more successful and critically acclaimed artist. Their styles sometimes showed mutual influence, particularly in decorative elements or shared palettes during certain periods.

However, their relationship was also reportedly complex and at times strained, possibly due to Forbes's own insecurities, reported mental health struggles, and perhaps the pressures of living as a gay couple in an intolerant society. The exact dynamics remain somewhat speculative, but the bond was clearly deep. Forbes was devastated by Philpot's sudden death and tragically took his own life shortly afterwards.

Beyond Forbes, Philpot moved within London's artistic and literary circles. His friendship with Siegfried Sassoon is well-documented through correspondence and the portraits he painted. He would have known many of the leading figures of the day, from established RAs like William Orpen and Augustus John to younger artists forging different paths. While not part of a specific 'school', he was an active participant in the London art world, exhibiting widely and engaging with his contemporaries.

Sculpture and Other Media

While primarily known as a painter, Glyn Philpot was also a talented sculptor. He began working seriously in three dimensions around 1930, often exploring themes and forms that paralleled his paintings of the period. His sculptures, typically in bronze or plaster, shared the simplified, stylised aesthetic of his later paintings, focusing on the human figure, often male nudes derived from mythological or symbolic concepts.

His sculpture The Great God Pan is perhaps his best-known three-dimensional work, directly related to the controversial paintings of the same subject. He also created portrait busts and other figurative pieces. Although his sculptural output was less extensive than his paintings, it demonstrates his versatility and his commitment to exploring form across different media during his modernist phase.

Furthermore, Philpot was an exceptional draughtsman. His drawings, whether preparatory studies for paintings, standalone portraits, or sketches from life, reveal his technical mastery and sensitivity of line. Many drawings, particularly those of Henry Thomas and other male figures, possess an immediacy and intimacy that complements his more formal painted works.

Final Years and Obscurity

Despite his earlier fame and continued artistic output, Philpot's later years were marked by challenges. The RA controversy damaged his standing with the establishment, and the shift in his style meant fewer lucrative portrait commissions. While he continued to exhibit, including internationally (e.g., at the Venice Biennale), he faced increasing financial difficulties. His health, never robust, also remained a concern.

His death came suddenly from a stroke in December 1937, at the age of just 53. The subsequent suicide of Vivian Forbes added a layer of tragedy to his passing. In the decades that followed, particularly after World War II, Philpot's reputation faded. The art world's focus shifted towards abstraction and different forms of modernism, and his blend of traditional skill with figurative modernism fell out of fashion. For a time, he was remembered primarily as an accomplished, if somewhat dated, portraitist.

Rediscovery and Enduring Significance

Beginning in the late 1970s and gaining momentum in subsequent decades, Glyn Philpot's work began to be seriously re-evaluated. Art historians and curators started to look beyond the society portraits to appreciate the full scope and daring of his artistic journey. His engagement with modernism, his exploration of complex themes, and his pioneering representations of Black and queer identities came into sharper focus.

Major exhibitions, including retrospectives at the National Portrait Gallery in London and Pallant House Gallery in Chichester, brought his work to new audiences and solidified his importance. His paintings and sculptures are now held in major public collections, including the Tate, the Ashmolean Museum, the Fitzwilliam Museum, and numerous institutions internationally.

Today, Glyn Philpot is recognised not just for his technical brilliance but for his courage in tackling challenging subjects and evolving his style in response to both personal conviction and the changing artistic landscape. He is seen as a key figure in British modernism, one whose work uniquely bridges tradition and innovation. His explorations of race, sexuality, and identity continue to resonate, making him a vital artist for understanding the complexities of art and society in the early twentieth century and beyond. His legacy is that of a sensitive, searching, and ultimately radical artist who carved a unique path through a transformative era in British art.