Hans von Marées (1837-1887) stands as a unique and somewhat enigmatic figure in the landscape of 19th-century German art. A painter who spent the most artistically significant part of his life in Italy, he sought a synthesis of classical ideals with a modern sensibility, striving for a monumental and timeless quality in his work. Though not widely acclaimed during his lifetime, his posthumous influence, particularly on early 20th-century German modernists, cemented his position as a pivotal artist. His oeuvre, characterized by its intellectual depth, formal rigor, and often melancholic beauty, continues to invite contemplation and study.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening in Germany

Born on December 24, 1837, in Elberfeld, then part of the Prussian Rhine Province, Hans von Marées hailed from a family with a mixed heritage; his paternal grandfather was of French Huguenot descent, and his mother's family was German. His father, a respected chamber of commerce president, moved the family to Koblenz, where young Hans received his early education. His artistic inclinations became apparent early on, leading him to Berlin in 1854 to pursue formal training.

In Berlin, Marées enrolled at the prestigious Academy of Arts and became a student of the history and battle painter Karl Steffek (also known as Carl Steffek). Steffek, a competent academician, would have instilled in Marées the foundational skills of drawing and composition prevalent at the time. During this period, Marées also undertook military service in 1855. His early works from this Berlin period, though few survive or are well-documented, likely reflected the prevailing academic realism, perhaps with a romantic undercurrent typical of German art of the era. He would have been exposed to the works of influential German painters like those of the Düsseldorf school of painting, known for its detailed landscapes and narrative scenes, and the historical paintings of artists like Peter von Cornelius and Wilhelm von Kaulbach, who were part of an earlier generation that had also sought inspiration in Italy.

The Lure of Italy: A New Artistic Horizon

The pivotal moment in Marées's early career came in 1864. Like many German artists before and after him, from Albrecht Dürer to the Nazarenes, Marées felt the magnetic pull of Italy, the cradle of classical antiquity and the Renaissance. His journey south was facilitated by a commission from the discerning art collector and patron Count Adolf Friedrich von Schack. Schack, based in Munich, was building a significant collection and often commissioned artists to create copies of Old Master paintings for his gallery, the Schackgalerie.

Marées was tasked, alongside his contemporary Franz von Lenbach, who would later become a celebrated portrait painter in Munich, to travel to Italy and Spain to copy works by masters such as Titian, Velázquez, and Raphael. This undertaking was not merely a mechanical exercise; it was an immersive education. For Marées, direct engagement with the masterpieces of the past was transformative. He absorbed the lessons of Renaissance composition, the richness of Venetian color, and the dignity of classical form. While Lenbach excelled in faithful reproductions and quickly gained favor, Marées's approach was more interpretive, seeking to understand the underlying principles rather than just the surface appearance. This period marked the beginning of his lifelong artistic dialogue with the classical tradition. He would spend the majority of the next two decades in Italy, primarily in Rome and later in Naples and Florence.

The Roman Circle: Friendships and Intellectual Ferment

Rome, for Marées, was not just a repository of ancient art but a vibrant center of artistic and intellectual life. He became part of the community of "Deutsch-Römer" (German-Romans), artists and scholars who found in the Eternal City a more congenial atmosphere for their classical and idealist aspirations than in rapidly industrializing Germany. Two relationships formed during this period were particularly crucial to his personal and artistic development: his friendships with the art theorist Konrad Fiedler and the sculptor Adolf von Hildebrand.

Konrad Fiedler (1841-1895) was a wealthy philosopher and art historian who became one of Marées's most important patrons and intellectual companions. Fiedler's theories on art emphasized the autonomy of the visual, arguing that art was a distinct form of knowledge concerned with pure visibility and form, rather than mimesis or narrative content. This resonated deeply with Marées's own evolving artistic aims. Together, in 1869, Marées and Fiedler embarked on a significant journey, visiting Spain, France, and the Netherlands. This trip exposed Marées to a wider range of European art, including the works of Spanish masters like Velázquez (whom he had copied for Schack) and Dutch painters like Rembrandt, further enriching his visual vocabulary.

