Introduction: An Artist of the Night

Gerrit van Honthorst (1592-1656) stands as a pivotal figure in the rich tapestry of Dutch Golden Age painting. Born in Utrecht, a city that would become synonymous with his name and influence, Honthorst carved a unique niche for himself through his masterful manipulation of light and shadow. His time spent in Italy profoundly shaped his early style, earning him the evocative nickname "Gherardo delle Notte" – Gerard of the Night – for his captivating nocturnal scenes illuminated by artificial light sources. A prolific painter of religious narratives, genre scenes, mythological subjects, and portraits, Honthorst achieved international fame, serving patrons from the Dutch elite to European royalty, leaving an indelible mark on the trajectory of Baroque art in Northern Europe.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Utrecht

Gerrit Hermansz. van Honthorst was born on November 4, 1592, into a Catholic family in Utrecht. His background was connected to the arts; his father, Herman Gerritsz. van Honthorst, was a decorative painter and tapestry weaver, and reportedly one of the founders of the Utrecht Guild of Saint Luke. Some accounts also mention his grandfather's profession as an interior decorator, suggesting an early familial exposure to visual aesthetics and craftsmanship, possibly sparking an interest in the interplay of light within spaces.

Formal artistic training began under the tutelage of Abraham Bloemaert, a leading Utrecht painter and a highly respected teacher. Bloemaert's studio was a significant artistic hub in the city. His own style evolved from late Mannerism towards a more Italianate approach, providing Honthorst with a solid foundation in drawing, composition, and the prevailing artistic trends. Bloemaert's influence likely instilled in the young Honthorst a technical proficiency and an awareness of international styles, preparing him for the next crucial phase of his development.

The Italian Sojourn: Embracing Caravaggism

Around 1610, like many ambitious Northern European artists of his generation, Honthorst embarked on a journey to Italy, the undisputed center of the art world at the time. He settled primarily in Rome, immersing himself in the city's vibrant artistic milieu. This period proved transformative, largely due to his encounter with the revolutionary works of Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, who had died shortly before Honthorst's likely arrival but whose powerful influence still dominated the Roman art scene.

Honthorst was captivated by Caravaggio's dramatic realism, his use of ordinary people as models for sacred figures, and, most significantly, his mastery of chiaroscuro – the intense contrast between light and dark – often referred to as tenebrism when large areas of the canvas are plunged into shadow. Honthorst absorbed these lessons, adopting the use of strong, often single, artificial light sources like candles or lamps to illuminate his subjects, creating scenes filled with heightened drama, intimacy, and psychological intensity.

During his decade-long stay in Italy (roughly until 1620), Honthorst gained considerable recognition. He attracted prestigious patrons, including Cardinal Scipione Borghese, a major art collector and nephew of Pope Paul V, and Vincenzo Giustiniani, a prominent banker and intellectual whose collection included several works by Caravaggio. He also reportedly worked for Cosimo II de' Medici, the Grand Duke of Tuscany, in Florence. It was during this period that he produced many of the works that cemented his reputation as a master of night scenes, such as the dramatic Beheading of Saint John the Baptist (1618) and the poignant Christ Before the High Priest (c. 1617). His popular genre scenes, like The Supper Party (1620), often depicting musicians and revellers gathered around a candlelit table, further solidified his fame and led to the Italians bestowing upon him the nickname "Gherardo delle Notte."

Return to Utrecht: Leading the Caravaggisti

Honthorst returned to his native Utrecht in 1620, his reputation preceding him. He quickly established a large and successful workshop, becoming a leading figure in what is now known as the Utrecht School, or the Utrecht Caravaggisti. This group of artists, including notable figures like Hendrick ter Brugghen and Dirck van Baburen, had also spent time in Italy and were instrumental in introducing and popularizing the Caravaggesque style in the Dutch Republic. Honthorst's return significantly boosted the movement's prominence.

His success was immediate and widespread. In 1622, he married Sophia Coopsman, who came from a similar background (her father was also a merchant). The same year, he joined the Utrecht Guild of Saint Luke, the professional organization for painters, and his stature was such that he was elected its dean (or head) in 1623, a position he would hold several times throughout his career. His studio flourished, attracting numerous pupils and assistants, helping to disseminate his style and techniques. His brother, Willem van Honthorst, was also a painter, often working in a style similar to Gerrit's later period.

