Vincenzo Gemito stands as one of Italy's most compelling and individualistic sculptors of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Born into the vibrant, chaotic, and often impoverished streets of Naples, Gemito's life and art were inextricably linked to his native city. His work, characterized by an astonishing realism, a profound empathy for his subjects, and a deep reverence for classical antiquity, captured the essence of Neapolitan life with an intensity rarely matched. From street urchins to celebrated figures, Gemito's sculptures and drawings offer a poignant window into a world of hardship, resilience, and enduring beauty. His journey from a foundling to an internationally acclaimed artist, marked by periods of intense creativity and profound personal struggle, makes him a fascinating figure in the annals of art history.

A Child of Naples: Early Life and Formative Influences

Vincenzo Gemito was born on July 16, 1852, in Naples. His origins were humble and tinged with sorrow; he was abandoned as an infant on the steps of the Dell'Annunziata orphanage. Shortly thereafter, he was adopted by a poor artisan family. His adoptive mother had recently lost her own child, and it is said that the name "Gemito," meaning "groan" or "moan," was given to him in remembrance of her grief, a name that would eerily foreshadow the undercurrent of pathos in much of his work.

Growing up in the bustling, poverty-stricken quarters of Naples, the young Gemito was immersed in a world teeming with life. The city's streets, with their fishermen, street vendors, playful children, and weary laborers, became his first and most enduring classroom. He displayed an early aptitude for drawing and modeling, and his raw talent did not go unnoticed. Though largely self-taught in his initial years, his innate ability to capture form and emotion was undeniable.

His formal artistic training began tentatively. He spent a brief period in the studio of the sculptor Emanuele Caggiano, and later, more significantly, he frequented the studio of Stanislao Lista. Lista, a respected painter and sculptor, recognized Gemito's prodigious talent and provided him with guidance. However, Gemito's spirit was fiercely independent, and he was more inclined to learn from direct observation and his study of masterworks than from rigid academic instruction. The Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Naples, with its structured curriculum, held little appeal for him, though he did attend some classes.

The nearby National Archaeological Museum in Naples, housing one of_the world's finest collections of Greek and Roman antiquities, became a far more influential source of inspiration. Gemito was captivated by the naturalism, dynamism, and idealized beauty of classical sculpture, particularly Hellenistic works. This early exposure to the art of antiquity would profoundly shape his artistic vision, creating a unique tension and fusion with the gritty realism of his chosen subjects.

The Emergence of a Unique Talent

By his teenage years, Gemito was already producing works of remarkable maturity and skill. At the tender age of 16, in 1868, he created one of his first significant pieces, The Card Player (Il Giocatore). This terracotta sculpture, depicting a young street boy engrossed in a game, showcased his extraordinary ability to capture a fleeting moment with astonishing realism and psychological insight. The work was exhibited at the Promotrice di Belle Arti in Naples and was met with acclaim, a remarkable achievement for such a young, largely self-taught artist.

This early success spurred him on. Gemito continued to draw his subjects from the everyday life of Naples. He was particularly drawn to the scugnizzi, the street urchins of Naples, whose vivacity, cunning, and vulnerability he rendered with unparalleled empathy. Works from this period, such as his terracotta and bronze figures of young fishermen and street boys, solidified his reputation as a rising star of the Neapolitan school of realism. This movement, often referred to as Verismo in Italy, sought to depict contemporary social realities with unvarnished truth, and Gemito was at its forefront in sculpture.

He formed close friendships with other like-minded artists in Naples, most notably the painter Antonio Mancini. Mancini, like Gemito, was dedicated to portraying the life of the common people with raw honesty. Together with other artists such as Francesco Paolo Michetti, they formed a circle that challenged academic conventions and championed a more direct, observational approach to art. Their shared commitment to realism, combined with their individual talents, made Naples an exciting hub of artistic innovation during this period. The influence of earlier Neapolitan masters, such as the painter Domenico Morelli, who, while not strictly a Verist, had paved the way for a more emotionally charged and realistic depiction of historical and religious subjects, also lingered in the artistic atmosphere of the city.

Parisian Sojourn and International Recognition

In the 1870s, Gemito's ambition and growing reputation led him to seek broader horizons. He traveled to Paris, then the undisputed capital of the art world. He arrived in 1877, accompanied by his friend Antonio Mancini. Paris offered new opportunities and challenges. Gemito established a studio and quickly immersed himself in the city's vibrant artistic milieu.

His work soon attracted attention at the prestigious Paris Salon. In 1877, he exhibited his celebrated bronze Neapolitan Fisherboy (Pescatore Napoletano). This sculpture, a life-size depiction of a youth emerging from the water, is a masterpiece of naturalism and technical skill. The boy's lithe form, the glistening texture of his skin, and his absorbed expression are rendered with breathtaking verisimilitude. The work was a triumph, earning him widespread acclaim and comparisons to the great masters of the Renaissance, as well as to contemporary French sculptors like Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux, whose own dynamic naturalism had revitalized French sculpture.

