Léon Bonhomme (1870-1924) was a French painter whose career unfolded during a period of extraordinary artistic ferment in Paris. While perhaps not as globally renowned as some of his contemporaries who spearheaded revolutionary movements, Bonhomme carved out a distinct niche for himself with his sensitive portrayals of women, intimate interior scenes, and a subtle, nuanced approach to color and light. His work offers a valuable window into the private worlds and the evolving social fabric of the Belle Époque and the early twentieth century.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born in 1870, Léon Bonhomme emerged as an artist in an era where Paris was the undisputed capital of the art world. The city throbbed with innovation, with Impressionism having already shattered academic conventions, and new movements like Post-Impressionism, Symbolism, and Fauvism beginning to take shape. It was in this vibrant atmosphere that Bonhomme sought his artistic education, a crucial step for any aspiring painter of the time.

He was fortunate to study under two of the most influential, albeit stylistically divergent, figures in late 19th-century French art: Jean-Léon Gérôme and Gustave Moreau. Gérôme, a towering figure of academic art, was renowned for his meticulously detailed historical and Orientalist paintings. From Gérôme, Bonhomme would have absorbed a rigorous training in draughtsmanship, anatomical precision, and the classical principles of composition. This foundational academic grounding provided him with a technical mastery that would underpin his later, more personal explorations.

In stark contrast to Gérôme's academicism was Gustave Moreau, a Symbolist painter whose studio at the École des Beaux-Arts became a crucible for a generation of artists who would later define modern art. Moreau was an inspirational teacher, encouraging his students to develop their individual voices and explore the expressive potential of color. His pupils included such future luminaries as Henri Matisse, Albert Marquet, Georges Rouault, and Charles Camoin, who would go on to form the core of the Fauvist movement. While Bonhomme did not embrace the radical colorism of the Fauves, Moreau's emphasis on personal expression and the emotional power of art undoubtedly left a mark on his development.

This dual tutelage provided Bonhomme with a rich and somewhat paradoxical artistic inheritance: the discipline of the academy combined with the imaginative freedom encouraged by Symbolism. This blend allowed him to navigate the complex art scene of his time, drawing from tradition while forging his own path.

Artistic Style and Influences

Léon Bonhomme's style is often characterized by its intimacy and psychological depth, particularly in his depictions of women. He moved away from the grand historical or mythological themes favored by the Academy, and also eschewed the radical formal experiments of the avant-garde. Instead, he found his voice in the quiet observation of everyday life, focusing on personal moments and interior spaces. His work shares affinities with the Intimist movement, exemplified by painters like Pierre Bonnard and Édouard Vuillard, who also focused on domestic scenes imbued with a sense of warmth, quietude, and emotional resonance.

While Bonnard and Vuillard often dissolved forms into tapestries of color and pattern, Bonhomme generally retained a more solid sense of form, likely a legacy of his academic training. However, his application of paint could be fluid and expressive, and his palette, though often subdued, was capable of great subtlety and richness. He was adept at capturing the play of light in an interior, the texture of fabric, and the nuanced expressions of his sitters.

The influence of Post-Impressionist painters can also be discerned in his work. Artists like Edgar Degas, with his candid portrayals of women at their toilette or in moments of unguarded intimacy, certainly provided a precedent for Bonhomme's subject matter. The emphasis on capturing the essential character of a subject, rather than merely a superficial likeness, also aligns with the broader Post-Impressionist ethos. One might also see a distant echo of the sensitive figure painting of Auguste Renoir, though Bonhomme's approach was generally less idealized and more introspective.

Bonhomme's paintings often evoke a sense of quiet contemplation. His figures are rarely engaged in dramatic action; instead, they are often shown reading, resting, or lost in thought. This focus on the inner life of his subjects gives his work a timeless quality, inviting viewers to connect with the human emotions portrayed.

