Hermann Hendrich (1854-1931) stands as a fascinating, if somewhat overlooked, figure in the landscape of German art at the turn of the 20th century. A painter, illustrator, and even an architectural visionary, Hendrich dedicated his artistic endeavors to the potent themes of Germanic mythology, Wagnerian opera, and a romanticized vision of Germany's ancient past. His work is deeply entwined with the cultural currents of his time, particularly the burgeoning Jugendstil (Art Nouveau) movement, the enduring legacy of Romanticism, and the often problematic Völkisch ideology that sought to define a unique German cultural identity. Through his evocative paintings and ambitious architectural-artistic projects, Hendrich aimed to create immersive experiences, or Gesamtkunstwerke (total works of art), that would transport viewers into a world of legend and national pride.

Early Life and Formative Influences

Born on October 31, 1854, in Heringen an der Werra, in the German state of Hesse, Hermann Hendrich's early life set him on a path somewhat removed from traditional academic art training. He initially undertook an apprenticeship as a lithographer, a skill that would later inform his illustrative work. His early career saw him working in various cities, including Nordhausen. However, a pivotal moment in his artistic awakening was his encounter with the music dramas of Richard Wagner.

Wagner's powerful reinterpretations of Norse and Germanic myths, particularly Der Ring des Nibelungen and Parsifal, resonated deeply with Hendrich. The composer's ambition to create a Gesamtkunstwerk, where music, drama, poetry, and stagecraft coalesced into a unified artistic experience, profoundly influenced Hendrich's own aspirations. He saw in Wagner's work a model for how art could tap into the deepest wellsprings of national consciousness and spiritual yearning. This Wagnerian influence would become a recurring motif throughout his career, inspiring numerous paintings and shaping the conceptual framework for his larger projects.

Further artistic development occurred during his travels. Stays in Berlin, Munich, and even a period in Norway, where he was exposed to traditional Nordic wooden architecture (Stave churches, for example), broadened his visual vocabulary. The rugged landscapes and mythic atmosphere of Scandinavia likely reinforced his predilection for themes of nature, ancient sagas, and the mystical. He also spent time in the United States, though this period seems less directly impactful on his core thematic concerns than his European experiences.

Artistic Style: A Confluence of Romanticism, Symbolism, and Jugendstil

Hermann Hendrich's artistic style is a complex tapestry woven from several distinct yet interrelated threads. At its heart lies a deep-seated Romanticism, inherited from 19th-century masters like Caspar David Friedrich and Arnold Böcklin. This is evident in his dramatic landscapes, often imbued with a sense of awe, mystery, and the sublime power of nature. Mountains, forests, and atmospheric light effects are common, serving as backdrops for mythological or legendary scenes.

Symbolism also plays a crucial role in Hendrich's oeuvre. Like contemporaries such as Max Klinger or Franz von Stuck, Hendrich sought to convey deeper meanings and spiritual truths through his imagery. His figures are often archetypal, representing forces of nature, mythological beings, or abstract concepts. The narratives he depicted were less about literal representation and more about evoking moods, emotions, and a sense of the numinous.

The influence of Jugendstil, the German variant of Art Nouveau, is apparent in the decorative qualities of his work, the flowing lines, and the attempt to integrate art into everyday life and architecture. While perhaps not as overtly stylized as some Jugendstil practitioners like Gustav Klimt in Vienna or Otto Eckmann in Germany, Hendrich embraced the movement's emphasis on craftsmanship and the creation of harmonious artistic environments. His architectural projects, in particular, embody the Jugendstil ideal of the Gesamtkunstwerk.

The Walpurgishalle: A Temple to Goethe and Germanic Myth

One of Hendrich's most significant and enduring achievements is the Walpurgishalle (Walpurgis Hall), located on the Hexentanzplatz (Witches' Dance Floor) near Thale in the Harz Mountains. Conceived and designed by Hendrich, and built between 1900 and 1901, this unique structure is a testament to his artistic vision and his immersion in German literary and folkloric traditions. The Hexentanzplatz itself is a site steeped in legend, traditionally believed to be a gathering place for witches on Walpurgis Night (the eve of May Day).

