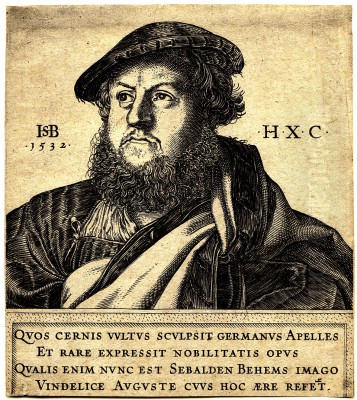

Hans Sebald Beham stands as one of the most prolific and technically gifted printmakers of the German Renaissance. Born in Nuremberg in 1500, his life spanned a tumultuous period of artistic innovation and religious upheaval. Beham belonged to a group of artists known as the "Little Masters" (Kleinmeister), celebrated for their small-format, exquisitely detailed engravings and woodcuts. Though deeply influenced by the towering figure of Albrecht Dürer, Beham forged his own distinct path, creating a vast body of work that explored religious narratives, classical mythology, contemporary peasant life, and intricate ornamentation. His career, however, was marked by controversy, including expulsion from his native city for his radical beliefs. He eventually settled in Frankfurt, where he worked tirelessly until his death on November 22, 1550.

Nuremberg Beginnings and Early Influences

Nuremberg, at the turn of the 16th century, was a vibrant center of art, craft, and intellectual life in the Holy Roman Empire. It was the city of Albrecht Dürer, whose workshop and prints set an unparalleled standard for artistic excellence and technical innovation across Northern Europe. It was into this stimulating environment that Hans Sebald Beham was born. His younger brother, Barthel Beham, born two years later, would also become a significant printmaker among the Little Masters.

While the exact nature of Hans Sebald's training remains undocumented, the pervasive influence of Dürer is undeniable in his early work. The precision of line, the sophisticated handling of form and volume, and the engagement with both traditional religious themes and newer humanist interests echo the master's style. However, there is no concrete evidence to suggest that Beham, or his brother Barthel, ever formally apprenticed in Dürer's workshop. It is more likely that they, like many aspiring artists of their generation, absorbed Dürer's techniques and compositions through the widespread circulation of his prints. Another contemporary Nuremberg artist, Georg Pencz, often associated with the Beham brothers, also developed his skills within this Dürer-dominated milieu.

The "Godless Painters" Controversy

Beham's early career in Nuremberg was dramatically interrupted in 1525. This was a period of intense religious and social turmoil, fueled by the nascent Protestant Reformation initiated by Martin Luther and the widespread unrest culminating in the German Peasants' War. Beham, along with his brother Barthel and Georg Pencz, was brought before the Nuremberg city council and accused of heresy, blasphemy, and challenging civic authority.

The specific charges reportedly included denying the transubstantiation (the Catholic doctrine of the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist), questioning the validity of baptism, and expressing disbelief in scripture. Their radical views, possibly influenced by more extreme reformers like Thomas Müntzer or Andreas Karlstadt, placed them far outside the bounds of even the Lutheranism that Nuremberg was cautiously adopting. Labelled the "godless painters" (gottlosen Maler), the three artists were expelled from the city in January 1525. This event highlights the dangerous intersection of art, religion, and politics during the Reformation, where artistic expression could be interpreted as seditious dissent. Although the ban was lifted later that year, the incident marked a turning point for Beham.

Plagiarism Accusation and Departure from Nuremberg

Further controversy followed. In 1528, Hans Sebald Beham faced another serious accusation, this time concerning artistic integrity. He published a book titled Dises buchlein zeyget an und lernet ein mass oder proporcion der Ross (This little book shows and teaches a measurement or proportion of horses). This publication appeared shortly after Albrecht Dürer's death and dealt with a subject – equine proportions – that Dürer himself had extensively researched for his own planned treatise on human and animal proportion.

Beham was accused of plagiarizing Dürer's unpublished preparatory drawings and notes. Dürer's monumental work on human proportion, Vier Bücher von Menschlicher Proportion (Four Books on Human Proportion), was published posthumously that same year (1528). The accusation that Beham had illicitly used Dürer's material on horses, possibly obtained during Dürer's lifetime or immediately after his death, led to Beham being forced to leave Nuremberg once again. This incident further strained his relationship with the city authorities and likely contributed to his decision to seek his fortune elsewhere.

Frankfurt: A New Center of Activity

After periods spent in other cities, possibly including Ingolstadt and Munich where his brother Barthel found patronage, Hans Sebald Beham eventually settled in the thriving commercial city of Frankfurt am Main around 1532. Frankfurt offered a more tolerant atmosphere and a robust market for printed materials. It was here that Beham would spend the remainder of his life, establishing himself as an independent and remarkably productive master.

In Frankfurt, Beham operated not just as an artist but also as his own publisher, maintaining control over the production and distribution of his prints. This entrepreneurial approach allowed him a degree of artistic freedom. He produced an astonishing number of works: approximately 252 engravings, 18 etchings, and around 1500 woodcuts. Many of these woodcuts were created as book illustrations, collaborating with Frankfurt printers like Christian Egenolff. His prints found a ready market among the German bourgeoisie – merchants, scholars, and collectors who appreciated their technical brilliance, diverse subject matter, and often convenient small size.

