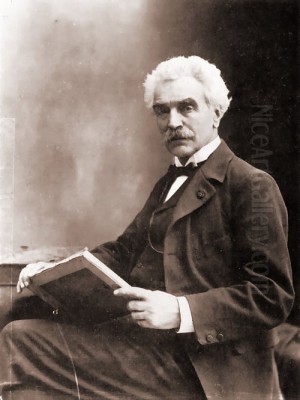

Jean-Léon Gérôme stands as one of the most significant and complex figures in 19th-century French art. Born on May 11, 1824, in Vesoul, Haute-Saône, and passing away in Paris on January 10, 1904, Gérôme was a master painter and sculptor whose career spanned a period of dramatic artistic change. He became a leading exponent of the Academic tradition, renowned for his meticulously detailed and highly finished works that drew upon history, mythology, and his extensive travels to the East. While enormously successful and influential during his lifetime, his staunch opposition to emerging modern art movements like Impressionism, coupled with later critiques of his Orientalist subjects, has shaped his controversial yet undeniably important legacy.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Gérôme's artistic journey began in his hometown of Vesoul before he moved to Paris in 1840. His most formative training occurred under the tutelage of Paul Delaroche, a highly respected history painter. Gérôme became one of Delaroche's most devoted students, absorbing his master's emphasis on historical accuracy, dramatic narrative, and polished technique. He even accompanied Delaroche on a trip to Italy in 1843, a journey that exposed him to the masterpieces of the Renaissance and the ruins of antiquity, further solidifying his classical inclinations.

When Delaroche closed his teaching studio, Gérôme briefly studied with the Swiss artist Charles Gleyre, known for his own mythological and historical scenes. Though his time with Gleyre was shorter, it placed him within another significant academic atelier. Throughout his early development, Gérôme also deeply admired the work of Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, the undisputed leader of French Neoclassicism. Ingres's emphasis on linear precision, smooth surfaces, and idealized forms left a lasting imprint on Gérôme's own style, particularly his draftsmanship.

Gérôme made his public debut at the prestigious Paris Salon of 1847 with the painting The Cockfight (Jeunes Grecs faisant battre des coqs). This work, depicting a classical genre scene with youthful figures and remarkable detail, was an immediate success. It earned him a third-class medal and marked him as a significant new talent within the Academic system, launching a long and prolific career exhibiting at the Salon, the epicenter of the official French art world.

Ascendancy in the Academic World

Following his successful debut, Gérôme rapidly established himself as a major figure in French Academic painting. He continued to produce works that aligned with the tastes of the Salon jury and the public, focusing on historical, mythological, and religious themes rendered with extraordinary technical skill. His painting The Virgin, the Infant Jesus and St. John (1848) and Anacreon, Bacchus and Cupid (1848) earned him a second-class medal at the Salon of 1848, confirming his rising status.

His ambition grew, leading him to tackle large-scale historical compositions. Commissioned by the state under Napoleon III, The Age of Augustus, the Birth of Christ (also known as Siecle d'Auguste, completed 1855) was a vast allegorical history painting intended for the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Amiens, though it eventually entered the collection of the Musée d'Orsay. While showcasing his research and compositional ability, some critics found it lacked emotional depth, prioritizing archaeological detail over profound meaning – a criticism that would occasionally resurface throughout his career.

Gérôme excelled in depicting dramatic moments from classical antiquity and history. Phryne before the Areopagus (1861), showing the legendary Greek courtesan revealing her beauty to her judges, became one of his most famous and somewhat scandalous works, admired for its skillful rendering of the nude figure and dramatic tension. Similarly, The Death of Caesar (1867), a meticulously researched depiction of the assassination, captured the historical moment with cinematic intensity and is now housed in the Walters Art Museum, Baltimore. Another notable history painting, The Death of Marshal Ney (1867), portrayed the execution of one of Napoleon's most famous commanders with stark realism.

The Lure of the East: Gérôme the Orientalist

A pivotal aspect of Gérôme's career was his engagement with Orientalism – the depiction of North African, Middle Eastern, and Ottoman cultures by Western artists. His interest was sparked early, and following the Age of Augustus commission, he undertook his first major journey eastward, visiting Constantinople (Istanbul) in 1853. This was followed by his first trip to Egypt in 1856, a destination he would return to multiple times throughout his life, along with excursions to Syria, Palestine, and Asia Minor.

These travels provided Gérôme with a wealth of firsthand material – sketches, photographs, costumes, and artifacts – that he meticulously incorporated into his paintings back in his Paris studio. His Orientalist works became immensely popular, offering European audiences detailed, seemingly authentic glimpses into exotic lands. These paintings often focused on scenes of daily life, religious practices, marketplaces, and landscapes, rendered with his characteristic precision and vibrant color.

