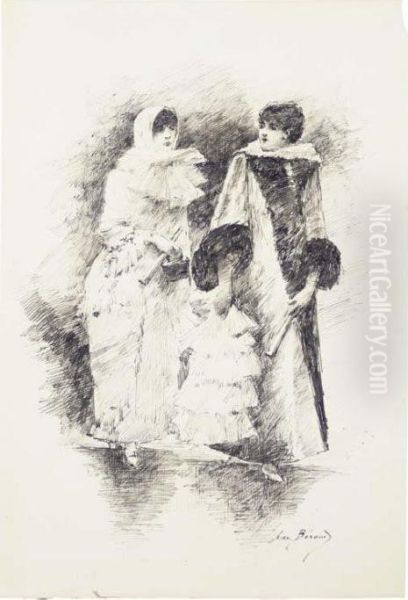

Introduction: A Painter of Parisian Modernity

Jean Béraud stands as one of the most dedicated and insightful visual chroniclers of Parisian life during the vibrant era known as the Belle Époque. Born not in Paris but in St. Petersburg, Russia, on January 12, 1849, he became inextricably linked with the French capital, dedicating his artistic career to capturing its boulevards, cafes, social gatherings, and the myriad characters that populated its streets. His death in Paris on October 4, 1935, marked the end of a long life spent observing and depicting the city's transformation and the nuances of its modern society. Béraud developed a unique style, blending the meticulous detail associated with academic painting with the atmospheric effects and contemporary subject matter favoured by the Impressionists, creating a rich and enduring portrait of his time.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Jean-Georges Béraud's early life was marked by displacement and a shift in professional aspirations. His father was a sculptor, suggesting an early exposure to the arts, but tragically passed away while the family was in St. Petersburg. Following this loss, Béraud's French mother moved the family to Paris. There, he pursued a traditional path, initially studying law. However, the allure of art proved stronger. The experience of the Franco-Prussian War (1870-1871) and his participation in the defence of Paris during the Siege may have also played a role in focusing his attention on contemporary life and the urban environment.

Abandoning his legal studies, Béraud sought formal artistic training. He entered the studio of Léon Bonnat around 1872. Bonnat was a highly respected figure in the Parisian art world, known for his portraits and historical paintings, and grounded in the academic tradition. This training provided Béraud with a strong foundation in draughtsmanship and composition. However, Béraud quickly turned his skilled technique towards subjects that were distinctly modern. He made his official debut in the art world by exhibiting at the prestigious Paris Salon in 1873, marking the beginning of a long and prolific career focused almost exclusively on the city he called home.

The Parisian Panorama: Subject and Style

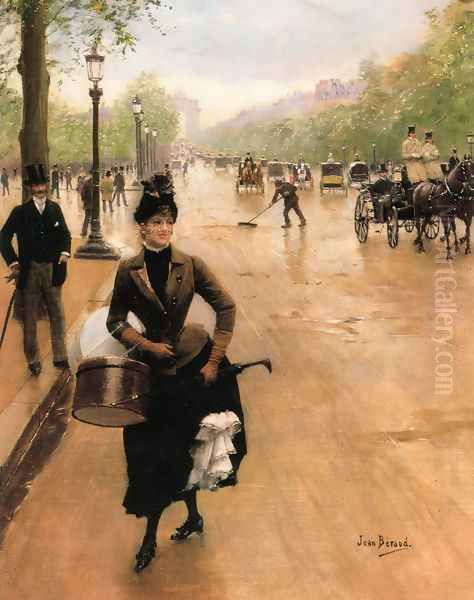

Béraud became the quintessential painter of Parisian public life. He was, in many ways, a visual equivalent of the literary flâneur – the observant wanderer who strolled the city streets, taking in the spectacle of modernity. His canvases teem with the energy and diversity of late 19th and early 20th-century Paris. He depicted the grand boulevards, recently reshaped by Baron Haussmann, bustling with pedestrians, horse-drawn carriages, and eventually, the first automobiles. Famous landmarks and gathering places frequently appear in his work, providing specific settings for his social observations.

His subject matter spanned the social spectrum, though he is perhaps best known for his depictions of the fashionable bourgeoisie and aristocracy. He painted elegant women strolling on the Champs-Élysées, crowds spilling out of the Opéra Garnier after a performance, patrons enjoying refreshments at famous cafes like Tortoni or the Café de la Paix, and intimate soirées in private homes. Yet, he also turned his attention to other aspects of Parisian life, including scenes in Montmartre, along the banks of the Seine, and occasionally, glimpses of working-class individuals or figures on the social margins, such as absinthe drinkers.