The Universal Exposition of 1878 in Paris further cemented Gemito's international standing. He exhibited several works, including a striking portrait bust of the renowned Italian painter Giuseppe Verdi, which captured the composer's intense gaze and formidable presence. He also showed a portrait of the celebrated French painter Ernest Meissonier, a titan of the academic art world, which demonstrated Gemito's ability to capture the likeness and character of prominent figures with the same acuity he applied to his Neapolitan street types. These successes brought him commissions and the admiration of critics and fellow artists. During his time in Paris, he would have been aware of the rising prominence of Auguste Rodin, whose expressive and often tormented figures were beginning to challenge sculptural conventions, though Gemito's path remained more closely aligned with a highly refined realism rooted in classical observation.

Gemito's technical virtuosity was a key component of his success. He was a master of bronze casting, particularly the lost-wax method (cire perdue), a complex ancient technique that he helped to revive and popularize. This method allowed for intricate detail and a unique surface quality, which Gemito exploited to full effect in his works. He also excelled in terracotta, a medium that allowed for greater spontaneity and immediacy, and his drawings, often executed in charcoal or graphite, possess a remarkable sensitivity and power.

The Shadow of Illness and Years of Seclusion

Despite his international triumphs, Gemito's life was not without its shadows. He was a man of intense emotions and a volatile temperament. The pressures of his career, coupled with his inherent sensitivity, began to take a toll. In 1880, he returned to Naples, where he married Anna Cutolo, his model for many works, known as "Nannina." He received a prestigious commission to create a marble statue of Emperor Charles V for the facade of the Royal Palace of Naples.

However, the meticulous and demanding nature of carving marble, a medium with which he was less familiar and perhaps less temperamentally suited than the more malleable clay or wax, proved immensely challenging. Coupled with other personal and professional pressures, this period culminated in a severe mental breakdown around 1887. This crisis marked a tragic turning point in his career.

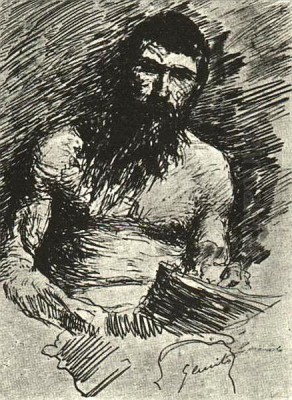

For nearly two decades, from 1887 until around 1909, Gemito lived in almost complete seclusion. He withdrew from public life and largely abandoned sculpture. This long period of inactivity and mental anguish was a profound loss for the art world. During these years, he focused primarily on drawing, producing numerous sketches and studies, often revisiting themes from his earlier career or exploring classical motifs with a new, almost obsessive intensity. His drawings from this period often possess a haunting, introspective quality.

The exact nature of his illness remains a subject of speculation, but its impact on his creative output was undeniable. The "mad artist" persona, already hinted at by his passionate nature, became more pronounced in public perception, though the reality was likely a complex interplay of psychological vulnerability and external pressures.

A Resurgence of Creativity: The Later Years

Around 1909, Vincenzo Gemito slowly began to re-emerge from his self-imposed isolation and returned to sculpture. This later phase of his career was characterized by a renewed focus on classical themes and an even greater refinement of his bronze casting techniques. He seemed to find solace and inspiration in the idealized forms of Greek and Roman art, which had captivated him in his youth.

Works from this period often depict mythological figures, philosophers, and idealized heads, executed with an exquisite attention to detail and a profound understanding of classical aesthetics. His Medusa (1911), for example, is a powerful reinterpretation of the ancient Gorgon myth, imbued with both classical grandeur and a distinctly modern psychological intensity. He also created a series of "philosopher" heads, such as the Head of a Bearded Old Man, which, while inspired by ancient prototypes, convey a deep sense of wisdom, weariness, and inner life.

During this later period, Gemito also dedicated himself to working with precious metals, creating intricate silverwork and gold pieces, often inspired by archaeological finds from Pompeii and Herculaneum. These works demonstrate his versatility and his unwavering commitment to craftsmanship. He continued to draw inspiration from the world around him, but his gaze was increasingly turned towards the timeless ideals of beauty and form embodied in classical art.

His return to sculpture was met with renewed interest, and he continued to work, albeit at a slower pace, until his death in Naples on March 1, 1929. He left behind a legacy as one of Italy's most original and gifted sculptors, an artist who bridged the gap between the raw realism of his contemporary world and the enduring power of classical tradition.

Artistic Style, Techniques, and Thematic Concerns

Vincenzo Gemito's artistic style is a unique synthesis of unflinching realism and profound classicism. His early works, depicting the street life of Naples, are masterpieces of Verismo. He did not romanticize poverty or idealize his subjects in a sentimental way; rather, he portrayed them with an honest and empathetic gaze, capturing their individuality, their resilience, and their inherent dignity. The textures of skin, hair, and ragged clothing are rendered with astonishing fidelity, yet these details never overwhelm the emotional core of the work.

