Henri Jean Guillaume Martin (1860-1943) stands as a significant, if sometimes understated, figure in the vibrant tapestry of late 19th and early 20th-century French art. A painter of immense talent and quiet dedication, Martin forged a unique path that artfully blended the luminous innovations of Impressionism and Neo-Impressionism with the poetic introspection of Symbolism. His canvases, often bathed in the warm light of Southern France, evoke a sense of serene beauty, timeless contemplation, and an idyllic vision of rural life and allegorical harmony. From grand public murals to intimate landscapes and portraits, Martin's oeuvre reflects a consistent pursuit of light, color, and emotional resonance.

Early Life and Academic Foundations in Toulouse

Henri Martin was born on August 5, 1860, in Toulouse, a city in southwestern France with a rich artistic and cultural heritage. His father was a cabinet maker, and his mother was of Italian descent. From an early age, Martin displayed a clear aptitude for drawing and a passion for art, which his family, despite their modest means, eventually supported. He enrolled at the École des Beaux-Arts in Toulouse, where he studied under the tutelage of Jules Garipuy, a painter and director of the Musée des Augustins, and a friend of Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres and Eugène Delacroix.

This early academic training provided Martin with a solid grounding in classical techniques, composition, and the traditional hierarchy of genres. Toulouse itself, with its distinctive architecture and the nearby Pyrenees, likely offered early visual inspiration. The artistic environment of the city, though provincial compared to Paris, was nonetheless active and would have exposed him to various prevailing artistic currents. His talent was recognized early, and a municipal scholarship enabled him to further his studies in the art capital of the world: Paris.

Parisian Aspirations and the Influence of Jean-Paul Laurens

In 1879, at the age of nineteen, Henri Martin arrived in Paris, eager to immerse himself in its dynamic art scene. He gained admission to the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts in Paris and entered the studio of Jean-Paul Laurens. Laurens was a highly respected academic painter, renowned for his large-scale historical and religious compositions, often characterized by their dramatic intensity and meticulous detail. He was a prominent figure in the official art world, a member of the Institut de France, and a professor at both the École des Beaux-Arts and the Académie Julian.

Under Laurens, Martin honed his skills in draughtsmanship and the grand manner of history painting. The influence of Laurens is evident in Martin's early works, which often tackled historical, mythological, or allegorical themes executed with academic precision. He began exhibiting at the Paris Salon, the official annual art exhibition, in 1880. His 1883 submission, Françoise de Rimini, a dramatic scene inspired by Dante's Inferno, earned him his first medal, signaling his arrival as a promising young talent within the academic tradition. Other early works, such as Caïn (Cain), also demonstrated his mastery of academic conventions and his ambition to succeed within the established Salon system.

The Italian Sojourn: A Catalyst for Change

A pivotal moment in Henri Martin's artistic development came in 1885 when a travel scholarship, won at the Salon, allowed him to journey to Italy. This trip proved to be a profound revelation. He immersed himself in the works of the early Italian Renaissance masters, particularly Giotto di Bondone and Masaccio. He was deeply struck by their clarity of form, the harmonious integration of figures within their settings, and the serene, almost spiritual quality of their light. Fra Angelico's frescoes also left a lasting impression.

This encounter with the Primitives, as they were often called, began to steer Martin away from the darker palette and dramatic intensity of his academic training under Laurens. He became increasingly interested in the expressive potential of light and color, and the way these elements could convey emotion and atmosphere. The sun-drenched landscapes of Italy and the luminous quality of its art provided a stark contrast to the often somber tones of academic history painting, planting the seeds for a significant stylistic shift. He began to experiment with a brighter palette and a more broken brushwork, hinting at the changes to come.

