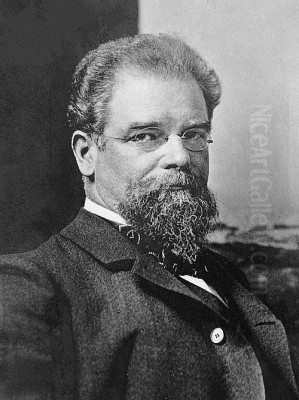

Max Klinger stands as a towering figure in German art at the turn of the 20th century. Born in Leipzig on February 18, 1857, and passing away in Großjena, near Naumburg, on July 5, 1920, Klinger navigated the complex artistic currents of his time, leaving an indelible mark as a painter, sculptor, and, most notably, a printmaker. He was a pivotal artist within the Symbolist movement and a key representative of Jugendstil, the German variant of Art Nouveau. His work, often characterized by a unique blend of meticulous realism and fantastical imagination, delved into profound themes of life, death, love, and the human psyche, influencing generations of artists who followed.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Max Klinger emerged from a prosperous background in Leipzig, which afforded him the opportunity to pursue his artistic inclinations seriously. His formal training began at the Grand Ducal Baden Art School in Karlsruhe, a respected institution where he honed his foundational skills. Seeking further development, he moved to the prestigious Royal Academy of Arts in Berlin.

During his formative years in Berlin, Klinger absorbed various influences. He studied under figures like Karl Gussow, known for his technical proficiency. Critically, he also engaged with the prevailing artistic climate, which included the powerful realism of established masters such as Adolph Menzel. While respecting realist traditions, Klinger quickly demonstrated an independent spirit, seeking avenues beyond mere mimesis. His early works already hinted at a departure from straightforward representation towards more complex, allegorical content.

His official debut came at the Berlin Academy exhibition, where his early painting, reportedly titled Eva und die Zukunft (Eve and the Future) from 1878, garnered attention. Even at this stage, his willingness to tackle ambitious themes and employ unconventional imagery set him apart from many contemporaries. This period laid the groundwork for his later explorations into the symbolic and the psychological, establishing his trajectory as an artist unafraid to confront the deeper, often darker, aspects of human existence.

The Ascendancy of the Printmaker

While Klinger achieved recognition in painting and sculpture, his most revolutionary contributions arguably lie in the realm of printmaking, particularly etching. He approached graphic arts not as a secondary pursuit or a means of reproducing paintings, but as a primary medium capable of expressing complex ideas uniquely suited to its linear and tonal possibilities. Klinger became one of the most prolific and innovative printmakers of the late 19th century.

He mastered various etching and aquatint techniques, often combining them to achieve rich textures and dramatic contrasts of light and shadow. His dedication to the medium was philosophical as well as technical; he believed that graphic art, particularly in series or cycles, could explore narrative and psychological themes with a depth and intimacy distinct from monumental painting. He articulated these ideas in his influential essay "Malerei und Zeichnung" (Painting and Drawing) in 1891, arguing for the unique expressive potential of the graphic arts.

Klinger's print cycles are central to his oeuvre. These series of interconnected images allowed him to develop complex narratives and explore multifaceted themes, often drawing on mythology, literature, music, and his own vivid imagination. They function almost like visual novels or poems, inviting viewers to contemplate the progression of images and their cumulative meaning.

Paraphrase on the Finding of a Glove: A Dreamlike Odyssey

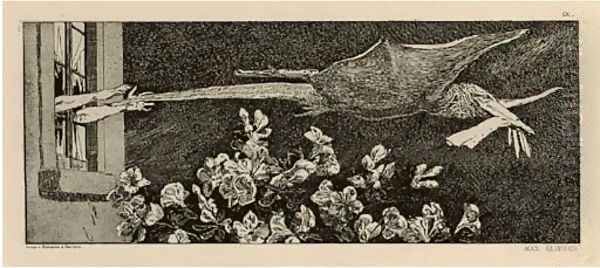

Among Klinger's most celebrated and analyzed works is the print cycle Ein Handschuh (A Glove), more fully titled Paraphrase über den Fund eines Handschuhs (Paraphrase on the Finding of a Glove), published in 1881 but conceived earlier. This series of ten etchings and aquatints is a landmark of Symbolist art and a fascinating precursor to Surrealism.

