William Etty stands as a unique and often controversial figure in the annals of British art. Active during the late Georgian and early Victorian periods, he carved a distinct niche for himself primarily through his dedication to history painting, a genre he populated with sumptuously rendered, often nude, figures. He was, arguably, Britain's first significant painter to specialize in the nude, bringing a richness of colour and a tactile sense of flesh reminiscent of the Continental Old Masters to the London art scene. His career was marked by a tension between critical acclaim and public censure, yet his technical brilliance and unwavering commitment to his artistic vision secured him a lasting, if debated, place in art history.

From York to London: An Unconventional Path

William Etty was born on March 10, 1787, in Feasegate, York. His background was modest; his father was a miller and baker, and the family's financial situation meant Etty received only a limited formal education. Opportunity in York was scarce for a young man with artistic inclinations but no connections or wealth. At the young age of twelve, around 1799, he was apprenticed to a printer in Hull, Robert Peck of the Hull Packet newspaper.

For seven long years, Etty endured the drudgery of the printing trade, a profession far removed from his artistic aspirations. He later described this period as one of servitude, though it likely instilled in him a discipline and work ethic that would serve him well. Throughout his apprenticeship, he continued to sketch and practice drawing whenever possible, nurturing the artistic spark that refused to be extinguished. Upon completing his indenture in 1806, Etty, now a young man, made the pivotal decision to move to London, the heart of the British art world, to pursue his true calling.

Academic Foundations and Early Struggles

Arriving in London, Etty sought formal training. His talent, perhaps raw but evident, caught the attention of the established painter John Opie. Opie, recognizing Etty's potential, provided crucial encouragement and, significantly, recommended him to Henry Fuseli, the Keeper of the Royal Academy Schools. This connection facilitated Etty's admission to the prestigious Royal Academy Schools in 1807. Here, he immersed himself in the rigorous academic curriculum, which emphasized drawing from antique casts and, crucially for his later development, from live models in the life class.

During this formative period, Etty also benefited from the tutelage of Sir Thomas Lawrence, one of the leading portrait painters of the day. Etty spent about a year formally studying with Lawrence, absorbing aspects of his sophisticated technique and elegant style, although their artistic temperaments ultimately diverged. Alongside formal instruction, Etty dedicated himself to the traditional practice of copying works by Old Masters, honing his skills by studying the techniques of renowned painters whose works were accessible in London collections or through prints.

Despite his dedication and training at the highest level, Etty's early years in London were marked by a distinct lack of commercial success or critical recognition. His submissions to the Royal Academy's annual exhibitions were often overlooked or poorly hung. He struggled financially and faced repeated disappointments, a period that tested his resolve but ultimately strengthened his determination to master his craft according to his own artistic principles.

Forging a Reputation: The Rise to Prominence

The turning point in William Etty's career arrived in 1821 with the exhibition of his ambitious history painting, Cleopatra's Arrival in Cilicia (also known as The Triumph of Cleopatra). Displayed prominently at the Royal Academy, the painting caused a sensation. It was a large, complex composition depicting the Egyptian queen's famously seductive arrival to meet Mark Antony, featuring a lavish barge and numerous attendants, including several prominent nude figures. While the subject matter's sensuality raised some eyebrows, the painting was widely praised for its rich colouring, dynamic composition, and, particularly, Etty's masterful rendering of flesh tones. It established his reputation almost overnight.

Building on this success, Etty's profile within the art establishment grew rapidly. His technical skill, especially his handling of the human form, could no longer be ignored. In 1824, he was elected an Associate of the Royal Academy (ARA). Just four years later, in 1828, he achieved the highest professional honour available to a British artist: election as a full Royal Academician (RA). This prestigious membership cemented his status among the elite of the London art world, alongside figures like J.M.W. Turner and Sir David Wilkie.

Another work that significantly boosted his early reputation was The Combat: Woman Pleading for the Vanquished, exhibited in 1825. This dramatic scene, showcasing Etty's ability to depict intense emotion and physical struggle through powerful male nudes, was purchased by fellow artist John Martin. These successes marked Etty's arrival as a major force in British painting, albeit one whose chosen subject matter would continue to provoke debate.

The Etty Style: Colour, Form, and Influence

William Etty developed a highly distinctive artistic style characterized by its rich, jewel-like colours, fluid brushwork, and profound understanding of human anatomy. His primary inspiration came not from contemporary British trends, but from the Venetian masters of the Renaissance and the Flemish Baroque painters. He made several trips to Italy, notably in 1822-1824, where he immersed himself in the art of Titian, Veronese, and Tintoretto. He deeply admired their handling of colour, light, and sensual subject matter.

