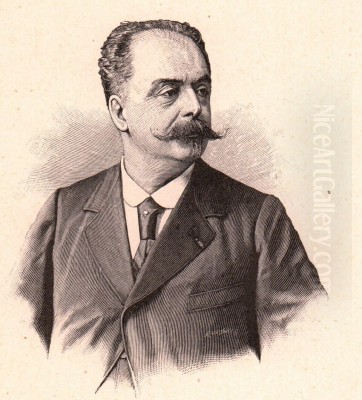

Henri Brispot (1846-1928) stands as a notable, if sometimes overlooked, figure in late 19th and early 20th-century French art. A dedicated painter of Parisian life, genre scenes, and landscapes, Brispot's work offers a fascinating window into the society of his time. Beyond his traditional artistic pursuits, he holds a unique and significant place in the nascent history of cinema as the designer of the world's first film poster. This dual legacy marks him as an artist who not only captured his era on canvas but also contributed to the visual language of a revolutionary new medium.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born in Beauvais, Oise, France, in 1846, Henri Brispot's artistic journey would eventually lead him to the bustling heart of the French art world, Paris. While specific details of his early childhood remain somewhat scarce, it is known that he pursued formal artistic training, a common path for aspiring painters of his generation. His known teachers included Émile Lassalle and a figure referred to as M. Donnat. This tutelage would have grounded him in the academic traditions prevalent at the time, emphasizing draughtsmanship, composition, and a realistic representation of subject matter.

The Paris that Brispot eventually settled in was a city undergoing immense transformation and artistic ferment. The latter half of the 19th century saw the rise of Haussmannian Paris, with its grand boulevards and new urban spaces, providing endless inspiration for artists. It was also a period of diverse artistic movements, from the lingering influence of Academic art championed by figures like Jean-Léon Gérôme and William-Adolphe Bouguereau, to the revolutionary stirrings of Realism led by Gustave Courbet, and the burgeoning Impressionist movement. Brispot would navigate this complex artistic landscape, carving out his own niche.

Artistic Style and Thematic Focus

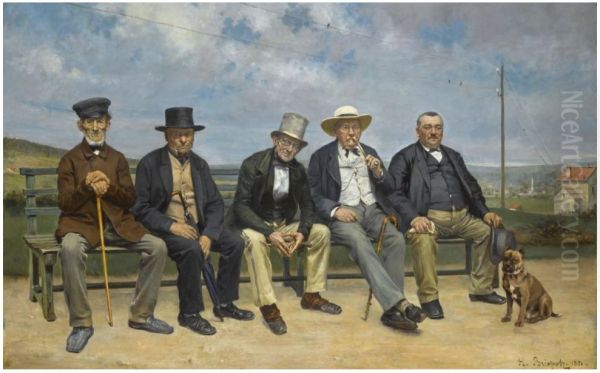

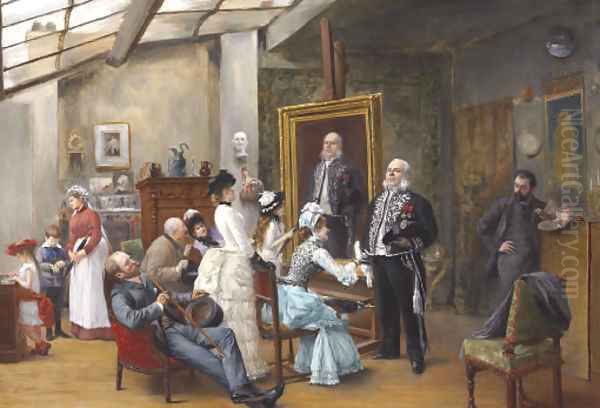

Henri Brispot's artistic style is predominantly characterized by Realism. He possessed a keen eye for detail and a talent for capturing the nuances of human expression and social interaction. His paintings often depict scenes of everyday Parisian life, from quiet moments of contemplation to lively social gatherings. He was adept at portraying figures within their environments, whether it be the interior of a café, a sunlit park, or a domestic setting.

His works demonstrate a careful attention to composition and a skilled use of oil paint, often rendering textures and light with a subtle proficiency. Unlike the Impressionists, such as Claude Monet or Pierre-Auguste Renoir, who were preoccupied with capturing the fleeting effects of light and color through broken brushwork, Brispot maintained a more traditional, smoother finish. His realism was less about social critique, as seen in some works by Honoré Daumier or Jean-François Millet, and more focused on the charming, anecdotal, and picturesque aspects of contemporary life.

