Charles Sims stands as a fascinating, complex, and ultimately tragic figure in the landscape of British art during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Spanning the transition from Victorian sensibilities through the Edwardian era and into the turbulent aftermath of the First World War, Sims's artistic journey reflects both the prevailing currents of his time and a deeply personal, often tormented, inner world. Initially celebrated for his light-filled, idyllic scenes of family life and mythological fancy, his later work took a radical turn towards symbolic abstraction, driven by personal loss and psychological strain. His career, marked by both significant recognition within the establishment and controversial clashes, culminated in a series of startlingly modern works and a premature, self-inflicted death, leaving behind a legacy that continues to invite interpretation and reassessment.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

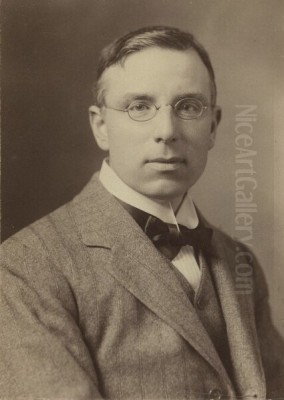

Charles Henry Sims was born in Islington, London, on January 28, 1873. His formative years were spent not in the bustling capital, but in the seaside town of Margate, Kent. An unfortunate leg injury sustained in childhood resulted in a permanent limp. This physical limitation proved inadvertently pivotal for his future path; it precluded him from pursuing a planned career in business, redirecting his energies towards the arts. This shift marked the beginning of a lifelong engagement with visual expression, a path that would lead him through various esteemed institutions and artistic circles.

His formal art education began in London, initially at the South Kensington School of Art, a key institution for design and applied arts training. He later progressed to the prestigious Royal Academy Schools, the educational heart of the British art establishment. However, his time at the RA Schools was reportedly cut short; accounts suggest he was expelled due to "unconventional behavior," an early indicator, perhaps, of an independent spirit that would sometimes clash with institutional norms throughout his career. Seeking broader horizons and different pedagogical approaches, Sims, like many aspiring artists of his generation, travelled to Paris.

In the French capital, a global hub for artistic innovation at the time, Sims enrolled at the renowned Académie Julian. This large, independent art school attracted students from across the world and offered a more liberal alternative to the rigid structure of the official École des Beaux-Arts. Here, students could work from the live model with relative freedom, absorbing diverse influences. Sims also spent time studying at the studio of Bas Merlin. This period in Paris exposed him to the lingering influences of Impressionism and the burgeoning Post-Impressionist movements, broadening his technical skills and artistic perspectives beyond the confines of British academic tradition.

Emergence and Early Success

Returning to London, Sims faced the challenges common to young artists establishing their careers. His breakthrough came in 1906 with his first solo exhibition at the influential Leicester Galleries in London. This show proved highly successful, effectively launching his professional career and establishing his reputation with critics and the public. The works displayed likely showcased the style that would characterize his early-to-mid career: charming, often sun-dappled scenes combining landscape, portraiture, and genre elements.

His subject matter frequently revolved around idyllic outdoor settings, capturing the play of light and atmosphere with a vibrant palette and fluid brushwork. These landscapes were often populated by figures, particularly women and children, frequently drawn from his own growing family. Works from this period exude a sense of warmth, domestic harmony, and a gentle, romantic sensibility. There's an affinity with the spirit, if not always the technique, of French Impressionists like Claude Monet or Pierre-Auguste Renoir in their focus on light and everyday leisure, filtered perhaps through the lens of British interpreters like Philip Wilson Steer or George Clausen, who were adapting Impressionist principles to native subjects.

Sims also demonstrated a particular aptitude for working in tempera, an ancient medium involving pigment mixed with a binder like egg yolk. During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, there was a notable revival of interest in tempera painting in Britain, championed by artists associated with the Arts and Crafts movement and figures like Joseph Southall of the Birmingham School. Sims's adoption of this technique showcased his technical versatility and aligned him with artists seeking alternatives to oil paint, often valuing tempera for its luminosity and precise finish. His early works, whether in oil or tempera, often possessed a decorative quality, sometimes hinting at mythological or allegorical themes woven into contemporary scenes, creating a distinctive blend of realism and fantasy.

Royal Academy Recognition and Pre-War Style

Sims's growing reputation led to recognition from the very institution that had reportedly expelled him earlier. He was elected an Associate of the Royal Academy (ARA) in 1908, a significant step confirming his acceptance within the mainstream art world. Full membership as a Royal Academician (RA) followed in 1915. His election placed him among the leading figures of the British art establishment during the Edwardian period and the reign of George V. The RA, under presidents like Sir Edward Poynter, remained a powerful institution, though increasingly challenged by modernist movements exhibiting elsewhere.