The influence of Peter Paul Rubens is also profoundly evident in Etty's work, particularly in the dynamic compositions, the robust physicality of his figures, and the warm, vibrant palette he employed. Etty sought to emulate the 'glow' and richness he perceived in their canvases, particularly in the rendering of skin, which he believed was paramount. He famously declared, "Flesh is the thing... Give me flesh." This dedication resulted in depictions of the human body that possessed an unparalleled sense of vitality and realism within British art of the period.

While grounded in the study of Old Masters, Etty's style was not merely imitative. He combined the richness of Venetian colour and the energy of Rubens with the academic discipline learned at the Royal Academy and under Sir Thomas Lawrence. His work often blends classical ideals of form with a romantic sensibility, evident in the emotional intensity and dramatic narratives of his history paintings. This unique synthesis set him apart from many of his British contemporaries.

Grand Themes: History, Mythology, and the Bible

Etty primarily saw himself as a history painter, tackling grand themes drawn from classical mythology, the Bible, and historical accounts. This genre was considered the highest form of art according to academic tradition, demanding skill in composition, narrative, and the depiction of the human figure in complex poses and emotional states. Etty embraced these challenges, producing a significant body of large-scale works intended for public exhibition.

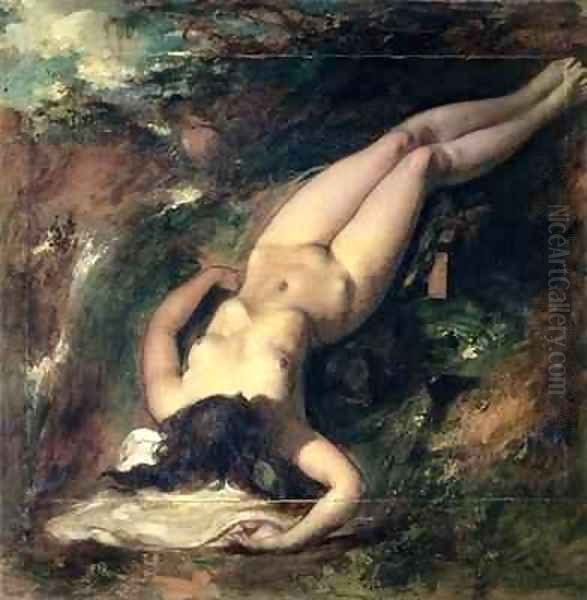

His mythological subjects often allowed him to explore the nude figure within established narratives. The Birth of Venus (1843), Venus and Adonis (1836), and The Judgment of Paris are prime examples, showcasing his ability to render idealized yet sensuous bodies within classical settings. He was drawn to stories involving beauty, temptation, and divine power, often infusing them with a palpable sense of drama.

Biblical stories also provided fertile ground. His Judith series, comprising three paintings depicting the heroic Israelite widow preparing to decapitate the Assyrian general Holofernes, demonstrates his capacity for conveying narrative tension and psychological depth. David's Chief Captain further illustrates his engagement with Old Testament subjects. These works, alongside historical pieces like The Duke of Buckingham's Ascent to Heaven (1825-1835), reveal his ambition to rival the great history painters of the past.

Beyond these grand narratives, Etty also produced powerful depictions of physical struggle and prowess, such as The Wrestlers (1840), a dynamic study of intertwined male bodies showcasing his anatomical knowledge. His painting Youth on the Prow, and Pleasure at the Helm, exhibited in 1832, used allegory to explore themes of life's journey, again featuring prominent nude figures representing abstract concepts. These works cemented his reputation for tackling ambitious subjects with technical virtuosity.

The Controversial Nude: Art versus Morality

The nude figure was absolutely central to William Etty's art, and it was the primary source of the controversy that surrounded him throughout his career. In the increasingly prudish atmosphere of early Victorian Britain, the public display of naked bodies, particularly female nudes rendered with Etty's characteristic realism and sensuousness, was often deemed shocking and morally suspect. Critics frequently accused his works of being indecent, voluptuous, or even pornographic, arguing that they appealed to prurient interests rather than lofty artistic ideals.

While Etty defended his focus on the nude as essential for depicting historical and mythological truth and for celebrating the beauty of the human form – God's creation, as he saw it – his detractors remained unconvinced. The criticism came not only from the press and the public but also from within the art world. The landscape painter John Constable, for instance, famously remarked that Etty's figures often looked like they'd been "rolled in rotten ivory," suggesting a lack of classical refinement and an overly fleshy, realistic quality that disturbed contemporary sensibilities.

