Henry George Keller stands as a significant, if sometimes underappreciated, figure in the landscape of American art, particularly renowned for his mastery of watercolor and his profound influence as an educator. His career spanned a transformative period in art history, from the lingering echoes of 19th-century academicism to the vibrant upheavals of modernism. Keller navigated these currents with a distinctive vision, leaving an indelible mark on the Cleveland School of Art and shaping a generation of artists. His life and work offer a fascinating study of an artist dedicated to both technical excellence and expressive power, particularly in his evocative depictions of nature and animal life.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

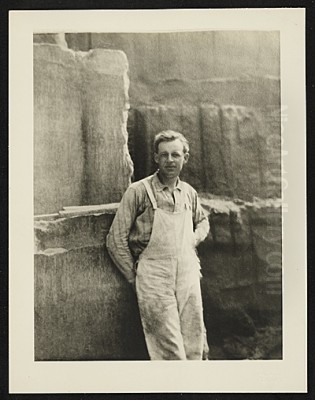

Henry George Keller's journey into the world of art began in an unconventional setting. He was born on April 3, 1869, not on solid land, but at sea, off the coast of Newfoundland, Canada. This maritime birth perhaps foreshadowed a life of movement and exploration, both geographically and artistically. His family eventually settled in Cleveland, Ohio, a city that would become central to his artistic identity and career.

Keller's formal artistic training commenced in Europe, a common path for ambitious American artists of his era seeking rigorous instruction. He traveled to Karlsruhe, Germany, where he studied under Hermann Baisch. Baisch was a respected landscape and animal painter associated with the Barbizon-influenced German plein-air movement, and his tutelage likely instilled in Keller a deep appreciation for direct observation of nature and a solid grounding in traditional techniques. This early exposure to European academic methods provided a foundational layer upon which Keller would build his evolving style.

Upon returning to the United States, Keller continued to hone his skills at several prominent institutions. He attended the Cleveland School of Art (now the Cleveland Institute of Art), which would later become his long-term professional home. He also sought instruction at the Cincinnati Art Academy, known for its strong faculty, including figures like Frank Duveneck, who had himself trained in Munich. Further enriching his education, Keller studied at the Art Students League of New York, a vital center for artistic exchange and innovation, where artists like William Merritt Chase and Kenyon Cox were influential. During this period, he also gained practical experience through an apprenticeship at the W. J. Morgan Lithograph Company in Cleveland, which would have provided him with insights into commercial art processes and graphic design, potentially influencing his later printmaking.

The Munich Experience and Return to America

A pivotal phase in Keller's artistic development was his time at the prestigious Munich Academy of Fine Arts (Akademie der Bildenden Künste München). Munich, at the turn of the century, was a major European art center, rivaling Paris in its academic rigor and attracting students from across the globe. The Academy was known for its emphasis on draftsmanship and a dark, tonal painting style, often referred to as the "Munich School," which had significantly influenced American artists like Frank Duveneck and William Merritt Chase in earlier decades. Keller's studies there, under figures like Ludwig von Löfftz and Heinrich von Zügel (a renowned animal painter), further solidified his technical proficiency and likely deepened his interest in animal subjects.

Completing his formal studies, Keller returned to the United States equipped with a comprehensive European academic training. He embarked on his teaching career in 1902 at the Pittsburgh School of Design for Women (later the Carnegie Institute of Technology's School of Applied Design). This initial foray into art education was brief, as a more significant opportunity soon arose.

A Distinguished Career in Cleveland: Teaching and Artistic Development

In 1903, Henry George Keller returned to Cleveland and joined the faculty of the Cleveland School of Art. This marked the beginning of an exceptionally long and influential teaching career that would span over four decades, until his retirement in 1945. Keller became a cornerstone of the institution, revered by students and colleagues alike for his demanding standards, his profound knowledge of art techniques, and his charismatic, if sometimes formidable, personality.

As an instructor, Keller was known for emphasizing technical mastery and a deep understanding of materials. He believed that true artistic expression could only be achieved through a solid command of craft. While he encouraged individuality, he insisted on a rigorous foundation in drawing, composition, and color theory. His teaching philosophy was less about fostering unbridled "creative genius" and more about cultivating skilled, knowledgeable artists capable of translating their vision into tangible form. This approach had a lasting impact on the character of the Cleveland School and the artists it produced.

Throughout his teaching career, Keller remained a prolific artist. He worked across various media, including oil painting, watercolor, and printmaking, particularly etching. His subject matter often revolved around landscapes, rural scenes, and, most notably, animals. He had a particular affinity for depicting horses and pigs, capturing their characteristic forms and movements with both accuracy and expressive flair. His etchings, often sketch-like in their immediacy, showcased his strong draftsmanship.

Keller's Evolving Artistic Style and Techniques

Henry George Keller's artistic style was not static; it evolved throughout his long career, reflecting his engagement with various artistic currents while retaining a distinctive personal voice. His early work, influenced by his German training under Hermann Baisch and his time in Munich, showed affinities with 19th-century realism and a touch of German Romanticism, particularly in his landscape and animal paintings. There was a solidity of form and a careful attention to detail characteristic of academic training.