During the years leading up to the First World War, Sims consolidated his success, producing works that were popular both at the RA's annual Summer Exhibitions and with private collectors. His style often blended a late-Victorian taste for narrative and sentiment with a more modern handling of light and colour. He became particularly known for paintings depicting his own children at play in sunlit gardens or coastal settings, images that resonated with Edwardian ideals of family and innocence. These works often carried titles hinting at allegory or classical mythology, gently overlaying the everyday with a sense of timeless wonder.

A prime example of this pre-war style is Clio and the Children (1913, exhibited 1915). This painting depicts the Muse of History, Clio, reading from a scroll to a group of children (likely Sims's own) in an idyllic Sussex landscape. It perfectly encapsulates his ability to merge the mythological with the familiar, creating a scene that is both contemporary and imbued with classical resonance. The painting showcases his skill in composition, his sensitivity to light, and his affectionate portrayal of childhood. It represents the peak of his popular, pre-war manner, an art seemingly untouched by the radical experiments of Cubism or Fauvism then emerging on the continent, yet possessing its own distinct charm and painterly quality, standing alongside the work of contemporaries like John Singer Sargent in its technical assurance, albeit with a different sensibility.

The Shadow of War

The outbreak of the First World War in 1914 cast a long and devastating shadow over European society, and its impact on Charles Sims was profound and deeply personal. Like countless families across Britain and the continent, the Sims family experienced the ultimate tragedy of the conflict. His eldest son was killed in action while serving on the Western Front. This shattering loss inflicted a deep psychological wound from which Sims arguably never fully recovered. The war irrevocably altered his worldview and, consequently, the trajectory of his art.

The idyllic visions that had characterized much of his pre-war output seemed increasingly untenable in the face of such widespread suffering and personal grief. While he continued to work, a shift began to occur, subtly at first, then more dramatically. The trauma of his son's death manifested directly in his artistic practice. In a poignant act of revision, Sims later returned to his 1913 painting Clio and the Children. He painted over the scroll held by the Muse, changing its colour to a stark, blood red. This alteration transformed the work's meaning, turning the previously innocent scene of historical learning into a somber commentary on the brutal reality of contemporary history and the sacrifice of youth in the war. The red scroll became a symbol of loss, staining the idyllic landscape with the inescapable presence of conflict.

During the war years, Sims also undertook commissions that reflected the somber mood of the nation. He created a series of allegorical paintings titled The Seven Sacraments of the Holy Church. While the exact nature and context of this series require further research, the choice of a profound religious theme suggests an artist grappling with fundamental questions of faith, suffering, and redemption in a time of crisis. Unlike official war artists such as Paul Nash or C.R.W. Nevinson, whose work often directly depicted the trenches and devastation of the front lines, Sims's response was more allegorical and internalized, exploring the spiritual and psychological impact of the conflict rather than its physical manifestation. The war marked a definitive turning point, shattering the Edwardian optimism reflected in his earlier work and setting the stage for the more complex, troubled, and experimental art of his later years.

Keeper of the Royal Academy and Mounting Tensions

In the aftermath of the war, despite the personal trauma he carried, Sims's standing within the art establishment continued to rise, culminating in a significant appointment. In 1920, he was appointed Keeper of the Royal Academy. This prestigious position effectively made him the head of the RA Schools, responsible for overseeing the training of the next generation of artists. It was a role of considerable influence and responsibility within the heart of the British art world. His appointment might have been seen as bringing a slightly more modern, though still broadly traditional, perspective to the Academy's pedagogy.

However, Sims's tenure as Keeper (1920-1926) was fraught with difficulty. The role placed him in a potentially awkward position: an artist whose own work was beginning to move in more personal and unconventional directions, now charged with upholding the traditions of an institution often perceived as resistant to change. Reports from the period suggest increasing friction between Sims and the RA Council, particularly with the RA President, Sir Frank Dicksee, a painter known for his adherence to academic tradition. Sims's own artistic explorations and perhaps his personality, marked by the lingering effects of war trauma, seem to have contributed to a growing sense of isolation and conflict within the Academy.

This tension was exemplified by controversies surrounding his public commissions. Sims was one of several prominent artists commissioned to paint large murals for St Stephen's Hall in the Palace of Westminster, depicting scenes from British history under the umbrella theme 'The Building of Britain'. Sims's contribution was King John confronted by his Barons assembled in arms demands his assent to Magna Carta. When unveiled, the mural drew criticism for its perceived stylistic incompatibility with the other works in the series, which included contributions by artists like George Clausen, William Rothenstein, and Vivian Forbes. Critics pointed to differences in colour palette, scale, and overall approach, suggesting Sims's work disrupted the intended harmony of the decorative scheme. While the mural had its defenders, the controversy highlighted Sims's increasingly individualistic path and the challenges he faced in conforming to institutional expectations. The pressures of the Keepership, combined with his internal struggles, appear to have taken a significant toll on his mental health during these years.