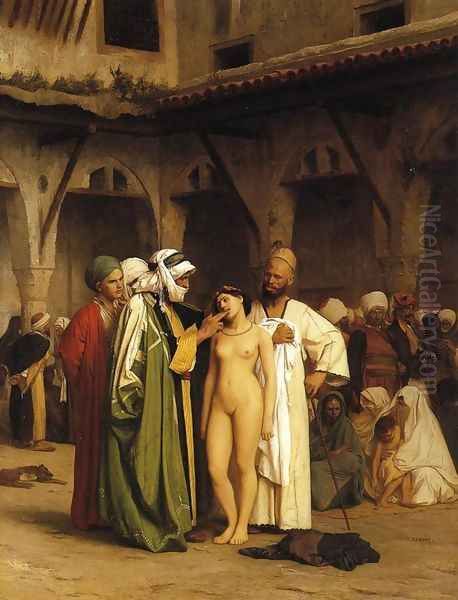

Key works from this period include Prayer in the Mosque (various versions), depicting worshippers with ethnographic detail; The Slave Market (versions from the 1860s), a controversial yet highly finished scene; Arabs Crossing the Desert (1870), capturing the atmosphere of the landscape; and Cafe House, Cairo (also known as The Hookah Smoker), presenting a tranquil moment of leisure. His paintings often featured architectural accuracy, detailed renderings of textiles and objects, and a strong sense of atmosphere, contributing to their perceived realism.

However, his most famous and later most criticized Orientalist work is arguably The Snake Charmer (c. 1879). Depicting a nude young boy charming a snake before an audience of seated men against a backdrop of intricate tilework, the painting exemplifies Gérôme's technical mastery. Yet, it also became a focal point for later critiques of Orientalism, accused of presenting a stereotyped, eroticized, and potentially exploitative view of the East, catering to Western fantasies rather than offering a nuanced portrayal. Other works mentioned in records include Turkish Prisoner and Turkish Butcher (both exhibited at the 1863 Salon), The Expulsion of the Hare (1869), and the intriguingly titled The Visit of the King Fa Hian to Fontenelle (1865), showcasing the breadth of his Eastern-inspired subjects.

Gérôme the Sculptor

While primarily known as a painter, Gérôme turned increasingly to sculpture later in his career, beginning around the late 1870s. This was not an entirely separate endeavor but often intertwined with his painted subjects and his interest in classical antiquity. He brought the same meticulous attention to detail and realism to his three-dimensional work.

One of his most famous sculptural projects relates to his painting Pygmalion and Galatea (c. 1890). He created both painted and sculpted versions of the myth, depicting the moment the sculptor Pygmalion's statue comes to life. His sculptures often explored classical themes or figures derived from his paintings. He experimented with materials and techniques, notably reviving the ancient practice of polychromy – tinting marble to achieve more lifelike effects, as seen in works like Tanagra (1890). His sculptural output further demonstrated his versatility and his deep engagement with the classical tradition across different media.

A Master's Atelier: Gérôme as Teacher

Beyond his own artistic production, Gérôme was one of the most influential art educators of his time. Appointed a professor at the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts in Paris in 1864, he taught there for nearly forty years, shaping generations of artists. His atelier was highly sought after, attracting students from France and across the globe, particularly from the United States.

Gérôme was known as a demanding but respected teacher. Accounts from students, such as the American painter Douglas Volk (who later became a notable sculptor himself), describe his rigorous methods, emphasizing strong draftsmanship, anatomical accuracy, and the importance of a highly finished surface – the hallmarks of his own Academic style. He insisted on mastery of fundamentals before allowing students greater freedom.

Despite his own conservative artistic stance, his atelier produced artists who went on to develop remarkably diverse styles. Among his most famous pupils were the American Impressionist Mary Cassatt, the pioneering American realist Thomas Eakins, the Symbolist painter Odilon Redon, the American painter J. Alden Weir, and the French cartoonist Georges Ferdinand Bigot, known for his work in Japan. Other students included Oswald Van Houten. This diverse output suggests that while Gérôme imparted technical discipline, his students ultimately forged their own artistic paths, sometimes reacting against, rather than simply imitating, their master. His long teaching career solidified his central position within the official French art establishment. His influence also extended through friendships, such as his relationship with the sculptor Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux. Some sources also note the influence of writers like Paul Adam on his circle or thinking.

Artistic Style and Method

Jean-Léon Gérôme's style is synonymous with 19th-century French Academicism at its most polished. His work is characterized by meticulous attention to detail, often based on extensive research, sketches, and, significantly, photographs. Gérôme was an early adopter of photography, using it not as a direct source to copy but as an invaluable reference tool for capturing details of architecture, landscapes, and figures, particularly during his travels. This contributed to the sense of sharp-focus realism in his paintings.

