It is important to clarify from the outset a potential point of confusion. While research might occasionally surface mentions of a "Joaquin Miro (1849-1914)," perhaps associated with minor works like a watercolor titled "Market Stall on the Square in Marseille," this appears to be a case of mistaken identity or conflated information. The towering figure in 20th-century art known internationally is Joan Miró i Ferrà, a Spanish artist born in Barcelona in 1893, who lived a long and profoundly influential life until his passing in Palma de Mallorca in 1983. This article focuses on this celebrated Joan Miró, a master whose work traversed painting, sculpture, ceramics, and printmaking, leaving an indelible mark on Surrealism and abstraction.

Miró stands as one of the most original and beloved artists of the modern era. His visual language, characterized by biomorphic forms, geometric shapes, and a vibrant palette, created a universe brimming with poetic symbolism, childlike wonder, and profound connections to the subconscious and the natural world. He navigated the turbulent artistic currents of the early 20th century, engaging with Cubism, Fauvism, and Dadaism, before forging a unique path closely associated with Surrealism, though he always maintained a fierce independence from rigid doctrines. His legacy is not just in his iconic artworks but also in his innovative spirit and his relentless exploration of materials and forms.

Formative Years in Catalonia

Joan Miró i Ferrà was born on April 20, 1893, in the bustling port city of Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain. His father, Miquel Miró Adzerias, was a watchmaker and goldsmith, while his mother, Dolors Ferrà i Oromí, came from a family of cabinetmakers in Mallorca. This background, blending meticulous craft with artistry, perhaps subtly influenced the precision and imaginative construction found in his later work. Although his family initially encouraged him towards a more practical career in business, Miró's artistic inclinations were evident from a young age.

He began drawing classes at the age of seven. After a brief and unhappy stint as a clerk, a bout of typhoid fever and a subsequent period of convalescence at his family's farm in Mont-roig del Camp proved pivotal. The rural Catalan landscape – its earth, sky, plants, and creatures – became a deep and enduring source of inspiration, a touchstone he would return to throughout his career. This connection to the specific soil and culture of Catalonia remained a fundamental aspect of his identity and art.

Persuading his family of his true calling, Miró enrolled at Francesc Galí's Escola d'Art in Barcelona in 1912. Galí was an unconventional teacher who encouraged his students to develop their sense of touch and spatial awareness, even having them draw objects blindfolded. This period was crucial for Miró's development, exposing him to contemporary European art movements through exhibitions and publications. He absorbed influences from the bold colors of Fauvism, particularly artists like Henri Matisse, and the fragmented forms of Cubism, pioneered by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque. He also studied life drawing at the Cercle Artístic de Sant Lluc.

His early works from this period show a young artist grappling with these powerful influences. Paintings reveal an interest in vibrant, non-naturalistic color and experiments with flattened perspectives and geometric simplification. He was also deeply impressed by the power and directness of Catalan Romanesque frescoes and folk art, elements whose simplicity and symbolic force would resonate in his mature style. These formative years in Barcelona laid the essential groundwork, technically and thematically, for the revolutionary art he would later create.

Parisian Encounters and Artistic Awakening

The allure of Paris, the undisputed center of the art world in the early 20th century, proved irresistible for the ambitious young Miró. He made his first trip in 1920, a move that would fundamentally alter the course of his artistic journey. Armed with introductions, including one to his fellow Spaniard Pablo Picasso, Miró began to immerse himself in the city's vibrant avant-garde milieu. Picasso, already an established figure, offered encouragement and support to his younger compatriot.

Life in Paris was initially challenging. Miró lived in poverty, often working in cramped studios, but the creative energy of the city was intoxicating. He frequented galleries, museums, and cafes where artists and writers congregated, absorbing new ideas and forging important connections. He became associated with the circle of poets and writers around figures like Pierre Reverdy, Tristan Tzara (a key figure in Dadaism), and later, André Breton, the future leader of the Surrealist movement.

This immersion in the Parisian avant-garde accelerated Miró's departure from his earlier, more representational styles influenced by Fauvism and Cubism. While those movements provided essential lessons in color and form, Miró sought a more personal and poetic means of expression. The anti-rational, often playful, and provocative spirit of Dadaism resonated with his desire to break free from artistic conventions.