Embracing Light: The Turn to Divisionism

Upon his return to Paris, Martin continued to exhibit at the Salon, but his work began to show a distinct evolution. The late 1880s and early 1890s were a period of intense artistic ferment in Paris. Impressionism, pioneered by artists like Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, and Pierre-Auguste Renoir, had already revolutionized the way artists perceived and depicted the world, emphasizing fleeting moments and the effects of light and atmosphere. Building upon this, Georges Seurat and Paul Signac were developing Neo-Impressionism, also known as Pointillism or Divisionism, a more scientific approach to color theory where pure colors were applied in small dots or strokes, intended to blend in the viewer's eye.

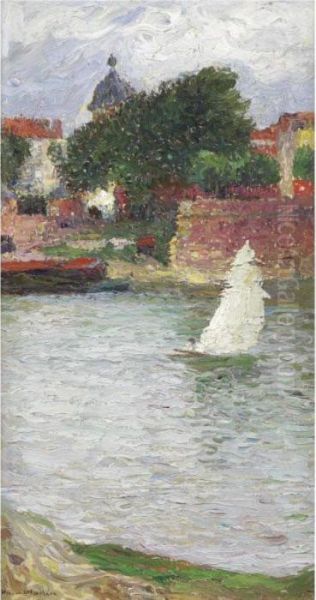

Martin was drawn to these new approaches, particularly the Neo-Impressionists' systematic use of color to achieve heightened luminosity. Around 1889, he began to adopt Divisionist techniques, though his application was often more intuitive and less rigidly scientific than that of Seurat or Signac. Instead of precise dots, Martin favored short, parallel strokes of color, which created a vibrant, shimmering surface. His painting La Fête de la Fédération (The Festival of the Federation), exhibited in 1889, marked a significant step in this direction and garnered considerable attention, winning him a gold medal at the Exposition Universelle that year.

This adoption of Divisionist principles did not mean a complete abandonment of his earlier interests. Martin skillfully integrated the new technique with his enduring concern for composition, poetic mood, and often, Symbolist themes. His Divisionism was less about optical science and more about achieving a dreamlike, ethereal quality, perfectly suited to his evolving artistic vision.

Symbolist Undercurrents and Poetic Idealism

Concurrent with his exploration of Divisionism, Henri Martin was deeply influenced by the Symbolist movement, which sought to express ideas, emotions, and spiritual truths through suggestion and evocation rather than direct representation. Artists like Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, Gustave Moreau, and Odilon Redon were key figures in this movement. Puvis de Chavannes, in particular, with his serene, classically inspired allegorical murals, had a profound impact on Martin.

Martin's work from the 1890s onwards often features Symbolist elements: melancholic muses, allegorical figures representing poetry, music, or nature, and idyllic landscapes imbued with a sense of timeless peace. His figures are often contemplative, set within harmonious, light-filled environments. He sought to create a "poetry of painting," where color and light contributed to an overall mood of serenity and introspection. Works like Sérénité (Serenity, 1899) or Vers l'Abîme (Towards the Abyss) exemplify this fusion of Divisionist technique and Symbolist sensibility. He was part of a group of artists, sometimes referred to as "Intimists" or Post-Impressionist idealists, which included his close friends Edmond Aman-Jean and Ernest Laurent, who shared similar aesthetic goals.

Major Public Commissions: Murals of Grandeur

Henri Martin's ability to synthesize modern techniques with a sense of classical harmony and allegorical meaning made him a sought-after artist for large-scale public decorations. Throughout his career, he received numerous prestigious commissions for murals in important civic buildings. These monumental works allowed him to explore grand themes and create immersive environments.

One of his most significant commissions was for the Hôtel de Ville (City Hall) in Paris, where he painted a series of panels, including Apollon et les Muses (Apollo and the Muses), completed around 1900. For the Capitole de Toulouse, the city hall of his hometown, he created a magnificent series of murals between 1895 and 1906. These works, such as Les Faucheurs (The Reapers) and La Garonne, celebrate the agricultural richness and natural beauty of the Garonne river valley and the Languedoc region. They depict idealized scenes of rural labor and bucolic landscapes, rendered in his characteristic luminous, Divisionist style.

