Henry Moore stands as a colossus in the annals of 20th-century art. A British sculptor and artist, his life spanned a period of immense global change, from his birth on July 30, 1898, to his death on August 31, 1986. Moore's work, primarily known through his semi-abstract monumental bronze sculptures, reshaped the landscape of modern sculpture, forging a unique path that blended humanism, abstraction, and a profound connection to the natural world. His influence extended far beyond the British Isles, making him one of the most recognized and celebrated artists of his time.

His journey from the son of a coal miner in Yorkshire to an internationally acclaimed figure is a testament to his singular vision and relentless dedication. Moore's art explored enduring themes, most notably the reclining figure and the mother and child, finding in them universal resonance. He navigated the currents of modernism, drawing inspiration from diverse sources while developing a deeply personal and instantly recognizable style.

Early Life and Formative Years

Henry Spencer Moore was born in Castleford, a small mining town in West Yorkshire, England. He was the seventh of eight children born to Raymond Spencer Moore and Mary Baker. His father, a mining engineer who rose from pitman, was determined that his sons would not follow him into the mines. He saw education as the path to advancement, a value that shaped Henry's early life, although not entirely as his father envisioned.

Moore's interest in sculpture emerged early, reportedly sparked by hearing of Michelangelo's achievements at Sunday school around the age of eleven. He began modeling in clay and carving wood, encouraged by a teacher, Alice Gostick. Despite this burgeoning passion, his father initially steered him towards a teaching career. Moore became a student-teacher at Castleford Secondary School, the same school he had attended.

His path took a dramatic turn with the outbreak of World War I. In 1917, at the age of eighteen, Moore volunteered for army service with the Civil Service Rifles Regiment. He saw action in France at the Battle of Cambrai but his combat experience was cut short when he was injured in a gas attack in November 1917. After recovering in hospital, he spent the remainder of the war as a physical training instructor. This wartime experience, including the exposure to poison gas, would subtly inform his later work, particularly themes of vulnerability and resilience.

Following demobilization in 1919, Moore seized the opportunity provided by an ex-serviceman's grant to pursue his artistic ambitions. He enrolled at the Leeds School of Art, becoming their first student dedicated solely to sculpture. It was here that his formal training began, laying the groundwork for his future career and introducing him to fellow student Barbara Hepworth, who would become another leading figure in British modern sculpture.

The Emergence of a Style

After two years in Leeds, Moore won a scholarship to the prestigious Royal College of Art (RCA) in London in 1921. London opened up a world of artistic possibilities. He frequented the British Museum, particularly its ethnographic collections, where he encountered the power and formal invention of non-Western art. African, Egyptian, Oceanic, and particularly Pre-Columbian Mexican sculpture left an indelible mark on his developing aesthetic. He was especially drawn to a plaster cast of the Toltec-Maya Chacmool figure, a reclining form whose monumental presence and formal austerity deeply impressed him.

These influences offered a potent alternative to the classical Greek and Renaissance traditions that still dominated academic sculpture. Moore embraced the principle of "truth to materials," believing that the sculptor should respect the inherent qualities of the stone or wood being worked. He also championed "direct carving," working straight into the material rather than relying solely on preparatory models, a practice advocated by contemporaries like Constantin Brancusi and Jacob Epstein, the latter already a controversial modern force in London.

In 1924, upon completing his diploma, Moore accepted a seven-year teaching post at the RCA. This period was crucial for his development. Travel scholarships allowed him to visit Italy, where he admired the frescoes of Giotto and Masaccio, and Paris, where he encountered the work of the European avant-garde, including Pablo Picasso and the Cubists. While impressed by their innovations, Moore sought his own path, synthesizing these modern influences with his deep interest in ancient and non-Western art. His early works often featured reclining female figures and mother-and-child groups, themes that would remain central throughout his career.

Developing Themes and Recognition

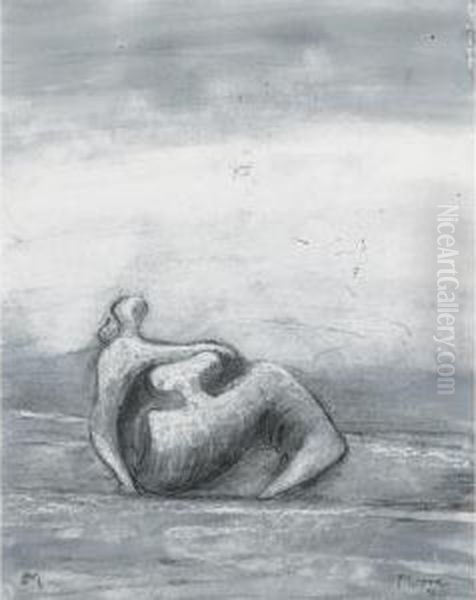

Throughout the late 1920s and 1930s, Moore's distinctive style began to solidify. His reclining figures became increasingly abstract, their forms echoing the undulations of hills and landscapes. He explored the relationship between solid form and empty space, introducing holes and openings into his sculptures. These voids were not mere absences but active components of the composition, integrating the surrounding space and enhancing the work's three-dimensionality. This concept of interpenetration between internal and external forms became a hallmark of his work.