Key Themes and Subjects

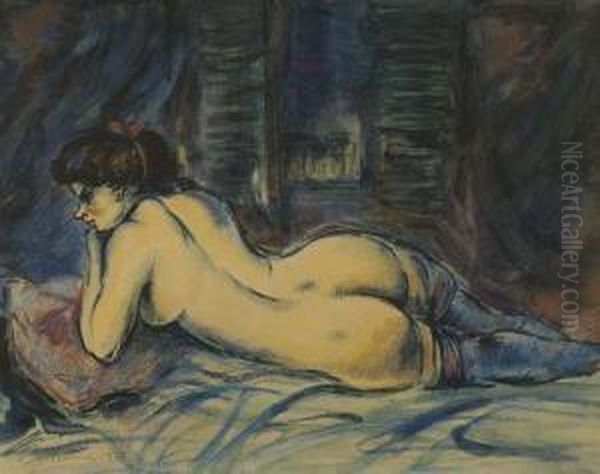

The dominant theme in Léon Bonhomme's oeuvre is the portrayal of women in intimate settings. He painted numerous scenes of women at their toilette, in their boudoirs, or simply relaxing in domestic interiors. These were not typically the idealized nudes of academic tradition, nor the overtly sensual figures found in some contemporary art. Instead, Bonhomme's women often appear natural, unposed, and absorbed in their own worlds. Works such as "Femme à sa toilette" or "Jeune femme se coiffant" exemplify this focus.

His nudes, while acknowledging the tradition, are often characterized by a sense of vulnerability and introspection rather than overt eroticism. He explored the female form with a sensitivity that emphasized its grace and humanity. The settings are usually simple, allowing the focus to remain on the figure and the subtle interplay of light and shadow on skin and fabric.

Portraits also formed a significant part of his output. He painted men, women, and children, often capturing a sense of their personality and social standing through pose, attire, and expression. These portraits are typically straightforward and unpretentious, aiming for a truthful representation rather than flattery. He seemed particularly adept at capturing the innocence and charm of children.

Beyond figures, Bonhomme also painted still lifes and occasional landscapes, though these are less central to his reputation. His interior scenes, even those without figures, often convey a strong sense of human presence, as if the inhabitants have just stepped out of the room. He paid careful attention to the details of domestic life – furniture, fabrics, decorative objects – using them to create atmosphere and suggest the character of the occupants.

Representative Works

While a comprehensive catalogue raisonné might be elusive for an artist like Bonhomme who operated somewhat outside the major avant-garde narratives, several works are frequently cited as representative of his style and thematic concerns.

"La Toilette" (The Dressing Table) is a recurring theme and title for Bonhomme, appearing in various compositions. These paintings typically depict a woman before her mirror, engaged in the rituals of grooming. They are intimate glimpses into a private world, rendered with sensitivity to the play of light on skin and the textures of clothing and domestic objects. The mood is often one of quiet introspection.

"Nu couché" (Reclining Nude) is another subject he revisited. These works showcase his ability to render the female form with both anatomical understanding and a sense of grace. Unlike the more academic or overtly provocative nudes of some of his contemporaries, Bonhomme's nudes often possess a quiet dignity and naturalness.

"Jeune femme lisant" (Young Woman Reading) captures a common motif of the era, reflecting increased literacy and the quiet pursuits of bourgeois life. Such paintings emphasize the interiority of the subject, lost in the world of a book, and allow the artist to explore the subtleties of light and domestic atmosphere.

His portraits, such as "Portrait de Madame H." or "Portrait d'enfant," demonstrate his skill in capturing a likeness while also conveying something of the sitter's personality. These works are often characterized by a directness of gaze and a careful rendering of features and attire.

The titles of his works are often simple and descriptive, reflecting his focus on the everyday: "Intérieur," "Femme au miroir," "Le Repos." Each of these suggests a commitment to observing and rendering the unpretentious moments of life.

Exhibitions and Recognition

Léon Bonhomme, like most artists of his time seeking to build a career, regularly submitted his works to the major Parisian Salons. These annual exhibitions were crucial venues for artists to gain visibility, attract patrons, and receive critical attention. He exhibited at the Salon des Artistes Français, which was the more traditional of the major Salons, having succeeded the official Paris Salon. His participation here indicates his connection to the established art world and his mastery of academic techniques.

He also exhibited at the Salon d'Automne and the Salon des Indépendants. The Salon d'Automne, established in 1903, was known for being more progressive and was famously the venue where Fauvism burst onto the scene in 1905. The Salon des Indépendants, founded in 1884 with the motto "sans jury ni récompense" (without jury nor awards), was a vital platform for avant-garde artists who were often rejected by the more conservative Salons. Bonhomme's presence in these more forward-thinking venues suggests his engagement with contemporary artistic currents and his desire to be seen alongside a broader range of artists.

While he may not have achieved the revolutionary fame of a Picasso or the widespread popularity of a Monet, Bonhomme was a respected painter within the Parisian art scene. His work would have been known to fellow artists, critics, and a circle of collectors who appreciated his particular brand of intimate realism and sensitive portraiture. The very act of consistently exhibiting across different Salons points to a dedicated professional artist actively engaged in the art world of his day.