As he matured, Keller, like many artists of his generation, absorbed the lessons of Impressionism, particularly its emphasis on light and color, though he was reportedly critical of what he perceived as its lack of structure. His watercolors, for which he became particularly renowned, began to show a greater freedom and luminosity. He was a master of the medium, exploring its transparent qualities to capture fleeting atmospheric effects and the vibrant hues of nature.

A significant aspect of Keller's development was his engagement with modernism. While not an avant-garde radical in the vein of European modernists like Pablo Picasso or Henri Matisse, Keller was keenly aware of contemporary artistic developments. He was particularly interested in color theory, reputedly influenced by the ideas of Paul Cézanne and theorists like Ogden Rood and Michel Eugène Chevreul. This led him to experiment with more abstract design principles and a more subjective use of color in his compositions, especially in his later watercolors. He sought to move beyond mere representation to convey the underlying structure and emotional essence of his subjects. His works often balanced a realistic depiction of the natural world with a strong sense of personal expression and a sophisticated understanding of formal artistic elements.

Keller was also known for his innovative approach to materials, sometimes combining watercolor with gouache or even oil to achieve specific textural and chromatic effects. This willingness to experiment, grounded in a thorough knowledge of his media, was a hallmark of his practice and his teaching.

The Armory Show and Engagement with Modernism

A pivotal moment in the history of American art, and one in which Henry George Keller participated, was the International Exhibition of Modern Art, famously known as the Armory Show, held in New York City in 1913, with subsequent showings in Chicago and Boston. This landmark exhibition introduced a broad American audience to European avant-garde art, including works by Post-Impressionists like Paul Cézanne, Vincent van Gogh, and Paul Gauguin, as well as Fauvists like Henri Matisse, and Cubists like Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque. The show also featured works by American modernists.

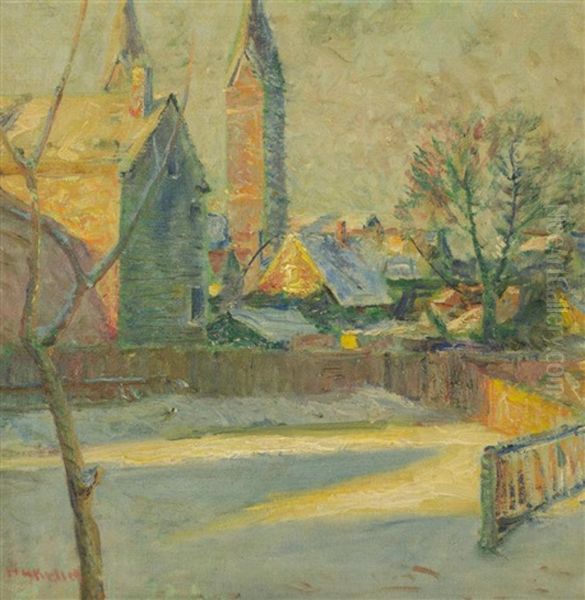

Keller exhibited two paintings at the Armory Show: "Wisdom and Destiny" and "The Valley." These works reportedly represented different facets of his artistic inclinations, with "Wisdom and Destiny" perhaps leaning towards a more traditional, allegorical style, while "The Valley" may have showcased his more modern landscape sensibilities. His inclusion in this seminal exhibition placed him among the American artists grappling with the new artistic languages emerging from Europe.

Despite his participation, Keller's relationship with the more radical forms of modernism was complex. While he embraced certain modernist principles, particularly in color and design, he remained rooted in a tradition of representational art and craftsmanship. He was reportedly critical of what he saw as the excesses of some Impressionist painters, deeming their approach too conservative or lacking in intellectual rigor. Yet, he was open to the structural innovations of Cézanne and the expressive potential of color explored by artists like Wassily Kandinsky, whose theories on the spiritual in art were gaining currency. The Armory Show undoubtedly provided a powerful stimulus for Keller, prompting him to further refine his own artistic direction in response to the seismic shifts occurring in the art world.

Notable Works and Thematic Concerns

While a comprehensive catalogue of Henry George Keller's oeuvre is extensive, certain works and themes stand out. One of his frequently cited pieces is "Lady on a Hillside with Her Parasol and Billowing Scarf." This painting, likely a watercolor, exemplifies his ability to capture a sense of atmosphere, light, and movement, blending figurative work with landscape elements in a style that could be described as a form of American Impressionism or early modernism. It showcases his skill in rendering the human form and drapery, as well as his sensitivity to the nuances of the natural environment.

Animals were a recurring and beloved theme in Keller's art. His etchings and paintings of horses, pigs, cattle, and other farm animals are particularly noteworthy. He didn't just depict their anatomical forms; he captured their essence, their characteristic postures, and their relationship to their surroundings. Works like "The Old Quarry" or various "Spanish Landscape" pieces (he traveled to Spain, which influenced his palette and subject matter) demonstrate his versatility in landscape painting, often imbued with a strong sense of place and a dynamic interplay of light and shadow.

