Introduction: A Pivotal Figure in Dutch Art

Hendrick Goltzius (1558–1617) stands as one of the most significant and versatile artists of the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries in the Netherlands. Born in Bracht, a village then in the Duchy of Jülich (near Venlo, now Germany, close to the Dutch border), he became a naturalized citizen of the Dutch Republic and a central figure in the transition from Northern Mannerism to the early Baroque, often referred to as the Dutch Golden Age. Primarily celebrated as a printmaker of astonishing technical skill, Goltzius was also a gifted draftsman and, later in his career, a painter. His work is characterized by its virtuosity, imaginative power, and a fascinating evolution in style, reflecting both native traditions and the profound impact of Italian art. He was a master technician, an influential teacher, and a key figure in the vibrant artistic milieu of Haarlem.

Early Life, Training, and the Defining Injury

Goltzius hailed from a family with artistic roots; his father, Jan Goltz II, was a glass painter, and other relatives were also involved in the arts. This environment likely fostered his early inclination towards visual creation. A pivotal and often recounted event from his childhood was a severe burn to his right hand, sustained in a fire when he was just a year old. The tendons were damaged, leaving his hand partially crippled. Paradoxically, this injury is said to have forced him to develop extraordinary control over his drawing and engraving tools, gripping the burin in a unique way between his palm and fingers. This physical limitation became, in a sense, a source of his unparalleled manual dexterity in printmaking.

His formal training began under his father, learning the basics of drawing and design relevant to glass painting. However, his true apprenticeship in the art that would define his career began around 1575 when he started studying engraving with Dirck Volckertsz. Coornhert. Coornhert was not only an engraver but also a prominent humanist writer, theologian, and politician. This association likely exposed the young Goltzius to intellectual currents beyond mere craft. In 1577, Goltzius followed Coornhert to Haarlem, a city rapidly becoming a major artistic center in the Northern Netherlands. Haarlem would remain Goltzius's base for the rest of his life.

Establishing a Reputation: The Haarlem Printmaker

In Haarlem, Goltzius quickly distinguished himself. Initially, he worked producing engravings for various publishers, including Philip Galle in Antwerp, one of the major print publishing houses of the era. His early works, such as designs for a Lucretia series, already showcased his burgeoning talent and technical proficiency. By 1582, Goltzius took a significant step by establishing his own print publishing business in Haarlem. This move gave him greater artistic and financial independence, allowing him to produce and disseminate his own designs as well as those of other artists.

His workshop became highly successful, attracting talented pupils and assistants, and producing prints that were sought after throughout Europe. Goltzius's business acumen, combined with his artistic genius, made him one of the most influential figures in the Northern European print market. His prints covered a wide range of subjects, including biblical scenes, mythology, allegory, portraiture, and genre scenes, catering to the diverse tastes of the burgeoning collector market.

The Influence of Mannerism and Spranger

During the 1580s, Goltzius's style fully embraced the tenets of international Mannerism. This was significantly spurred by his association with the Flemish artist and writer Karel van Mander, who arrived in Haarlem in 1583. Van Mander, who would later write the influential Schilder-Boeck (Book of Painters), introduced Goltzius to the sophisticated and highly artificial style of Bartholomeus Spranger. Spranger, a Flemish painter working for Emperor Rudolf II at the imperial court in Prague, epitomized the late Mannerist aesthetic with his elongated figures, complex twisting poses (figura serpentinata), erotic undertones, and emphasis on artistic invention (inventio).

Goltzius became the primary engraver responsible for translating Spranger's designs into prints, most famously the series depicting the Marriage of Cupid and Psyche. These engravings, with their dazzling technical display and stylish figures, were instrumental in disseminating the Prague court style throughout Northern Europe and cemented Goltzius's reputation as a virtuoso. His own compositions from this period similarly feature muscular, often exaggerated anatomies, intricate compositions, and a dynamic, sometimes theatrical, energy. He pushed the boundaries of the engraving medium to capture the complex forms and dramatic lighting characteristic of Mannerism.

Unrivaled Technical Mastery: The Swelling Line and Dot System

Goltzius's fame rested significantly on his revolutionary approach to engraving technique. He is particularly renowned for perfecting the "swelling line." Using the burin, the primary tool for engraving, with unparalleled control, he could vary the width and depth of a single incised line, making it swell from a hair-thin mark to a broad, dark stroke and back again within a continuous cut. This allowed him to create remarkable effects of volume, texture, and light, suggesting the plasticity of form in a way previously unseen in engraving. His lines seem to curve around forms, defining muscles, drapery, and space with incredible fluidity and three-dimensionality.

