Hendrick Terbrugghen stands as one of the most significant and individualistic figures among the Dutch painters who fell under the spell of Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio. Active primarily in Utrecht during the early decades of the 17th century, Terbrugghen was a pioneer in introducing Caravaggesque naturalism and dramatic lighting to the Northern Netherlands. His work, characterized by a unique sensitivity to color, light, and human emotion, formed a crucial bridge between Italian Baroque innovations and the burgeoning Dutch Golden Age of painting. Though his career was relatively short, his impact was profound, influencing a generation of artists and leaving behind a body of work that continues to fascinate and move viewers.

Early Life and Formative Years in Italy

Hendrick Jansz. Terbrugghen (or Ter Brugghen) was likely born in The Hague or possibly Deventer around 1588. His father, Jan Egbertsz ter Brugghen, was from a noble Overijssel family, and had served in various official capacities. The family moved to Utrecht in the early 1590s, a city that, despite the rise of Protestantism, retained strong Catholic traditions and artistic connections with Italy. It was in Utrecht that the young Hendrick embarked on his artistic training, becoming a pupil of Abraham Bloemaert. Bloemaert was a versatile and influential Mannerist painter and a respected teacher, whose workshop trained many prominent artists. Under Bloemaert, Terbrugghen would have received a solid grounding in drawing, composition, and the prevailing artistic conventions of the late 16th century.

Around 1604, or perhaps a little later, Terbrugghen, like many ambitious Northern European artists of his time, traveled to Italy to complete his artistic education. Rome, the vibrant center of the art world, was his primary destination. He remained in Italy for approximately a decade, until 1614. This period was absolutely crucial for his development. It was in Rome that he encountered firsthand the revolutionary art of Caravaggio, who had died in 1610 but whose powerful naturalism and dramatic use of chiaroscuro (the contrast of light and dark) were transforming European painting.

Terbrugghen is believed to have met Peter Paul Rubens in Rome, and according to Terbrugghen's son Richard, Rubens praised Terbrugghen as a significant painter. While in Italy, he would also have been exposed to the work of Caravaggio's immediate followers, known as the Caravaggisti. Artists such as Orazio Gentileschi, Carlo Saraceni, Bartolomeo Manfredi, and the Spaniard Jusepe de Ribera (who was active in Naples but whose influence was felt in Rome) were all developing their own interpretations of Caravaggio's style. Terbrugghen absorbed these influences, particularly the focus on depicting figures with a heightened sense of realism, often drawn from everyday life, and the use of tenebrism to create dramatic, emotionally charged scenes.

Return to Utrecht and the Rise of a Distinctive Style

Terbrugghen returned to Utrecht in late 1614 or early 1615. In 1616, he was registered as a master in the Utrecht Guild of Saint Luke, the city's painter's guild, and he married Jacoba Verbeeck, his elder brother Jan's stepdaughter, in the same year. Utrecht was becoming a significant center for a new kind of art, largely due to artists like Terbrugghen who brought back the Caravaggesque style from Italy. He, along with Gerard van Honthorst and Dirck van Baburen, who also spent time in Italy, became the leading figures of the Utrecht Caravaggisti.

Upon his return, Terbrugghen began to produce a series of paintings that clearly demonstrated his assimilation of Italian Baroque principles, yet also revealed his emerging individuality. His early Utrecht works, from around 1616 to 1620, show a strong adherence to Caravaggesque models, often featuring half-length figures in dramatic lighting, engaged in religious or genre scenes. However, even in these early pieces, a personal note can be discerned. Unlike some of the more theatrical or robust interpretations of Caravaggism, Terbrugghen's work often possessed a quieter, more introspective quality.

His palette, while initially dark and reliant on strong contrasts, gradually began to incorporate lighter, cooler tones. He developed a distinctive way of rendering flesh, often with a slightly pale, almost pearlescent quality, and he showed a keen interest in the textures of fabrics and other materials. His figures, while realistically observed, often have a gentle, melancholic air, distinguishing them from the more boisterous characters found in the works of some of his contemporaries.