The "Spiritual Ideas": A Radical Departure

The final phase of Charles Sims's artistic output represents a dramatic and startling departure from his earlier work and, indeed, from the mainstream of British art at the time. In the years leading up to his resignation as Keeper and his subsequent death, Sims produced a series of paintings he termed his "Spiritual Ideas." Six of these works were submitted to the Royal Academy's Summer Exhibition in 1928, shortly before his death, and exhibited posthumously. Collectively titled The Agony and the Ecstasy, they caused a sensation and remain his most debated and perhaps most significant contribution.

These paintings are unlike anything else in his oeuvre. They abandon representational clarity for a highly symbolic, abstract, and intensely emotional visual language. Figures dissolve into swirling vortexes of colour and energy; cosmic forces seem to clash and merge; themes of suffering, spiritual struggle, ecstasy, rebellion, and transcendence are explored with raw, visceral power. Titles of individual works within the series, such as Man's Last Pretence of Consummation in Indifference, Here am I, My Pain Beneath Your Sheltering Hand, I am the Abyss and I am Light, convey the profound psychological and spiritual territory Sims was charting.

The style is characterized by vibrant, almost Fauvist colours, dynamic, often turbulent compositions, and a move towards non-objective forms. Critics and art historians have drawn comparisons to the abstract experiments of Wassily Kandinsky, the dynamism of Italian Futurism, or even the visionary intensity of William Blake. Exhibited within the traditional halls of the Royal Academy, these works were shockingly modern and deeply personal, offering a stark contrast to the more conventional paintings surrounding them. They were interpreted by some as evidence of his genius reaching a new, visionary height, while others saw them as disturbing reflections of a mind under immense strain. Undoubtedly, these late works are inextricably linked to Sims's deteriorating mental state and his grappling with the trauma and existential questions that haunted him. They represent a desperate, powerful attempt to give form to complex inner experiences, pushing the boundaries of his own art and challenging the expectations of his audience.

Final Years and Tragic End

The cumulative pressures of his role at the Royal Academy, the unresolved trauma of his son's death, and his intense, perhaps overwhelming, artistic explorations took a severe toll on Charles Sims's mental health. In 1926, suffering from what was likely diagnosed at the time as neurasthenia or a nervous breakdown, he resigned from his position as Keeper of the Royal Academy. This marked the end of his formal association with the institution that had been central to his career, albeit often contentiously. He sought respite away from the pressures of London, hoping perhaps to find peace and recovery.

However, the inner turmoil persisted. His final artistic statements, the "Spiritual Ideas" paintings, were created during this period of intense psychological distress. He submitted these challenging works to the RA Summer Exhibition in the spring of 1928. Shortly thereafter, on April 13, 1928, while staying in St. Boswells, Roxburghshire, Scotland, Charles Sims took his own life by drowning. He was 55 years old.

His suicide sent shockwaves through the British art world. When his final paintings were displayed posthumously at the Royal Academy just weeks later, they were viewed through the lens of this tragedy. The already potent emotional charge of the works was amplified, seen by many as a direct expression of the mental anguish that led to his death. His end was a tragic culmination of a life marked by early promise, significant achievement, profound personal loss, internal conflict, and a final, radical burst of artistic creativity that pushed him beyond the limits of convention and, perhaps, endurance.

Legacy and Reassessment

In the immediate aftermath of his death, Charles Sims's reputation was complex and somewhat polarized. His earlier, more accessible works – the sunlit landscapes, the charming family scenes, the mythological fantasies – remained popular and continued to be appreciated for their technical skill and appealing subject matter. These paintings secured his place in many public collections, including the Tate Gallery in London, as well as galleries in Edinburgh, Liverpool, and internationally in places like Sydney. His works had also been acquired by the Luxembourg Museum in Paris during his lifetime, indicating international recognition.

However, his final, challenging "Spiritual Ideas" series cast a long shadow. While acknowledged as powerful and unique, they were often interpreted primarily through the tragic circumstances of his suicide, sometimes dismissed as the products of a disturbed mind rather than being fully assessed on their artistic merits within the context of emerging modernism. For much of the mid-20th century, as artistic tastes shifted towards different forms of abstraction and post-war movements, Sims's overall contribution was somewhat overlooked, particularly his later, more experimental phase.

In more recent decades, there has been a gradual reassessment of Charles Sims's work and legacy. Art historians have begun to look beyond the biographical tragedy to appreciate the artistic significance of his entire career, particularly the boldness and originality of his late paintings. He is increasingly recognized as a significant figure in the transition from late Victorian/Edwardian art towards early British modernism. His exploration of psychological depth, his willingness to experiment with form and colour, and his engagement with symbolism and spiritual themes place him in a unique position. While perhaps not a central figure in the avant-garde movements led by artists like Wyndham Lewis or members of the Bloomsbury Group, Sims forged his own distinct path. His work reflects the tensions of an era grappling with tradition, modernity, and the profound impact of war, filtered through a deeply personal and ultimately fragile sensibility. His complex journey and the haunting power of his art, especially his final works, continue to fascinate and resonate, securing his place as an important, if often unsettling, voice in British art history.