Adolf von Hildebrand (1847-1921) was a younger sculptor who arrived in Rome in 1866 and quickly formed a close bond with Marées. Their relationship was one of intense artistic camaraderie and mutual influence. Marées, the elder and more established painter, acted as a mentor figure to Hildebrand. They shared a studio for a time and engaged in profound discussions about the nature of art and form. Hildebrand himself would later become a highly influential sculptor and theorist, publishing "Das Problem der Form in der bildenden Kunst" (The Problem of Form in Painting and Sculpture) in 1893, a text that echoed some of the formal concerns he had explored with Marées and Fiedler. The intensity of their friendship is palpable in Marées's portraits of Hildebrand and in group compositions that include him. While some later interpretations have suggested homoerotic undertones in Marées's depictions of the male nude, often linked to his close male friendships, the primary documented nature of his bond with Hildebrand was one of profound artistic and intellectual kinship. The earlier, erroneous anecdotal claims regarding Hildebrand's supposed suicide and Marées marrying his widow are unfounded; Hildebrand lived a long and productive life, marrying Irene Schellhauss in 1877.

Other German artists active in Italy during this period, forming the broader context of Marées's milieu, included painters like Anselm Feuerbach and Arnold Böcklin. Feuerbach, like Marées, pursued a classicizing ideal, though with a more overtly melancholic and literary bent. Böcklin, on the other hand, developed a highly personal form of Symbolism, often drawing on mythological themes but imbuing them with a unique, sometimes unsettling atmosphere. While Marées's path was distinct, he shared with these artists a commitment to figural art and a search for meaning beyond mere naturalism, contrasting with the burgeoning Impressionist movement in France.

The Naples Frescoes: A Monumental Vision

The most significant public commission of Marées's career, and arguably one of his crowning achievements, came in 1873. He was invited by the German zoologist Anton Dohrn to decorate the library of the newly founded Stazione Zoologica (Zoological Station) in Naples. This marine biology research institute, housed in a classical-style building in the Villa Comunale, became the site for a remarkable cycle of frescoes.

Working alongside Adolf von Hildebrand, who contributed sculptural elements, Marées created a series of monumental wall paintings depicting scenes related to the sea and the lives of the local people. These frescoes are not straightforward genre scenes but rather idealized visions of humanity in harmony with nature. Works like The Rowers, Fishermen Setting Out, Pergola (Company at the Table), and Orange Grove (The Gatherers) evoke a timeless, almost Arcadian world. The figures, often powerful and statuesque, are rendered with a simplified grandeur. The compositions are carefully structured, emphasizing rhythm and balance, and the colors, though somewhat muted by time, possess a distinctive clarity.

The Naples frescoes represent a culmination of Marées's artistic ideals: the integration of the human figure into a landscape, the pursuit of monumental form, and the evocation of a serene, ordered existence. They are considered among the most important examples of German mural painting in the 19th century, standing apart from the more academic or historicist frescoes common at the time. They reflect Marées's deep study of Italian Renaissance fresco cycles, particularly those of Raphael, yet they possess a distinctly modern sensibility in their formal simplification and psychological depth. The figures in Pergola, for instance, include portraits of Marées himself, Hildebrand, and Fiedler, grounding the idealized scene in personal reality.

Artistic Style and Philosophy: The Search for Pure Form

Hans von Marées's artistic style is complex and not easily categorized. It evolved from an early realism towards a more idealized and symbolic mode of expression, deeply informed by his study of classical and Renaissance art, yet always striving for a personal vision.

Idealism and the Human Figure: At the core of Marées's art was the human figure, which he saw as the primary vehicle for expressing universal ideas and emotions. He sought to depict not the fleeting moment or individual peculiarity, but the enduring, archetypal human form. His figures, often nude or classically draped, possess a sculptural quality and a sense of quiet dignity. This idealism connected him to a lineage of German artists who looked to classical antiquity as a model, but Marées's figures often carry a weight of introspection and a subtle melancholy that is distinctly his own.