The architectural design of the Walpurgishalle, executed by architect Bernhard Sehring, draws inspiration from traditional Nordic wooden structures, reflecting Hendrich's appreciation for ancient Germanic building forms. It was intended as a "temple" dedicated to Goethe's Faust, specifically the famous Walpurgis Night scenes from the play. Hendrich himself adorned the interior with a cycle of five large-scale paintings depicting key moments from this literary masterpiece.

These murals include:

Mephistopheles beschwört die Irrlichter (Mephistopheles Summons the Will-o'-the-Wisps)

Mammonshöhle (Mammon's Cave), depicting the god of wealth in a fiery grotto.

Hexenringelreihen am Blocksberg (Witches' Dance on the Blocksberg)

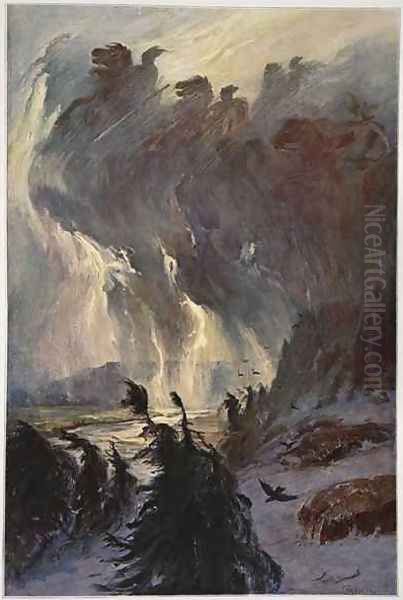

Windsbraut (The Wind Bride or Storm Spirit)

Gretchens Erscheinung (Gretchen's Apparition)

Two additional lunette paintings further enhance the thematic program. Hendrich's paintings in the Walpurgishalle are characterized by their dramatic lighting, swirling compositions, and a palpable sense of the supernatural. They effectively translate the demonic revelry and mystical atmosphere of Goethe's text into visual form. The hall itself, with its rustic wooden construction and Hendrich's evocative art, creates an immersive environment that seeks to draw the visitor into the world of myth and legend. The project was controversial, with some critics viewing its overt pagan and mystical themes with suspicion, but it undeniably became a significant cultural landmark.

The Sagenhalle: Celebrating the Legends of Rübezahl

Following the success and notoriety of the Walpurgishalle, Hendrich embarked on another ambitious project: the Sagenhalle (Hall of Legends). This was constructed in Schreiberhau (now Szklarska Poręba, Poland) in the Riesengebirge (Giant Mountains), a region rich in its own folklore. The Sagenhalle, completed in 1903, was dedicated to the legends of Rübezahl, the powerful and often capricious mountain spirit said to inhabit these peaks.

Similar to the Walpurgishalle, the Sagenhalle was conceived as a Gesamtkunstwerk, where architecture and painting would unite to tell a story. Hendrich created a cycle of eight large paintings for the hall, each illustrating an episode from the Rübezahl legends. These works showcased his ability to depict the wild, untamed nature of the mountains and the enigmatic character of the spirit himself. The themes explored included Rübezahl's interactions with humans, his control over the weather, and his role as a guardian of the mountains.

The Sagenhalle, like its Harz counterpart, aimed to connect visitors with a romanticized Germanic past and local folklore. It served as a cultural focal point, celebrating regional identity through the lens of myth. Unfortunately, the Sagenhalle in Schreiberhau did not survive in its original form, a fate shared by other structures associated with the Völkisch movement after World War II due to shifting political and cultural landscapes.

Other Notable Works and Thematic Preoccupations

Beyond these major architectural-artistic endeavors, Hermann Hendrich was a prolific painter and illustrator. His easel paintings often revisited themes from Wagnerian opera. Works like Szene Aus Wagners Ring (Scene from Wagner's Ring, 1913) demonstrate his continued fascination with the composer's epic cycle. These paintings are typically characterized by their dramatic compositions, rich, often dark, color palettes, and a focus on moments of high emotional intensity or mystical significance from the operas. He produced numerous illustrations for editions of Wagner's works, helping to visualize these complex narratives for a wider audience.