His deep admiration for ancient Greek and Roman sculpture provided a crucial counterpoint to this realism. He absorbed the lessons of classical art – its understanding of anatomy, its balance of form, its idealized beauty – and integrated them into his own work. This is evident not only in his later, more overtly classical pieces but also in the underlying structure and grace of his earlier, realistic figures. He sought to capture what he called the "vero antico" – the "true antique" – a living classicism that was not merely imitative but deeply felt and reinterpreted.

Gemito was a master of various media. His terracotta sketches possess an immediacy and freshness that reveal his creative process. His drawings, whether quick studies or highly finished works, are characterized by their strong lines, subtle modeling, and profound psychological insight. However, it is in bronze that his genius found its fullest expression. He was a pioneer in the revival of the lost-wax casting technique, which allowed him to achieve intricate details and varied surface textures, from the smooth skin of a youth to the rough-hewn features of an old man. His bronzes often have a rich, dark patina that enhances their sculptural form and emotional impact.

Thematically, Gemito's work revolves around the human figure. He was fascinated by the human condition in all its manifestations – the innocence and mischief of childhood, the vitality of youth, the wisdom and weariness of old age. His depictions of Neapolitan street children, such as The Fisherboy or The Water Seller, are not merely genre pieces; they are profound studies of character and humanity. Even in his portraits of famous individuals like Verdi or Meissonier, he sought to penetrate beyond the external likeness to reveal the inner essence of his subject. His later classical works, while drawing on mythological or historical themes, are similarly imbued with a deep psychological understanding.

Contemporaries and Influence

Vincenzo Gemito did not work in a vacuum. He was part of a vibrant artistic scene in Naples and later in Paris. His close association with Antonio Mancini and Francesco Paolo Michetti has already been noted. These artists, along with others like Giuseppe De Nittis (another Italian who found success in Paris), were key figures in the Italian Verismo movement and contributed to a broader European trend towards realism in the late 19th century.

In Paris, Gemito's work was exhibited alongside that of leading French artists. While his style differed from the more academic approach of sculptors like Jean-Léon Gérôme (who also practiced sculpture alongside his famous paintings) or the burgeoning impressionistic tendencies in sculpture seen later in artists like Medardo Rosso, Gemito's powerful realism and technical brilliance earned him respect. His work was often compared to that of Auguste Rodin, his contemporary, though Rodin's path led towards a more fragmented and emotionally turbulent expressionism, while Gemito remained more anchored in observation and classical form.

Gemito's teachers, Emanuele Caggiano and Stanislao Lista, provided him with foundational training, but his primary influences were the street life of Naples and the masterpieces of classical antiquity. He, in turn, influenced a subsequent generation of Italian sculptors, particularly in Naples, who admired his technical skill and his ability to imbue realistic subjects with profound emotional depth. While he is not known to have had formal students in the traditional sense, his example and his powerful body of work served as an inspiration. His revival of the lost-wax casting technique also had a lasting impact on the practice of bronze sculpture.

The Spanish painter Mariano Fortuny, a friend of Michetti and a dazzling technician himself, also moved in similar artistic circles in Paris and Rome, and his vibrant depictions of everyday life, though in painting, shared some of the same spirit of capturing contemporary reality that animated Gemito and his Italian colleagues.

Legacy and Art Historical Reassessment

For a period, particularly during his long years of seclusion and in the decades immediately following his death, Vincenzo Gemito's reputation somewhat faded, overshadowed by the rise of modernism. However, in recent decades, there has been a significant reassessment of his work and his place in art history.

Major retrospective exhibitions, such as those held at the Petit Palais in Paris and the Museo di Capodimonte in Naples, have brought his art to a new generation of viewers and scholars. These exhibitions have highlighted the extraordinary quality and originality of his work, reaffirming his status as one of the most important sculptors of his time. His sculptures are now prized possessions in major museum collections around the world, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Musée d'Orsay in Paris, and, of course, numerous Italian museums.

Art historians now recognize Gemito not merely as a regional Neapolitan artist but as a figure of international significance. His unique fusion of realism and classicism, his technical mastery, and his profound empathy for his subjects distinguish him from his contemporaries. He is seen as an artist who, while deeply rooted in the traditions of his native land and the legacy of antiquity, forged a distinctly personal and modern vision.

His life story, with its dramatic trajectory from poverty to fame and its tragic interruption by mental illness, adds another layer of complexity to his artistic persona. He embodies the archetype of the passionate, tormented genius, yet his art, even at its most intense, is always grounded in a deep understanding of form and a profound respect for the human spirit.

Vincenzo Gemito's legacy endures in his powerful and moving sculptures and drawings. They offer a timeless testament to the beauty and resilience of ordinary people, the enduring power of classical ideals, and the singular vision of an artist who truly sculpted the soul of Naples. His work continues to captivate and inspire, securing his place as a master of 19th and early 20th-century sculpture.