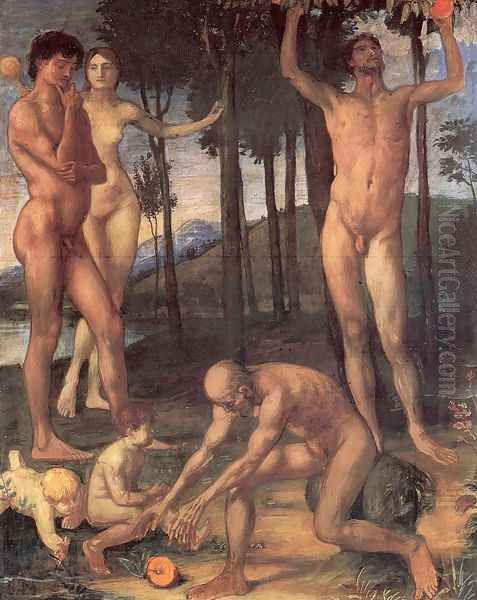

Mythology, Allegory, and the "Golden Age": Marées frequently turned to mythological and allegorical themes, but he reinterpreted them in a highly personal way. Works like The Hesperides (a triptych existing in several versions), The Ages of Man, and The Golden Age are not mere illustrations of ancient myths but rather meditations on fundamental aspects of human existence: life, death, love, and the search for an ideal state of being. He envisioned a "Golden Age," an Arcadia where humanity lived in simple harmony with nature, a theme that resonated with a certain romantic anti-modernism present in some intellectual circles of the time.

Influence of Antiquity and the Renaissance: Marées's immersion in Italian art was profound. He admired the clarity and order of Greek sculpture, the harmonious compositions of Raphael, the monumentality of Michelangelo, and the rich color of Titian. However, he was not a slavish imitator. He sought to internalize the principles of these masters and apply them to his own artistic concerns, aiming for a "great style" that was both timeless and relevant to his own era. His technique, particularly in his later oil paintings, often involved building up layers of color, creating a rich, somewhat dry surface that emphasized form and structure over illusionistic detail.

Formal Concerns: Composition, Color, and Rhythm: Influenced by his discussions with Fiedler, Marées became increasingly preoccupied with the formal aspects of painting. He believed that a painting's meaning resided not just in its subject matter but in its inherent visual structure: the arrangement of forms, the play of color, the creation of rhythm and harmony. His compositions are often carefully balanced, with figures arranged in frieze-like arrangements or in stable, pyramidal groups. His color palette, while capable of richness, often tended towards muted, earthy tones, with a focus on tonal relationships to define form and space. He was less interested in the optical effects of light that preoccupied the French Impressionists like Claude Monet or Camille Pissarro, and more focused on the plastic, tactile qualities of form.

Key Works and Enduring Themes

Beyond the Naples frescoes, Marées produced a significant body of work, including portraits, mythological compositions, and figure studies.

Self-Portraits: Marées painted numerous self-portraits throughout his career, offering intimate glimpses into his psyche. These are often characterized by their searching intensity and a sense of profound introspection. The Self-Portrait with Yellow Hat (1874), for example, shows the artist with a direct, almost confrontational gaze, yet with an underlying vulnerability. These works reveal a man deeply committed to his artistic vision, perhaps also aware of his isolation from contemporary artistic trends.

Mythological and Allegorical Triptychs: The triptych format, with its historical and religious connotations, appealed to Marées for his large-scale allegorical statements. The Hesperides triptych (versions from 1879-80 and 1884-87) depicts the mythical guardians of the golden apples in a serene, timeless landscape. The figures are monumental and idealized, embodying a sense of classical calm. The Ages of Man (c. 1877-78) is another significant triptych, exploring the cycle of human life through a series of symbolic figures. These works aimed for a universal significance, transcending specific historical or narrative contexts.

