Jean Launois stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in early 20th-century French art. His life, spanning a tumultuous period in European history, and his artistic journey, which took him from the academic studios of Paris to the vibrant landscapes and cultures of North Africa, offer a compelling narrative. Launois was an artist of keen observation, a draughtsman of exceptional skill, and a painter who captured the essence of his subjects with both realism and a distinctive elegance. His legacy is one of rich visual documentation, particularly of Algeria, and a body of work that continues to resonate with collectors and art enthusiasts.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Jean Launois was born on May 7, 1898. While some sources suggest a birthplace in the Vendée region, more detailed records point to Paris as his city of birth. His early artistic inclinations led him to the French capital's vibrant art scene, a crucible of innovation and tradition. Launois enrolled at the prestigious Académie Julian, a private art school that, since its founding in 1867, had become a vital alternative to the more rigid École des Beaux-Arts. The Académie Julian was renowned for its progressive atmosphere, attracting students from across France and internationally, including figures who would later become luminaries, such as Henri Matisse, Pierre Bonnard, Édouard Vuillard, and Fernand Léger, though their paths and styles would diverge significantly from Launois's more representational approach.

At the Académie Julian, Launois benefited from the tutelage of established artists. Among his mentors were Charles Milcendeau (sometimes recorded as Milcendoeuf) and Auguste Lepère. Milcendeau, himself a native of the Vendée region, was known for his sensitive portrayals of peasant life and regional customs, often working in pastels and oils. His influence might have instilled in Launois an appreciation for capturing the character of specific communities and individuals. Auguste Lepère, on the other hand, was a master printmaker, illustrator, and painter, celebrated for his wood engravings and his depictions of Parisian life and rural landscapes. Lepère's emphasis on strong draughtsmanship and compositional clarity likely left a lasting mark on Launois's developing style. This foundational training provided Launois with a robust technical skill set, particularly in drawing, which would become a hallmark of his work.

The Interruption of War and a Return to Art

The outbreak of the First World War in 1914 dramatically altered the course of countless lives, and Jean Launois was no exception. His burgeoning artistic career was put on hold as he was called to serve his country. During the conflict, Launois was involved in camouflage operations. This unique and often hazardous duty required a keen understanding of visual deception, an eye for landscape, and the ability to manipulate appearances – skills that, while applied to a grim purpose, paradoxically resonated with certain aspects of artistic practice. The war years were undoubtedly formative, exposing him to realities far removed from the art studio and likely deepening his understanding of the human condition.

Following the armistice in 1918, Launois, like many of his generation, faced the task of rebuilding his life and career. He did not immediately resettle into the Parisian art world but was drawn to new horizons. His experiences during the war may have broadened his perspective or perhaps instilled a desire to explore beyond the familiar. It was during this post-war period that his profound connection with North Africa, particularly Algeria, began to take shape. This region would become a central focus of his artistic output and a source of enduring inspiration.

The Allure of Algeria: A New Artistic Chapter

Algeria, then a French colony, held a powerful exotic allure for many European artists, a tradition dating back to Romantic painters like Eugène Delacroix, whose 1832 trip to Morocco and Algeria had a transformative impact on his art and on the Western perception of the "Orient." Later in the 19th century, artists such as Jean-Léon Gérôme and Gustave Guillaumet further popularized North African subjects, often emphasizing the picturesque, the dramatic, or the ethnographic. By the time Launois began his travels, a distinct school of French Orientalist painting was well-established, with artists like Étienne Dinet (who converted to Islam and lived in Algeria) and Jacques Majorelle (known for his vibrant depictions of Morocco) being prominent figures.

Launois immersed himself in Algerian culture, traveling extensively and observing the daily life, customs, and diverse peoples of the region. He was not merely a tourist with a sketchbook; he engaged in a deeper study, seeking to understand the nuances of the societies he encountered. His approach was characterized by a respectful curiosity and a desire to portray his subjects with dignity. This deep engagement distinguished his work from some of the more superficial or stereotyped representations of North Africa prevalent at the time. His depictions of Algerian life went beyond mere exoticism, aiming for a more authentic and empathetic portrayal. This commitment to understanding the local culture made him an authority on the subject, and his insights were valued not only by fellow artists but also by writers and poets, such as Gabriel Audisio, who wrote about his work.

His travels were not limited to Algeria; he also spent time in Tunisia and Morocco, further broadening his understanding of the Maghreb. These experiences provided him with a rich tapestry of subjects: bustling marketplaces, quiet domestic scenes, portraits of individuals from various walks of life, and the distinctive landscapes of the region.

