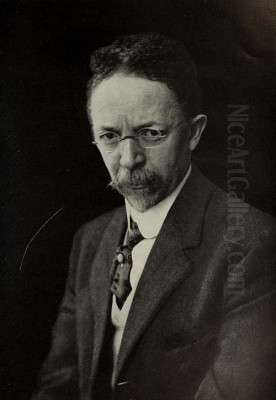

Henry Ossawa Tanner stands as a monumental figure in the annals of art history, celebrated not only for his profound artistic skill but also as the first African American painter to achieve international acclaim. His life and work offer a compelling narrative of talent, perseverance, and the transcendence of racial barriers in an era fraught with prejudice. Tanner’s canvases, often imbued with a spiritual luminosity and deep human empathy, explored both sacred religious themes and intimate scenes of African American life, leaving an indelible mark on American and global art.

Early Life and Formative Influences

Born on June 21, 1859, in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, Henry Ossawa Tanner's upbringing was steeped in intellectual and religious fervor. His father, Benjamin Tucker Tanner, was a highly educated minister and later a bishop in the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church, a prominent institution within the Black community. His mother, Sarah Elizabeth Miller Tanner, had her own remarkable story of resilience, having been born into slavery and escaping to the North via the Underground Railroad. This heritage of faith, intellectual pursuit, and the struggle for freedom undoubtedly shaped young Henry's worldview.

The Tanner family moved to Philadelphia in 1868, a city that would play a crucial role in Henry's early artistic development. Despite his father's initial hope that he might follow him into the ministry, Tanner's passion for art was undeniable from a young age. Legend has it that a walk through Fairmount Park with his father, where he saw a landscape painter at work, ignited his artistic calling around the age of thirteen. He was largely self-taught in his early years, sketching and painting whenever possible, despite periods of ill health.

Academic Pursuits and Early Challenges

In 1879, at the age of twenty, Tanner enrolled in the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA) in Philadelphia, one of the premier art institutions in the United States. This was a significant step, as he was the only African American student during his tenure. At PAFA, he studied under the influential American realist painter Thomas Eakins. Eakins, known for his rigorous approach to anatomy, direct observation, and unvarnished portrayal of subjects, became a vital mentor. Eakins's progressive teaching methods and his encouragement of Tanner's talent were crucial. Tanner became one of Eakins's favored students, and their mutual respect endured; Eakins would paint a sensitive portrait of Tanner nearly two decades after he left the Academy.

Other notable artists associated with PAFA around this period, either as students or faculty, included Thomas Anshutz, who also taught there and continued Eakins's realist tradition, and Cecilia Beaux, a highly successful female portraitist. While at PAFA, Tanner also formed a friendship with Robert Henri, who would later become a leading figure in the Ashcan School of American art.

Despite the supportive environment fostered by Eakins, Tanner faced significant racial prejudice both within the Academy and in the broader Philadelphia art scene. He later recounted painful experiences of discrimination from fellow students. These challenges, coupled with the limited opportunities for African American artists in the United States at the time, made it difficult for him to establish a successful career. After leaving PAFA around 1885, he attempted to make a living through art and photography in Philadelphia and later Atlanta, Georgia, where he briefly taught drawing at Clark University. However, commercial success remained elusive.

The Transformative Journey to Paris

A pivotal moment in Tanner's life came in 1891. With the financial support of patrons, Bishop Joseph Crane Hartzell and his wife, who recognized his talent, Tanner was able to travel to Paris, France. This move proved to be transformative. Paris, the undisputed art capital of the Western world, offered a more tolerant social atmosphere and greater opportunities for artistic growth and recognition than he had found in America.

In Paris, Tanner enrolled at the Académie Julian, a progressive art school popular with foreign students, where he studied under renowned academic painters like Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant and Jean-Paul Laurens. He also attended the Académie Colarossi. The academic training he received further honed his technical skills, particularly in drawing and composition. More importantly, Paris exposed him to a vibrant international art community and a wide range of artistic styles, from the lingering influence of Academic art to the burgeoning movements of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, and the rise of Symbolism.