Artistic Style and Technical Mastery

Hans Sebald Beham is renowned for his mastery of printmaking techniques, particularly engraving and woodcut. His association with the "Little Masters" reflects the predominantly small scale of his engravings. These miniature works, often no larger than a postage stamp, are characterized by incredible precision and detail. Beham possessed an exceptional control of the burin, the sharp tool used for engraving copper plates. He could render complex scenes, textures, and anatomical details with astonishing clarity on a minute scale.

His woodcuts, while often larger than his engravings, also display remarkable skill. He adapted his style effectively to the different demands of the woodblock, using clear, strong lines for narrative clarity, particularly in his book illustrations. While Dürer remained a foundational influence, Beham's style evolved. He absorbed aspects of the Italian Renaissance, likely through prints by artists such as Marcantonio Raimondi, who popularized Raphael's designs. This Italian influence can be seen in his handling of classical subjects, his interest in anatomical accuracy, and a certain robustness in his figure types. Some scholars also note potential stylistic dialogues with contemporaries like Lucas Cranach the Elder or Hans Holbein the Younger, particularly in portraiture and the depiction of textures.

Diverse Themes and Subjects

Beham's vast output covered an exceptionally wide range of themes, reflecting the diverse interests of his time and his varied clientele.

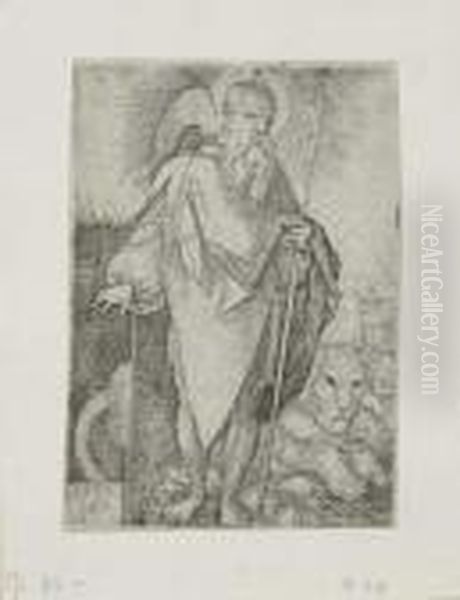

Religious Subjects: Despite his early religious controversies, Beham produced numerous prints depicting scenes from the Old and New Testaments. His series on the Passion of Christ and the Parable of the Prodigal Son were popular. He also created images of individual saints, such as St. Matthias or St. Jerome. These works often combined traditional iconography with his characteristic attention to detail and lively characterization.

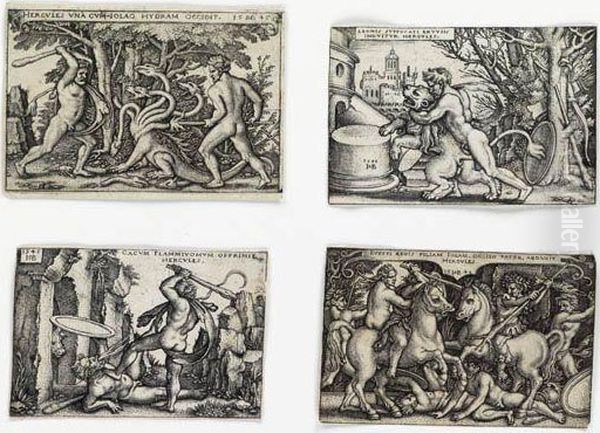

Mythology and Antiquity: Reflecting the humanist interests of the Renaissance, Beham frequently turned to classical mythology and ancient history. He engraved series depicting the Labors of Hercules, scenes with gods and goddesses like Jupiter, Venus, and Saturn, and images of satyrs and nymphs, such as the Satyr Woman Playing a Flute. These works allowed him to explore the nude figure and dynamic compositions.

Genre Scenes and Peasant Life: Beham is particularly famous for his depictions of contemporary peasant life. Works like his Peasant Festival series or individual prints showing dancers, drinkers, and village brawls are rendered with energy and often a satirical edge. While sometimes humorous, these scenes also offer valuable insights into the social realities and popular culture of 16th-century Germany. Prints like Two Fools tap into a long tradition of moralizing satire.

Allegory and Ornament: He also produced allegorical prints representing virtues, vices, or abstract concepts like The Impossible (depicting tasks like washing a Moor white). Furthermore, Beham was a master of ornamental design, creating intricate patterns and friezes that were influential for artisans working in other media, such as furniture makers, goldsmiths, and architects.

Book Illustration: His work as a book illustrator was significant. He provided woodcuts for various publications, including Bibles, historical texts, and practical manuals. His illustrations for the Bibliographia Historica (1539) are a notable example of his contribution to Frankfurt publishing.