Figure Compositions and Studies: Marées was fascinated by the human body in motion and at rest. Works like The Rowers (oil versions related to the Naples frescoes), Men by the Sea, and numerous studies of bathers and riders explore the figure in landscape settings. These compositions often feature male nudes, rendered with an emphasis on their anatomical structure and rhythmic arrangement. Dragonslayer (St. George) is another powerful example, reinterpreting a traditional theme with a focus on the dynamic interplay of forms. His Portrait of Philip IV of Spain as a Hunter (1865), likely a study or reinterpretation after Velázquez, shows his early engagement with Old Masters.

Drawings: Marées was a prolific draftsman. His drawings, often in pencil, chalk, or ink, reveal his working process and his constant exploration of form and composition. They range from quick sketches to highly finished studies and are essential to understanding the development of his ideas.

Later Years, Solitude, and Unfulfilled Ambitions

Despite the artistic success of the Naples frescoes, Marées did not receive further large-scale public commissions. He continued to live and work in Italy, primarily in Rome, supported by Fiedler and a small circle of admirers. His later years were marked by a degree of isolation and perhaps a sense of unfulfilled ambition. He struggled with ill health and financial difficulties. He remained dedicated to his artistic ideals, working on large, complex compositions that often remained unfinished or were developed through multiple versions.

His pursuit of a "great style" and his rejection of prevailing academic and market-driven trends meant that he remained a marginal figure in the contemporary art world. While artists like Adolph Menzel dominated the Berlin art scene with his historical realism, and the Munich Secession was beginning to challenge academic conservatism with artists like Franz von Stuck (who also explored mythological themes but with a more decadent, fin-de-siècle sensibility), Marées remained committed to his solitary path in Italy. He died relatively young, at the age of 49 (not 50 as sometimes stated, given his birth and death dates), on June 5, 1887, in Rome. He was buried in the Protestant Cemetery in Rome, the final resting place for many foreign artists and writers, including Keats and Shelley.

Legacy and Posthumous Recognition

During his lifetime, Hans von Marées was known and appreciated by only a select few. However, his reputation began to grow in the early 20th century, largely thanks to the efforts of critics like Julius Meier-Graefe, who championed his work and recognized its importance for modern art. A major retrospective exhibition in Munich in 1908-1909 brought his work to a wider audience and had a significant impact on a younger generation of German artists.

Artists of the German Expressionist movement, such as Franz Marc and August Macke (both of Der Blaue Reiter group), found inspiration in Marées's emphasis on spiritual content, his use of color for expressive purposes (though Marées's palette was generally more subdued), and his search for a harmonious union of humanity and nature. Paul Klee also acknowledged Marées's influence. Later artists, including Max Beckmann, with his powerful triptychs and monumental figures, and Karl Hofer, who also sought a modern classicism, can be seen as part of a lineage that includes Marées. His dedication to formal structure and his intellectual approach to art also resonated with Bauhaus ideals, even if his subject matter was different.

His works are now primarily housed in German museums, notably the Neue Pinakothek in Munich (which holds a significant collection, including The Hesperides and self-portraits) and the Alte Nationalgalerie in Berlin. The Naples frescoes remain in situ at the Stazione Zoologica.

Conclusion: An Artist of Enduring Significance

Hans von Marées remains a compelling figure in art history. He was an artist out of step with many of the dominant trends of his time, yet his unwavering pursuit of an ideal art, his synthesis of classical tradition and modern feeling, and his profound exploration of the human form give his work an enduring power. He sought to create an art that was monumental, timeless, and imbued with intellectual and spiritual depth. While he may not have achieved widespread fame during his life, his legacy as a "German Roman" who forged a unique path between idealism and modernity, and his influence on subsequent generations of artists, secure his place as a significant contributor to the rich tapestry of European art. His quest for an art of "pure visibility" and essential form continues to speak to those who seek meaning beyond the surface of things.