Another recurring motif in Hendrich's work is the "Irrlicht" or "Will-o'-the-wisp." His painting Will-o'-the-Wisp and the Snake (late 19th century) is a prime example. These elusive, flickering lights, often associated with bogs and marshes in European folklore, held a particular fascination for artists of a Symbolist bent. For Hendrich, they likely represented the mysterious, sometimes deceptive, forces of nature and the unseen world. His depictions often feature eerie, atmospheric landscapes where these spectral lights dance, creating a sense of unease and wonder.

His landscapes, even without explicit mythological figures, often carry a strong emotional charge. He was adept at capturing the mood of a scene, whether it be the solemnity of a moonlit forest, the grandeur of a mountain peak, or the brooding atmosphere of an approaching storm. These works connect him to the long tradition of German Romantic landscape painting, pioneered by artists like Caspar David Friedrich, though Hendrich's style is filtered through the lens of late 19th-century Symbolism and Jugendstil aesthetics.

The Völkisch Movement and Hendrich's Cultural Nationalism

It is impossible to fully understand Hermann Hendrich without considering his involvement with the Völkisch movement. This was a broad, multifaceted cultural and political phenomenon in Germany from the late 19th century through the Nazi era. It emphasized a romanticized vision of German identity rooted in ancient Germanic traditions, folklore, paganism, and a supposed racial purity. While not all adherents were proto-Nazi, the movement's ideas certainly contributed to the intellectual climate that allowed National Socialism to take root.

Hendrich was a co-founder of the Werdandi-Bund in 1903, an organization dedicated to the "renewal of German life on a Germanic-Christian basis." This group, and others like it, sought to counter what they perceived as the negative effects of modernity—industrialization, urbanization, and materialism—by promoting a return to supposedly authentic German values and traditions. Art played a crucial role in this endeavor, with artists like Hendrich, Fidus (Hugo Höppener), Franz Stassen, and Ludwig Fahrenkrog creating works that celebrated Germanic myths, heroes, and landscapes.

Hendrich's architectural projects, the Walpurgishalle and the Sagenhalle, can be seen as physical manifestations of Völkisch ideals. They were intended as sites of cultural pilgrimage, places where Germans could connect with their ancestral heritage and experience a sense of national belonging. His choice of themes—Goethe's Faust (a cornerstone of German literature), the legends of Rübezahl, and Wagnerian opera—all served to reinforce this cultural nationalist agenda.

While Hendrich's art undoubtedly resonated with many Germans seeking a sense of identity and spiritual grounding in a rapidly changing world, its association with the Völkisch movement also casts a shadow. The movement's exclusionary and often racist undertones are problematic from a contemporary perspective. It is important to analyze Hendrich's work within this complex historical context, acknowledging both its artistic merits and its entanglement with a challenging ideology.

Contemporaries and Artistic Milieu

Hermann Hendrich operated within a vibrant and diverse artistic milieu. His Romantic and Symbolist leanings placed him in dialogue with artists across Europe. In the German-speaking world, Arnold Böcklin was a towering figure whose mythological paintings, such as Isle of the Dead, had a profound impact on a generation of artists, likely including Hendrich. Max Klinger, with his intricate prints and psychologically charged sculptures and paintings, explored similar themes of myth, dream, and the subconscious. Franz von Stuck, a co-founder of the Munich Secession, also delved into mythological and allegorical subjects, often with a more sensual and overtly dramatic flair.

The Jugendstil movement provided another important context. Artists like Otto Eckmann and Peter Behrens were key figures in German Jugendstil, applying its principles to graphic design, decorative arts, and architecture. While Hendrich's style was perhaps less overtly decorative than some of his Jugendstil contemporaries, his commitment to the Gesamtkunstwerk ideal and his integration of art and architecture align him with the movement's core tenets. The influence of the Vienna Secession, led by figures like Gustav Klimt, also permeated the artistic atmosphere of Central Europe, promoting a break from academic historicism and an embrace of modern, decorative styles.

In the realm of mythological and historical illustration, Hendrich's work can be compared to that of artists like Gustav Doré, whose dramatic engravings for works like Dante's Inferno or the Bible set a high standard for narrative illustration. Édouard Riou, another prolific French illustrator, also contributed to the visual culture of the 19th century with his depictions of adventure and fantasy.