His paintings from the early 1920s reflect this transition. Works created just before or during his initial years in Paris still show debts to Cubism's structure, but a new kind of imaginative detail and personal symbolism begins to emerge. The meticulous observation honed during his time in Mont-roig started to blend with a more dreamlike, internal vision, paving the way for his groundbreaking works of the mid-1920s. The Parisian experience was not just about learning new techniques; it was about finding his unique voice amidst the chorus of modernism.

Inventing a Personal Surrealism

By the mid-1920s, Paris was buzzing with the emergence of Surrealism, formally launched by André Breton's Surrealist Manifesto in 1924. The movement championed the exploration of the subconscious mind, dreams, and automatic processes as sources of artistic creation, seeking to unlock a reality beyond rational control. Miró found himself naturally aligned with many of these ideas, particularly the emphasis on instinct, chance, and the poetic potential of the irrational.

Although he exhibited with the Surrealists and shared many of their core interests, Miró never officially joined the group or fully subscribed to Breton's often dogmatic leadership. He maintained his independence, preferring to cultivate his own highly personal form of Surrealism. He was particularly drawn to the concept of automatism – allowing the hand to move freely across the canvas without conscious control, tapping into subconscious impulses. This technique, also explored by artists like André Masson, became a crucial tool for Miró, helping him generate initial forms and compositions that he would later refine.

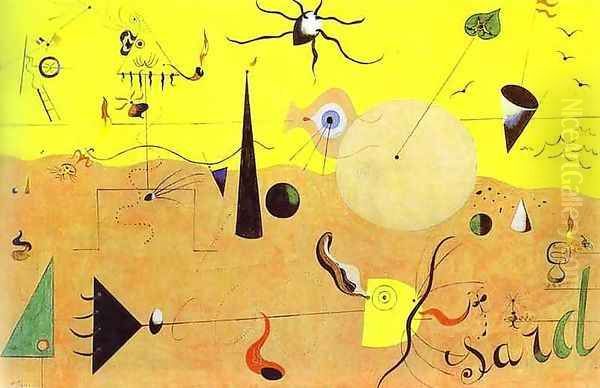

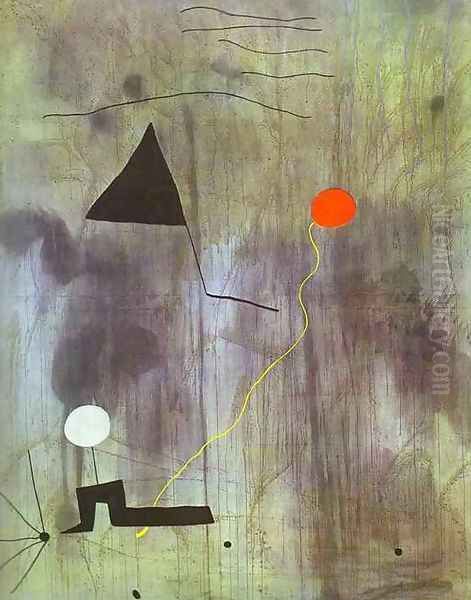

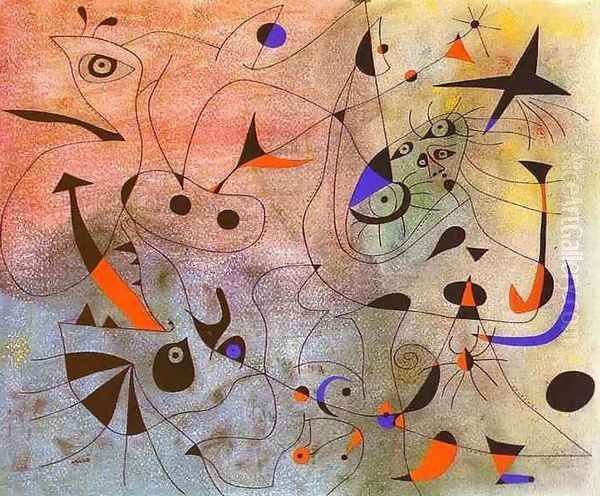

This period saw the creation of some of Miró's most celebrated and revolutionary works. He developed a unique sign language of biomorphic and geometric shapes floating in ambiguous, often brightly colored spaces. Stars, suns, eyes, insects, birds, and abstracted human figures populated his canvases, derived from his memories, dreams, and his deep connection to the Catalan landscape, but transformed into a universal poetic vocabulary.