Context and Contemporaries

To fully appreciate Léon Bonhomme's contribution, it is essential to place him within the rich tapestry of the Parisian art world of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. This was an era of unprecedented artistic diversity and rapid change.

His teachers, Gérôme and Moreau, represent two significant poles of artistic thought. Gérôme's other students included Thomas Eakins, an American realist, and Frederick Arthur Bridgman. Moreau's studio, as mentioned, was a hotbed for future Fauves like Matisse, Marquet, Rouault, Camoin, and also artists like Henri Manguin and Jean Puy. Bonhomme would have interacted with these emerging talents, sharing ideas and witnessing firsthand the development of new artistic languages.

His affinity with the Intimists places him in the company of Pierre Bonnard and Édouard Vuillard. These artists, associated with the Nabis group (which also included Maurice Denis and Félix Vallotton), sought to create art that was decorative, symbolic, and deeply personal, often focusing on the quiet beauty of domestic life. While Bonhomme was not formally a Nabi, his thematic concerns and his emphasis on atmosphere and emotion align with their sensibilities.

The broader Post-Impressionist landscape included giants like Paul Cézanne, whose structural approach to composition was transforming painting; Vincent van Gogh, with his intense emotional expression and vibrant color; and Paul Gauguin, who sought a more primitive and symbolic art. While Bonhomme's style was less radical, he operated in a world shaped by their innovations.

Other contemporaries whose work might offer points of comparison or contrast include:

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, who chronicled the demimonde of Paris with a sharp, graphic style.

James McNeill Whistler, whose tonal harmonies and aestheticism influenced many, particularly in portraiture and mood pieces.

John Singer Sargent, an expatriate American whose dazzling society portraits captured the glamour of the era.

Mary Cassatt, an American Impressionist living in Paris, known for her tender depictions of mothers and children, a theme that Bonhomme also touched upon.

Gustave Caillebotte, an Impressionist whose depictions of modern Parisian life and domestic interiors also offer interesting parallels.

Jean Béraud, who specialized in painting scenes of Parisian daily life and high society with a detailed, almost photographic realism.

Bonhomme's art can be seen as a quieter, more personal counterpoint to some of the more bombastic or revolutionary movements of his time. He represents a strand of French painting that valued subtlety, technical skill, and the depiction of human emotion within familiar settings.

Legacy and Later Appreciation

Léon Bonhomme's legacy is that of a skilled and sensitive painter who contributed to the rich tradition of French figurative art at a time of significant transition. While the grand narratives of art history often focus on the most radical innovators, artists like Bonhomme play a crucial role in providing a fuller picture of the artistic landscape. They represent the many talented individuals who absorbed the influences of their time, honed their craft, and produced work of lasting quality and appeal.

His paintings continue to be appreciated for their technical accomplishment, their psychological insight, and their evocative portrayal of an era. They offer a more intimate and less sensationalized view of Parisian life than that provided by some of his more famous contemporaries. His focus on the private lives of women, rendered with empathy and respect, provides a valuable perspective.

In recent decades, there has been a growing interest in artists who operated somewhat outside the main avant-garde movements, leading to a re-evaluation of figures like Bonhomme. His work can be found in private collections and occasionally appears in art auctions, where it is valued for its charm, intimacy, and skillful execution. Art historians and enthusiasts of the Belle Époque and early 20th-century French art recognize his contribution to the genre of intimate interior scenes and portraiture.

His connection to Gustave Moreau's studio also lends him historical significance, as he was part of a generation that received guidance from one of the most forward-thinking teachers of the period. While he forged a different path than the Fauves, his training there undoubtedly broadened his artistic horizons.

Conclusion

Léon Bonhomme was an artist who found beauty and meaning in the quiet corners of life. His paintings of women, interiors, and portraits are characterized by a subtle realism, a sensitivity to mood and atmosphere, and a deep respect for his subjects. Trained in the academic tradition yet responsive to the newer currents of his time, he developed a personal style that emphasized intimacy and psychological depth.

While he may not have instigated an artistic revolution, Léon Bonhomme was a dedicated and talented painter whose work enriches our understanding of French art in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. He stands as a testament to the enduring power of figurative painting to capture the nuances of human experience and the spirit of an age. His art invites us into a world of quiet contemplation, offering a gentle and insightful vision that continues to resonate with viewers today. His contribution, though perhaps modest when compared to the titans of modernism, is a valuable part of the diverse artistic heritage of Paris during one of its most vibrant periods.