Artists like James McNeill Whistler and John Singer Sargent had already established successful careers as American expatriates in Europe, demonstrating that international recognition was possible. While Tanner's style differed, the Parisian environment allowed him to develop his unique artistic voice, free from the overt racial constraints he had experienced in the United States. He found a supportive community and began to exhibit his work regularly.

Artistic Evolution: Themes and Styles

Tanner's artistic output can be broadly categorized into genre scenes depicting African American life and, most notably, religious subjects. His early works in America, and some shortly after his arrival in Paris, focused on dignified portrayals of African Americans, a conscious effort to counter the prevalent racist caricatures in popular culture.

Dignified Portrayals of African American Life

Two of his most celebrated early works are The Banjo Lesson (1893) and The Thankful Poor (1894). The Banjo Lesson, now in the collection of Hampton University Museum, depicts an elderly Black man tenderly teaching a young boy to play the banjo. The painting is remarkable for its quiet intimacy, warm lighting, and the respectful portrayal of intergenerational knowledge transfer. It directly challenged the minstrel show stereotypes that often associated the banjo with demeaning caricatures of Black people. Instead, Tanner presented a scene of dignity, love, and cultural heritage. Similarly, The Thankful Poor, showing an elderly man and a young boy saying grace before a modest meal, conveys a sense of quiet piety and familial warmth, rendered with a sensitive realism. These works demonstrated his early mastery of light and his commitment to portraying his subjects with profound humanity.

The Turn to Religious Narratives

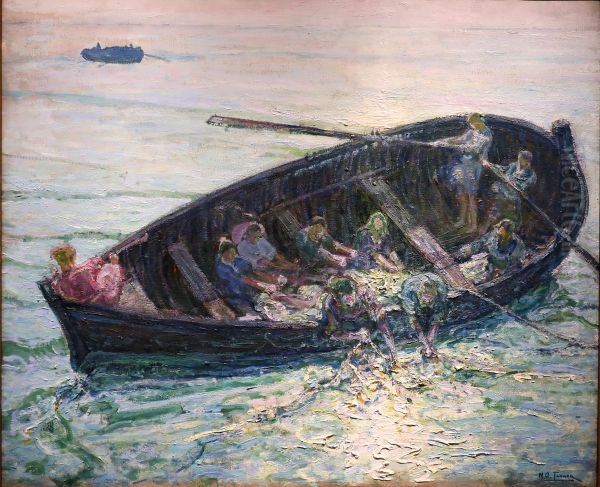

While in Paris, Tanner increasingly turned to religious themes, a subject matter that resonated deeply with his upbringing and personal faith. He believed that religious art could convey universal human emotions and spiritual truths. His travels to the Middle East, including Palestine and Egypt, beginning in 1897 (partially funded by the department store magnate Rodman Wanamaker, a significant patron of the arts), profoundly influenced his religious paintings. These journeys allowed him to experience the landscapes, light, and people of the Holy Land firsthand, lending an air of authenticity and unique atmosphere to his biblical scenes.

His religious paintings are characterized by their dramatic use of light and shadow (chiaroscuro), a rich, often jewel-toned color palette, and a deeply spiritual and emotional intensity. Works like Daniel in the Lions' Den (1895, though he painted multiple versions) garnered early acclaim. His 1896 version won an honorable mention at the Paris Salon, a prestigious annual art exhibition, marking a significant step in his international recognition.

The Resurrection of Lazarus (c. 1896) is another powerful example. Purchased by the French government for the Musée du Luxembourg, this was an extraordinary honor for an American artist, let alone an African American one. The painting captures the awe and mystery of the biblical event, with Christ depicted as a commanding yet human figure, and the onlookers reacting with a mixture of fear and wonder. The interplay of light, particularly the ethereal glow emanating from Lazarus, is masterfully handled.