His approach differed from the more illusionistic dreamscapes of Surrealists like Salvador Dalí or Yves Tanguy. Miró's work was flatter, more graphic, emphasizing line, color, and symbolic form over realistic depiction. He sought what he called a "reality more real than reality itself," a poetic truth accessed through intuition and imagination rather than logic. His engagement with Surrealism provided a fertile context, but ultimately, Miró forged his own distinct path, creating a visual world instantly recognizable as his own.

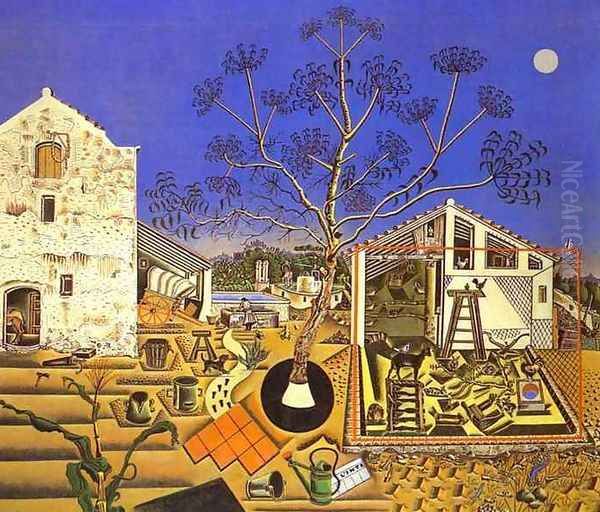

Iconic Canvases: The Farm and Harlequin's Carnival

Two paintings from the early 1920s stand out as seminal works marking Miró's transition and the emergence of his mature style: The Farm (1921-1922) and Harlequin's Carnival (1924-1925). The Farm is a detailed, almost encyclopedic depiction of his family's property in Mont-roig. Miró himself described it as "a summary of my entire life in the country." While rooted in observation, the painting transcends simple realism. Every element – the farmhouse, the animals, the plants, the tools – is rendered with meticulous, almost obsessive clarity, yet flattened and arranged with a logic that feels both descriptive and symbolic.

The painting combines sharp focus with a slightly distorted perspective, imbuing the familiar scene with a magical intensity. It represents a bridge between his earlier, more representational work and the imaginative freedom to come. Its creation was arduous, and Miró considered it a cornerstone of his oeuvre. Famously, the writer Ernest Hemingway purchased The Farm, recognizing its unique power and considering it one of his most prized possessions. It captured the essence of the Catalan landscape that was so fundamental to Miró's being.