Honthorst's Utrecht workshop produced a wide array of works, catering to the diverse demands of the Dutch art market. He continued to paint religious subjects, often for clandestine Catholic churches (schuilkerken) or private patrons, as well as mythological scenes and the popular candlelit genre paintings that had made him famous in Italy. His skill in rendering textures, capturing expressions, and creating compelling compositions ensured a steady stream of commissions.

Artistic Style: The Master of Candlelight

Honthorst's signature style, particularly in the 1620s, is defined by his innovative use of artificial light. Unlike the diffuse daylight often favored by other Dutch masters, Honthorst embraced the dramatic potential of candlelight, lamplight, or hidden light sources. This allowed him to sculpt his figures out of deep shadow, focusing the viewer's attention and heightening the emotional impact of the scene. His figures often emerge into the light, their faces and gestures animated by the warm glow, while backgrounds recede into near-total darkness.

His genre scenes from this period are particularly characteristic. Works like The Concert (c. 1623) or The Merry Fiddler (1623) depict lively gatherings, often featuring musicians, drinkers, and card players enjoying themselves around a table. The single candle, frequently shielded or placed strategically within the composition, becomes the focal point, casting dramatic shadows and highlighting smiling faces, colourful costumes, and gleaming instruments or glasses. These paintings possess a palpable sense of immediacy and conviviality, combined with the underlying drama of the intense lighting.

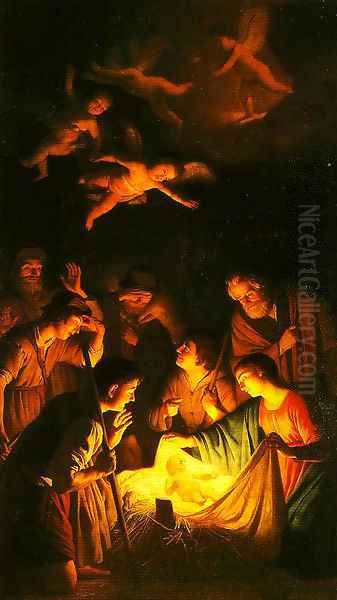

His religious works from this era employ the same techniques to different ends. In The Adoration of the Shepherds (c. 1622), the infant Christ himself seems to be the source of divine light, illuminating the faces of Mary, Joseph, and the adoring shepherds in a scene of tender reverence, set against a dark, humble stable. In Christ Before the High Priest, the stark lighting emphasizes the confrontation and the gravity of the moment. Honthorst skillfully used tenebrism not just for visual effect, but to underscore the narrative and emotional core of his subjects.

Evolution of Style: Brighter Palettes and Courtly Elegance

While Honthorst never entirely abandoned his famed nocturnal scenes, his style underwent a noticeable evolution, particularly from the late 1620s onwards. His palette gradually brightened, the stark contrasts of light and shadow softened, and his compositions often adopted a more classical, sometimes more decorative, elegance. This shift may have been influenced by several factors, including changing tastes in the Dutch market, the influence of Flemish painters like Peter Paul Rubens and Anthony van Dyck (especially their courtly styles), and the demands of his increasingly aristocratic clientele.

This later style is particularly evident in his portraiture and large-scale decorative commissions. He became highly sought after as a portrait painter, renowned for his ability to capture a likeness while imbuing his sitters with an air of dignity and status. His lighting became more even, his brushwork smoother, and his settings often more elaborate than in his earlier, earthier works. He developed a reputation for flattering, yet insightful, depictions of the Dutch elite.

Portraiture and Prestigious Commissions

Honthorst's success extended far beyond Utrecht. He became a favourite painter of the Dutch Stadtholder, Frederick Henry, Prince of Orange, and his wife, Amalia of Solms-Braunfels. He executed numerous portraits of the couple and their children, as well as large decorative schemes for their palaces, including Huis ten Bosch and Honselaarsdijk. A notable example is the double portrait Frederick Henry and Amalia of Solms-Braunfels (1637/1638), which showcases his more refined, courtly style.