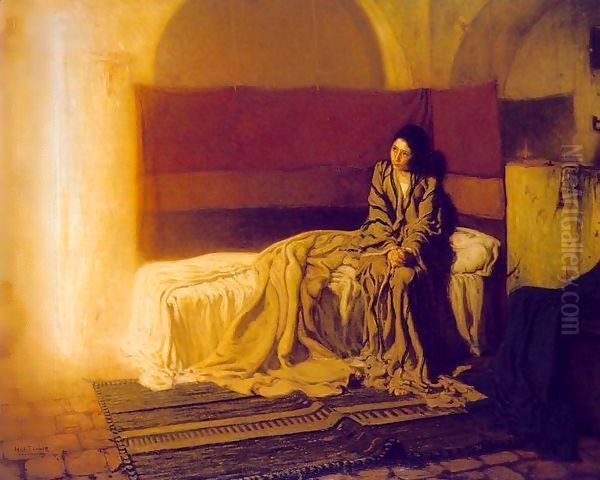

The Annunciation (1898), now in the Philadelphia Museum of Art, is one of his most iconic religious works. Tanner departed from traditional iconography, portraying Mary not as a serene, idealized European figure, but as a young, contemplative Middle Eastern peasant girl, startled and humbled by a shaft of divine light that represents the angel Gabriel. This innovative and humanizing approach was characteristic of his religious art. He sought to make these ancient stories relatable and emotionally resonant.

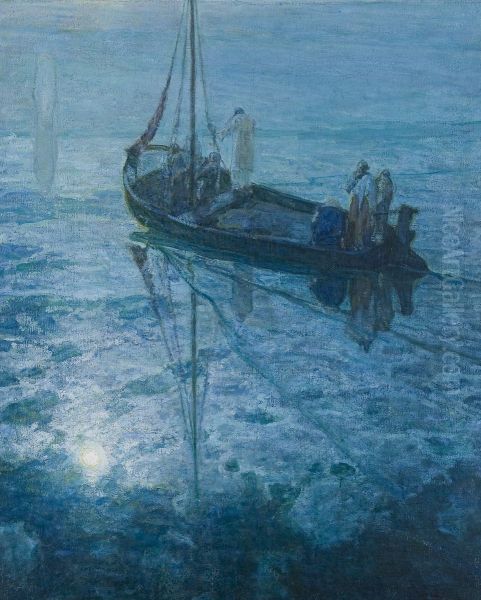

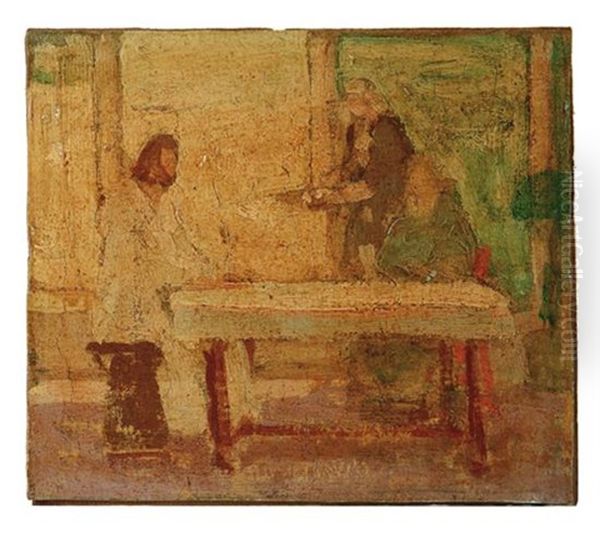

Other notable religious works include The Good Shepherd (1903), Christ and His Disciples on the Road to Bethany (c. 1905), and numerous depictions of Christ's life and teachings. His religious paintings often feature a distinctive, luminous blue, sometimes referred to as "Tanner blue," which contributes to their mystical and spiritual atmosphere.