Brispot's subjects often included figures from various walks of life, showcasing a broad interest in the social fabric of Paris. He painted elegant ladies in parks, contemplative individuals, and scenes that hinted at narratives, inviting the viewer to imagine the stories behind the depicted moments. His landscapes, too, were rendered with a sensitivity to atmosphere and place, often imbued with a tranquil quality.

Notable Works and Recognition

Throughout his career, Henri Brispot exhibited his works, gaining recognition for his skill. A significant accolade was the silver medal he received at the prestigious Exposition Universelle of 1889 in Paris for his painting titled En province (In the Province). This world's fair, famously marked by the unveiling of the Eiffel Tower, was a major international showcase for arts and industry, and an award there signified considerable contemporary esteem.

Among his known works, several titles give an indication of his thematic range:

Les belles au parc Monceau (The Beauties in Parc Monceau), painted in 1908, is a quintessential example of his Parisian scenes, likely depicting elegant women enjoying leisure time in one of Paris's famed parks. Such scenes were popular, reflecting the bourgeois lifestyle and the city's public spaces as arenas for social display. This work, an oil on canvas measuring 84 x 116.5 cm, was noted as being in the La Fayette gallery in Paris.

Le cuisinier étudiant une recette (The Cook Studying a Recipe) showcases his interest in genre scenes, capturing a moment of everyday domestic activity with a focus on character and setting.

The Chess Players is another example of his genre painting, a theme explored by many artists throughout history, from the Dutch Golden Age painters to contemporaries like Thomas Eakins in America. Such scenes allowed for the depiction of concentration, strategy, and quiet social interaction.

His illustrative work, such as Personnage d'église jouant du serpent (Church Figure Playing the Serpent Instrument) and Chantres au lutrin (Choristers at the Lectern), created in 1876, demonstrates his versatility and ability to work in different formats, likely for publication. The "serpent" is an old bass wind instrument, and such scenes of church musicians were part of a tradition of depicting clerical life and religious observance.

These works, whether grand Salon paintings or smaller genre pieces, consistently reveal Brispot's commitment to a detailed and accessible realism, making his art relatable to a broad audience. His contemporary, Jean Béraud, also specialized in capturing Parisian life with a similar, though perhaps more society-focused, detailed realism, offering an interesting comparison.

The Dawn of Cinema: Brispot and the Lumière Brothers

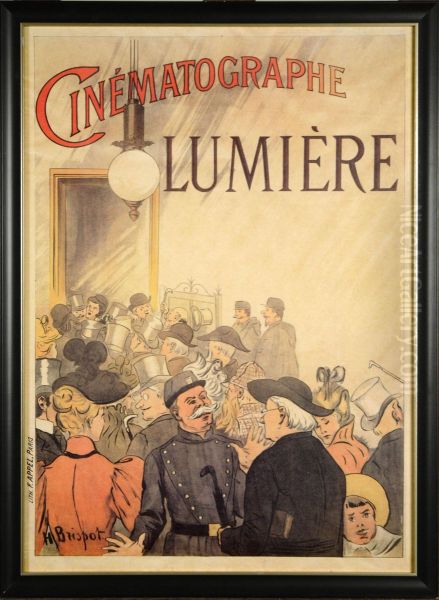

Perhaps Henri Brispot's most enduring claim to fame, and certainly his most unique contribution, lies in his association with the pioneering Lumière Brothers, Auguste and Louis. In the mid-1890s, the Lumières were at the forefront of developing motion picture technology. Their invention, the Cinématographe, a device that could record, develop, and project film, was patented in 1895.

On December 28, 1895, the Lumière Brothers held the first public, commercial screening of their short films at the Salon Indien du Grand Café in Paris. This event is widely considered the birth of cinema as a public entertainment. To promote these revolutionary screenings, the Lumière Brothers commissioned Henri Brispot to design a poster. This commission resulted in what is now recognized as the world's first film poster, titled Cinématographe Lumière.

The poster, created in 1896, vividly depicts a crowd of eager Parisians, men and women from various social strata, jostling to enter a venue to witness the marvel of moving pictures. It captures the excitement and curiosity generated by this new invention. Brispot's design is dynamic, effectively conveying the popular appeal and novelty of the Cinématographe. The imagery is characteristic of his observational style, translated into the graphic medium of the poster. This work is not merely an advertisement; it is a historical document, a visual testament to a pivotal moment in cultural history.