Key Themes and Representative Works

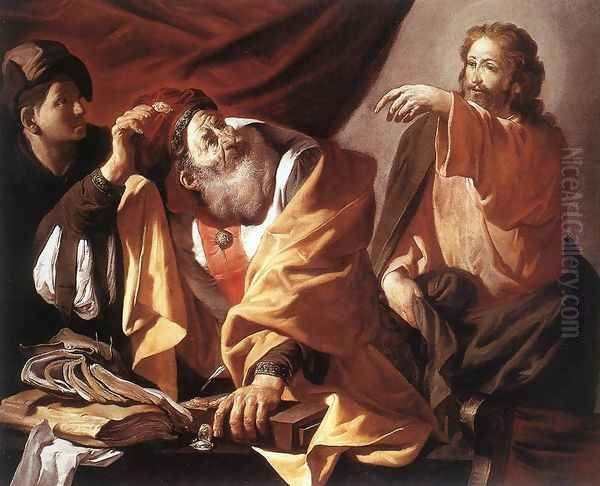

Terbrugghen's oeuvre encompasses a range of subjects, including religious scenes, mythological subjects, and genre paintings, particularly depictions of musicians and drinkers. His religious paintings are notable for their sincere piety and human empathy. Works like The Calling of St. Matthew (c. 1621, Centraal Museum, Utrecht) directly engage with Caravaggio's famous version of the same subject but translate it into Terbrugghen's more lyrical and subtly colored idiom. The figures are expressive, and the play of light across their faces and garments is masterfully handled, creating a sense of spiritual significance within an everyday setting.

Another powerful religious work is The Incredulity of St. Thomas (c. 1621-23, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam). Here, the physical act of Thomas touching Christ's wound is depicted with a stark realism that underscores the painting's theological message. The concentrated light on Christ's torso and the apostles' faces heightens the drama and intimacy of the moment. Terbrugghen’s ability to convey deep emotion through subtle gesture and expression is particularly evident in such works.

His Crucifixion with the Virgin and St. John (c. 1625, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York) is a profoundly moving depiction of the event. The figures are imbued with a quiet sorrow, and the cool, almost silvery light that bathes the scene contributes to its somber and ethereal atmosphere. This work showcases Terbrugghen's mature style, with its sophisticated color harmonies and refined emotional tenor. It deviates from the more overt drama of many Italian Baroque crucifixions, opting instead for a more contemplative and Northern European sensibility.

Terbrugghen also excelled in genre scenes, particularly his depictions of single figures, often musicians. The Flute Player (1621, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Kassel) and Bagpipe Player (1624, Wallraf-Richartz Museum, Cologne) are iconic examples. These paintings, often featuring figures in fanciful, theatrical costumes, capture a sense of immediacy and life. The musicians are not idealized but are portrayed with a robust naturalism, their enjoyment of their music palpable. These works were highly popular and contributed to a broader trend of depicting musicians and revelers in Dutch art, a theme also explored by artists like Frans Hals in Haarlem.

The Concert (c. 1626, National Gallery, London) is a more complex genre scene, showing a group of musicians and singers. The interplay of light and shadow, the varied expressions of the figures, and the rich rendering of their costumes and instruments demonstrate Terbrugghen's skill in creating lively and engaging compositions. Such scenes often carried moralizing undertones, alluding to the transience of pleasure or the senses, but they were also appreciated for their sheer visual appeal and celebration of everyday life.

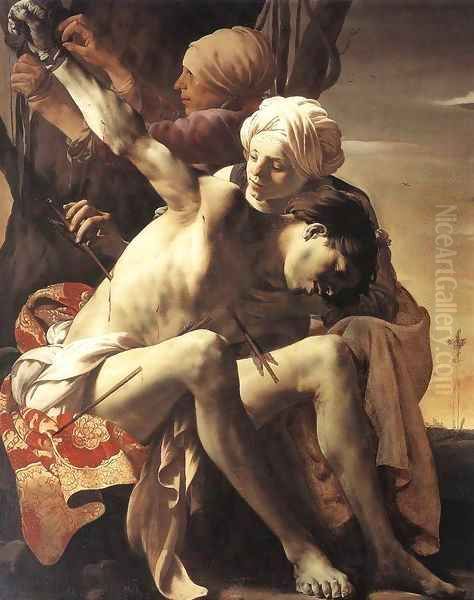

A particularly poignant work is St. Sebastian Tended by Irene (c. 1625, Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin College). This subject, popular in Caravaggesque circles, allowed artists to explore themes of suffering, compassion, and the beauty of the human form. Terbrugghen's version is notable for its tender mood and the delicate play of light on Sebastian's pale skin and Irene's concerned face. The cool blues, grays, and ochres create a harmonious and melancholic atmosphere, typical of his mature style.