His technique involved careful preparatory drawings, precise underpainting, and the application of smooth, blended layers of paint, resulting in a highly finished surface (the fini) where brushstrokes are often invisible. This emphasis on finish and detail was a hallmark of the Academic tradition, contrasting sharply with the looser brushwork and emphasis on light and fleeting moments favored by the Impressionists. His compositions are typically well-structured, often theatrical or staged, designed to present a clear narrative or capture a dramatic moment. His use of color could be vibrant, especially in his Orientalist scenes, but always controlled within a framework of realistic representation. Linearity, influenced by Ingres, remained a strong element in his definition of form.

Controversy and Criticism

Gérôme's career was marked by significant controversy, particularly concerning his relationship with modern art and the nature of his Orientalist depictions. As a pillar of the Academic establishment and a powerful professor at the École des Beaux-Arts, Gérôme became one of the most vocal and influential opponents of Impressionism and subsequent avant-garde movements. He viewed the Impressionists' style – with its visible brushwork, emphasis on subjective perception, and scenes of modern life – as a degradation of artistic standards and an insult to the traditions of French painting. He famously used his influence to try and block the acceptance of Impressionist works, such as those by Claude Monet or Édouard Manet, into state collections or prestigious exhibitions like the Salon. This staunch conservatism earned him the enmity of many modernist artists and critics.

His Orientalist works, while immensely popular in his time, faced increasing scrutiny in the later 20th and 21st centuries. Post-colonial critics, influenced by thinkers like Edward Said, argued that Gérôme's depictions, despite their surface realism, often perpetuated harmful stereotypes of Middle Eastern and North African peoples as exotic, sensual, lazy, or violent. Works like The Snake Charmer and The Slave Market were singled out for presenting staged, often eroticized scenes that reflected Western colonial attitudes and fantasies more than the complex realities of the cultures depicted. While acknowledging his technical skill and the visual richness of these paintings, critics pointed to a problematic "colonial gaze" that objectified his subjects.

Furthermore, even during his lifetime, some critics found his meticulous realism could feel cold or overly staged, prioritizing archaeological accuracy or anecdotal detail over deeper emotional resonance, as noted with The Age of Augustus. His immense popular success and the wide reproduction of his works through engravings and photographs also led to accusations of commercialism, suggesting he catered to popular taste rather than pursuing purely artistic ideals.

Later Years and Enduring Legacy

Jean-Léon Gérôme remained active as an artist well into his later years, continuing to paint and sculpt. He maintained his prominent position in the French art world, receiving numerous honors, although his artistic style was increasingly seen as outdated by the turn of the century with the rise of Post-Impressionism and Fauvism. He died in his Paris studio on January 10, 1904, reportedly found deceased in front of a portrait of Rembrandt, working until the very end.

Following his death, Gérôme's reputation suffered a significant decline during the dominance of modernism in the early and mid-20th century. Academic art in general fell out of critical favor, dismissed as overly sentimental, technically obsessed, and irrelevant to modern concerns. His opposition to Impressionism further tarnished his image in narratives that championed the avant-garde.

However, the late 20th and early 21st centuries saw a scholarly and popular reappraisal of Gérôme and Academic art. Museums began exhibiting his work more prominently, and art historians undertook more nuanced assessments of his career, acknowledging his technical brilliance, his role as an educator, and the historical significance of his work, even while engaging with the problematic aspects of his Orientalism.

Perhaps one of Gérôme's most unexpected legacies lies in his influence on popular culture, particularly cinema. His painting Pollice Verso (Thumbs Down), depicting gladiators in the Roman Colosseum awaiting the crowd's verdict, directly inspired director Ridley Scott during the making of the blockbuster film Gladiator (2000). Scott famously showed producers a reproduction of the painting to convey the world he wanted to create. Gérôme's dramatic compositions, historical settings, and detailed realism provided a visual template for epic filmmaking. His work has also reportedly influenced the aesthetic of video games like the Assassin's Creed series, demonstrating a continued resonance in visual storytelling.

Conclusion: A Complex Figure in Art History

Jean-Léon Gérôme remains a figure of considerable complexity in art history. He was undeniably a master technician, a dominant force within the 19th-century French Academic system, and an influential teacher who shaped a generation of artists. His historical, mythological, and particularly his Orientalist paintings achieved enormous popularity and defined a specific mode of highly finished, detailed realism.

At the same time, he stands as a symbol of resistance to artistic innovation, his fierce opposition to Impressionism marking a major fault line in the art world of his era. Furthermore, his Orientalist works, while visually captivating, are now viewed through a critical lens that acknowledges their role in shaping and perpetuating Western stereotypes of the East. His legacy is thus twofold: that of a celebrated Academic master whose influence extended even into 21st-century popular culture, and that of a controversial figure whose work continues to provoke debate about representation, tradition, and artistic change. He remains an essential artist for understanding the dynamics and contradictions of art in the 19th century.