The narrative, such as it is, originates from a seemingly trivial incident: the artist finding a lady's glove at an ice-skating rink in Berlin. However, in Klinger's hands, this mundane event becomes the catalyst for a bizarre and psychologically charged dream sequence. The glove transforms into an object of intense fascination, desire, and anxiety, taking on a life of its own as it appears in increasingly strange and unsettling scenarios.

The plates depict the glove being stolen by a pterodactyl-like creature, worshipped on an altar, washed ashore by waves, and haunting the artist's dreams. The series explores themes of erotic obsession, fetishism, male anxiety, and the power of the subconscious mind. Its dreamlike logic and juxtaposition of the ordinary (the glove) with the fantastical prefigured the explorations of artists like Max Ernst and Salvador Dalí decades later. The Glove cycle cemented Klinger's reputation as an artist capable of plumbing the depths of the psyche with startling originality.

Exploring Love, Life, and Death in Print

Following the success of the Glove series, Klinger continued to produce ambitious print cycles that tackled fundamental aspects of the human condition. Eine Liebe (A Love), published in 1887, presents a narrative in ten plates detailing the course of a passionate but ultimately tragic love affair. It moves from initial attraction and intimacy through societal judgment, abandonment, and despair, possibly culminating in an abortion or the woman's demise. The series reflects a pessimistic worldview, perhaps influenced by philosophers like Arthur Schopenhauer, and offers a stark commentary on societal constraints and the vulnerability of women.

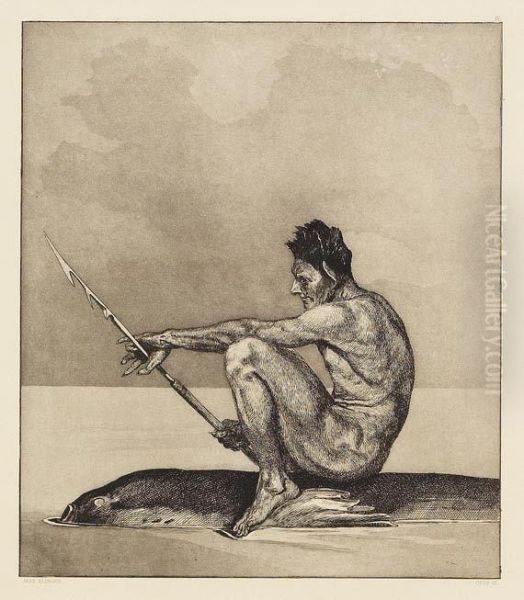

Another significant cycle is Vom Tode, Zweiter Teil (On Death, Part II), created between 1898 and 1909 (following an earlier On Death, Part I). This series confronts mortality directly, depicting death not as a single event but as an omnipresent force intertwining with life. Images range from the allegorical (Death as a reaper, a seducer) to the starkly realistic (peasants succumbing to hardship). The cycle showcases Klinger's technical mastery and his ability to evoke powerful emotions, from terror and grief to a sense of inevitable fate.

Works like Into the Gutters, an etching depicting grotesque figures pushing a young woman into a sewer, further highlight Klinger's engagement with social critique and the darker, often brutal, realities hidden beneath the surface of bourgeois society. These print cycles demonstrate his commitment to using graphic art as a powerful tool for exploring complex, often uncomfortable, truths about humanity.

Symbolism and the Depths of the Psyche

Max Klinger is intrinsically linked to the Symbolist movement, which emerged across Europe in the late 19th century as a reaction against Realism and Impressionism. Symbolists sought to express subjective emotions, ideas, and spiritual values through suggestive imagery, metaphors, and allegorical figures, rather than depicting the objective, visible world. Klinger's work perfectly embodies this ethos.

His art is replete with symbolic figures and enigmatic scenarios that invite interpretation. He drew inspiration from classical mythology, biblical narratives, and contemporary philosophy, but always filtered these sources through his own unique, often unsettling, vision. His figures often seem caught between worlds – the real and the imagined, the conscious and the subconscious. This exploration of inner states and dreamlike realities connects him strongly to the psychological explorations that would characterize much of 20th-century art.

