Henry d'Estienne (1872-1949) stands as a fascinating, if somewhat enigmatic, figure in the landscape of late 19th and early 20th-century French art. His work is distinguished by a compelling duality, a harmonious yet distinct exploration of two vastly different worlds: the sun-drenched, exotic allure of Orientalism and the rugged, authentic charm of Brittany. This unique blend, often pursued with almost equal dedication, allowed d'Estienne to carve out a niche for himself, offering viewers a rich tapestry woven from threads of distant cultures and deeply rooted local traditions. While not always in the vanguard of avant-garde movements, his commitment to these themes, coupled with a versatile skill set that extended to portraiture, landscape, and genre scenes, marks him as an artist worthy of deeper appreciation. His paintings serve as windows into both the romanticized visions of the East held by many Europeans of his time and a heartfelt portrayal of the enduring spirit of one of France's most culturally distinct regions.

The Artistic Milieu: Fin-de-Siècle France

To understand Henry d'Estienne's artistic journey, one must consider the vibrant and rapidly evolving art world of France during his formative years. Born in 1872, d'Estienne grew up in an era where the dust of Impressionism was settling, and new movements were constantly challenging established norms. The official Salons still held sway, but their dominance was increasingly contested by independent exhibitions and a burgeoning gallery scene. Artists like Claude Monet and Pierre-Auguste Renoir had already revolutionized the perception of light and color, while Post-Impressionists such as Paul Cézanne, Vincent van Gogh, and Paul Gauguin were pushing the boundaries of form, expression, and subject matter.

It was a time of immense artistic ferment. The academic tradition, with its emphasis on historical and mythological scenes, was still taught at institutions like the École des Beaux-Arts, but many young artists sought alternative paths. Symbolism, with figures like Gustave Moreau and Odilon Redon, offered a retreat into dreamlike, mystical realms. Simultaneously, a fascination with the "primitive" and the "exotic" was taking hold, fueled by colonial expansion and increased global travel. This environment, rich with diverse influences and competing aesthetics, would have provided a stimulating, if complex, backdrop for an emerging artist like d'Estienne.

The Lure of the Orient: D'Estienne's Eastern Visions

Orientalism, as an artistic movement, had been a significant force in French art since the early 19th century, pioneered by artists like Eugène Delacroix with his groundbreaking trip to Morocco and Algeria. By d'Estienne's time, it had evolved, but the fascination with North Africa, the Middle East, and other "Eastern" lands remained potent. These regions offered European artists a perceived escape from the industrializing West, a world of vibrant colors, different customs, and what was often romanticized as a more "authentic" or "timeless" way of life. Artists like Jean-Léon Gérôme had built entire careers on meticulously detailed, often highly theatrical, depictions of Oriental scenes.

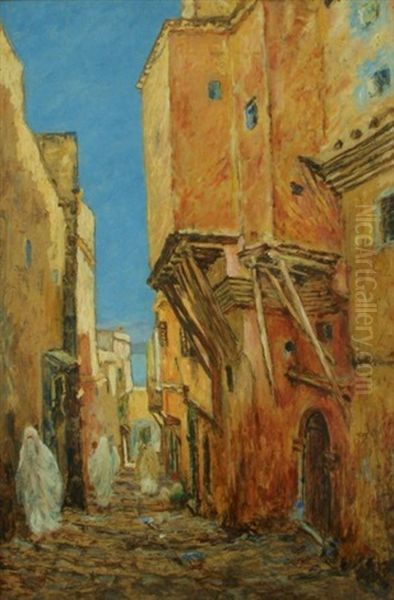

Henry d'Estienne was clearly captivated by this allure. His work, Ruelle dans la Casbah d'Alger (Alley in the Casbah of Algiers), an oil painting measuring 69x46 cm, is a prime example of his engagement with Orientalist themes. Though we lack a visual of this specific piece, the title itself evokes a classic Orientalist subject. The Casbah of Algiers, with its labyrinthine alleys, bustling crowds, and unique architecture, was a magnet for artists. One can imagine d'Estienne capturing the play of intense sunlight and deep shadow, the textures of ancient walls, and perhaps glimpses of daily life unfolding within this historic quarter.