His fame reached international shores. In 1628, Honthorst travelled to London at the invitation of King Charles I of England, a renowned art connoisseur. During his six-month stay, he painted portraits of the King, Queen Henrietta Maria, and the Duke of Buckingham, as well as a large allegorical ceiling painting for the Banqueting House at Whitehall, depicting Apollo and Diana. This prestigious commission further enhanced his international standing. He also received commissions from King Christian IV of Denmark and maintained connections with Elizabeth Stuart, the exiled Queen of Bohemia (sister of Charles I), who resided in The Hague. These royal connections cemented his status as one of the most successful and sought-after painters of his time.

Diverse Themes: From Mythology to Merry Companies

Throughout his career, Honthorst demonstrated remarkable versatility in his choice of subject matter. While renowned for his candlelit genre scenes and religious narratives, his oeuvre encompassed a broad range. Mythological subjects, often treated with the same dramatic lighting as his religious works, allowed him to explore classical themes popular during the Baroque period.

His genre paintings, often referred to as 'merry companies', remained popular. These scenes, depicting musicians, drinkers, gamblers, and sometimes figures representing professions like dentistry (e.g., The Tooth Puller), offered lively glimpses into contemporary social life, albeit often with underlying moralizing tones or allegorical meanings related to the senses or transience. Works like The Matchmaker (c. 1625) combine the candlelit intimacy with a narrative of negotiation and perhaps seduction. While the source mentions Winter Games in the City, his typical genre scenes are more often interior gatherings.

Religious painting remained a constant thread. Works like Christ Crowned with Thorns continued to explore biblical narratives with emotional intensity, using his characteristic lighting to focus on the suffering and divinity of Christ. He adeptly blended the sacred and the profane, often using realistic models and settings that made biblical stories feel immediate and relatable to his contemporary audience.

Workshop, Influence, and Contemporaries

Gerrit van Honthorst's workshop in Utrecht was highly productive and influential. He trained a number of pupils, although few achieved his level of fame. His style, particularly his handling of light, left a significant mark on Dutch art. While direct tutelage is debated, scholars suggest his work influenced major figures like Rembrandt van Rijn, especially in Rembrandt's early Leiden period where dramatic chiaroscuro is prominent. The young Jan Lievens, who worked closely with Rembrandt in Leiden, also shows clear affinities with the Utrecht Caravaggisti style, likely absorbing influences from Honthorst and Ter Brugghen.

Within Utrecht, Honthorst and Hendrick ter Brugghen were the leading lights of the Caravaggist movement. Though rivals, their work shared common ground in adapting Italian tenebrism to Northern tastes. Honthorst's influence can also be seen, albeit perhaps more diffusely, in the work of later Dutch genre painters who explored effects of light, even if they moved away from strict tenebrism. The source mentions possible interactions with painters like Pieter de Hooch, known for his tranquil, light-filled interiors, and Gerard Dou, a Leiden 'fijnschilder' (fine painter) known for meticulous detail and often incorporating candlelit scenes, suggesting Honthorst's popularization of night scenes had broad resonance. His impact extended beyond the Netherlands, contributing to the broader European fascination with Caravaggesque effects.

Legacy and Art Historical Significance

Gerrit van Honthorst occupies a crucial position in 17th-century European art. He was the most internationally famous of the Utrecht Caravaggisti and a primary conduit for transmitting Caravaggio's revolutionary style to Northern Europe. His mastery of artificial light created a distinct and influential body of work, earning him his enduring nickname "Gherardo delle Notte."

His ability to adapt his style, moving from intense tenebrism to a brighter, more elegant courtly manner, demonstrates his versatility and business acumen, allowing him to cater to a wide range of patrons, from church officials and private citizens to the highest levels of European royalty. He excelled in multiple genres – religious history, mythology, portraiture, and genre scenes – leaving behind a large and varied oeuvre.

While his fame perhaps waned slightly in the centuries immediately following his death compared to contemporaries like Rembrandt or Vermeer, modern art history recognizes his significant contribution. He is celebrated for his technical skill, his innovative use of light to create mood and drama, and his role in the international exchange of artistic ideas during the Baroque era. His works are held in major museums worldwide and continue to be studied for their artistic merit and historical importance. He died in Utrecht on April 27, 1656, leaving behind a rich legacy as a master painter of the Dutch Golden Age.