Paintings like Candaules, King of Lydia, Shewing his Wife by Stealth to Gyges, One of his Ministers, as She Goes to Bed were particularly provocative, depicting scenes of voyeurism and female vulnerability that transgressed Victorian codes of propriety. Even his mythological nudes, while drawing on classical precedent, were often seen as too lifelike, too lacking in idealization, to be considered purely artistic statements. This constant tension between artistic admiration for his skill and moral condemnation of his subject matter defined Etty's public reception.

Dedication to Life Drawing: The Foundation of His Art

Underpinning Etty's mastery of the human form was his unwavering dedication to drawing from life. He considered the life class – the practice of sketching live, usually nude, models – to be the cornerstone of artistic training and essential for maintaining his skills. He was a fixture at the Royal Academy's life class for almost his entire career, attending sessions alongside students even after becoming a celebrated Royal Academician. This dedication was unusual for an established artist and spoke volumes about his commitment to anatomical accuracy and the realistic depiction of the human body.

His commitment extended beyond the formal setting of the Academy. He frequently employed models in his own studio, producing countless life studies in oil and chalk. These studies were not merely preparatory sketches but often works of art in their own right, showcasing his ability to capture pose, musculature, and the play of light on skin with remarkable speed and accuracy. This constant practice directly informed the figures that populated his large exhibition pieces.

However, even this dedication to academic practice drew criticism. In the context of Victorian society, Etty's intense focus on the nude model, particularly female models, was sometimes viewed with suspicion. His habit of attending life classes alongside much younger students was occasionally seen as eccentric or even inappropriate. For Etty, though, there was no substitute for direct observation; it was the fundamental basis upon which his art, particularly his celebrated rendering of flesh, was built.

Art World Connections and Influences

Throughout his career, William Etty navigated the complex social and professional landscape of the London art world. His relationship with his former teacher, Sir Thomas Lawrence, remained respectful, though their artistic paths diverged significantly. Etty's election to the Royal Academy placed him among the leading artists of his generation, including the landscape genius J.M.W. Turner, the celebrated genre painter Sir David Wilkie, and fellow history painter Benjamin Robert Haydon, whose ambitions often outstripped his success. Etty also shared the Academy spaces with artists like William Mulready, known for his charming genre scenes, and the rising star of animal painting, Sir Edwin Landseer, who had been a fellow student in the RA Schools.

Etty maintained important connections outside the London-centric RA. His friendship with John Harper, a fellow Yorkshireman involved with the York Philosophical Society, was particularly significant. Harper was described as a close confidant and provided support and encouragement. They collaborated on at least one occasion, with Harper potentially assisting with the landscape elements in Etty's painting The Strid (1841). Etty's ties to his native York remained strong, involving him with local figures like James Atkinson and John Brook in efforts related to civic life and heritage.

His travels, especially to Italy, were crucial not just for studying Titian and Veronese but also for potentially interacting with the contemporary European art scene, although specific records of close friendships with continental artists are scarce. His primary artistic dialogue seems to have been with the Old Masters he revered and the British contemporaries he exhibited alongside and occasionally competed against at the Royal Academy exhibitions. His unique style, however, ensured he always stood somewhat apart.

York, Later Life, and Personal Character

Despite achieving fame and success in London, William Etty retained a deep affection for his hometown of York. He visited regularly throughout his life and, in 1848, suffering from declining health (likely asthma and chest complaints), he retired from the bustling London scene and returned permanently to York, purchasing a house in Coney Street. He became an active figure in the city's cultural and civic life during his later years.

Notably, Etty was a passionate advocate for the preservation of York's historic architecture. He played a prominent role in the successful campaign to save the city's medieval walls from demolition, demonstrating a commitment to heritage that complemented his artistic endeavours. He also championed the cause of art education in York, being instrumental in the founding of the York Government School of Design in 1842 (a precursor to the York Art Gallery and York College of Art), serving as a vital link between the London art establishment and provincial artistic development.

In his personal life, Etty remained a bachelor. For many years, his household was managed by his niece, Mary (or Betsy, as she was known) Etty, who provided companionship and domestic stability. Accounts suggest he was a man of relatively simple habits, deeply religious (a devout Methodist), and somewhat introverted and socially awkward, perhaps contributing to his relatively small circle of intimate friends despite his professional prominence. An earlier disappointment in love, reportedly involving a failed engagement to a daughter of Lord Hatherton, may have contributed to his decision to remain unmarried.