Béraud’s style was distinctive. He possessed a remarkable ability to render detail with near-photographic precision, capturing the specifics of fashion, architecture, and physiognomy. This commitment to realism aligned him partly with the academic tradition of his teacher, Bonnat, and artists like Jean-Léon Gérôme. However, Béraud infused these detailed scenes with a sense of immediacy and atmosphere often associated with Impressionism. He paid close attention to light effects, whether the gaslight illuminating a boulevard at night or the daylight filtering into a cafe. While not employing the broken brushwork of Claude Monet or Pierre-Auguste Renoir, his handling could be lively, contributing to the feeling of a captured moment.

Capturing the Belle Époque: Narrative and Observation

Unlike many Impressionists who focused primarily on visual sensation, Béraud often embedded subtle narratives and social commentary within his detailed scenes. His paintings frequently invite viewers to speculate about the relationships and interactions between the figures depicted. He had a keen eye for social nuance, capturing the gestures, postures, and expressions that revealed class distinctions, social rituals, and fleeting encounters. There is often a theatrical quality to his compositions, as if presenting vignettes from the ongoing performance of Parisian life.

His work provides an invaluable visual record of the Belle Époque – its fashions, its modes of transport, its social customs, and its changing urban landscape. He documented the rise of leisure culture, the importance of public spaces for social interaction, and the sheer visual richness of the modern city. While artists like Gustave Caillebotte also depicted Haussmann's Paris, Béraud's focus was often more on the human element within the grand new city, capturing the pulse of its social life with wit and precision. His detailed approach differed significantly from the more subjective and light-focused cityscapes of Monet or Camille Pissarro.

Key Works and Defining Themes

Several paintings stand out as representative of Béraud's oeuvre and his fascination with Parisian life. La Pâtisserie Gloppe (c. 1889) is a prime example, depicting elegantly dressed patrons inside a renowned pastry shop on the Champs-Élysées. The meticulous rendering of the cakes, the fashionable attire, and the interactions between customers and staff showcases Béraud's skill in capturing both material detail and social atmosphere. It’s a snapshot of bourgeois indulgence and leisure.

His numerous depictions of the Sortie de l'Opéra (Leaving the Opera) capture the excitement and social importance of attending the theatre. These paintings often show crowds of top-hatted men and elegantly gowned women spilling onto the floodlit pavement, hailing carriages under the imposing facade of the Palais Garnier. Béraud masterfully conveys the crush of people, the play of artificial light, and the sense of occasion, contrasting with the looser, more atmospheric crowd scenes painted by Renoir.

Béraud also painted the famous boulevards themselves, such as Le Boulevard des Capucines. His versions stand in contrast to Monet's iconic Impressionist view from Nadar's studio. Where Monet captured the fleeting impression of movement and light, Béraud focused on the specific individuals and interactions along the bustling street, offering a more detailed, anecdotal perspective on the same location.

A particularly notable and controversial work is Mary Magdalene in the House of the Pharisees (1891). Béraud audaciously transposed the biblical scene into a contemporary Parisian setting, depicting Christ and his disciples dining, while Mary Magdalene kneels before them, in what appears to be a fashionable modern restaurant or cafe (often identified as the Café Anglais). This juxtaposition of the sacred and the profane shocked many critics and members of the public, who saw it as blasphemous. However, it also highlighted Béraud's willingness to engage with contemporary morality and use historical or religious themes for social commentary, a trait shared, albeit in different ways, by artists like Édouard Manet.

Other recurring themes include cafe interiors, scenes along the Seine, depictions of racetracks, and portraits, all contributing to his comprehensive visual survey of Paris. Works like Une Soirée (An Evening) capture the ambiance of high-society gatherings, while paintings featuring absinthe drinkers touch upon the darker side of modern urban life, a theme also explored by Manet and Edgar Degas.

Béraud and His Contemporaries: Connections and Contrasts

Jean Béraud navigated the complex Parisian art world of his time, maintaining connections across different artistic circles. His training with Léon Bonnat placed him initially within the academic sphere. However, his choice of modern subject matter and his observational style brought him into proximity with the Impressionists and other painters of modern life. He was known to be a close friend of Édouard Manet, a pivotal figure who bridged Realism and Impressionism and shared Béraud's interest in depicting contemporary Parisian society, cafes, and social rituals.

Béraud frequented the same cafes, theaters, and social spots as many leading artists of the day. Sources indicate he socialized with figures like Edgar Degas, whose interest in capturing movement, artificial light, and scenes of modern entertainment (like the opera and cafes) paralleled Béraud's, although Degas employed more innovative compositional strategies and a different psychological intensity. He would have also encountered Pierre-Auguste Renoir, known for his vibrant depictions of Parisian leisure, though Renoir's style was distinctly more Impressionistic and focused on warmth and sensuality.