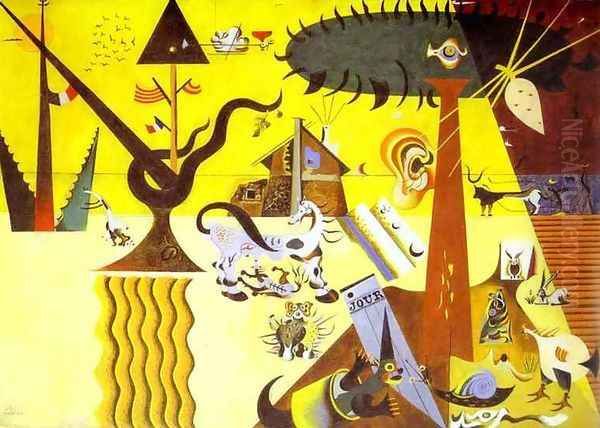

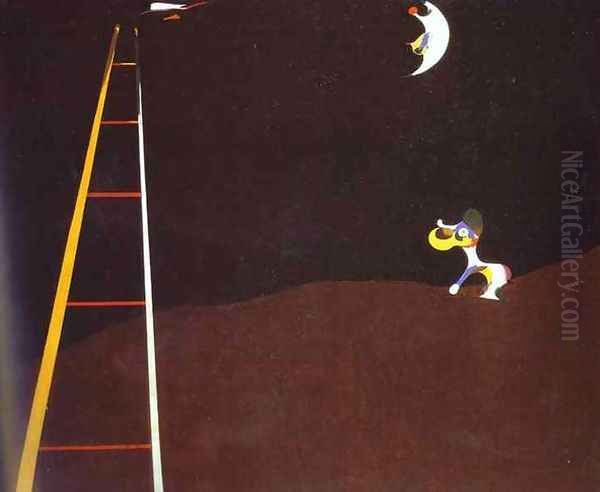

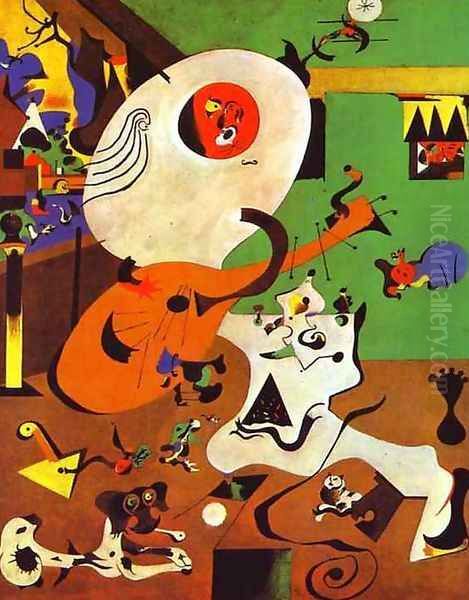

Harlequin's Carnival, painted just a few years later, represents a quantum leap into the realm of Surrealist fantasy. This vibrant, energetic canvas is considered one of the masterpieces of Miró's engagement with Surrealism. It depicts a fantastical gathering of bizarre, animated creatures and objects within a room. Biomorphic forms dance and float, musical notes escape from instruments, a ladder reaches towards a window, and geometric shapes interact in a playful, chaotic ballet.

The work is often interpreted as an expression of subconscious imagery, possibly fueled by the hunger-induced hallucinations Miró reportedly experienced during his impoverished years in Paris. It exemplifies his use of automatism, generating a spontaneous flow of imagery, which he then carefully composed. The painting is filled with personal symbols and a sense of joyous, albeit strange, celebration. Harlequin's Carnival perfectly encapsulates Miró's ability to blend humor, poetry, and the bizarre, establishing the foundations of the unique visual language that would define his career.

Art in Times of Conflict

The political and social upheavals of the 1930s and 1940s, particularly the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) and World War II (1939-1945), profoundly impacted Miró and his art. Though not overtly political in the manner of some contemporaries, his work during this period reflects the anxiety, violence, and uncertainty of the times. His style shifted, becoming more aggressive and expressive.

During the mid-1930s, leading up to and during the Spanish Civil War, Miró produced what are often called his "Savage Paintings." These works feature distorted, monstrous figures rendered with harsh lines and acidic colors. They convey a sense of anguish and brutality, a visceral reaction to the escalating tensions in Spain and Europe. The playful lyricism of earlier works gave way to a darker, more tormented vision, reflecting a world descending into chaos.

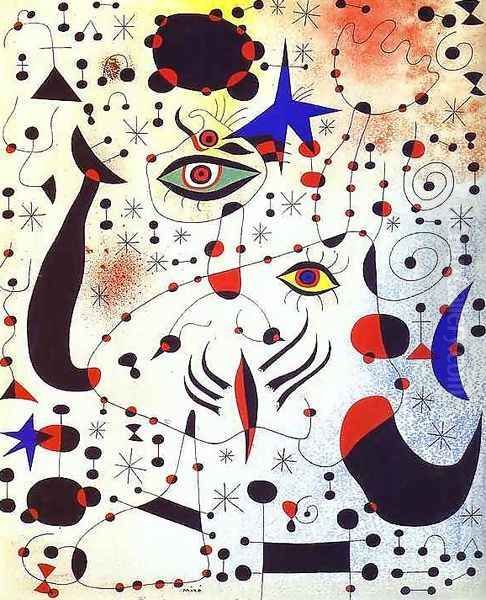

Forced into exile by the Spanish Civil War, Miró spent time in Paris and later sought refuge in Normandy as World War II began. During the early war years, living in relative isolation in Varengeville-sur-Mer, he created one of his most exquisite series: the Constellations (1940-1941). These 23 small works on paper are intricate compositions of delicate lines, dots, and his characteristic symbols (stars, moons, birds, figures) interconnected in complex networks against subtly washed backgrounds.

The Constellations represent a form of escape and poetic resistance amidst the surrounding darkness. They evoke a sense of cosmic harmony and intricate balance, a private universe created as a counterpoint to the external turmoil. Their small scale was partly dictated by circumstance, but it also lends them an intimate, jewel-like quality. After the war, Miró returned to Spain, settling first in Barcelona and later establishing a permanent home and studio in Palma de Mallorca in 1956. The experiences of conflict and exile left a lasting mark, adding layers of complexity and emotional depth to his subsequent work.

