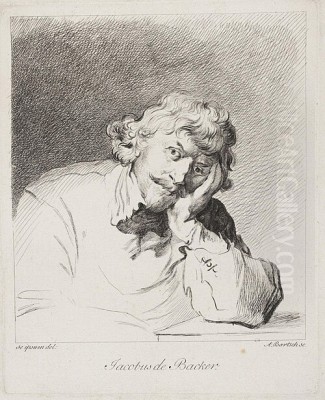

Jacob de Backer stands as a fascinating yet partially obscured figure in the rich tapestry of 16th-century Flemish art. Active in the bustling artistic hub of Antwerp during the latter half of the century, he emerged as a significant proponent of the Mannerist style, skillfully blending Northern traditions with the powerful influence of the Italian Renaissance. Despite a tragically short life, De Backer left behind a considerable body of work characterized by complex compositions, sophisticated allegories, and a distinctive stylistic flair. However, the scarcity of documented biographical details means that much about his life and the precise extent of his personal artistic output remains shrouded in mystery, inviting ongoing scholarly investigation and debate. This exploration delves into the known aspects of Jacob de Backer's life, examines the defining characteristics of his art, highlights his key works, and considers his position within the vibrant artistic milieu of late Renaissance Antwerp.

Unraveling a Mysterious Biography

The historical record concerning Jacob de Backer is frustratingly sparse, leaving art historians to piece together his life story from limited sources and educated conjecture. It is generally accepted that he was active as a painter and draughtsman primarily in Antwerp. His birth year is estimated to be around 1555, and his death is believed to have occurred around 1585. This timeline suggests a career that spanned perhaps only a decade, cut short when the artist was merely about thirty years old. This brevity undoubtedly contributes to the lack of extensive contemporary documentation about his life and activities.

Some early accounts, though not definitively proven, offer intriguing glimpses into his formative years. One narrative suggests he might have been abandoned by his father during childhood, a detail that adds a layer of pathos to his obscure origins. Regarding his artistic training, tradition holds that he may have initially studied in the workshop of Antonio van Palermo, an artist of Sicilian origin active in Antwerp. Subsequently, he is thought to have entered the studio of Hendrick van Steenwijk the Elder, a painter known for his architectural perspectives. These connections, if accurate, would have placed De Backer within established Antwerp artistic circles, providing him access to skills, techniques, and stylistic trends prevalent in the city. However, the speculative nature of these biographical fragments must be acknowledged.

The Influence of Italy and the Mannerist Idiom

Jacob de Backer's artistic style firmly places him within the Mannerist movement that swept across Europe following the High Renaissance. His work demonstrates a profound engagement with Italian artistic developments, particularly the styles emanating from Florence and Rome. The influence of Giorgio Vasari, the Italian painter, architect, and art historian, is frequently cited as particularly significant in shaping De Backer's approach. This Italianate leaning is evident in numerous aspects of his paintings.

De Backer's figures often display the elongated proportions, elegant S-curve postures (figura serpentinata), and complex, sometimes artificial, poses characteristic of Mannerism. His compositions tend to be crowded and dynamic, filled with figures interacting in intricate spatial arrangements that prioritize artistic invention over naturalistic representation. Furthermore, his color palette can be vibrant and sophisticated, sometimes employing the acidic hues and striking contrasts favored by Mannerist painters seeking heightened emotional and visual impact.

An intriguing question is whether De Backer ever traveled to Italy himself to absorb these influences firsthand. While his art is saturated with Italianate motifs and stylistic devices, there is currently no documentary evidence confirming such a journey. It is entirely plausible that he assimilated these trends through the circulation of Italian prints and drawings, which were widely available in Antwerp, a major center for printing and publishing. Additionally, interactions with other Netherlandish artists who had traveled south, such as Frans Floris or Maarten de Vos, could have provided crucial exposure to Italian Mannerist principles without requiring De Backer to leave Antwerp.

