Sir John Everett Millais stands as one of the towering figures of nineteenth-century British art. A painter and illustrator of prodigious talent and immense popularity, his career traced a remarkable arc from youthful rebellion as a founder of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood to becoming a pillar of the Victorian art establishment, culminating in the presidency of the Royal Academy. His life and work encompass technical brilliance, controversial subject matter, complex personal relationships, and a fascinating negotiation between artistic ideals and commercial success. Millais's art, particularly iconic works like Ophelia, remains deeply embedded in the cultural consciousness, embodying both the intricate detail of Pre-Raphaelitism and the broader sentiments of the Victorian era.

The Emergence of a Prodigy

John Everett Millais was born in Southampton on June 8, 1829, to a prominent Jersey family. His artistic gifts were apparent from an exceptionally early age. Recognizing his extraordinary talent, his mother, a woman with a strong interest in art and culture, was instrumental in persuading the family to move to London to provide him with the best possible artistic education. Her belief in his potential was well-founded; Millais's precocity was astonishing.

In 1840, at the unprecedented age of eleven, he was admitted to the Royal Academy Schools, becoming its youngest ever student. This feat immediately marked him as a figure of exceptional promise within the London art world. During his time at the Academy, he proved a brilliant student, winning numerous prizes and mastering the technical skills expected of an aspiring painter within the academic tradition, a tradition largely shaped by the legacy of figures like Sir Joshua Reynolds. However, Millais and a circle of like-minded young artists were growing dissatisfied with the prevailing artistic conventions.

Founding the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood

By the late 1840s, the Royal Academy's teachings, emphasizing idealized forms and compositional structures derived from High Renaissance masters like Raphael, felt stale and artificial to Millais and his friends. In 1848, alongside fellow disillusioned students William Holman Hunt and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Millais co-founded the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (PRB). This secret society, later expanded to include James Collinson, Frederic George Stephens, Thomas Woolner, and William Michael Rossetti (Dante Gabriel's brother), aimed to revolutionize British art.

The Pre-Raphaelites rejected the perceived academic dogma and Mannerist distortions that followed Raphael. Instead, they advocated a return to the artistic principles they believed characterized Italian art before Raphael – namely, intense colour, abundant detail, complex compositions, and, crucially, truth to nature. They sought to imbue their art with a new level of realism, sincerity, and moral seriousness, often drawing inspiration from literature, religion, and medieval subjects, rendered with meticulous attention to observed detail.

Early Masterpieces and Critical Storms

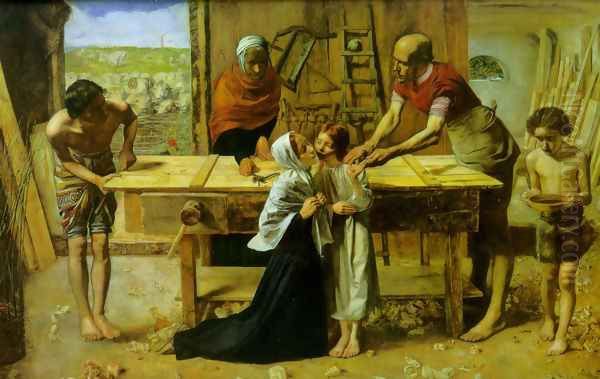

Millais quickly became the technical standard-bearer for the PRB, producing works of astonishing detail and vibrant colour. His early paintings exemplified the Brotherhood's core tenets. Isabella (1849), based on a poem by Keats, showcased the group's interest in literary themes and detailed, symbolic interiors. However, it was Christ in the House of His Parents (also known as The Carpenter's Shop), exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1850, that ignited a firestorm of controversy.

The painting depicted the Holy Family in a realistic, working-class carpenter's workshop, complete with wood shavings and everyday tools. This unflinching realism, particularly the portrayal of Joseph, Mary, and the young Jesus without traditional idealization, shocked critics and the public. The influential novelist Charles Dickens famously savaged the work in his periodical Household Words, describing the figure of Mary as hideous and the scene as degrading. The criticism was fierce, accusing Millais and the PRB of blasphemy and ugliness.

Despite the hostility, Millais persisted, supported initially by the influential critic John Ruskin, who saw merit in the PRB's commitment to detailed observation. Millais produced a series of masterpieces in the early 1850s that cemented his reputation, including Mariana (1851), The Huguenot (1852), and arguably his most famous work, Ophelia (1851-52). Ophelia, depicting the tragic drowning scene from Shakespeare's Hamlet, is renowned for its breathtakingly detailed rendering of the natural world, painted painstakingly outdoors on the Hogsmill River in Surrey, and the poignant portrayal of the doomed heroine, modelled by Elizabeth Siddal (who would later marry Rossetti).