His exploration of the mother-and-child theme also evolved. These works ranged from tender depictions to more primal, abstracted forms, often emphasizing the protective embrace of the mother. Moore saw these themes as archetypal, rooted in fundamental human experiences and the natural world. He drew inspiration from the shapes of pebbles, bones, and shells found near his home, seeing in them the essential forms of life.

During this time, Moore became associated with a group of progressive artists based in Hampstead, London, which included Barbara Hepworth, her husband Ben Nicholson, the painter Paul Nash, and the critic Herbert Read. They were key figures in the Unit One group, formed in 1933 to promote modern art and design in Britain. Moore also exhibited with the Surrealists, though he never fully subscribed to their ideology, his work remaining grounded in observation of the human form and nature, albeit abstracted. His connections extended to European artists like Jean Arp and Alberto Giacometti, whose biomorphic forms and explorations of the human figure resonated with his own concerns.

Despite growing recognition within avant-garde circles, Moore's work often met with resistance from the more conservative elements of the British art establishment and public. A 1931 exhibition at the Leicester Galleries provoked hostile press reviews, with one critic famously decrying his work as "immoral" and "bolshevik." This controversy even led to calls for his resignation from the Royal College of Art, highlighting the challenging path modern artists faced in gaining acceptance.

The War Years and Shelter Drawings

The outbreak of World War II in 1939 profoundly impacted Moore's life and art. His Hampstead home was damaged by bombing, prompting a move to Perry Green, a hamlet in rural Hertfordshire, where he would live and work for the rest of his life. Unable to continue large-scale sculpting due to wartime restrictions, Moore accepted a commission from the War Artists' Advisory Committee (WAAC), headed by Kenneth Clark.

His task was to document life on the home front. Moore turned his attention to the London Underground stations, where thousands of Londoners sought nightly refuge from the Blitz. Between the autumn of 1940 and the summer of 1941, he produced a remarkable series of drawings known as the "Shelter Drawings." Using wax crayons, watercolour, pen and ink, he depicted rows of sleeping figures huddled on the platforms, wrapped in blankets, their forms suggesting both individual vulnerability and collective endurance.

These drawings were a departure from his pre-war sculptural work but shared its underlying humanism. The figures, often simplified and monumental despite their small scale, conveyed a sense of quiet dignity and resilience in the face of adversity. They resonated deeply with the public and critics alike, bringing Moore's work to a much wider audience and cementing his reputation as a major British artist. The drawings captured the stoicism and shared experience of wartime London, transforming the underground tunnels into modern catacombs filled with sleeping humanity. He also undertook another WAAC commission depicting coal miners at the Wheldale Colliery in Yorkshire, where his father had worked, connecting his art back to his origins.

Post-War Ascendancy and Public Commissions

The end of the war marked the beginning of Henry Moore's international fame. A major retrospective exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York in 1946 introduced his work to an American audience to great acclaim. Two years later, in 1948, he won the International Sculpture Prize at the Venice Biennale, confirming his status as a leading figure in contemporary art.

This period saw Moore increasingly working on a monumental scale, often in bronze. While he had previously championed direct carving, the demands of large public commissions and the desire for multiple editions led him to embrace modeling in plaster or clay for casting. His studio at Perry Green expanded, employing assistants to help with the casting process, though Moore always retained final control over the patination and finish.

One of the most significant commissions of the immediate post-war era was the Madonna and Child (1943-44) for St Matthew's Church in Northampton. Carved in Hornton stone, this work blended Moore's characteristic formal simplification with a sense of serene dignity appropriate for its ecclesiastical setting. Despite its eventual acceptance, the sculpture initially caused controversy within the local community, reflecting the ongoing public debate surrounding modern religious art.