Themes and Subject Matter

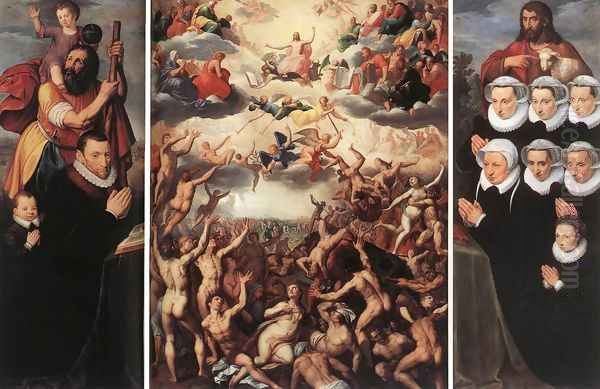

The thematic repertoire of Jacob de Backer aligns closely with the preferences of the Mannerist era and the demands of his patrons. His oeuvre is rich in religious narratives, drawing extensively from both the Old and New Testaments. Subjects such as the Last Judgement, various scenes from the life of Christ, and episodes involving Old Testament figures appear frequently in works attributed to him and his workshop. These religious paintings often provided opportunities to depict dramatic events and explore complex theological ideas.

Alongside religious themes, De Backer engaged with classical mythology, portraying stories of gods, goddesses, and heroes from Greco-Roman antiquity. Scenes like Venus and Adonis, Diana and Actaeon, or the Judgement of Paris allowed for the depiction of the nude human form, a central preoccupation of Renaissance and Mannerist art. These mythological subjects often carried allegorical meanings, exploring themes of love, beauty, fate, and divine power.

Perhaps most characteristic of his intellectual inclinations are his complex allegorical paintings. These works visually interpret abstract concepts, virtues, vices, or elements. De Backer excelled in creating intricate visual puzzles laden with symbolism, requiring viewers to decipher the intended meaning. His skill in rendering the human figure, often in dynamic and anatomically sophisticated poses, was central to his ability to convey these elaborate religious, mythological, and allegorical narratives effectively.

The "Seven Deadly Sins" and Other Key Works

Among the most celebrated works associated with Jacob de Backer is the series depicting the "Seven Deadly Sins." This group of paintings exemplifies his engagement with complex allegorical themes and showcases his Mannerist style. Historical records indicate that a series representing the Sins, attributed to De Backer, was acquired in Antwerp by Cosimo Masi, secretary to Alessandro Farnese, Duke of Parma, in 1594, some years after the artist's presumed death. These works were sent to Parma. Following confiscation in 1611, they eventually made their way to Naples and are now housed in the prestigious Museo di Capodimonte.

While direct examination reveals variations suggesting workshop participation, the "Seven Deadly Sins" series is crucial for understanding the De Backer corpus. These paintings likely featured elaborate compositions, personified representations of each sin (Pride, Greed, Lust, Envy, Gluttony, Wrath, and Sloth), and the sophisticated, slightly artificial elegance typical of his style. The series reflects a common theme in Northern European art, treated here with a distinctly Italianate Mannerist vocabulary.

Beyond this famous series, numerous other works are attributed to De Backer or his circle. These include large-scale compositions like "The Last Judgement," allegories of the "Four Elements" or the "Four Seasons," and various mythological scenes. While the specific attribution of many individual pieces remains debated, the collective body of work points to a highly productive artist or studio specializing in intellectually demanding and visually elaborate paintings catering to the sophisticated tastes of Antwerp's clientele.

The Attribution Conundrum: De Backer and His Workshop

One of the most significant challenges in studying Jacob de Backer is the issue of attribution. The substantial number of paintings associated with his name, coupled with their stylistic diversity and sometimes uneven quality, has led scholars to question the extent of his personal involvement in every piece. It is widely suspected that De Backer operated a large and efficient workshop. This workshop likely employed assistants who helped produce paintings in the master's style, contributing to the large output achieved during his relatively short period of activity.

