Maerten Jacobsz van Heemskerck (1498–1574) stands as a pivotal figure in the art of the Northern Renaissance, a Dutch painter and print designer whose career exemplifies the transformative impact of Italian art on Northern European traditions. Born in the village of Heemskerk in North Holland, from which he derived his name, he rose from humble beginnings as a farmer's son to become one of the most respected and influential artists of his time. His extensive oeuvre, encompassing portraits, religious narratives, mythological scenes, and designs for engravings, showcases a dynamic fusion of meticulous Netherlandish realism with the grandeur and idealism of the Italian High Renaissance and burgeoning Mannerism.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Maerten Jacobsz was born in 1498. His father, Jacob Willemsz van Veen, was a farmer, and initially, young Maerten was expected to follow in his father's footsteps. However, he displayed an early and fervent passion for drawing, a calling that clashed with his father's practical expectations. According to Karel van Mander, the early art historian whose Schilder-boeck (Book of Painters) of 1604 provides much of our biographical information on Heemskerck, the young artist faced considerable paternal opposition.

Driven by an unyielding desire to pursue art, Heemskerck eventually left his rural home. One anecdote tells of him fleeing, undertaking a significant journey on foot to Delft, a testament to his determination. His initial artistic instruction came from Cornelis Willemsz in Haarlem, not The Hague as sometimes stated, a painter of local repute. He then moved to Delft to study with Jan Lucasz, a lesser-known master who likely provided him with foundational skills. These early apprenticeships would have grounded him in the prevailing Netherlandish artistic traditions, characterized by detailed observation and a rich, oil-based technique.

The most significant formative influence in his early Dutch period was undoubtedly Jan van Scorel. Around 1527-1529, Heemskerck became a pupil or assistant to Scorel in Haarlem. Scorel himself had recently returned from an extensive journey through Germany, Austria, and, crucially, Italy, including Rome and Venice. He was one of the first Dutch artists to fully absorb and disseminate the principles of the Italian Renaissance in the North, earning him the title of a "Romanist." Under Scorel, Heemskerck was exposed to this new, classicizing visual language, which emphasized anatomical accuracy, harmonious composition, and the depiction of idealized human forms inspired by classical antiquity and masters like Raphael and Michelangelo.

The Pivotal Journey to Rome

The allure of Italy, and particularly Rome, the heart of classical antiquity and the High Renaissance, was irresistible for ambitious Northern artists. In 1532, Heemskerck embarked on his own journey south, a pilgrimage that would profoundly shape his artistic vision. He remained in Rome for approximately four to five years, until 1536 or 1537. This period was not one of formal tutelage under a single master but rather an intensive immersion in the artistic wonders of the city.

Heemskerck dedicated himself to studying and sketching the ruins of ancient Rome – the Colosseum, the Forum, triumphal arches, and classical sculptures like the Belvedere Torso, the Laocoön group, and the Apollo Belvedere. Two of his sketchbooks from this period survive (now primarily in the Kupferstichkabinett, Berlin), filled with meticulous drawings of these ancient monuments, as well as contemporary Roman architecture and sculptures. These sketchbooks are invaluable, not only as a record of Heemskerck's studies but also as historical documents depicting Rome before later transformations.

Beyond antiquity, Heemskerck absorbed the lessons of the Italian High Renaissance masters. He studied the works of Raphael, particularly his frescoes in the Vatican Stanze, admiring their compositional clarity and graceful figures. Even more impactful was his encounter with the art of Michelangelo Buonarroti. The powerful, muscular nudes of the Sistine Chapel ceiling and Michelangelo's sculptures deeply impressed Heemskerck, influencing his subsequent treatment of the human form, imbuing it with a new monumentality and dynamism. He is also said to have interacted with contemporary artists in Rome, possibly including Giulio Romano, Raphael's principal pupil and a key figure in the development of Mannerism.

This Roman sojourn was transformative. Heemskerck assimilated the Italianate vocabulary of heroic figures, complex poses, dramatic compositions, and classical architectural settings. He learned to depict the human body with greater anatomical understanding and expressive power, moving beyond the more restrained and linear style typical of earlier Netherlandish art.

Return to Haarlem and Mature Career

Upon his return to the Netherlands around 1537, Heemskerck settled in Haarlem, which was then a thriving artistic center. He quickly established himself as a leading painter, his Italian experiences lending his work a sophisticated and modern air that was highly sought after. He became a prominent member of the Haarlem Guild of St. Luke, the professional organization for painters and other craftsmen, eventually serving as its dean or chairman on multiple occasions, a testament to his standing among his peers.

