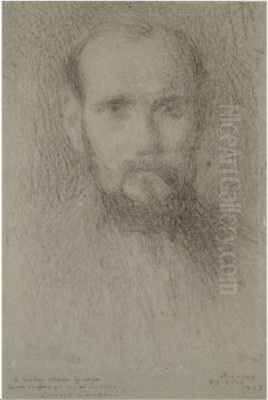

Ernest Joseph Laurent stands as a fascinating, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the vibrant tapestry of late 19th and early 20th-century French art. Born on June 8, 1859, in Gentilly, a suburb of Paris, and passing away in Bièvre on June 25, 1929, Laurent's artistic journey navigated the currents of Neo-Impressionism and Symbolism, forging a unique path characterized by technical finesse, spiritual depth, and a profound sensitivity to the intimate moments of life. His work, though rooted in the scientific inquiries of his Neo-Impressionist colleagues, ultimately sought a more personal and emotive expression, making him a bridge between objective observation and subjective experience.

Early Formation and Academic Pursuits

Laurent's artistic inclinations led him to the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, the bastion of academic art training in France. Here, he studied under Ernest Hébert, a painter known for his elegant portraits and romanticized genre scenes, often with Italianate themes. Hébert's influence, particularly his refined technique and emphasis on graceful composition, would leave a lasting mark on Laurent, even as the younger artist explored more avant-garde directions.

During his time at the École, Laurent formed crucial friendships that would shape his artistic development. Most notable among these was his bond with Georges Seurat, the pioneering figure of Neo-Impressionism, and Edmond Aman-Jean, who would become a distinguished Symbolist painter. The trio often spent time together, visiting the Louvre to study the Old Masters, discussing artistic theories, and undoubtedly debating the future of painting. This period was one of intense learning and camaraderie, laying the groundwork for their distinct yet interconnected careers. The academic environment, while traditional, provided Laurent with a strong foundation in drawing and composition, skills that would underpin his later, more experimental work.

The competitive spirit of the École was embodied in the Prix de Rome, a highly coveted scholarship that allowed promising artists to study at the French Academy in Rome. Laurent proved his mettle by winning the second prize in this competition in both 1889 and 1890. This achievement was a significant recognition of his talent and dedication within the academic system.

The Roman Sojourn and the Assisi Revelation

Following his success in the Prix de Rome, Laurent traveled to Italy in 1890. He spent time in Rome, where he served as an assistant to his former mentor, Ernest Hébert, who was then the director of the French Academy at the Villa Medici. This experience undoubtedly deepened his appreciation for classical art and the Italian landscape, themes that had already been part of Hébert's oeuvre. Rome, with its layers of history and artistic grandeur, offered a rich environment for any young artist.

However, it was a subsequent journey to Assisi, the birthplace of Saint Francis, that proved to be a profound turning point in Laurent's life and art. In this Umbrian hill town, steeped in spirituality and Franciscan history, Laurent underwent a significant mystical or religious experience. While the precise details of this experience remain personal, its impact on his artistic vision was undeniable. This encounter with a deeper spiritual reality shifted his focus. His art, which had been aligning with the more materialistic and observational concerns of Impressionism and early Neo-Impressionism, began to incorporate more overt religious themes and a palpable sense of symbolic meaning.

This spiritual awakening in Assisi imbued Laurent's subsequent work with a new layer of introspection and emotional resonance. He returned to Paris with a transformed perspective, seeking to convey not just the visible world, but the unseen spiritual and emotional currents that lie beneath its surface. This personal transformation set him on a path that, while still utilizing modern techniques, aimed for a more profound and contemplative art.

Embracing Neo-Impressionism

Before and concurrent with his spiritual evolution, Ernest Laurent was deeply engaged with the technical innovations of his time, particularly Neo-Impressionism. Spearheaded by his friend Georges Seurat, and further developed by artists like Paul Signac and Henri-Edmond Cross, Neo-Impressionism, also known as Pointillism or Divisionism, was a systematic and scientific approach to painting. It was a reaction against the perceived spontaneity and subjectivity of Impressionism, as practiced by artists like Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and Camille Pissarro.

Neo-Impressionists based their technique on contemporary optical theories, particularly the work of scientists like Michel Eugène Chevreul and Ogden Rood. They believed that by applying small, distinct dots or dabs of pure color to the canvas, these colors would mix optically in the viewer's eye, creating more vibrant and luminous effects than could be achieved by mixing pigments on a palette. Seurat's masterpieces, such as A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte (1884-1886), exemplified this meticulous, almost mosaic-like application of color, aiming for harmony, order, and a timeless quality.