Numerous other prestigious commissions followed. He created large reclining figures for the Festival of Britain (1951), the UNESCO headquarters in Paris (1957-58, carved from travertine marble), and the Lincoln Center in New York (1963-65). Other notable public works include Knife Edge Two Piece (1962-65) sited near the Houses of Parliament in London, and Nuclear Energy (1964-66) commemorating the first self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction at the University of Chicago. These large-scale works, often sited outdoors, fulfilled Moore's long-held belief that sculpture achieved its full potential in relation to architecture or landscape.

Exploring Core Themes: Reclining Figures and Motherhood

Throughout his long career, Moore continually returned to and reinterpreted his core themes. The reclining figure remained his most persistent subject, evolving through numerous variations in stone, wood, and bronze. For Moore, the reclining pose offered immense formal possibilities, allowing him to explore the human body as a landscape, echoing the forms of hills, valleys, and caves. He saw it as a pose suggesting repose, endurance, and a connection to the earth.

His reclining figures range from relatively naturalistic representations to highly abstracted forms where limbs merge and dissolve into organic masses. The introduction of holes and voids became particularly significant in these works, creating a dynamic interplay between solid and space, mass and lightness. These openings often frame views of the surrounding landscape, integrating the sculpture with its environment in a way that was revolutionary for its time.

The mother-and-child theme also remained a constant source of inspiration. Moore explored the emotional and physical bond between mother and child, often emphasizing the protective, nurturing aspect of the relationship. Some works convey tenderness and intimacy, while others possess a more primal, archetypal power. The Northampton Madonna is a key example of his ability to infuse this theme with spiritual resonance. In later years, he created numerous variations, including family group sculptures, broadening the theme to encompass wider human connections.

Other recurring motifs include his "Helmet Head" series, often linked to his wartime experiences and exploring themes of protection, aggression, and the relationship between internal and external forms. He also produced numerous drawings and prints, exploring ideas and forms often related to his sculptural projects. His graphic work, particularly the Shelter Drawings and Coal Miner series, stands as a significant achievement in its own right.

Materials, Techniques, and the Studio

Moore's approach to materials evolved over his career. His early adherence to "truth to materials" and direct carving was deeply influenced by his study of ancient and non-Western art, as well as the ideas of contemporaries like Brancusi and sculptors associated with the Arts and Crafts movement. He valued the unique character of different stones (like Hornton, Cumberland Alabaster, Verde di Prato) and woods (elm, beech), allowing the material's grain or texture to inform the final shape.

However, the demands of large-scale commissions and the desire to create multiple versions of a work led him increasingly towards modeling and casting, particularly in bronze. He would typically create a plaster maquette, scale it up, refine the full-size plaster model, and then send it to a foundry for casting using the lost-wax process. Moore became highly skilled in overseeing the patination of his bronzes, using acids and heat to achieve a wide range of colours and surface textures that enhanced the form and character of each piece.

His studio complex at Perry Green grew significantly over the years to accommodate his prolific output and the scale of his projects. He employed a team of assistants who helped with the physically demanding aspects of enlarging maquettes, creating plaster models, and finishing bronzes. Despite this delegation, Moore remained intimately involved in every stage of the creative process, ensuring each work reflected his artistic vision. The landscape around his studios became an outdoor gallery for his monumental sculptures, demonstrating his belief in the synergy between art and nature.

Relationships, Rivalries, and Context

Henry Moore did not work in isolation. His career unfolded within the dynamic context of 20th-century modernism, marked by interactions, collaborations, and rivalries with fellow artists. His relationship with Barbara Hepworth was particularly significant. They were fellow students at Leeds and the RCA, shared studios in Hampstead, and were both central figures in the development of modern British sculpture. Their friendship was intertwined with a degree of professional rivalry, as they explored similar themes and materials, albeit with distinct sensibilities – Moore's forms often more grounded and biomorphic, Hepworth's perhaps more purely abstract and refined.

His association with Ben Nicholson, Paul Nash, Herbert Read, and others in the Unit One group placed him at the forefront of the British avant-garde in the 1930s. He engaged with Surrealism, exhibiting with the group, and absorbing aspects of its interest in the subconscious and unexpected juxtapositions, evident in works like his Helmet Heads. He admired Picasso's relentless innovation and Epstein's powerful expressionism.

Moore's international success after WWII placed him in dialogue with global figures like Alberto Giacometti, whose existential explorations of the human figure offered a different, though equally compelling, vision. While Moore's work retained a connection to organic forms and humanism, he was aware of subsequent developments, including the rise of Abstract Expressionism in painting and new directions in sculpture.