This situation makes it difficult to definitively separate the "autograph" works executed entirely by De Backer's own hand from those produced collaboratively or entirely by workshop members following his designs or models. Some art historians have even proposed that "Jacob de Backer" might function more as a label for a specific stylistic production originating from a workshop, possibly even one that continued to operate after his death, rather than solely representing the output of a single individual.

The variations in quality and the presence of different "sub-styles" within the De Backer corpus lend credence to the workshop theory. Some paintings exhibit exceptional refinement and invention, while others appear more routine or standardized in their execution. This attribution conundrum means that assessing De Backer's individual artistic genius requires careful stylistic analysis and a nuanced understanding of 16th-century workshop practices. He may have been as much an influential workshop director as a solitary creator.

Contemporaries and Artistic Context in Antwerp

To fully appreciate Jacob de Backer's contribution, it is essential to place him within the vibrant artistic context of late 16th-century Antwerp. Despite political and religious turmoil, Antwerp remained a major European center for art production and trade. De Backer worked during a period dominated by the legacy of earlier masters like Frans Floris, whose large workshop and Italianate style had profoundly impacted Flemish painting.

De Backer's contemporaries included a host of talented artists. Maarten de Vos was another highly prolific painter active in Antwerp, known for his religious and mythological works, also heavily influenced by Italian art, particularly Venetian painting. Otto van Veen, who would later become Peter Paul Rubens's teacher, was establishing his career during De Backer's later years, bridging the gap between Mannerism and the emerging Baroque.

The Francken dynasty of painters, including figures like Ambrosius Francken the Elder and Hieronymus Francken I (though the latter worked mainly in France), were also active, contributing to the city's artistic output, often specializing in smaller-scale cabinet pictures but also tackling larger commissions. Crispijn van den Broeck was another contemporary active as both a painter and a designer of prints and stained glass, working in a Mannerist style. Furthermore, Hendrick de Clerck, though based primarily in Brussels, worked in a related late Mannerist style.

The influence of his supposed masters, Antonio van Palermo and Hendrick van Steenwijk the Elder, must also be considered part of his immediate artistic environment. Beyond painters, the publishing houses of Antwerp, such as the one run by Hieronymus Cock or later Philips Galle, played a crucial role in disseminating artistic styles, including Italian Mannerism, through engravings and etchings. De Backer operated within this dynamic network of influence, competition, and collaboration, absorbing Italian trends while contributing to the specific character of Antwerp Mannerism. The aforementioned Giorgio Vasari, though Italian, was a significant intellectual contemporary whose influence was felt strongly in Antwerp.

Legacy and Art Historical Significance

Despite the uncertainties surrounding his biography and the precise boundaries of his oeuvre, Jacob de Backer holds a recognized place in the history of Flemish art. He is considered an important representative of the late Mannerist style in the Southern Netherlands, active during the period between the dominance of Frans Floris and the advent of the Baroque revolution led by Rubens. His significance lies primarily in his role as a conduit and adapter of Italian Mannerist principles for an Antwerp audience.

His works, whether autograph or workshop productions, demonstrate a high level of technical skill, compositional ingenuity, and intellectual depth. The complex allegories and dynamic narratives found in the De Backer corpus catered to the sophisticated tastes of patrons who appreciated intricate symbolism and stylistic elegance. The sheer volume of work associated with his name suggests that his style was popular and influential, likely impacting other artists through the activities of his workshop.

While his early death prevented him from developing his style further or achieving the long-lasting fame of artists like Rubens, Jacob de Backer remains a key figure for understanding the specific character of painting in Antwerp during the late 16th century. His art reflects the international connections of the city, its engagement with dominant European artistic trends, and its capacity for producing visually stunning and intellectually engaging works. The enduring mystery surrounding his life only adds to the intrigue of this talented, prolific, yet enigmatic master of Antwerp Mannerism.