Final Years, Death, and Initial Legacy

William Etty's final years in York were relatively quiet, marked by increasing ill health which curtailed his painting activity. He had achieved considerable financial success through his art, enabling a comfortable retirement. His reputation, while still subject to the familiar criticisms regarding his nudes, was largely secure within the art establishment. He died in York on November 13, 1849, at the age of 62.

He was buried in the churchyard of St Olave's Church in Marygate, York, close to the city walls he had helped to save. His tombstone inscription, reflecting his character and priorities, reportedly highlighted his dedication to his studies, his care for his students, and his devotion to his art. In the immediate aftermath of his death, his reputation perhaps suffered a slight decline. The rise of new artistic movements, particularly the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood with members like Dante Gabriel Rossetti and John Everett Millais, brought different aesthetic values to the fore, emphasizing detailed realism and literary or medieval themes over Etty's more painterly, classically inspired nudes.

Furthermore, the persistent moral objections to his subject matter continued to colour perceptions of his work in the high Victorian period. While his technical skill was rarely disputed, the perceived sensuality of his paintings made them problematic for an era increasingly concerned with public morality and decorum. His work, though present in major collections, fell somewhat out of critical fashion for a time.

Shifting Reputations: Re-evaluation in Modern Times

The 20th and 21st centuries witnessed a significant re-evaluation of William Etty's work and his place in British art history. As Victorian moral codes relaxed and art historical scholarship adopted broader perspectives, Etty's paintings began to be appreciated anew for their artistic merits, largely independent of the controversies they once ignited. His technical brilliance, particularly his mastery of colour and the rendering of the human form, received renewed attention.

Major exhibitions played a crucial role in this reassessment. The Tate Britain's landmark show "Exposed: The Victorian Nude" in 2001-2002 prominently featured Etty's work, contextualizing it within the broader development of the nude in British art and highlighting his pioneering role. In 2010, the Manchester Art Gallery showcased his monumental painting Ulysses and the Sirens following its restoration, bringing one of his major works back into the public eye. The British Museum also conserved and studied works like his Prometheus.

Perhaps most significantly, the York Art Gallery mounted a major retrospective titled "William Etty: Art and Controversy" in 2011-2012. This exhibition brought together over 100 of his works, offering the most comprehensive overview of his career in decades and prompting fresh critical analysis. Another York exhibition followed in 2013. These initiatives allowed audiences and scholars to appreciate the full range of his output, from intimate life studies to grand historical compositions, and to understand the complexities of his reception. Critics like John Ruskin, though complex in his views, had paid attention to Etty in his time, and later scholars began to unpack his influence and significance more fully.

Enduring Legacy: A Pioneer Reclaimed

Today, William Etty is recognized as a major figure in 19th-century British art. His primary legacy lies in his status as the first significant British painter to make the nude a central focus of his oeuvre. He challenged the prevailing tastes and moral codes of his time, insisting on the artistic importance of the human form, rendered with a richness and vitality inspired by the Continental masters he admired. His skill in depicting flesh tones remains remarkable, setting a standard that few British artists have matched.

His influence extended beyond his specific subject matter. His bold use of colour and fluid brushwork offered an alternative to the tighter, more linear styles often favoured in British academic painting. While direct followers who explicitly copied his style were perhaps few, his work demonstrated the expressive possibilities of oil paint and undoubtedly informed later generations of artists grappling with the representation of the human body. His commitment to art education, particularly through his role in establishing the York School of Design, also forms part of his contribution.

His works are held in major public collections, including the Tate galleries, York Art Gallery, the Victoria and Albert Museum (formerly the South Kensington Museum), the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and Manchester Art Gallery, ensuring their continued accessibility. While the debate about the line between sensuousness and sensationalism in his art may continue, William Etty's position as a technically brilliant, historically important, and uniquely dedicated painter of the human form is now firmly established.

Conclusion: A Singular Vision

William Etty's career presents a fascinating study in artistic conviction versus societal norms. He pursued his singular vision with unwavering dedication, mastering the depiction of the human form and infusing his canvases with a richness of colour and sensuality largely derived from his beloved Venetian and Flemish masters. This dedication brought him professional success and election to the highest ranks of the Royal Academy, yet simultaneously exposed him to persistent criticism for offending the moral sensibilities of Victorian Britain. He remains a testament to the power of technical skill and the enduring, if sometimes uncomfortable, allure of the human figure in art. His reclamation by later generations confirms his importance as a distinctive and influential voice in the story of British painting.