Beyond the Canvas: Sculpture, Ceramics, and Printmaking

While painting remained central to his practice, Joan Miró was a restless innovator who constantly explored the possibilities of different materials and media. His creative energy extended significantly into sculpture, ceramics, and printmaking, areas where he produced substantial and highly original bodies of work, often blurring the lines between these disciplines.

Miró began experimenting seriously with sculpture in the late 1920s and 1930s, creating object-assemblages that combined found items in poetic and unexpected ways, echoing Dadaist and Surrealist practices. Later, particularly from the 1940s onwards, he turned increasingly to bronze casting, though his approach remained unconventional. He often created initial forms from disparate found objects – pieces of metal, farm tools, stones, everyday items – which were then cast in bronze and frequently painted in bright, primary colors. These sculptures possess the same playful, totemic quality as his paintings, translating his biomorphic forms and symbolic figures into three dimensions. Works like The Ladder of Escape exist in both painted and sculptural forms, highlighting the fluidity between media in his mind.

His involvement with ceramics was equally significant, marked by a long and fruitful collaboration with the master ceramicist Josep Llorens Artigas, beginning in the 1940s. Together, they pushed the boundaries of the medium, creating highly expressive, often rugged and unconventional ceramic pieces, including vases, plaques, and large-scale murals. Miró treated the ceramic surface much like a canvas, applying glazes with painterly freedom and incorporating his characteristic motifs. Their collaborative murals, such as those for the UNESCO headquarters in Paris, are major achievements in public art.

Printmaking was another vital area of exploration throughout Miró's career. He became a master of etching and lithography, producing thousands of prints. He valued the collaborative nature of the print workshop and the potential for experimentation offered by different techniques. His prints often feature the same vibrant colors and symbolic language as his paintings, allowing his distinctive imagery to reach a wider audience. This multidisciplinary approach underscores Miró's holistic vision of art, where ideas flowed freely between different forms and materials. His friendship with Alexander Calder, known for his mobiles, might also reflect a shared interest in playful forms and spatial dynamics across different media.

Monumental Visions and Late Abstraction

In the later decades of his career, from the 1950s until his death in 1983, Miró's work often took on a larger scale and moved towards greater simplification and abstraction, while still retaining his unmistakable symbolic language. Having achieved international renown, he received numerous commissions for major public artworks, allowing him to realize long-held ambitions of integrating his art into architectural spaces.

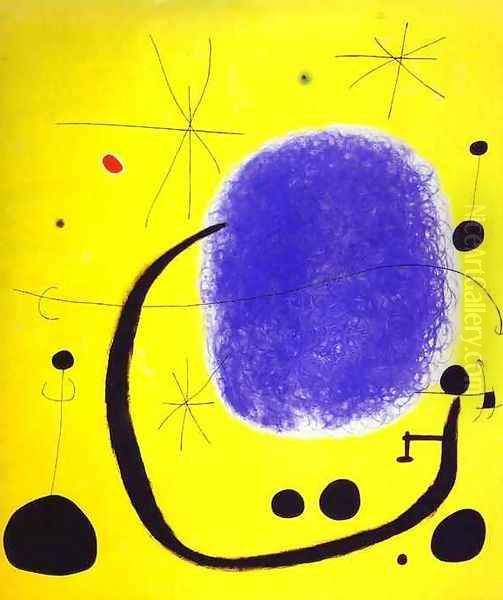

His studio in Palma de Mallorca, designed by his friend, the architect Josep Lluís Sert, provided him with the space and environment to work on these monumental projects. The famous Blue I, II, III triptych (1961) exemplifies this late style. These large canvases feature vast fields of intense blue, punctuated by minimal yet potent black lines and red dots. They possess a meditative, almost spiritual quality, reducing his visual language to its bare essentials while maximizing its expressive impact. The simplification points towards influences from East Asian calligraphy as well as a continued distillation of his own symbolic system.

Public commissions became increasingly important. Working again with Josep Llorens Artigas, he created stunning ceramic murals, including the Wall of the Sun and Wall of the Moon for the UNESCO building in Paris (1958). He designed a vast ceramic mural for the Barcelona Airport (1970) and the beloved monumental sculpture Dona i Ocell (Woman and Bird, 1982), covered in vibrant mosaic tiles, which stands in a park in Barcelona.