He also created decorations for the Sorbonne in Paris and the Préfecture du Lot in Cahors. These public works cemented his reputation as a leading decorative painter of his generation, capable of adapting his style to monumental formats while retaining its poetic essence. These commissions placed him in the lineage of great French muralists, following in the footsteps of artists like Puvis de Chavannes.

The Landscapes of Southern France: Marquayrol

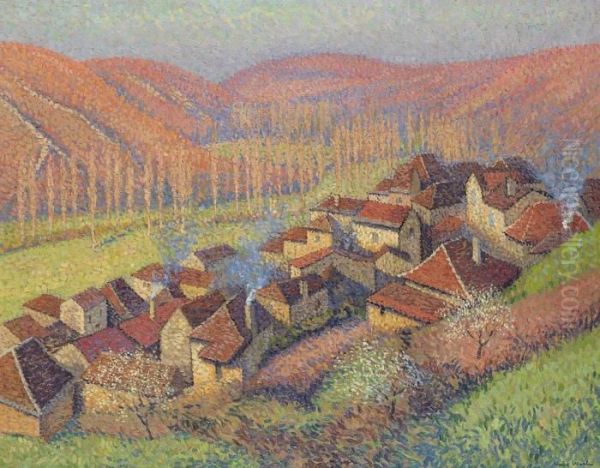

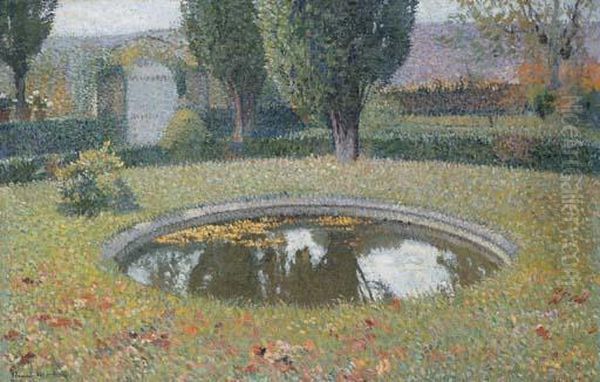

In 1900, seeking tranquility and a closer connection to nature, Henri Martin purchased a house called "Marquayrol" in Labastide-du-Vert, a picturesque village in the Quercy region of southwestern France, near Cahors. This idyllic setting, with its rolling hills, lush vegetation, and distinctive southern light, became his primary source of inspiration for the remainder of his life. He spent increasingly more time there, eventually making it his permanent residence.

The gardens and surrounding countryside of Marquayrol feature prominently in his later work. He painted numerous views of his house, its shaded arbors, sun-dappled pathways, and vibrant flowerbeds. These landscapes are characterized by their radiant light, harmonious colors, and a sense of profound peace. Works such as Le Bassin de Marquayrol (The Pool at Marquayrol) or Vue de Labastide-du-Vert capture the serene beauty of this region. His technique remained Divisionist, but perhaps softened, with a focus on capturing the atmospheric effects of light at different times of day. These paintings are intimate and personal, reflecting his deep affection for his chosen home. He also painted views of nearby Saint-Cirq-Lapopie, a stunning village perched on a cliff above the Lot River.

Portraits and Figures

While best known for his landscapes and allegorical murals, Henri Martin was also an accomplished portraitist. His portraits, often of family members, friends, or local figures from Quercy, share the same luminous quality and sensitive handling as his other works. He sought to capture not just a physical likeness but also the inner character and mood of his sitters.

His portraits of women, such as Jeune Fille à la Robe Rouge (Young Girl in a Red Dress), often have a gentle, contemplative air. He also continued to paint allegorical figures and muses, often set within his beloved landscapes of Marquayrol, further blurring the lines between genre. These figures, draped in classical attire or contemporary dress, seem to embody the spirit of the place, personifying its beauty and tranquility.