Other Works: Beham's versatility extended to designs for playing cards, stained glass, wallpapers, and coats of arms, demonstrating the broad application of printmaking skills in the Renaissance.

Beham, the Reformation, and Social Commentary

Hans Sebald Beham's art cannot be fully understood apart from the context of the Protestant Reformation. His expulsion from Nuremberg in 1525 was a direct result of his radical religious and possibly social views. While he later produced conventional religious prints, some of his works carry clear Reformation-era commentary, often critical of the established Church.

His woodcut The Descent of the Pope into Hell, showing devils gleefully dragging a pontiff into the inferno, is a potent piece of anti-papal propaganda, echoing themes found in the polemical prints of Lucas Cranach the Elder, Martin Luther's primary artist. Similarly, works depicting peasant life, while perhaps intended for urban amusement, sometimes carried undertones sympathetic to the peasantry or critical of social hierarchies, especially when viewed against the backdrop of the Peasants' War. Prints like Christ and the Sheep Shed have been interpreted as reflecting the reformers' critique of church corruption and aligning Christ with the common people. Beham's prints, easily reproducible and distributable, served as effective vehicles for disseminating ideas, whether religious, political, or satirical, to a wider audience.

The Little Masters

Hans Sebald Beham, his brother Barthel, and Georg Pencz form the core of the Nuremberg "Little Masters." The term, coined later by art historians, refers primarily to the small scale of their engravings, though it also implicitly acknowledges their position in the generation following the "great masters" like Dürer. Other artists sometimes associated with this group or working in a similar vein include Heinrich Aldegrever from Westphalia and Albrecht Altdorfer of the Danube School, though Altdorfer also worked on a larger scale and in painting.

The Little Masters specialized in highly detailed prints intended for collectors who would appreciate their technical virtuosity and often sophisticated subject matter within an intimate format. They catered to a growing market of educated middle-class patrons and fellow artists who assembled albums of prints. Their work bridged the gap between monumental art and decorative craft, popularizing classical and humanist themes alongside traditional religious and genre subjects. Beham was arguably the most prolific and versatile among them.

Influence and Legacy

Hans Sebald Beham was highly successful during his lifetime. His prints circulated widely throughout Germany and beyond, influencing subsequent generations of printmakers. His technical skill set a high standard, and his thematic innovations, particularly in genre scenes and ornamentation, were widely copied and adapted. Artists like Virgil Solis and Jost Amman, who ran large printmaking workshops in Nuremberg and Frankfurt later in the 16th century, clearly built upon the foundations laid by Beham and the other Little Masters.

His depictions of peasant life contributed significantly to the development of genre imagery in Northern European art. His ornamental designs were incorporated into pattern books used by craftsmen across various fields. Though perhaps overshadowed in popular imagination by Albrecht Dürer or Lucas Cranach, Beham's immense output and technical brilliance secure his place as a major figure in the history of printmaking. His works are preserved in major print rooms worldwide, valued for their artistry, their historical insights, and their embodiment of the dynamic spirit of the German Renaissance. Artists like Simon Bening, working in manuscript illumination, explored miniature formats in a different medium but shared the Renaissance fascination with detailed observation evident in Beham's prints. The portability and accessibility of prints, exemplified by Beham's work and even earlier illustrated books like the Hypnerotomachia Poliphili, were crucial for the dissemination of Renaissance styles and ideas across Europe.

Representative Works

While Beham produced thousands of prints, certain works and series stand out:

The Peasant Festival Series (c. 1535-1539): A lively set of engravings and woodcuts depicting various aspects of village celebrations, full of dancing, drinking, and boisterous activity.

The Labors of Hercules (c. 1542-1548): A series of engravings showcasing Beham's engagement with classical mythology and his skill in depicting the nude male figure in action.

The Passion of Christ (various dates): Several series in both engraving and woodcut, demonstrating his handling of traditional religious narrative. Individual prints like Ecce Homo are powerful examples.

The Impossible (c. 1549): An engraving depicting various proverbial impossibilities, showcasing his wit and engagement with popular sayings.

Ornamental Prints: Numerous designs featuring intricate foliage, classical motifs, and grotesque figures, highly influential in decorative arts.

The Standard Bearer and the Drummer (c. 1544): A dynamic engraving capturing the martial spirit of the time.

Conclusion

Hans Sebald Beham was a pivotal figure in 16th-century German art. Born in the shadow of Dürer, he navigated the turbulent waters of the Reformation and emerged as a master printmaker in his own right. His technical virtuosity, particularly in the demanding medium of engraving on a small scale, remains astonishing. His prolific output covered an immense range of subjects, from profound religious scenes and classical myths to earthy depictions of peasant life and intricate ornamental designs. Despite controversies that forced him from his native Nuremberg, he built a successful career in Frankfurt, becoming a key member of the "Little Masters" and influencing generations of artists and craftsmen. Beham's work provides a rich visual record of his time, capturing the artistic innovations, religious fervor, social tensions, and humanist learning of the German Renaissance.