Furthermore, Goltzius developed sophisticated systems of cross-hatching and employed a "dot and lozenge" technique. This involved creating tonal gradations through networks of dots and small diamond shapes laid within or between the hatched lines, allowing for subtle transitions in shading and a richer overall tonal range. His technical brilliance was such that he could convincingly imitate the styles of earlier masters. His famous Meisterstiche (Master Engravings) series of 1593-94 included prints executed in the distinct manners of Albrecht Dürer, Lucas van Leyden, and Italian masters like Raphael and Parmigianino, a feat that astonished his contemporaries and demonstrated his absolute command of the medium.

Masterpieces in Print: Defining Works

Goltzius produced a large body of graphic work, estimated at over 300 prints. Several stand out as defining masterpieces of his career and of late Renaissance/early Baroque printmaking.

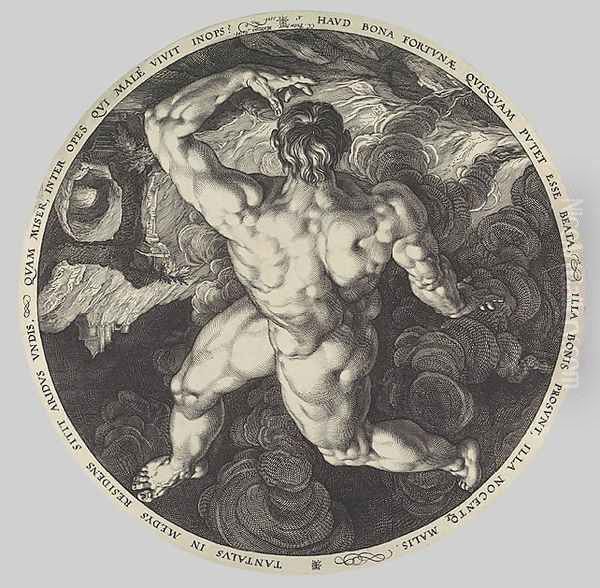

The Four Disgracers (c. 1588): This series depicts mythological figures (Icarus, Phaeton, Tantalus, Ixion) punished for their hubris by falling dramatically through the sky. Engraved on large plates, these prints are tour-de-forces of Mannerist composition and anatomical invention. The muscular figures, seen from extreme perspectives (sotto in sù), showcase Goltzius's virtuosity in rendering complex poses and foreshortening, pushing the boundaries of representation.

Hercules and Cacus (1588): While primarily an engraver, Goltzius also produced woodcuts. This large chiaroscuro woodcut, printed from three blocks (line block and two tone blocks), depicts the muscular hero Hercules defeating the giant Cacus. It is often cited as the pinnacle of Dutch chiaroscuro woodcut production, demonstrating Goltzius's ability to achieve painterly effects of light and volume even in this different relief printing technique. Its monumental scale and dramatic power are remarkable.