The Ruskin Connection and Personal Upheaval

The relationship with John Ruskin proved pivotal in Millais's life, both professionally and personally. Ruskin became a champion of the Pre-Raphaelites, defending their work against critical attacks and praising their truth to nature. In the summer of 1853, Ruskin invited Millais to join him and his wife, Euphemia 'Effie' Gray Ruskin, on a trip to Glenfinlas in Scotland. During this trip, Millais began his famous portrait of Ruskin standing by a rocky waterfall, a work that exemplifies the PRB's detailed geological and botanical accuracy.

However, the trip also precipitated a personal crisis. Millais and Effie Ruskin grew close, while the marriage between Effie and Ruskin remained unconsummated and deeply unhappy. Effie subsequently left Ruskin, and their marriage was annulled in 1854 on grounds of non-consummation, a significant public scandal at the time. In 1855, Millais married Effie. This event caused a permanent rupture with Ruskin, who felt betrayed, and created social difficulties for the couple, particularly for Effie, who was ostracized by some segments of society, including Queen Victoria initially. The marriage, however, was a happy one, producing eight children, and marked a turning point in Millais's life and, arguably, his art.

A Shift in Style: Evolution and Criticism

Following his marriage and the dissolution of the original PRB circle (though its influence persisted), Millais's artistic style began to evolve. While still grounded in keen observation, his brushwork gradually became broader and freer, his compositions less densely packed with symbolic detail, and his subject matter often shifted towards themes with wider popular appeal. Works like The Blind Girl (1856), with its poignant social commentary and detailed landscape, and Autumn Leaves (1856), evoking mood and transience, still showed Pre-Raphaelite intensity but hinted at a developing interest in atmosphere and sentiment.

This stylistic shift accelerated through the late 1850s and 1860s. Some critics, including former allies like Dante Gabriel Rossetti and later William Morris, viewed this change negatively, suggesting Millais was abandoning the radical principles of the PRB in favour of commercial success and popular acclaim. They felt his work was losing its intensity and intellectual rigour. However, others interpreted this evolution as a sign of growing artistic confidence and maturity, a move away from the painstaking, almost obsessive detail of his youth towards a more fluid and expressive handling of paint, perhaps influenced by masters like Velázquez, whom Millais greatly admired. The demands of supporting a large family undoubtedly also played a role in his choice of more marketable subjects.

Master of Landscape and Nature

Throughout his career, Millais retained a deep love for the natural world, particularly the landscapes of Scotland, where he frequently spent summers painting outdoors. His landscape paintings became an important part of his later output, showcasing his evolving style. While the intense, almost microscopic detail of early PRB backgrounds lessened, his ability to capture the specific mood and atmosphere of a place remained powerful.

Chill October (1870), painted near the River Tay in Perthshire, is a prime example of his mature landscape style. It conveys a sense of autumnal melancholy and the raw beauty of the Scottish scenery with broader brushstrokes and a focus on light and atmosphere, yet still grounded in careful observation. Unlike the dramatic sublimity sought by J.M.W. Turner or the pastoral idylls of John Constable, Millais's landscapes often focused on specific, sometimes melancholic, moments in nature, rendered with a powerful sense of realism and place. These works were highly popular and further cemented his reputation.

Portraiture: Capturing the Victorian Age

Millais became one of the most sought-after portrait painters of the Victorian era. His success in this genre contributed significantly to his fame and fortune. He possessed a remarkable ability to capture not only a sitter's likeness but also their character and social standing. His portraits often employed the broader brushwork characteristic of his later style, yet they retained a strong sense of presence and psychological insight.

He painted many of the most prominent figures of the age, creating definitive images of statesmen like William Gladstone and Benjamin Disraeli, literary giants such as Alfred, Lord Tennyson and Anthony Trollope, fellow artists like Frederic Leighton, society beauties like Lillie Langtry, and church leaders like Cardinal Newman. These portraits serve as a veritable gallery of the Victorian establishment, rendered with technical assurance and an understanding of the sitter's public persona. While less radical than his early work, his portraiture was highly accomplished and commercially successful.

Illustration, Popularity, and the 'Bubbles' Controversy

Beyond easel painting, Millais was a highly successful and influential illustrator. During the 1850s and 1860s, often considered a golden age of British illustration, he contributed numerous designs for books and periodicals, including Moxon's illustrated edition of Tennyson's poems (alongside Rossetti and Hunt) and novels by Anthony Trollope for the Cornhill Magazine. His illustrations, often characterized by strong compositions and emotional clarity, reached a wide audience and significantly enhanced his public profile. Contemporaries like Arthur Hughes and Frederick Sandys were also part of this illustration boom.