His established position inevitably drew reactions from younger generations. The "Geometry of Fear" sculptors – Lynn Chadwick, Reg Butler, Kenneth Armitage, Bernard Meadows – who gained prominence at the 1952 Venice Biennale, presented a starker, more angular, and arguably more anxious vision of the post-war world, contrasting with Moore's perceived organicism and stability. Later, some critics and artists associated with Pop Art or Minimalism viewed Moore's work as belonging to an older, more traditional humanistic vein of modernism.

He also collaborated across disciplines, notably creating lithographs for a collection of poems by W.H. Auden, La Poésie, published by the Swiss gallery owner and publisher Gerald Cramer, with whom Moore maintained a long working relationship for his graphic works. These interactions highlight Moore's engagement with the broader cultural landscape of his time.

Controversies and Critical Reception

From early in his career, Henry Moore's work challenged conventional tastes and provoked debate. The initial hostility towards his abstracted forms, particularly the perceived "distortions" of the human body, was common for many modernist pioneers. The negative press reaction to his 1931 Leicester Galleries show, accusing his work of being ugly and subversive, exemplifies the resistance he faced. This incident reportedly led to pressure behind the scenes for him to leave his teaching post at the RCA, though he moved to the Chelsea School of Art shortly thereafter.

Even works that later became beloved icons, like the Northampton Madonna, faced initial opposition. Some members of the congregation found its modern style inappropriate for a church setting, leading to local controversy. This highlights the gap that often existed between avant-garde artistic expression and public understanding, particularly concerning religious or commemorative art.

As Moore achieved global fame and became synonymous with British modern art, a different kind of critique emerged. Some younger artists and critics began to view him as an "establishment" figure, his work ubiquitous in corporate plazas and public institutions. His very success led to accusations that his art had become safe, predictable, or overly monumental. The challenge posed by the "Geometry of Fear" sculptors at the 1952 Biennale was partly framed as a reaction against Moore's perceived dominance and style.

Furthermore, Moore's commitment to humanistic themes and organic forms sometimes seemed out of step with later, more conceptual or radically abstract art movements. His socialist political leanings, formed early in life, and his engagement with social themes (like the Shelter Drawings) were sometimes contrasted with the perceived apolitical nature of later art trends. Despite these critiques, his work continued to command respect and influence, demonstrating the enduring power of his vision.

Later Life and Enduring Legacy

Henry Moore remained remarkably productive throughout his later years, continuing to create monumental sculptures, drawings, and prints well into his eighties. His international reputation solidified, with major exhibitions and retrospectives held worldwide. He received numerous honours, including the Companion of Honour (1955) and the Order of Merit (1963) – rejecting a knighthood as he felt it would distance him from ordinary people.

A significant aspect of his later life was the establishment of the Henry Moore Foundation in 1977. Concerned with securing his artistic legacy and supporting the future of sculpture, Moore gifted the bulk of his estate, including artworks and the Perry Green property, to the Foundation. Its mission is to encourage public appreciation of the visual arts, particularly sculpture, through exhibitions, research, and grants. The Foundation continues to operate from his former home and studios, preserving his working environment and making his art accessible to scholars and the public.

Moore's influence on subsequent generations of sculptors is undeniable. His exploration of form and space, his integration of sculpture with landscape, and his commitment to public art opened up new possibilities. Artists like Anthony Gormley, with his focus on the human form in relation to space and environment, and Anish Kapoor, known for his monumental abstract works exploring voids and reflective surfaces, can be seen as engaging with aspects of Moore's legacy.

His work is held in virtually every major modern art museum globally, from the Tate in London to MoMA in New York and the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto, which holds a significant collection. His monumental sculptures continue to define public spaces worldwide, testament to his belief in art's civic role. He fundamentally changed the course of British sculpture and remains a pivotal figure in the narrative of 20th-century art.

Conclusion: A Humanist Vision in Form

Henry Moore's contribution to modern art is immense. He navigated the complex currents of the 20th century, responding to its traumas and triumphs through a deeply personal yet universally resonant artistic language. His sculptures, whether intimate carvings or monumental bronzes, speak of the enduring relationship between humanity and nature, the resilience of the human spirit, and the fundamental experiences of life, birth, and protection.

By synthesizing influences from ancient civilizations, non-Western cultures, and the European avant-garde, Moore forged a unique style characterized by organic abstraction, the dynamic use of space, and profound humanism. His commitment to public art ensured his work reached beyond gallery walls, becoming part of the lived environment for millions. Through his art and the foundation bearing his name, Henry Moore's exploration of form and the human condition continues to inspire and provoke, securing his place as one of the most important sculptors of his era.