Artistic Style: A Synthesis of Influences

Tanner's style evolved throughout his career, but it consistently demonstrated a blend of academic realism, an expressive use of color and light influenced by Impressionism and Symbolism, and a deep psychological insight. He was not strictly an adherent to any single school but rather synthesized various influences into a unique personal vision.

His training under Eakins instilled a strong foundation in realist depiction and anatomical accuracy. In Paris, he absorbed the lessons of French academic painting regarding composition and finish. However, he moved beyond strict academicism. His handling of light became a hallmark of his work – not just the bright, broken color of the Impressionists like Claude Monet or Edgar Degas, but a more focused, often spiritual or mysterious illumination that could highlight the emotional core of a scene. This aligns him with aspects of Symbolism, a movement that emphasized suggestion, mood, and inner meaning, as seen in the works of artists like Puvis de Chavannes or Odilon Redon. His travels in North Africa and the Middle East also introduced elements of Orientalism into his work, though his approach was more focused on authentic atmosphere and spiritual resonance than the often exoticized or romanticized visions of some European Orientalist painters like Jean-Léon Gérôme.

His brushwork could vary from tightly rendered passages to more painterly and expressive areas. He masterfully used color to evoke mood and atmosphere, often employing a limited palette to achieve harmonious and emotionally charged effects. The overall impression of his mature work is one of quiet contemplation, spiritual depth, and profound human empathy.

International Recognition and Continued Career

Tanner's success at the Paris Salon was a turning point. The purchase of The Resurrection of Lazarus by the French state in 1897 was a major triumph. He continued to exhibit regularly at the Salon and other prestigious venues in Europe and the United States, gaining numerous awards and accolades. In 1923, he was made a Chevalier of the Legion of Honour by the French government, one of France's highest civilian awards, a rare distinction for an American artist. His works were acquired by major American museums, including the Art Institute of Chicago and the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts.

Despite his international fame, Tanner chose to live most of his adult life in France, returning to the United States only for visits and exhibitions. He found the racial climate in France more conducive to his life and work. He married a white American opera singer, Jessie Olsson, in 1899, a union that would have faced even greater societal condemnation in the U.S. at the time. They had one son, Jesse Ossawa Tanner.

During World War I, Tanner worked for the American Red Cross in France, sketching and painting scenes from the front lines, often focusing on the contributions of African American soldiers.

Mentorship and Influence on Future Generations

Tanner became an inspirational figure and a mentor to younger African American artists who traveled to Paris to study and escape the racial discrimination in America. He offered guidance and support to artists such as William Edouard Scott, Palmer Hayden, Hale Woodruff, and Aaron Douglas, a key figure in the Harlem Renaissance. He shared his knowledge of the Parisian art scene and encouraged them in their artistic pursuits. His success demonstrated that it was possible for an African American artist to achieve international recognition, paving the way for future generations. While he was not directly involved in the Harlem Renaissance movement due to his expatriate status, his achievements served as a powerful example and source of pride.

Later Years and Enduring Legacy

Henry Ossawa Tanner continued to paint and exhibit into his later years, primarily focusing on religious themes. He passed away in Paris on May 25, 1937, at the age of 77.

His legacy is multifaceted. Artistically, he was a master of light, color, and emotional expression, creating works of enduring beauty and spiritual depth. Historically, he broke significant racial barriers, becoming a pioneering figure in American art. His dignified portrayals of African American life offered a crucial counter-narrative to racist stereotypes, and his religious paintings achieved universal appeal.

Tanner's work demonstrated that art could transcend racial and national boundaries. He proved that an African American artist could compete and succeed on the international stage based on talent and artistic merit. His paintings continue to be celebrated in museums and collections worldwide, and his life story remains an inspiration. He is recognized not just as a great African American artist, or a great American artist, but simply as a great artist whose contributions have enriched the broader tapestry of world art. His journey from Pittsburgh to international acclaim is a testament to his extraordinary talent and unwavering dedication to his craft in the face of adversity. His light, both in his canvases and in his historical impact, continues to shine brightly.