While influenced by the Impressionists' focus on contemporary life and light, Béraud never fully adopted their techniques. He maintained a level of finish and detail that appealed to the Salon juries and a broader public, distinguishing his work from the looser brushwork of Monet or Pissarro. His detailed realism sometimes drew comparisons to contemporaries like James Tissot or the Belgian Alfred Stevens, who also specialized in elegant scenes of modern life and fashion. He shared subject matter – the modern city – with Gustave Caillebotte, but Caillebotte's work often featured more dramatic perspectives and a cooler sense of detachment.

His social connections extended beyond the visual arts. He was notably a witness (or second) for the writer Marcel Proust during a duel Proust fought in 1897. This anecdote places Béraud firmly within the sophisticated literary and social circles of fin-de-siècle Paris, the very world Proust would later immortalize in In Search of Lost Time. Béraud's network also included collectors like Armand Dorville and society figures such as Princess Eugénie de Murat.

He was also actively involved in the institutional structures of the art world. Béraud was a founding member of the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts (SNBA) in 1890. This society was established as a more liberal alternative to the official Salon, led by artists like Ernest Meissonier, Puvis de Chavannes, and Auguste Rodin. Béraud exhibited regularly with the SNBA from its inception until 1929, demonstrating his alignment with artists seeking greater independence while still operating within a recognized framework.

Recognition, Awards, and the Writer's Eye

Béraud achieved considerable success and recognition during his lifetime. His detailed and engaging depictions of Parisian life were popular with the public and critics who appreciated his technical skill and relatable subject matter. A significant mark of official approval came in 1889, a year of great importance for Paris with the Exposition Universelle (World's Fair) and the unveiling of the Eiffel Tower. At this exposition, Béraud was awarded a Gold Medal for his work. In the same year, he was made a Chevalier of the Légion d'Honneur, one of France's highest civilian honours, cementing his status within the established art world.

Interestingly, Béraud's creative output was not limited to painting. He was also a writer, producing novels and essays. While perhaps less known than his paintings, his literary work reportedly shared the same sharp observational quality and sometimes satirical edge found in his visual art. One source mentions a novel titled La Vitrioleuse, noted for its biting satire, though details about its publication or potential controversy remain somewhat obscure. This dual role as painter and writer underscores his deep engagement with the social fabric and narratives of his time. His controversial painting Mary Magdalene in the House of the Pharisees can also be seen through this lens – an artist using his medium not just to depict, but to comment and provoke thought, much like a social critic or satirist might in writing.

Later Life and Enduring Legacy

Jean Béraud continued to paint actively into the early 20th century, witnessing the twilight of the Belle Époque and the profound changes brought by the First World War. He remained faithful to his Parisian subjects, though the world he depicted was inevitably transformed by time and events. He passed away in his beloved Paris in 1935 at the age of 86, leaving behind a vast body of work.

While during the height of modernism in the early 20th century, Béraud's more traditional style might have been somewhat overshadowed by the avant-garde movements, his reputation has endured and arguably grown over time. Art historians and the public increasingly appreciate his unique contribution. He is valued not only for his artistic skill but also as an unparalleled visual historian of Belle Époque Paris. His paintings offer a detailed, evocative, and often charming window onto a specific time and place, capturing the atmosphere, fashions, and social dynamics of the era with remarkable fidelity.

Today, Jean Béraud's works are held in the collections of major museums around the world, including the Musée d'Orsay and the Musée Carnavalet (the museum of the history of Paris) in Paris, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the National Gallery in London, and the Louvre. His paintings continue to fascinate viewers with their intricate detail, lively characterizations, and nostalgic glimpse into the bustling streets and elegant interiors of Paris during one of its most celebrated periods.

Conclusion: A Unique Vision of Paris

Jean Béraud occupies a unique position in late 19th and early 20th-century French art. He successfully navigated the space between academic tradition and modern artistic currents. While trained in a formal style, he embraced the contemporary city as his primary subject, much like the Impressionists, but rendered it with a precision and narrative focus that set him apart. He was neither a staunch academician nor a revolutionary Impressionist, but rather a masterful observer who developed a style perfectly suited to his goal: chronicling the multifaceted life of Paris during the Belle Époque. His legacy is that of a dedicated and insightful painter who left behind a rich, detailed, and invaluable visual record of a bygone era, capturing the spirit of Parisian modernity with charm, wit, and remarkable skill.