Heemskerck was a prolific artist, undertaking a wide range of commissions. He painted numerous altarpieces for churches in Haarlem, Delft, Alkmaar, and Amsterdam. These religious works often featured complex, multi-figured compositions, dramatic narratives, and a rich, vibrant palette. His figures, while retaining a certain Northern particularity, displayed the muscularity and dynamic postures learned in Italy.

In addition to large-scale religious works, Heemskerck was a highly accomplished portraitist. His portraits are characterized by their sharp psychological insight, meticulous rendering of textures and details (a hallmark of Netherlandish tradition), and often incorporate symbolic elements or classical allusions that speak to the sitter's status or learning. One notable example is the Family Portrait of Pieter Jan Foppesz (c. 1530, though likely later if Foppesz was a wealthy pastor, as some sources suggest, and the Italian influence is strong), considered an early and important example of the Dutch group portrait genre. He also painted a striking Self-Portrait with the Colosseum (1553), which proudly displays his Roman experiences and artistic identity.

Heemskerck's personal life included two marriages. His first wife, Marie Jacobsdr de Coninck, died in childbirth shortly after their marriage. His second wife was Marytgen Gerritsdr. Despite his artistic success and civic roles, including being appointed priest of the chapel of St. Bavo's Church in Haarlem in 1540 (a lay position often held by respected citizens), his later years were touched by the religious and political turmoil of the Reformation and the Dutch Revolt. During the Spanish siege of Haarlem in 1572-73, Heemskerck, then an elderly man, temporarily sought refuge in Amsterdam. He returned to Haarlem after the siege and died there on October 1, 1574, at the age of 76. He was buried in the St. Bavo's Church.

Artistic Style and Influences

Heemskerck's style is a fascinating synthesis of Northern and Southern European artistic currents. From his Netherlandish heritage, he retained a love for meticulous detail, rich textures, and a certain earthy realism, especially in his portraits. However, his Italian sojourn fundamentally reshaped his approach to composition, figure drawing, and narrative expression.

The influence of Michelangelo is particularly evident in Heemskerck's treatment of the human body. His figures often display exaggerated musculature, contorted poses (figura serpentinata), and a sense of heroic grandeur. This can be seen in his depictions of saints, biblical heroes, and mythological figures. Raphael's influence is discernible in the clarity of his compositions and the sometimes graceful arrangement of figures, though Heemskerck's temperament leaned more towards the dramatic and forceful.

Heemskerck is often categorized as a "Romanist," a term applied to Northern artists who traveled to Rome and incorporated Italian Renaissance and Mannerist elements into their work. Other notable Romanists include Jan Gossaert (Mabuse), Bernard van Orley, Frans Floris, and Lambert Lombard, who, like Heemskerck, played crucial roles in transforming the artistic landscape of the Low Countries. Heemskerck's style, particularly in his later works, shows distinct Mannerist tendencies: elongated proportions, artificial elegance, complex spatial arrangements, and a heightened emotional intensity.

His use of color was often bold and vibrant, sometimes with sharp contrasts that added to the drama of his scenes. His draftsmanship was strong and confident, evident in his preparatory drawings and the designs he created for prints. He was adept at conveying complex narratives and allegories, often packing his compositions with figures and symbolic details that invited close scrutiny and intellectual engagement.

Key Themes and Subject Matter

Heemskerck's oeuvre spans a wide range of subjects, reflecting the diverse demands of his patrons and the intellectual currents of his time.

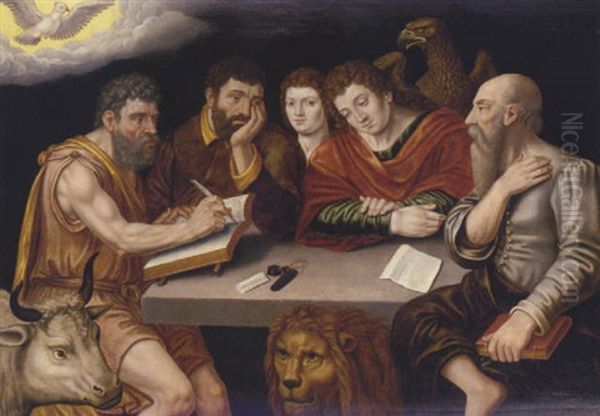

Religious Paintings: A significant portion of his output consisted of religious works, including large altarpieces and smaller devotional panels. He depicted scenes from both the Old and New Testaments, such as the Lamentation of Christ, The Crucifixion, The Adoration of the Magi, and scenes from the lives of saints. His St. Luke Painting the Virgin (c. 1532, and later versions) is a notable example of a theme popular among artists, as St. Luke was their patron saint. These works often combined intense piety with dramatic visual storytelling. The Reformation brought challenges, with periods of iconoclasm leading to the destruction of much religious art. Heemskerck, however, continued to receive commissions for religious subjects, adapting to changing theological emphases where necessary.