Artistic Style: Realism, Line, and Medium

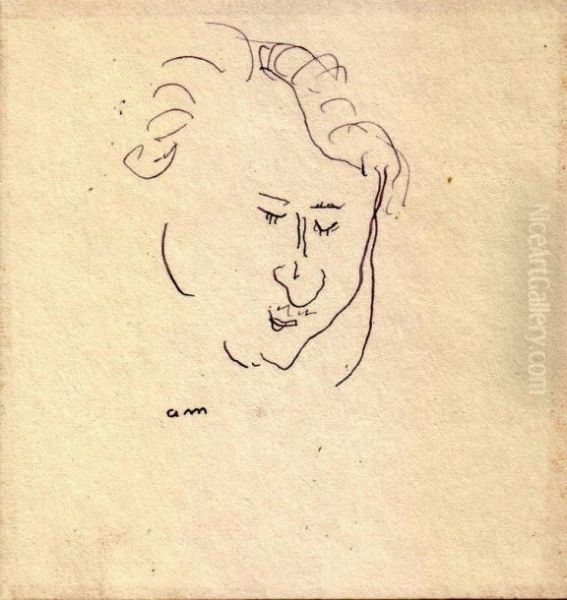

Jean Launois's artistic style is primarily rooted in Realism, but it is a realism infused with a distinct elegance and a remarkable sensitivity, particularly in his rendering of the human form and face. His academic training is evident in his skilled draughtsmanship. The line in Launois's work is often paramount – fluid, confident, and descriptive. Whether in quick sketches or more finished drawings, his ability to capture character and form with a few well-placed lines is consistently impressive.

He was proficient in a variety of media. Pencil and black ink were frequently used for his drawings and studies, allowing for precision and expressive mark-making. One of his most noted works, the "Portrait of a One-Eyed Man," executed in pencil and black ink (139 x 120 mm), exemplifies his mastery in capturing intense character and psychological depth with economical means. He also worked extensively in watercolor, a medium well-suited to capturing the light and atmosphere of North Africa, and in oils, which allowed for richer textures and more complex compositions.

While Realism was his foundation, his work was not photographic. There is a subtle stylization, an elegance in his figures that elevates them beyond simple documentation. His compositions are carefully considered, and there's a quiet dignity in his portrayals, even of the most humble subjects. He avoided the overt sentimentality that could sometimes affect realist painters, instead imbuing his figures with a sense of presence and individuality. His approach can be seen as part of a broader early 20th-century trend that, while moving away from the avant-garde experiments of Cubism or Fauvism (as practiced by artists like Georges Braque or André Derain), still sought a modern voice within more traditional representational frameworks, akin perhaps to some aspects of the "Return to Order" movement that gained traction after WWI.

Key Themes and Celebrated Works

Thematic consistency is a strong feature of Launois's oeuvre. Portraits and figure studies form a significant portion of his output. He had a remarkable ability to capture not just a likeness but the personality and inner life of his sitters. His depictions of Algerian men and women are particularly noteworthy, showcasing a wide range of human types and expressions, from contemplative elders to vibrant youths.

Beyond individual portraits, Launois was drawn to scenes of everyday life. Works like "The Couple" and "Two Women in a Café" (the latter perhaps echoing the café scenes of Impressionists like Edgar Degas or Post-Impressionists like Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, albeit in a different cultural context and style) provide glimpses into social interactions and quiet moments. "A Young Girl and a Dog" (or "A Young Girl and Her Dog") suggests a more tender, intimate side to his observations. These paintings, often characterized by their strong compositions and empathetic portrayals, have found homes in significant public collections.

His fascination with North Africa also extended to its cultural expressions. He depicted local attire, marketplaces, and traditional activities, contributing to a visual record of a society undergoing change. The series of works titled "Les Sables d'Olonne" indicates that he also painted scenes from his native France, perhaps from the Vendée region, showcasing his versatility in capturing different environments. Later in his career, particularly in the 1930s, Launois also turned his talents to illustration, providing drawings for literary works. This endeavor would have drawn upon his strong narrative sense and his skill in character depiction.

Interestingly, his artistic explorations were not confined to North Africa. Evidence suggests he also developed an understanding of and depicted Vietnamese culture, creating portraits of Vietnamese women. This indicates a broader curiosity about non-European cultures and a capacity to adapt his observational skills to different contexts.