His approach might have shared sensibilities with contemporaries like Étienne Dinet (Nasreddine Dinet), who immersed himself in Algerian culture and often depicted everyday life with a degree of empathy, or Jacques Majorelle, known for his vibrant depictions of Morocco, particularly the intense blues that would later bear his name. Unlike some earlier Orientalists whose work could be criticized for perpetuating stereotypes, artists of d'Estienne's generation sometimes sought a more nuanced, though still inherently "outsider," perspective. D'Estienne's Algerian scenes would have contributed to this ongoing visual dialogue, offering his personal interpretation of a land that continued to fascinate the European imagination. Other notable Orientalist painters whose influence or parallel work might be considered include Eugène Fromentin, known for his desert scenes, and Gustave Guillaumet, who also focused on Algerian life.

The Call of Brittany: Capturing a Rugged Authenticity

Parallel to his Orientalist pursuits, Henry d'Estienne was deeply drawn to Brittany. This region in northwestern France, with its distinct Celtic heritage, rugged coastline, traditional costumes, and deeply religious populace, had become another significant artistic hub by the late 19th century. Artists, weary of Parisian sophistication or seeking a "purer" subject matter, flocked to Brittany, particularly to towns like Pont-Aven. Paul Gauguin and Émile Bernard famously developed Synthetism there, characterized by bold outlines, flat areas of color, and a move away from naturalistic representation.

D'Estienne's painting, Moutons en Berdage (Sheep by the Sea/Coastal Sheep), an oil measuring 53x47 cm, firmly places him within this Breton tradition. The title suggests a pastoral scene, likely depicting sheep grazing near the dramatic Breton coast. This subject matter was popular among artists who sought to capture the traditional agricultural life of the region, often imbued with a sense of timelessness and connection to the land. One can envision a composition where the hardy sheep are set against a backdrop of windswept cliffs, a turbulent sea, or the soft light of a Breton sky.

His Breton works would have resonated with the efforts of painters like Henri Moret or Maxime Maufra, who, though influenced by Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, dedicated much of their careers to capturing the unique landscapes and light of Brittany. These artists, and d'Estienne among them, were not necessarily part of the radical Pont-Aven School, but they contributed to a broader appreciation of Brittany's distinct character. They depicted its fishing villages, its pardons (religious festivals), and its resilient people, often with a focus on the atmospheric conditions and the enduring human presence in a sometimes harsh environment. The work of Ferdinand du Puigaudeau, known for his depictions of Breton festivals and night scenes, also falls within this sphere of interest.

A Synthesis of Styles: Versatility in Portraiture and Genre

Beyond his primary focuses on Orientalist and Breton themes, Henry d'Estienne was also a skilled portraitist and painter of genre scenes. This versatility is significant, as it demonstrates a broader artistic capability and an ability to adapt his observational skills to different subjects. His portraits, while less documented in the provided information, would likely have reflected the prevailing tastes of the era, perhaps combining a degree of psychological insight with a competent rendering of likeness and attire.

The ability to work across different genres – from the exoticism of Algiers to the rustic charm of Brittany, and then to the more intimate focus of portraiture – suggests an artist who was not dogmatically tied to a single mode of expression. Instead, he seems to have been driven by a curiosity for different environments and human experiences. This adaptability allowed him to explore the "Eastern" and "Western" poles of his artistic interests without necessarily forcing an unnatural fusion in every single work. Rather, he could dedicate specific canvases to specific explorations, allowing the unique character of each subject to dictate the approach.

His genre scenes, whether set in North Africa or Brittany, would have provided opportunities to narrate aspects of daily life, cultural practices, or social interactions. These works often bridge the gap between pure landscape and pure portraiture, offering a more holistic view of the communities and environments he depicted.

Artistic Techniques and Characteristics

While detailed analyses of d'Estienne's specific techniques are scarce in the provided material, we can infer certain characteristics based on his chosen subjects and the prevailing artistic trends. For his Orientalist works, one might expect a rich color palette, attention to the effects of strong sunlight and shadow, and a focus on capturing the textures of fabrics, architecture, and decorative elements. The tradition of Orientalist painting often emphasized a high degree of finish and detail, though by d'Estienne's time, looser, more impressionistic handling was also common.

In his Breton scenes, the approach might have varied. The ruggedness of the landscape and the often muted, atmospheric light of Brittany could inspire a more subdued palette, perhaps with an emphasis on earthy tones and the blues and grays of the sea and sky. The influence of Post-Impressionist tendencies in Brittany might have led to stronger outlines or a simplification of forms, though this is speculative without seeing the works. His oil paintings, such as Ruelle dans la Casbah d'Alger and Moutons en Berdage, indicate a preference for this traditional medium, which offered rich possibilities for color blending, impasto, and detailed rendering.