Laurent adopted the Neo-Impressionist technique, drawn to its capacity for creating subtle atmospheric effects and a shimmering surface quality. His application of color, however, often tended towards a softer, more blended feel than the starker juxtapositions seen in some of Seurat's or Signac's works. He was less dogmatic in his adherence to strict Divisionist principles, allowing his personal sensibility to modulate the scientific rigor of the method. This flexibility would enable him to integrate Neo-Impressionist light and color with the more subjective and emotive aims of Symbolism.

The Allure of Symbolism

Parallel to the rise of Neo-Impressionism, the late 19th century also witnessed the flourishing of Symbolism, an artistic and literary movement that reacted against the perceived limitations of Realism and Naturalism. Symbolist artists, such as Gustave Moreau, Odilon Redon, and Puvis de Chavannes, sought to express ideas, emotions, and spiritual truths rather than merely depicting the objective, visible world. They favored suggestion over direct statement, dreams over reality, and the inner world of the imagination over external appearances.

The Symbolist ethos resonated deeply with Laurent, particularly after his transformative experience in Assisi. He found in Symbolism a means to explore the spiritual and psychological dimensions that had become central to his artistic concerns. His paintings began to feature figures imbued with a quiet melancholy or contemplative grace, often set in dreamlike or evocative atmospheres. While he continued to employ Neo-Impressionist techniques for their luminous qualities, the mood and content of his work increasingly aligned with Symbolist ideals. Artists like Fernand Khnopff in Belgium or Arnold Böcklin in Switzerland were exploring similar terrains of myth, dream, and psychological states, reflecting a broader European cultural shift towards introspection.

Laurent's brand of Symbolism was often subtle and intimate. He didn't typically engage in the grand mythological or allegorical narratives of some Symbolists. Instead, he found symbolic resonance in quiet domestic scenes, portraits of women lost in thought, and landscapes imbued with a sense of mystery or spiritual presence. His work shared affinities with the "Intimist" painters, such as Pierre Bonnard and Édouard Vuillard (both associated with the Nabis group, which itself had strong Symbolist roots), who focused on the poetry of everyday life and interior spaces, though Laurent's approach was often more overtly spiritual.

A Unique Synthesis: Laurent's Artistic Signature

Ernest Joseph Laurent's mature style is characterized by this unique synthesis of Neo-Impressionist technique and Symbolist sensibility. He masterfully used the dotted brushwork of Neo-Impressionism to create surfaces that shimmer with light and subtle color harmonies. Yet, this technique was not an end in itself but a means to evoke a particular mood—often one of quiet contemplation, gentle melancholy, or spiritual serenity.

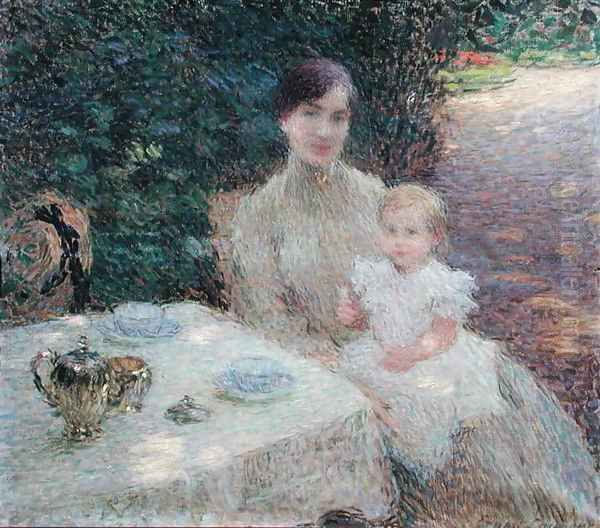

His subject matter frequently revolved around female figures, often depicted in domestic interiors, gardens, or softly lit landscapes. These women are rarely active; instead, they are pensive, absorbed in their thoughts or gentle activities, embodying a sense of inner life and quietude. Laurent had a particular gift for capturing a sense of vulnerability and delicate grace. His palette, while capable of Neo-Impressionist vibrancy, often favored softer, more muted tones, creating an atmosphere of dreamlike intimacy.

This blending of styles can be seen as a reflection of Laurent's own temperament—an artist who valued both the intellectual rigor of scientific color theory and the intuitive, emotional depth of spiritual experience. He sought a harmony between the external world of appearances, rendered with sophisticated technique, and the internal world of feeling and spirit. This distinguished him from more purely scientific Neo-Impressionists and from Symbolists who might have eschewed such structured techniques. He found a middle ground, a personal language that allowed him to express complex, nuanced states of being.