Later works, such as Jacob Reproaching Laban (1627, National Gallery, London) and King David Harping, Surrounded by Angels (c. 1628, National Museum, Warsaw), show a further lightening of his palette and a softening of his forms. The dramatic chiaroscuro of his earlier period gives way to a more diffused, atmospheric light, and his colors become even more nuanced and subtle. These works demonstrate his continued artistic evolution and his movement towards a style that, while still rooted in Caravaggism, was increasingly personal and refined.

Artistic Style: Light, Color, and Emotion

Terbrugghen's artistic style is a fascinating blend of Italian Baroque drama and Northern European sensitivity. His most defining characteristic is his unique handling of light and color. While he adopted Caravaggio's tenebrism, he often tempered it with a cooler, more silvery light, avoiding the harsh, almost brutal contrasts found in some of Caravaggio's works or those of his more direct followers like the young Jusepe de Ribera. Terbrugghen's light often seems to emanate from within the figures or to gently caress their forms, creating a sense of volume and texture without sacrificing subtlety.

His color palette is distinctive. He frequently employed cool blues, grays, lilacs, and yellows, often in unexpected combinations. This use of color contributes to the often melancholic or pensive mood of his paintings. Even in his more boisterous genre scenes, there is often an underlying sense of introspection. He had a remarkable ability to model forms with color and light, creating a sense of plasticity and presence. The way he rendered fabrics, with their rich folds and subtle sheen, is particularly noteworthy.

In terms of composition, Terbrugghen favored relatively simple, uncluttered arrangements, often focusing on a few large figures placed close to the picture plane. This directness enhances the emotional impact of his scenes, drawing the viewer into an intimate engagement with the figures and their experiences. His figures themselves are often characterized by a certain ruggedness and lack of idealization, in keeping with Caravaggesque principles. However, they also possess a psychological depth and a sense of quiet dignity that is uniquely Terbrugghen's. He avoided the overt theatricality of some of his contemporaries, opting instead for a more restrained and nuanced expression of emotion.

There is sometimes an almost archaic quality to his figures, a slight stiffness or angularity that harks back to earlier Northern traditions, perhaps even to artists like Albrecht Dürer or Lucas van Leyden in their approach to realism. This blend of modern Italianate naturalism with a lingering Northern Gothic sensibility gives his work a unique flavor.

Connections and Influence: The Utrecht School and Beyond

Hendrick Terbrugghen was a central figure in the Utrecht Caravaggisti, alongside Gerard van Honthorst and Dirck van Baburen. While all three artists were deeply influenced by Caravaggio, they each developed distinct personal styles. Honthorst, known as "Gherardo delle Notti" (Gerard of the Night Scenes) in Italy, became famous for his dramatic candlelit scenes, which were often more overtly theatrical and robust than Terbrugghen's work. Baburen, whose career was tragically short (he died in 1624), produced powerful and often earthy interpretations of Caravaggism.

Terbrugghen's style was perhaps the most lyrical and introspective of the three. His influence on his Utrecht contemporaries is evident, and together they created a vibrant artistic center that played a crucial role in disseminating Caravaggesque ideas in the Netherlands. The impact of the Utrecht Caravaggisti extended beyond their immediate circle. Their work helped to pave the way for the great masters of the Dutch Golden Age, such as Rembrandt van Rijn and Frans Hals, who, while not direct followers, absorbed aspects of Caravaggesque naturalism and chiaroscuro into their own revolutionary styles.

There has been much art historical discussion about Terbrugghen's potential influence on Johannes Vermeer. While direct links are difficult to prove, some scholars have noted similarities in their sensitivity to light and color, and in the quiet, introspective mood of their paintings. Vermeer may have seen Terbrugghen's work, possibly through collections in Delft or nearby cities. The subtle gradations of light and the harmonious color schemes found in Terbrugghen's later works resonate with Vermeer's own refined aesthetic.