The "almost equal" presence of Orientalist and Breton themes in his oeuvre suggests a deliberate and sustained engagement with both. This wasn't a fleeting interest in one or the other, but rather two parallel tracks that defined his artistic identity. The challenge for an artist like d'Estienne would have been to imbue both types of scenes with a sense of authenticity and personal vision, moving beyond mere picturesque representation.

D'Estienne in the Context of His Contemporaries

Placing Henry d'Estienne within the broader context of his contemporaries helps to illuminate his artistic choices. The late 19th and early 20th centuries were a period of extraordinary artistic diversity in France. While the Impressionists had broken new ground, their influence was being absorbed and transformed by a new generation.

In the realm of Orientalism, d'Estienne was working in a field that had already seen giants like Delacroix and Gérôme, and was populated by contemporaries such as Dinet, Majorelle, Ludwig Deutsch, and Rudolf Ernst, many of whom specialized almost exclusively in Eastern subjects, often with a highly polished, academic technique. D'Estienne's contribution would have been his particular way of seeing and rendering these familiar tropes.

In Brittany, he was part of a wave of artists drawn to the region. While Gauguin, Bernard, and Paul Sérusier (a key figure in the Nabis group, which grew out of Pont-Aven ideas) were pursuing more radical stylistic innovations, many other painters, like Moret, Maufra, and Gustave Loiseau, were developing their own interpretations of Breton landscapes and life, often blending Impressionist techniques with a deeper sense of place. D'Estienne's Breton works would align more closely with this latter group, focusing on capturing the visual and cultural essence of the region.

It's also worth noting artists who, like d'Estienne, explored diverse geographical or thematic interests. For instance, Théodore Chassériau, though earlier, had notably combined a Neoclassical training with Romantic and Orientalist themes. The very act of dividing his attention between such distinct locales as Algeria and Brittany set d'Estienne apart from artists who dedicated their entire careers to a single region or genre. This breadth, while perhaps preventing him from being solely identified with one "school," speaks to a wide-ranging curiosity.

Legacy and Reception

The legacy of an artist like Henry d'Estienne, who balanced distinct thematic interests rather than aligning with a single dominant movement, can be complex. Artists who are easily categorized often find a more straightforward path into art historical narratives. However, d'Estienne's body of work offers a valuable perspective on the artistic currents of his time. His engagement with Orientalism reflects the enduring European fascination with the East, while his Breton scenes contribute to the rich visual record of France's diverse regional cultures.

The fact that his works, such as Ruelle dans la Casbah d'Alger and Moutons en Berdage, are documented with their dimensions and medium suggests they found their way into collections and were considered significant enough to be recorded. The art market for both Orientalist and Breton scenes has seen periods of fluctuating interest, but there remains a consistent appreciation for well-executed examples from these genres.

Artists like d'Estienne, who may not have been radical innovators but were skilled practitioners working within established yet evolving traditions, play a crucial role in fleshing out our understanding of an artistic era. They demonstrate how broader trends were interpreted and personalized by individual talents. His dual focus provides a particularly interesting case study, highlighting the diverse inspirations available to a French artist at the turn of the 20th century. The "fusion of Eastern and Western cultural elements" noted in his work points to an artist grappling with and expressing the growing interconnectedness of the world, even as he also celebrated distinct local identities.

Conclusion: An Artist of Two Worlds

Henry d'Estienne (1872-1949) emerges as an artist who navigated two compelling, yet geographically and culturally disparate, sources of inspiration. His canvases captured the vibrant, sun-baked alleys of Algiers and the windswept, pastoral landscapes of Brittany, demonstrating a remarkable ability to shift his focus and adapt his painterly voice to the demands of each unique environment. While perhaps not a revolutionary figure in the annals of art history, his dedication to these distinct themes, his versatility in portraiture and genre, and his skillful execution in oil painting mark him as a noteworthy contributor to the French art scene of his time.

His work invites us to consider the multifaceted nature of artistic inspiration and the ways in which artists can draw from diverse wells of experience. In an era of rapid change and artistic experimentation, d'Estienne chose paths that, while well-trodden by some, still offered ample room for personal expression. He reminds us that the artistic landscape is composed not only of its towering peaks but also of the many skilled and dedicated artists who explore its varied terrains, leaving behind a legacy that enriches our understanding of the past. Henry d'Estienne's paintings, straddling the exoticism of the Orient and the rootedness of Brittany, offer a unique and engaging vision, a testament to an artist who found beauty and meaning in contrasting worlds.