Relationships with Contemporaries

Henri Martin was well-integrated into the Parisian art world and maintained friendships with several prominent artists. His teacher, Jean-Paul Laurens, remained an important figure, even as Martin's style diverged significantly from academicism. He developed a close friendship with the sculptor Auguste Rodin; they mutually admired each other's work, and Martin's success at the 1900 Exposition Universelle, where he won a Grand Prix, coincided with Rodin's own triumphant solo exhibition.

He was also close to fellow painters Edmond Aman-Jean and Ernest Laurent, who shared his inclination towards Symbolist themes and a poetic, often idealized, vision. Perhaps his closest artistic confidant was Henri Le Sidaner. Le Sidaner, though developing his own distinct Intimist style characterized by twilight scenes and quiet, unpeopled spaces, shared with Martin a sensitivity to light, atmosphere, and a certain melancholic poetry. They were often grouped together by critics and exhibited alongside each other. While Martin's style was generally more vibrant and sunlit, especially in his later period, their shared pursuit of an art that evoked mood and emotion created a strong bond.

Martin also exhibited with the Société Nouvelle de Peintres et de Sculpteurs, a group that included artists like Charles Cottet, Lucien Simon, and Émile Claus, the Belgian Luminist whose concerns with light paralleled Martin's own. Though he adopted Divisionist techniques, he was not strictly aligned with the Neo-Impressionist group of Seurat and Signac, maintaining a more independent and lyrical approach.

Exhibitions, Recognition, and Later Life

Henri Martin achieved considerable success and recognition during his lifetime. He exhibited regularly at the Salon des Artistes Français, where he won numerous awards, including a first-class medal in 1889. He was a founding member of the Salon des Tuileries. His participation in the Exposition Universelle of 1900, where he was awarded a Grand Prix for his decorative ensemble, was a major career highlight.

He was made a Chevalier of the Legion of Honour in 1896, promoted to Officer in 1910, and eventually to Commander. In 1917, he was elected to the prestigious Institut de France, succeeding Gaston La Touche in the Académie des Beaux-Arts, a testament to his esteemed position in the French art establishment. His works were acquired by major French museums, including the Musée du Luxembourg (the precursor to the Musée National d'Art Moderne) and numerous provincial museums.

Despite his success in Paris, Martin increasingly preferred the tranquility of Marquayrol. He continued to paint prolifically, drawing inspiration from his immediate surroundings. His later works maintain the high quality and distinctive style he had developed, characterized by a vibrant palette, shimmering light, and a deep sense of harmony with nature. Henri Martin passed away on November 12, 1943, in Labastide-du-Vert, the place that had become his spiritual and artistic home. He is buried in the cemetery there.

Legacy and Conclusion

Henri Martin's legacy is that of an artist who successfully navigated the complex artistic currents of his time, forging a distinctive personal style. He skillfully blended the technical innovations of Impressionism and Divisionism with the poetic and spiritual aspirations of Symbolism, creating works that are both visually captivating and emotionally resonant. His dedication to capturing the effects of light, particularly the warm, enveloping light of Southern France, resulted in paintings of enduring beauty.

While perhaps not as revolutionary as some of his contemporaries like Monet or Van Gogh, Martin's contribution to French art is significant. His large-scale decorative murals grace important public buildings, and his easel paintings are held in numerous museum collections, including the Musée d'Orsay in Paris, the Musée des Augustins in Toulouse, and the Musée de Cahors Henri-Martin, which is dedicated to his work and that of other artists from the Quercy region.

Henri Martin's art offers a vision of idyllic beauty, rural tranquility, and timeless contemplation. In a period marked by rapid social and artistic change, his work stands as a testament to the enduring power of light, color, and poetic idealism. He remains a beloved figure in French art, an artist who found his voice in the harmonious interplay of modern technique and a deeply personal, almost spiritual connection to the world around him. His paintings continue to enchant viewers with their luminous surfaces and serene, dreamlike atmospheres, securing his place as a master of light and poetic sensibility.