Mythological and Allegorical Scenes: Reflecting the Renaissance interest in classical antiquity and humanism, Heemskerck also painted mythological subjects, such as Venus and Cupid or scenes from Ovid's Metamorphoses. He also created allegorical works, personifying virtues, vices, or abstract concepts, often with complex iconographies that appealed to a learned audience.

Portraits: As mentioned, Heemskerck was a skilled portraitist. His sitters included wealthy merchants, clerics, and scholars. These portraits are valuable not only as likenesses but also as cultural documents, reflecting the status, aspirations, and intellectual interests of the Dutch elite in the 16th century. His self-portraits, like the one with the Colosseum, are particularly revealing of his artistic self-consciousness.

Print Designs: Heemskerck was exceptionally prolific as a designer of prints. While he did not typically engrave the plates himself, he supplied numerous drawings to be translated into engravings and woodcuts by skilled printmakers such as Dirck Volkertsz Coornhert, Philip Galle, Cornelis Bos, and Hieronymus Cock, the latter being a major publisher in Antwerp. These prints covered a vast array of subjects: biblical narratives, allegories, mythological scenes, personifications of virtues and vices, and series like The Seven Wonders of the World, The Victories of Charles V, and The Story of the Prodigal Son.

Notable Works

Identifying a few "representative" works from such a vast and varied output is challenging, but several stand out for their artistic quality, historical significance, or influence.

Sketchbooks from Rome (c. 1532-1536): While not finished artworks in the traditional sense, these drawings (Kupferstichkabinett, Berlin) are crucial. They document ancient Roman monuments, many of which have since changed or disappeared, and reveal Heemskerck's intensive study process. They are a primary source for understanding the impact of Rome on Northern artists.

_St. Luke Painting the Virgin_ (versions from c. 1532, Frans Hals Museum, Haarlem; and later, e.g., Rennes): This subject allowed Heemskerck to reflect on the nature of art and the status of the artist. The Haarlem version, possibly painted shortly before or during his Italian trip, already shows an interest in classical forms, while later versions are more overtly Italianate.

_The Seven Wonders of the World_ (print series, designed c. 1570-1572, engraved by Philip Galle): This series of engravings became immensely popular and widely disseminated, shaping the popular imagination of these ancient marvels for centuries. Each print combines archaeological fantasy with dynamic compositions.

_The Brazen Serpent_ (c. 1550-1555): This painting showcases Heemskerck's ability to handle complex, multi-figure compositions with dramatic intensity, reflecting Michelangelo's influence in the muscular, contorted figures.

_Self-Portrait with the Colosseum_ (1553, Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge): A powerful statement of artistic identity, where Heemskerck presents himself as a learned artist, with the iconic Roman ruin in the background signifying his classical education and artistic lineage. The trompe-l'oeil cartellino with his name and date adds to the sophisticated presentation.

_Lamentation Triptych_ (c. 1559-1560, Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam): Originally commissioned for the Great Church in Delft, this large altarpiece is a mature work demonstrating his mastery of dramatic religious narrative, rich color, and complex figural arrangements, blending Northern emotional intensity with Italianate forms.

_Momus Criticizing the Gods_ (c. 1561, Gemäldegalerie, Berlin): This mythological scene, depicting the god of criticism finding fault with the creations of other gods, is a complex allegory that showcases Heemskerck's engagement with classical literature and his ability to create dynamic, Mannerist compositions.

The Printmaker's Impact

Heemskerck's significance as a designer for the burgeoning print market cannot be overstated. In the 16th century, engravings and woodcuts became a powerful medium for disseminating images and ideas across Europe. Heemskerck was one of the most prolific and sought-after designers for this market. His drawings were translated into prints by leading engravers of the day, including the aforementioned Dirck Coornhert, Philip Galle, and Cornelis Bos, and published by influential figures like Hieronymus Cock in Antwerp.