Within the more specific circle of artists associated with Wagnerian themes and Völkisch ideals, Hendrich found common cause with figures like Fidus (Hugo Höppener), whose ethereal and often esoteric imagery became iconic for the youth movement and various reform movements. Franz Stassen was another prominent illustrator of Wagnerian operas and Germanic sagas, sharing Hendrich's commitment to these national themes. Ludwig Fahrenkrog, also a painter and writer, was deeply involved in Germanic neopagan movements and created art that reflected these beliefs. Hans Thoma, though perhaps more rooted in a folk-art inspired realism, also painted scenes from Wagner and German legends, contributing to this broader cultural current.

The competitive landscape of the art world meant that Hendrich, while achieving a degree of recognition, particularly for his specialized niche, might not have attained the same level of mainstream fame as some of his contemporaries who engaged with more modernist or avant-garde trends. His focus on a specific set of national and mythological themes, while appealing to a certain segment of the populace, perhaps limited his broader international appeal compared to artists exploring more universal or formally innovative concerns.

Controversies and Reception

Hermann Hendrich's work, particularly his architectural projects and his association with the Völkisch movement, was not without controversy. The Walpurgishalle, with its explicit pagan themes and its location on the "Witches' Dance Floor," was seen by some conservative elements as promoting superstition or un-Christian ideas, despite Hendrich's own involvement in the Werdandi-Bund which sought a "Germanic-Christian" synthesis.

More broadly, the Völkisch movement itself was divisive. While it attracted many who were genuinely seeking spiritual and cultural renewal, its nationalist and often racialized undertones were criticized by liberals and internationalists. Artists like Hendrich, who dedicated their talents to promoting Völkisch ideals, were inevitably caught up in these debates. Their work could be seen as either a noble attempt to preserve and celebrate national heritage or as a form of cultural chauvinism.

The reception of his art was thus often filtered through the lens of these broader cultural and political debates. For those who shared his enthusiasm for Germanic mythology, Wagner, and a romanticized national past, Hendrich's work was inspiring and deeply meaningful. For others, it may have appeared anachronistic, overly sentimental, or ideologically suspect. His relative obscurity today, compared to some of his more modernist contemporaries, might be partly attributed to the shifting cultural tides that rendered the Völkisch movement and its artistic expressions deeply problematic after the Nazi era.

Legacy and Enduring Influence

Hermann Hendrich passed away on July 18, 1931, in Schreiberhau, the site of his Sagenhalle. His legacy is a complex one. While he may not be a household name in the annals of art history, his contributions are significant within specific contexts. The Walpurgishalle in Thale remains a popular tourist attraction and a unique example of Jugendstil architecture and thematic art. It stands as a tangible monument to his vision, allowing contemporary visitors to experience something of the Gesamtkunstwerk he intended.

His paintings and illustrations continue to be of interest to scholars of German Romanticism, Symbolism, Jugendstil, and the Völkisch movement. They provide valuable insights into the cultural preoccupations of Germany at the turn of the 20th century, a period of intense social change, national aspiration, and ideological ferment. His depictions of Wagnerian scenes remain compelling visual interpretations of the composer's music dramas.

While some of his projects, like the Sagenhalle, have been lost or altered, and the Völkisch ideology he espoused is now widely discredited, Hendrich's work serves as a reminder of the power of art to shape and reflect cultural identity. He was an artist who passionately believed in the importance of myth, legend, and a connection to the ancestral past as sources of spiritual and national strength. His attempt to create immersive artistic experiences, blending architecture, painting, and narrative, prefigures later developments in environmental art and thematic design.

Conclusion

Hermann Hendrich was an artist deeply embedded in the cultural and intellectual currents of his time. A fervent admirer of Richard Wagner, a proponent of Germanic mythology, and an active participant in the Völkisch movement, he channeled his talents into creating art that was both romantic and nationalistic. His major achievements, the Walpurgishalle and the Sagenhalle, stand as ambitious attempts to realize the ideal of the Gesamtkunstwerk, immersing viewers in worlds of legend and folklore. While his association with the Völkisch movement complicates his legacy, his artistic skill, his evocative depictions of myth and nature, and his unique architectural visions secure him a distinctive place in the history of German art. He remains a compelling figure for understanding the complex interplay of art, culture, and ideology in the years leading up to and during the German Empire and the Weimar Republic.