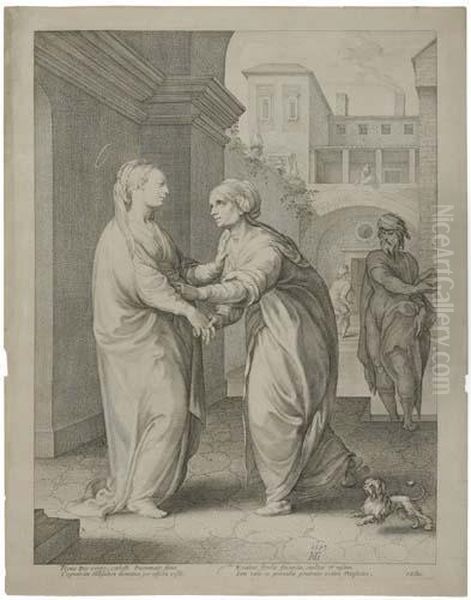

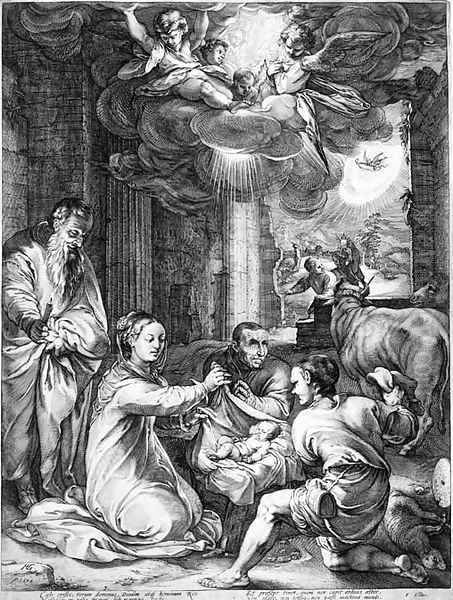

The Life of the Virgin (Meisterstiche series, 1593-94): This series of six engravings, mimicking the styles of earlier masters, includes iconic images like The Annunciation, The Visitation, and The Adoration of the Shepherds. The Circumcision, often considered the highlight, is executed in the style of Dürer with such fidelity that it reportedly fooled experts initially. The series as a whole is a testament to Goltzius's technical versatility and his deep engagement with the history of printmaking.

The Holy Family with the Infant St. John (1593): This engraving, created after his return from Italy, shows a move towards a more classical harmony and tenderness, although the technical brilliance remains. It reflects the influence of Italian Renaissance masters like Raphael, balancing virtuosity with a calmer, more idealized representation.

The Transformative Journey to Italy

In 1590, at the height of his fame as a printmaker, Goltzius embarked on a journey to Italy, traveling through Germany. He visited major artistic centers, including Venice, Bologna, Florence, and, most importantly, Rome, where he stayed for several months before returning to Haarlem in late 1591. This trip was a turning point in his artistic development. He diligently studied antique sculpture, particularly the powerful forms of Roman works like the Farnese Hercules (which he famously drew from multiple viewpoints) and the Belvedere Torso.

He also immersed himself in the works of the Italian High Renaissance masters, especially Michelangelo and Raphael, whose grandeur, classical balance, and idealized naturalism deeply impressed him. He encountered the works of contemporary Italian artists as well, potentially including early works by Caravaggio, though the High Renaissance seems to have had a more immediate impact on his stylistic shift. An anecdote recounted by Karel van Mander tells of Goltzius traveling incognito in Rome, sometimes disguising himself to avoid the constant attention his fame attracted, allowing him to study art undisturbed.

Stylistic Evolution: Towards Classicism

The Italian journey profoundly affected Goltzius's artistic outlook. Upon his return to Haarlem, his work began to show a marked departure from the exaggerated Mannerism of the 1580s. While his technical brilliance never waned, his figures became less contorted and more classically proportioned. Compositions grew calmer and more balanced, and there was a greater emphasis on clarity, grace, and a more naturalistic rendering of form and emotion.

This shift is evident in prints made after his return, such as the aforementioned Holy Family or portraits like the dignified engraving of his former teacher, Dirck Volckertsz. Coornhert (1591-92). He absorbed the lessons of Italian classicism, integrating them into his Northern European sensibility. This move towards a more restrained and idealized style mirrored broader trends in European art around 1600, moving away from Mannerist artifice towards the emerging Baroque classicism.

Goltzius the Draftsman: Pen Works and Portraits

Goltzius was a prolific and exceptionally skilled draftsman throughout his career. His drawings range from quick sketches and compositional studies to highly finished works intended as independent pieces of art. He worked in various media, including pen and ink, chalk (black, red, and white), and colored chalks. His drawings often display the same energy and technical flair as his prints.

He produced remarkable portrait drawings, capturing the likeness and character of his sitters with great acuity. A fine example is the sensitive chalk drawing Portrait of Gillis van Breen (c. 1588), an engraver who worked in Goltzius's circle. His colored chalk portraits were particularly admired by contemporaries like Van Mander for their lifelike quality and technical finesse.

Later in his career, Goltzius created a unique type of artwork known as "pen works" (penwerken). These were large, highly detailed drawings executed with pen and ink on prepared canvas or parchment, often imitating the appearance of engravings. Works like Sine Cerere et Baccho Friget Venus (Without Ceres and Bacchus, Venus Freezes, c. 1599-1602) exemplify this technique. They allowed him to work on a larger scale than typical drawings, combining the linear precision of engraving with a painterly sensibility, showcasing his virtuosity in yet another format.