His thematic concerns often revolved around the pastoral, the beauty of the rural landscape, and the dignity of animal life. There is a sense of deep connection to the natural world in his work, a theme that resonated with many American artists of his time who were seeking an authentic national artistic expression rooted in the American scene. Even as he incorporated modernist ideas, his art retained a fundamental respect for the observable world, filtered through his personal vision and technical prowess.

Influence as an Educator: The Keller Legacy

Perhaps Henry George Keller's most enduring legacy lies in his profound impact as an educator. Over his 45 years at the Cleveland School of Art, he mentored and inspired generations of artists, many of whom went on to achieve significant recognition. He is often credited as a foundational figure of the "Cleveland School" of artists, particularly in establishing a strong regional tradition in watercolor painting.

Among his most celebrated students was Charles Burchfield, who became one of America's foremost watercolorists, known for his visionary and often expressionistic depictions of nature and small-town America. Burchfield himself acknowledged Keller's crucial influence, particularly Keller's emphasis on direct observation and his unique methods of teaching color and composition. Another prominent student was Frank N. Wilcox, who also became a distinguished watercolorist and an influential teacher in his own right, carrying on Keller's legacy in the Cleveland area. Paul Travis, known for his paintings and prints, often inspired by his travels, was another notable artist who benefited from Keller's tutelage.

Other students who passed through Keller's classes and went on to make their mark include August F. Biehle, known for his vibrant Post-Impressionist landscapes; William Joseph Eastman; and Grace V. Kelly. These artists, while developing their own distinct styles, often reflected Keller's emphasis on strong technique, a keen observation of nature, and an intelligent use of color. Keller's summer art school, often held in Berlin Heights, Ohio, became a legendary incubator for young talent, providing an immersive environment for plein-air painting and intensive study.

His teaching methods, which combined rigorous discipline with an encouragement of individual exploration (once foundational skills were mastered), helped to create a vibrant artistic community in Cleveland. He fostered an environment where technical excellence was valued, and where watercolor was elevated as a serious medium for artistic expression.

Later Years, Recognition, and Challenges

Henry George Keller's contributions to American art did not go unrecognized during his lifetime. He exhibited widely, not only in Cleveland but also in major art centers like Chicago and New York, and his work was acquired by various museums and private collectors. A significant honor came in 1939 when he was elected an Academician by the National Academy of Design in New York, a prestigious acknowledgment of his status in the American art world. This recognition underscored his achievements both as a painter and as a respected figure in art education.

However, Keller's later years were not without challenges. Like many artists, he faced economic hardships, particularly during the Great Depression. It is documented that he experienced bankruptcy in 1936, which led to the loss of his studio and gallery. Such a setback would undoubtedly have been a significant blow, both personally and professionally, potentially impacting his artistic production and his ability to promote his work.

There have also been observations by some art historians that the quality or innovative spark of his work may have diminished somewhat in his very late career, a phenomenon not uncommon among artists who have had long and productive lives. Nevertheless, his overall body of work and his immense contribution as a teacher remained substantial. He continued to be an active member of the Cleveland artistic community, including his involvement with groups like the "Cleveland Independents," which sought to provide alternative exhibition opportunities for local artists.

Henry George Keller passed away in 1949, leaving behind a rich legacy of artwork and a profound influence on the course of art in Cleveland and beyond.

Keller's Place in Art History

Henry George Keller occupies a distinctive place in American art history. He is primarily celebrated as a master watercolorist who significantly advanced the medium's status and practice in the United States, particularly in the Midwest. His technical virtuosity, combined with his sensitive and often poetic interpretations of nature and animal life, secured his reputation as a leading artist of his generation.

His role as an educator is equally, if not more, significant. As the "dean" of the Cleveland School of Art for many decades, he shaped the artistic development of countless students, instilling in them a respect for craftsmanship, a deep understanding of materials, and an appreciation for the expressive possibilities of art. The success of his students, such as Charles Burchfield, Frank Wilcox, and Paul Travis, is a testament to his effectiveness as a teacher and mentor. He helped to establish Cleveland as an important regional art center with a strong tradition in watercolor painting.

While he engaged with modernism, Keller was not a radical innovator in the mold of the European avant-garde or even some of his more experimental American contemporaries like Marsden Hartley or Arthur Dove. Instead, he forged a path that synthesized traditional academic training with modernist sensibilities, creating a body of work that is both technically accomplished and expressively resonant. He can be seen as a transitional figure, bridging the 19th-century artistic traditions with the emerging modernism of the 20th century. His commitment to representing the American scene, particularly the landscapes and rural life of Ohio, also aligns him with broader trends in American art that sought to define a distinct national identity.

Conclusion

Henry George Keller's life was one of dedicated artistic pursuit and influential pedagogy. From his early studies in Germany and America to his long and distinguished career at the Cleveland School of Art, he consistently championed technical excellence and a profound engagement with the visual world. As a painter, particularly in watercolor, he created works of enduring beauty and sensitivity. As a teacher, he nurtured a generation of artists, leaving an indelible mark on the artistic landscape of Cleveland and contributing significantly to the broader narrative of American art. His legacy endures through his captivating artworks and the continuing influence of the artistic principles he so passionately espoused.