These prints covered an astonishing range of subjects. Biblical cycles, such as the Story of Tobias or the Acts of the Apostles, were popular. Allegorical series, like the Triumph of Patience or the Vices and Virtues, catered to a taste for moralizing and didactic imagery. His depictions of The Seven Wonders of the World or The Victories of Emperor Charles V had broad appeal.

The widespread circulation of these prints meant that Heemskerck's compositions and stylistic innovations reached a far larger audience than his paintings alone ever could. They influenced other artists not only in the Netherlands but also in Germany, France, and beyond. Artists like Karel van Mander himself, Hendrick Goltzius, and later even Rembrandt van Rijn would have been familiar with Heemskerck's printed work. The prints served as models for compositions, figure types, and iconographic schemes, contributing significantly to the visual culture of the late Renaissance and early Baroque periods.

Contemporaries and Artistic Milieu

Heemskerck operated within a vibrant and competitive artistic environment. His primary teacher in the Italianate style, Jan van Scorel, remained a significant figure in Haarlem and Utrecht. While they shared a common interest in Italian art, their styles diverged, with Scorel often favoring a more harmonious, Raphaelesque classicism, while Heemskerck leaned towards a more robust, Michelangelesque and Mannerist drama. There was likely a degree of professional rivalry, but also mutual respect.

In Haarlem, Heemskerck would have known other painters, though few matched his international reputation. The printmaking scene, however, connected him to a wider network. His collaboration with engravers like Coornhert and Galle was crucial. Hieronymus Cock's publishing house in Antwerp, "At the Four Winds," was a major hub, disseminating prints by Heemskerck alongside those of Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Frans Floris, and Lambert Lombard, among others. This network facilitated the exchange of artistic ideas across the Low Countries.

Further afield, artists like Anthonis Mor (Antonio Moro) of Utrecht achieved international fame as a portraitist in a style that, while distinct, shared the Netherlandish attention to detail combined with a new monumentality. In Antwerp, Frans Floris was a leading Romanist whose large workshop produced numerous mythological and religious paintings in a highly Italianate, often Michelangelesque, style. While Heemskerck was primarily based in Haarlem, the artistic currents of Antwerp, the dominant economic and cultural center of the Low Countries at the time, would have been well known to him. The influence of earlier Netherlandish masters like Jan Gossaert, who was one of the very first to bring Italian Renaissance motifs north, also formed part of the artistic backdrop.

Later Years and Legacy

The latter part of Heemskerck's career coincided with increasing religious and political instability. The Protestant Reformation gained traction in the Netherlands, leading to tensions and eventually the Iconoclastic Fury of 1566, when Calvinist mobs destroyed vast quantities of religious art in churches. This profoundly impacted artistic production, with commissions for traditional Catholic altarpieces declining in some areas. Heemskerck, however, continued to work, adapting to the changing climate. His later religious works sometimes reflect a more austere or didactic tone.

Despite these challenges, Heemskerck remained a respected and successful artist until his death in 1574. He was known for his diligence and thrift, amassing a considerable estate. His will included provisions for a dowry to be awarded annually to a deserving young couple at his graveside, a tradition that reportedly continued for some time.

Heemskerck's legacy is substantial. He was a key figure in the Romanist movement, successfully integrating Italian Renaissance and Mannerist principles into Netherlandish art without entirely sacrificing its native character. His powerful figure style, dramatic compositions, and innovative iconography influenced a generation of artists in the Northern Netherlands, including Hendrick Goltzius and Cornelis Cornelisz van Haarlem, who further developed the Mannerist style. Through his widely circulated prints, his influence extended even further, contributing to the broader European visual language of the late 16th and early 17th centuries.

His works are now found in major museums worldwide, including the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, the Frans Hals Museum in Haarlem, the Gemäldegalerie in Berlin, the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, and the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen in Rotterdam, as well as numerous prestigious print collections.

Conclusion

Maerten van Heemskerck was more than just a painter; he was an artistic innovator, a bridge between cultures, and a prolific visual storyteller. His journey from a Dutch farming village to the heart of ancient and Renaissance Rome, and his subsequent career as a leading master in Haarlem, encapsulate the ambition and intellectual curiosity of the Renaissance artist. By skillfully blending the meticulous realism of his Netherlandish heritage with the heroic grandeur and dynamic forms of Italian art, Heemskerck forged a powerful and influential personal style. His paintings and, perhaps even more significantly, his designs for prints left an indelible mark on the art of Northern Europe, securing his place as one of the most important Dutch artists of the 16th century.