Representative Works and Thematic Concerns

Several works exemplify Laurent's artistic vision. His lithographs, such as October Evening (Soir d'Octobre), created around 1897-1898, showcase his ability to translate the luminous qualities of his paintings into the print medium. These works often depict solitary female figures in crepuscular settings, the fading light rendered through delicate stippling, evoking a mood of quiet reflection and the gentle melancholy of autumn. The choice of evening or twilight settings is characteristic, as these liminal times of day lend themselves to introspection and a sense of mystery.

His oil paintings, such as Nu avec fleurs (Nude with Flowers) from around 1910, demonstrate his skill in rendering the human form with a soft, ethereal quality, bathed in a gentle, diffused light. The flowers, often a recurring motif, can be seen as symbols of beauty, transience, or the natural world's quiet poetry. Another notable work is his portrait of the composer Charles de Tournemire, a fellow artist with strong Catholic faith, which fetched a significant price at auction, indicating the recognized quality of his portraiture.

Religious themes, inspired by his Assisi experience, also found their way into his art, though often expressed with a gentle reverence rather than overt dogmatism. These works might depict scenes from the lives of saints or moments of spiritual contemplation, always rendered with his characteristic sensitivity and refined technique. He was less concerned with grand theological statements and more with conveying a personal sense_of faith and the sacredness inherent in quiet moments.

Laurent and His Contemporaries: Connections and Distinctions

Laurent's position within the art world of his time was complex. He maintained friendships with key figures from different artistic camps. His early association with Georges Seurat placed him at the heart of Neo-Impressionism. However, Seurat's untimely death in 1891 marked a significant loss for the movement and for Laurent personally. While Seurat was rigorously scientific, almost architectural in his compositions, Laurent's Neo-Impressionism became softer, more atmospheric, and increasingly infused with subjective emotion.

His friendship with Edmond Aman-Jean, a dedicated Symbolist, provided another important artistic dialogue. Aman-Jean's work, often featuring ethereal female figures and decorative compositions, shared some common ground with Laurent's later interests, though Aman-Jean's style was generally more fluid and less reliant on the systematic application of color.

Laurent also had connections with other artists who navigated similar paths between Neo-Impressionism and Symbolism, or who developed a more poetic, "Intimist" form of Post-Impressionism. Henri Le Sidaner, for instance, was a close friend, and his paintings of quiet, lamplit gardens and empty tables share a similar mood of gentle melancholy and evocative atmosphere with Laurent's work, though Le Sidaner's technique was more Impressionistic. Henri Martin was another contemporary who successfully blended Neo-Impressionist techniques with Symbolist themes, often on a larger, decorative scale for public murals, depicting idyllic, timeless scenes.

Compared to the more radical Post-Impressionists like Vincent van Gogh, with his passionate, expressive brushwork, or Paul Gauguin, with his bold Primitivism and Synthetist style, Laurent's art appears more restrained and traditional in its pursuit of harmony and beauty. Yet, within his chosen parameters, he achieved a remarkable depth and sincerity. He was not an artistic revolutionary in the mold of Pablo Picasso or Henri Matisse, who were beginning to forge Cubism and Fauvism in the early 20th century, but rather a quiet innovator who synthesized existing trends into a deeply personal and refined artistic language.

Later Career and Legacy

Throughout his career, Ernest Joseph Laurent continued to exhibit his work, gaining respect for his technical skill and the unique sensibility of his paintings and prints. He became a member of the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts and later a professor at the École des Beaux-Arts, passing on his knowledge to a new generation of artists. His dedication to his craft and his consistent artistic vision earned him a respected place in the French art establishment.

While perhaps not as widely known today as some of his more revolutionary contemporaries, Laurent's contribution is significant. He represents a particular strand of Post-Impressionism that sought to reconcile modern techniques with a desire for spiritual expression and intimate beauty. His work demonstrates that the scientific principles of Neo-Impressionism could be adapted to serve more poetic and subjective ends. He showed how an artist could be deeply influenced by the avant-garde currents of his time yet forge a path that was uniquely his own, guided by personal experience and a profound inner life.

His paintings and prints remain as testaments to a gentle, contemplative spirit, offering a quiet counterpoint to the more tumultuous artistic developments of the early 20th century. They invite viewers into a world of subtle light, delicate emotion, and serene beauty, reflecting an artist who found profundity in the quiet corners of life and the enduring power of the human spirit. Ernest Joseph Laurent's art continues to resonate with those who appreciate technical mastery combined with heartfelt sensitivity and a touch of the ethereal. His legacy lies in this delicate balance, a quiet voice that still speaks eloquently of the search for beauty and meaning in a rapidly changing world.