Exhibitions, Recognition, and Later Life

Jean Launois achieved a notable degree of recognition during his lifetime. A significant milestone was his solo exhibition in 1931 at the prestigious Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris. To have a one-man show at such an institution was a clear acknowledgment of his standing in the Parisian art world. His works were also exhibited in Algiers, notably at the Abbaye de Saint-Croix museum, underscoring his strong connection to the Algerian art scene and his reputation as a chronicler of its life and people.

His paintings and drawings have continued to be sought after, frequently appearing in auction catalogues and commanding respectable prices. The consistent presence of his work in the art market speaks to its enduring appeal to collectors who appreciate his technical skill, his sensitive portrayals, and the historical and cultural significance of his North African subjects. The art world's evaluation of Launois centers on his profound observation, his elegant fusion of realism with expressive line, and his contribution to the Orientalist genre, albeit with a more nuanced and empathetic perspective than some of his predecessors or contemporaries.

There is also a curious anecdote involving a collaboration with a collector named Bernard Launois (it is unclear if they were related). Together, they reportedly created an artwork using 37,000 champagne caps. While perhaps an eccentric departure from his primary artistic practice, it hints at a playful or experimental facet to his personality and an engagement with the world of collecting.

The final years of Jean Launois's life are set against the backdrop of another global conflict, the Second World War. According to the most detailed records, Jean Launois passed away on December 15, 1944, in Ellrich, Germany. Ellrich was the site of a subcamp of the Mittelbau-Dora concentration camp, a place of immense suffering. If his death occurred there, it adds a tragic and poignant end to the life of an artist dedicated to observing and celebrating humanity. This contrasts with earlier accounts suggesting he died in 1942. The circumstances surrounding his presence and death in Ellrich, if accurate, remain a somber chapter requiring further historical clarification but point to the devastating reach of the war.

Launois in the Context of His Contemporaries

To fully appreciate Jean Launois, it's useful to consider him within the broader artistic landscape of his time. While studying at the Académie Julian, the Parisian art world was a ferment of activity. Fauvism, with its bold colors (Matisse, Derain), had already made its impact, and Cubism (Picasso, Braque) was revolutionizing pictorial space. However, Launois, like many artists, pursued a more representational path.

His focus on North Africa places him in the lineage of Orientalist painters. He can be compared to artists like Étienne Dinet, who also dedicated much of his life to depicting Algeria with an insider's perspective, or Jacques Majorelle, whose Moroccan works are famed for their intense blues. However, Launois's style was generally more subdued and linear than Majorelle's vibrant decorative approach, and perhaps less romanticized than some of Dinet's earlier works. He shared with them a deep fascination for the region but brought his own distinct observational acuity.

In Paris, during the interwar period, artists like Kees van Dongen, though associated with Fauvism, also produced society portraits with a characteristic flair. The School of Paris included many émigré artists such as Moïse Kisling and Chaïm Soutine, who brought different expressive and figurative styles to the fore. Launois's work, with its emphasis on realism and classical draughtsmanship, offered a different sensibility, perhaps aligning more with artists who maintained a connection to traditional skills while exploring contemporary subjects. His dedication to capturing specific cultural identities could also be seen as a form of regionalism, a trend present in various parts of Europe and America during this period, where artists focused on the unique character of their local environments or specific communities.

His teachers, Charles Milcendeau and Auguste Lepère, provided a direct lineage. Milcendeau's focus on regional French life and Lepère's mastery of printmaking and urban scenes both contributed to Launois's development. Lepère, in particular, was part of a revival of original printmaking, and his influence might be seen in Launois's strong graphic sense.

Enduring Legacy

Jean Launois left behind a significant body of work that serves as both an artistic achievement and a valuable historical document. His paintings and drawings offer a window into the cultures he observed, particularly that of Algeria in the early to mid-20th century. He approached his subjects with a rare combination of technical skill and human empathy, creating portraits and scenes that are both aesthetically pleasing and emotionally resonant.

His commitment to realism, refined by an elegant sense of line and composition, ensured the accessibility and enduring appeal of his art. While he may not have been part of the radical avant-garde movements that often dominate art historical narratives, his contribution lies in the quality and sincerity of his vision. He successfully navigated the space between academic tradition and modern observation, creating a unique artistic voice.

The continued interest in his work at auctions and its presence in museum collections attest to his lasting importance. For art historians, he offers a case study in the evolution of Orientalism and the ways in which European artists engaged with non-Western cultures in the colonial era. For art lovers, his work provides a rich visual experience, filled with finely rendered details, compelling characters, and a palpable sense of time and place. Jean Launois's art remains a testament to a life spent observing the world with a keen eye and a skilled hand, leaving a legacy that continues to be appreciated for its beauty, its insight, and its humanity.