A particularly unique, though less widely known, project was the large glass mosaic mural, Personnage Oiseaux (Bird Characters), created for the Edwin A. Ulrich Museum of Art at Wichita State University in Kansas (completed 1978). This complex work, reportedly involving over a million pieces of Venetian glass and marble, demonstrates his continued experimentation with materials even late in life. He also created a tapestry for the World Trade Center in New York, tragically destroyed in the September 11, 2001 attacks. These large-scale works cemented Miró's status as a major public artist, bringing his unique vision into the daily lives of people around the world.

The Miró Alphabet: Symbols and Motifs

Central to the enduring appeal and distinctiveness of Joan Miró's art is his development of a highly personal yet universally resonant symbolic language. Throughout his career, certain motifs and forms recur, evolving in meaning and appearance but always remaining recognizable elements of his unique visual alphabet. These symbols are not rigidly defined allegories but rather poetic signs, open to interpretation and evoking a range of associations related to nature, the cosmos, humanity, and the subconscious.

Common elements include stars, moons, and suns, often depicted with childlike simplicity, connecting his work to the celestial and the cosmic. Birds are frequent inhabitants of his compositions, symbolizing freedom, poetic flight, or messengers between earth and sky. The figure of the woman appears repeatedly, often abstracted into potent biomorphic shapes, representing fertility, the earth, or primal life forces. Eyes are ubiquitous, suggesting watchfulness, inner vision, or a connection to the soul.

Ladders often feature, symbolizing escape, aspiration, or a link between the terrestrial and the celestial realms. Amoebic, biomorphic forms abound, suggesting microscopic life, primal organisms, or the fluid nature of the subconscious. Simple geometric shapes – circles, squares, triangles – interact with these organic forms, creating dynamic visual tensions. Lines are rarely just outlines; they are energetic, calligraphic gestures that define form, suggest movement, or map connections across the canvas.

Miró drew inspiration for this symbolic vocabulary from diverse sources: the prehistoric cave paintings of Altamira, Catalan Romanesque frescoes, children's drawings, folk art, and the natural forms observed at Mont-roig. His symbols tap into archetypal imagery, giving his work a timeless quality. Like the Swiss artist Paul Klee, Miró created a deeply personal iconography that nonetheless speaks to universal human experiences – dreams, desires, fears, and our place in the cosmos. This rich symbolic language is key to the poetic power of his art.

Artistic Philosophy: The "Assassination of Painting" and Poetic Reality

Joan Miró famously declared his desire to "assassinate painting." This provocative statement, made in the late 1920s, should not be taken as a literal rejection of the medium he practiced throughout his life. Rather, it expressed his profound dissatisfaction with the conventions and limitations of traditional easel painting, particularly its association with bourgeois taste and commercialism. He sought to challenge established notions of what painting could be, pushing its boundaries and exploring unconventional materials and techniques.

His "assassination" was aimed at illusionistic representation, academic formulas, and the idea of painting as merely a decorative object. He wanted to move beyond surface appearances to capture a deeper, more essential reality – a poetic reality rooted in the subconscious, instinct, and the primal forces of nature. This aligns with the anti-art gestures of Dadaism, exemplified by artists like Marcel Duchamp, who questioned the very definition and status of art objects. Miró, however, channeled this rebellious spirit into creating a new kind of painting, sculpture, and graphic work, rather than abandoning these forms altogether.

He embraced techniques like automatism, collage, and working with found objects partly as a way to bypass conscious control and traditional aesthetics. He experimented with unusual supports, such as Masonite and sandpaper, and incorporated materials like tar, sand, and string into his works. This constant experimentation was part of his effort to revitalize artistic practice and discover new expressive possibilities.

Ultimately, Miró's goal was not destruction but transformation. He sought to create art that was direct, potent, and connected to the fundamental rhythms of life and the cosmos. His work aimed for a universal language that could communicate on an intuitive, emotional level, bypassing rational analysis. The "assassination" was a necessary step in clearing the ground for the creation of this profoundly original and poetic vision.

Network of Influence: Miró and His Contemporaries

Joan Miró's long career unfolded amidst a constellation of influential artists, writers, and movements, and his relationships with his contemporaries were complex, involving friendship, collaboration, influence, and sometimes, artistic divergence. His interactions within the avant-garde circles of Barcelona and Paris were crucial to his development.