The renowned Flemish master Peter Paul Rubens is said to have visited Terbrugghen's studio during a trip to the Netherlands in 1627 and reportedly praised him as the only true painter he had encountered there. While this account comes from Terbrugghen's son and might be embellished, it suggests that Terbrugghen's talent was recognized by leading artists of his time. Rubens himself, though developing a very different, more dynamic Baroque style, shared an appreciation for strong modeling and expressive figures, and would have recognized the quality of Terbrugghen's work. This contrasts with the more classical or mannerist styles still prevalent in some parts of the Netherlands.

Anecdotes and Personal Details

Relatively few personal anecdotes about Hendrick Terbrugghen have survived, which is not uncommon for artists of this period unless they were particularly flamboyant or well-documented by biographers like Karel van Mander (whose Schilder-boeck predates Terbrugghen's main career) or Arnold Houbraken (who wrote much later). We know he was from a respectable family, and his marriage and guild membership suggest a conventional professional life.

His son, Richard Terbrugghen, later provided some biographical information, including the account of Rubens's visit and praise. Richard also emphasized his father's piety and good character. The fact that Terbrugghen focused on religious subjects throughout his career, even in a predominantly Protestant city, suggests a sincere personal faith, or at least a deep engagement with spiritual themes. Utrecht, it should be noted, had a significant Catholic minority, which provided patronage for religious art.

The most significant "event" or "story" associated with Terbrugghen, from an art historical perspective, is perhaps his posthumous period of relative obscurity followed by his rediscovery in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. For many years, his work was overshadowed by that of other Dutch masters, and his importance as a pioneer of Caravaggism was not fully appreciated. Scholars like Cornelis Hofstede de Groot, Wilhelm von Bode, and particularly Benedict Nicolson were instrumental in reassessing his oeuvre and establishing his rightful place in art history.

Untimely Death and Lasting Legacy

Hendrick Terbrugghen's promising career was cut short by his untimely death. He died in Utrecht on November 1, 1629, at the relatively young age of 41. The cause of his death is believed to have been the plague, which swept through Utrecht that year. His death was a significant loss for Dutch art, as he was at the height of his artistic powers and continuing to evolve his distinctive style. One can only speculate on how his art might have developed further had he lived longer.

Despite his relatively short career, Terbrugghen left a lasting legacy. He was one of the first and most important artists to introduce the Caravaggesque style to the Netherlands, and his work played a crucial role in the development of Dutch Golden Age painting. His unique blend of Italian Baroque drama and Northern European sensitivity, his sophisticated use of color and light, and his ability to convey profound human emotion distinguish him as one of the most original and appealing artists of his time.

His influence can be seen in the work of other Utrecht artists, and his paintings were collected and admired. However, as artistic tastes changed in the later 17th century, with a move towards more classical and refined styles, the robust naturalism of the Caravaggisti, including Terbrugghen, fell somewhat out of favor. It was not until the late 19th and early 20th centuries that his work was rediscovered and his true significance recognized.

Art Historical Evaluation and Rediscovery

In the centuries following his death, Hendrick Terbrugghen's name and work gradually faded into relative obscurity, overshadowed by the towering figures of Rembrandt, Vermeer, and Hals. While some of his paintings were occasionally misattributed or simply overlooked, his pivotal role in the transmission of Caravaggism to the North was not fully understood.

The revival of interest in Baroque art in the late 19th century, and particularly the scholarly re-evaluation of Caravaggio and his followers in the early 20th century, led to a renewed appreciation for Terbrugghen. Art historians began to identify his works, distinguish his hand from that of his contemporaries, and piece together his artistic development. Benedict Nicolson's monograph on Terbrugghen, published in 1958, was a landmark study that firmly established the artist's importance and provided a comprehensive overview of his oeuvre.

Today, Hendrick Terbrugghen is regarded as a major figure in Dutch art and a key exponent of Caravaggism outside Italy. He is admired for his artistic individuality, his sensitive and nuanced interpretations of religious and genre subjects, and his mastery of light and color. His ability to infuse his paintings with a quiet, melancholic poetry sets him apart from many of his contemporaries. His works are now prized possessions in major museums around the world, and he is recognized as an artist who successfully forged a highly personal style from diverse influences, creating paintings of enduring beauty and emotional power. His legacy lies not only in his direct impact on his contemporaries but also in the way his art prefigured certain qualities of later Dutch masters, contributing to the rich tapestry of 17th-century European painting. He remains a testament to the vibrant cross-cultural artistic exchanges that characterized the Baroque era.