Millais's immense popularity sometimes led to controversy regarding the relationship between art and commerce. The most famous instance involved his painting A Child's World (1886), depicting his grandson Willie James blowing bubbles. The painting was acquired by Sir William Ingram of the Illustrated London News, who subsequently sold the copyright to A & F Pears, manufacturers of Pears Soap. Pears added a bar of their soap into the image and used it extensively as an advertisement under the title Bubbles. While Millais protested the addition, he had sold the copyright. The incident sparked widespread debate about artistic integrity and the commercial appropriation of fine art, with critics like Marie Corelli lambasting Millais for allowing his art to be used for advertising, seeing it as the ultimate "selling out."

Later Works and Aesthetic Connections

In his later subject pictures, Millais often turned to historical themes, childhood, and narratives emphasizing bravery, pathos, or imperial sentiment. Works like The Boyhood of Raleigh (1870) and The North-West Passage (1874) captured the Victorian imagination with their blend of historical narrative and emotional appeal. While the intense detail of his youth was gone, these paintings showcased his mastery of composition, colour, and storytelling, albeit in a more conventional vein.

His later style, with its looser brushwork, emphasis on mood, and often beautiful subjects, can be seen in dialogue with the burgeoning Aesthetic Movement. Although not an Aesthete in the manner of James McNeill Whistler or Albert Moore, Millais's later focus on painterly qualities and evocative sentiment resonated with some aspects of the "art for art's sake" philosophy. His technical facility and exploration of different painterly effects certainly influenced younger artists, including the Anglo-American portraitist John Singer Sargent, whose bravura brushwork owes a debt to painters like Millais and Velázquez.

Honours, Final Years, and Legacy

The latter part of Millais's career was marked by immense public and official recognition. He had been elected an Associate of the Royal Academy (ARA) in 1853 and a full Royal Academician (RA) in 1863. In 1885, he was created a Baronet, one of the first artists to receive such a hereditary honour. His status as the nation's preeminent painter seemed secure. The culmination of his career came in February 1896 when, following the death of Lord Leighton, Millais was overwhelmingly elected President of the Royal Academy (PRA).

Tragically, his tenure was cut short. He was already suffering from throat cancer, which rapidly worsened. Despite his illness, he endeavoured to fulfil his duties and continued to work when possible. Sir John Everett Millais died on August 13, 1896, just months after assuming the presidency. In recognition of his immense contribution to British art, he was buried in St. Paul's Cathedral, alongside other artistic giants like Sir Christopher Wren, Sir Joshua Reynolds, J.M.W. Turner, and his immediate predecessor, Lord Leighton.

Re-evaluating a Victorian Titan

The academic and critical assessment of Sir John Everett Millais has mirrored the trajectory of his career – immense admiration for his early, revolutionary work, followed by a period where his later, more popular style was often dismissed as a decline or a compromise. For much of the 20th century, modernist critics tended to favour the radicalism of the early PRB phase over the perceived sentimentality and commercialism of his later output. Figures like William Morris's critique of Millais "selling out" echoed through subsequent evaluations.

However, more recent scholarship has offered a more nuanced perspective. Millais's entire oeuvre is increasingly viewed as a complex response to the changing artistic, social, and commercial landscape of the 19th century. His technical brilliance is undeniable throughout his career. His early work remains celebrated for its revolutionary impact and visual intensity. His later work, including the portraits, landscapes, and subject pictures, is now often appreciated for its technical mastery, its reflection of Victorian culture, and its influence on subsequent artists, including members of the Aesthetic Movement and painters like Sargent. His illustrations are recognized for their significant contribution to Victorian visual culture. Even the Bubbles incident is seen as a key moment in the history of art and advertising. Millais's journey from avant-garde rebel, alongside Hunt, Rossetti, and briefly associating with figures like Ford Madox Brown and Edward Burne-Jones (who represented a later phase of Pre-Raphaelitism), to establishment figurehead, rivalled in public esteem only perhaps by G.F. Watts or Lord Leighton, makes him a uniquely fascinating figure.

Conclusion

Sir John Everett Millais remains a central and compelling figure in the history of British art. From his beginnings as a child prodigy and a founding member of the radical Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, challenging the artistic norms of his day with works of startling realism and detail, he evolved into the most popular and successful painter of the high Victorian era. While his stylistic changes drew criticism, his technical skill, narrative power, and ability to capture the spirit of his age were consistent throughout his prolific career. His life encompassed artistic revolution, public controversy, personal drama, and immense worldly success, leaving behind a legacy of iconic images that continue to resonate and define our understanding of Victorian art and culture.