The significance of this poster cannot be overstated. It marked the beginning of a new art form – film poster design – which would evolve dramatically over the following century. Brispot's creation set a precedent, demonstrating the power of visual art to promote and define the emerging medium of cinema. The historical and artistic value of this poster is underscored by its auction prices; one such original poster for the Cinématographe Lumière fetched a remarkable £160,000 at a Sotheby's auction, highlighting its rarity and importance.

This collaboration places Brispot at an extraordinary intersection of traditional art and groundbreaking technology. While artists like Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec were revolutionizing poster art for cabarets and performers with their bold Art Nouveau designs, Brispot was applying his Realist sensibilities to herald the arrival of cinema.

The Artistic Milieu: Paris in the Belle Époque

Henri Brispot's career spanned a significant portion of the Belle Époque (roughly 1871-1914), a period of peace, prosperity, and cultural dynamism in France, particularly in Paris. This era witnessed an explosion of artistic creativity across various movements. While Brispot largely remained within the Realist tradition, he was surrounded by a whirlwind of innovation.

The Impressionists, including Camille Pissarro and Berthe Morisot, had already challenged academic conventions with their focus on en plein air painting and subjective visual experience. Following them, the Post-Impressionists like Vincent van Gogh, Paul Gauguin, Georges Seurat (with his Pointillism), and Paul Cézanne (with his structural approach to form) pushed the boundaries of art even further, exploring emotional expression, symbolism, and new theories of color and composition.

Simultaneously, Symbolism, with artists like Gustave Moreau and Odilon Redon, delved into the world of dreams, myths, and the subconscious. The Art Nouveau movement, characterized by its organic, flowing lines, found expression in painting, decorative arts, and architecture, with Alphonse Mucha becoming famous for his decorative posters.

The official Salon system, though increasingly challenged, still held considerable sway, and artists like Brispot would have regularly submitted works for exhibition. The Salons were grand public spectacles, and success there could significantly boost an artist's career. Brispot's silver medal at the 1889 Exposition Universelle attests to his ability to gain recognition within this established framework.

His focus on Parisian daily life can be compared to that of other contemporaries. For instance, Edgar Degas, while stylistically different, also meticulously observed Parisian life, from ballet dancers to café scenes. The works of artists like Jules Bastien-Lepage, who combined academic technique with a Realist depiction of rural life, also provide context for the kind of artistic environment Brispot inhabited. He was part of a generation that saw art diversifying in unprecedented ways, yet he maintained a consistent vision rooted in careful observation and skilled representation.

Legacy and Enduring Significance

Henri Brispot passed away in 1928. While he may not be as widely known today as some of his revolutionary contemporaries like Monet or Van Gogh, his contributions remain significant. His paintings offer valuable historical and social documents of Parisian life during a transformative period. They capture the atmosphere, fashions, and social customs of the Belle Époque with a charm and sincerity that continues to appeal. His works appear in auctions, indicating a sustained interest among collectors of 19th-century European art.

His role in the history of cinema, however, elevates his legacy beyond that of a competent genre painter. The Cinématographe Lumière poster is a landmark achievement. It connects the world of traditional fine art to the birth of a new global medium. In this single piece, Brispot bridged two distinct yet increasingly interconnected visual cultures. As film rapidly evolved from a novelty into a dominant art form and industry, the visual marketing associated with it, beginning with Brispot's design, became an integral part of its cultural impact.

The fact that Brispot, an established painter recognized by institutions like the Exposition Universelle, was chosen for this task speaks to the Lumière Brothers' desire to lend legitimacy and artistic appeal to their invention. His poster helped to frame cinema not just as a technological marvel but as a respectable and exciting form of public entertainment.

Conclusion: A Painter of His Time and a Herald of the Future

Henri Brispot was an artist deeply rooted in his time and place. As a painter, he skillfully and affectionately chronicled the Paris of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, contributing to the rich tradition of French Realist and genre painting. His canvases preserve moments of everyday life, imbued with a quiet dignity and observational acuity. He was a recognized talent, earning accolades and finding an audience for his depictions of the world around him.

Beyond his paintings, Brispot's design for the first film poster secures him a unique and lasting place in cultural history. This singular act connected him to the very genesis of cinema, making him an unwitting pioneer in the visual promotion of what would become one of the most influential art forms of the 20th century and beyond. Henri Brispot's legacy, therefore, is twofold: that of a dedicated artist capturing the spirit of his era, and that of an important, though perhaps accidental, contributor to the visual iconography of early cinema. His work continues to offer insights into the artistic and social currents of his day, and his famous poster remains a potent symbol of a world on the cusp of a new age of visual experience.