The Late Career: Goltzius as Painter

Around 1600, Goltzius largely abandoned engraving, the medium that had brought him international fame, and turned his focus almost exclusively to painting. Although he produced fewer paintings than prints, these works are significant contributions to the Dutch Golden Age. His decision might have been prompted by a desire to emulate the Italian masters he admired, for whom painting was the highest form of art, or perhaps by the physical demands of engraving becoming too strenuous.

His paintings primarily depict mythological and biblical subjects, often featuring large-scale nude or semi-nude figures, as well as portraits. Works like Lot and His Daughters (1616) or Vertumnus and Pomona (1613) demonstrate his assimilation of Italianate classicism, characterized by smooth modeling, rich colors, and balanced compositions. Mythological scenes like Cadmus Slaying the Dragon allowed him to explore dynamic compositions and dramatic narratives, though generally rendered with more restraint than his earlier Mannerist prints. While sometimes criticized for a certain coolness or hardness compared to his graphic work, his paintings are technically accomplished and hold an important place in the development of Dutch history painting.

Collaborations, Connections, and the Haarlem 'Academy'

Goltzius was a central figure in the artistic life of Haarlem. His workshop was a hub of activity, training important engravers like his stepson Jacob Matham and Jan Saenredam (father of the painter Pieter Saenredam). He maintained connections with publishers like Philip Galle and artists across the Netherlands and beyond.

His relationship with Karel van Mander and the Haarlem painter Cornelis Cornelisz. van Haarlem was particularly significant. Together, these three are traditionally credited with founding an informal 'academy' in Haarlem around the mid-1580s. This was likely not a formal institution in the modern sense but rather a collaborative arrangement for drawing from life models, studying anatomy, and discussing art theory, reflecting the growing intellectualization of art practice. This initiative played a role in promoting a more academic approach to art in Haarlem, emphasizing anatomical accuracy and classical principles. Goltzius's collaboration with Cornelis van Haarlem is also seen in shared thematic interests, particularly in depicting muscular nudes in mythological or biblical contexts, although a degree of artistic rivalry likely existed alongside their collegiality.

His fame brought him into contact with other major figures. The renowned Flemish master Peter Paul Rubens visited Goltzius in Haarlem in 1612. While the specifics of their exchange are not fully documented, it is known that Rubens greatly admired Goltzius's prints and later established his own highly organized printmaking workshop, possibly drawing some inspiration from Goltzius's successful model. Goltzius's engagement with the works of past masters like Dürer and Lucas van Leyden, through both emulation and reproduction, also highlights his deep connection to the artistic tradition.

Legacy and Enduring Influence

Hendrick Goltzius died in Haarlem on January 1, 1617. He left behind a legacy as one of the most technically brilliant printmakers in the history of Western art and a key transitional figure in Dutch art. His early Mannerist works represent the pinnacle of that style in the Northern Netherlands, while his later classicizing phase paved the way for the Dutch Golden Age.

His influence was immediate and widespread. His prints circulated throughout Europe, admired and collected by connoisseurs and artists alike, including Emperor Rudolf II in Prague. His technical innovations, particularly the swelling line, profoundly impacted subsequent generations of engravers. His students, Jacob Matham and Jan Saenredam, and others like Jan Muller and Jacques de Gheyn II, continued to work in his virtuosic style. His impact can also be seen in the development of reproductive engraving, where his workshop set high standards.

While his reputation experienced fluctuations, particularly in the later seventeenth and eighteenth centuries when Mannerism fell out of favor, his work has been consistently esteemed by print specialists and collectors. Modern scholarship recognizes him as a pivotal figure whose career encapsulates the dynamic artistic exchanges and stylistic shifts occurring in Europe around 1600. His works are held in major museums worldwide, testament to his enduring importance as a master draftsman, printmaker, and painter who pushed the boundaries of his media and left an indelible mark on the art of the Netherlands.

Conclusion: A Master of Transformation

Hendrick Goltzius remains a towering figure in Netherlandish art. His journey from a German-born craftsman's son to the leading printmaker of Northern Europe, and his subsequent transformation into a classicizing painter, reflects both personal ambition and the broader artistic currents of his time. His unparalleled technical skill, particularly in engraving, allowed him to create images of extraordinary power and sophistication. Whether depicting Mannerist extravagance or classical grace, his work is united by a relentless pursuit of virtuosity and a deep engagement with the art of the past and present. As an artist, innovator, and entrepreneur, Goltzius played a crucial role in shaping the visual culture of the Dutch Golden Age and securing a prominent place for Dutch art on the international stage.