His relationship with Pablo Picasso was significant. As fellow Catalans in Paris, Picasso initially acted as a mentor figure, offering support. While their artistic paths diverged – Picasso primarily exploring Cubism and its aftermath, Miró forging his unique Surrealist-inflected abstraction – they maintained a lifelong respect, representing two pillars of 20th-century Spanish art. Miró also absorbed early lessons from the structural innovations of Cubism developed by Picasso and Georges Braque.

His connection to the Surrealist movement, led by André Breton, was pivotal. Although he kept his independence, the movement's ideas about the subconscious and automatism deeply influenced him. He exhibited alongside key Surrealists like Max Ernst, Yves Tanguy, and René Magritte, and shared techniques like automatic drawing with André Masson. However, his emphasis on painterly values and poetic abstraction set him apart from the illusionistic dreamscapes of Salvador Dalí, another major Spanish Surrealist with whom he had a more distant relationship.

Miró acknowledged the influence of earlier masters like Vincent van Gogh for his expressive intensity and Paul Cézanne for his structural understanding. The bold colors of Fauvism, particularly the work of Henri Matisse, left an early mark. His symbolic language and flat, graphic style also show affinities with the work of Paul Klee. Collaborations were important, most notably his long partnership with ceramicist Josep Llorens Artigas. His friendship with sculptor Alexander Calder reflected shared sensibilities in creating playful, dynamic forms. He was also connected to the Dada movement through figures like Tristan Tzara and absorbed its spirit of revolt, akin to the anti-art stance of Marcel Duchamp. Abstract pioneers like Wassily Kandinsky also form part of the broader context for Miró's move towards non-representational art.

A Lasting Imprint on Art History

Joan Miró's impact on the course of 20th-century art is immense and multifaceted. His unique synthesis of Surrealist automatism, abstract forms, and a deeply personal symbolic language created a body of work that continues to inspire and resonate with audiences and artists worldwide. He successfully bridged the gap between European Surrealism and the burgeoning Abstract Expressionist movement in the United States.

Artists of the New York School, particularly Arshile Gorky and potentially Jackson Pollock, were drawn to Miró's exploration of automatism and his biomorphic abstractions in the 1940s. His ability to convey profound emotion and psychological depth through abstract means provided a crucial precedent for their own explorations. His emphasis on the process of creation and the expressive potential of gesture also resonated with Action Painting.

Beyond Abstract Expressionism, Miró's influence can be seen in various later art movements, including Color Field painting (in his use of large, vibrant color areas) and subsequent generations of artists exploring poetic abstraction and symbolic imagery. His playful spirit and use of bright, primary colors have also made his work widely accessible and popular, appealing even to those unfamiliar with the complexities of modern art history.

His legacy is preserved not only in the countless museums and collections that hold his work but also through dedicated institutions. The Fundació Joan Miró in Barcelona, established by the artist himself in 1975, houses a vast collection of his works and serves as a major center for the study of his art and contemporary art in general. Another foundation exists in Palma de Mallorca, preserving his later studio. Miró's relentless experimentation across media – painting, sculpture, ceramics, printmaking, tapestry, mosaic – serves as an enduring model of artistic curiosity and versatility.

The Universe of Miró

Joan Miró stands as a true giant of modern art, an artist who crafted a unique and instantly recognizable visual universe. Emerging from the rich cultural landscape of Catalonia and forged in the crucible of Parisian avant-gardism, he navigated the major art movements of his time while always maintaining his singular vision. His art is a delicate balance of seeming contradictions: childlike innocence and sophisticated composition, playful humor and profound depth, meticulous craft and spontaneous gesture.

He successfully translated the Surrealist exploration of the subconscious into a vibrant language of abstract forms and poetic symbols. His "assassination of painting" was not an act of nihilism but a radical reimagining of art's possibilities, liberating color and line to express fundamental human experiences and a deep connection to the natural and cosmic worlds. His prolific output across diverse media demonstrates an inexhaustible creativity and a lifelong commitment to experimentation.

From the detailed magic realism of The Farm to the dreamlike explosion of Harlequin's Carnival, from the wartime intensity of the "Savage Paintings" and the cosmic intimacy of the Constellations to the monumental serenity of his late abstractions and public works, Miró's journey was one of constant evolution and self-discovery. He created an art that speaks across cultures and generations, inviting viewers into a world where stars dance, birds sing in vibrant colors, and the ordinary is transformed into the extraordinary. The universe of Joan Miró remains a source of endless wonder and artistic inspiration.