The influence of Arnold Böcklin, another major figure of Germanic Symbolism whom Klinger met and admired during his time in Rome, is palpable. Both artists shared an interest in mythological themes, a fascination with the mysterious and melancholic, and a tendency towards monumental, often dramatic compositions. However, Klinger's work often possesses a sharper, more psychologically intense edge, sometimes bordering on the grotesque or surreal. His ability to blend meticulous, almost photographic detail with utterly bizarre or fantastical subject matter creates a unique tension that remains compelling.

Journeys, Encounters, and Artistic Exchange

Klinger's artistic development was significantly shaped by his travels and interactions with other creative minds. His time spent in Paris exposed him to the powerful realism of Gustave Courbet and the more allegorical, classicizing style of Pierre Puvis de Chavannes. These encounters broadened his artistic horizons, allowing him to integrate different approaches into his own evolving style.

While in Paris, Klinger formed a friendship with the Swiss artist Karl Stauffer-Bern. This connection proved fruitful; Stauffer-Bern was an admirer of Klinger's graphic work and played a role in introducing it to others. Notably, he showed Klinger's prints to a young Käthe Kollwitz, who was profoundly impressed and inspired to pursue printmaking herself, becoming one of Germany's most important graphic artists, known for her powerful social commentary.

Klinger's network extended beyond visual artists. He developed a significant friendship with the composer Johannes Brahms. This connection facilitated an introduction to the influential Berlin music publisher Fritz Simrock, who became an important supporter, helping to publish and disseminate Klinger's print cycles, thereby increasing his visibility and impact. This interaction highlights the cross-pollination between music and visual arts prevalent in the era.

His time in Rome was also crucial, not only for the encounter with Böcklin but also for immersing himself in the art of antiquity and the Renaissance, which deeply informed his sculptural ambitions and his frequent engagement with classical themes. These periods abroad were not mere interludes but integral phases of absorption and synthesis in his artistic journey.

Monumental Ambitions: Klinger the Sculptor

While celebrated for his prints, Klinger harbored significant ambitions as a sculptor, viewing it as a medium capable of achieving monumental presence and enduring impact. He was drawn to the concept of the Gesamtkunstwerk, or total work of art, seeking to integrate different materials and artistic disciplines. This led him to embrace polychromy in sculpture – the use of various colored materials like different marbles, bronze, ivory, alabaster, and semi-precious stones within a single work. This practice challenged the Neoclassical preference for pure white marble established by figures like Antonio Canova and Bertel Thorvaldsen.

His sculptural masterpiece is undoubtedly the Beethoven Monument, completed in 1902 after years of work. Created for the XIV exhibition of the Vienna Secession, a movement Klinger was associated with, the sculpture was the centerpiece of an exhibition designed as a holistic tribute to the composer, featuring contributions from other Secession artists like Gustav Klimt (whose Beethoven Frieze was created for the same show).

Klinger's Beethoven is a striking and unconventional work. It depicts the composer enthroned like a classical deity, partially nude, carved from gleaming white marble. The throne itself is elaborate, made of bronze, ivory, and other materials, adorned with intricate reliefs depicting mythological and allegorical scenes related to Beethoven's music and genius, such as references to his opera Fidelio and his Ninth Symphony. An eagle, symbolizing divine inspiration or Jupiter, sits at his feet.

The sculpture was highly controversial. The nudity was deemed inappropriate by conservative critics, seen as disrespectful to the revered composer. The use of polychromy was also criticized for deviating from established sculptural norms. Yet, the work was hailed by progressive artists and critics as a powerful modern statement, a bold attempt to create a contemporary monument embodying the spirit of Beethoven's genius through a synthesis of materials and symbolic depth. It remains one of the most iconic works associated with the Vienna Secession and a testament to Klinger's audacious vision.

Other notable sculptures include The Judgment of Paris (1885-1887), another polychrome work tackling a classical theme with psychological nuance, and Christ in Olympus (1897), which provocatively places Christ within a pagan mythological setting. His sculpture Galatea, inspired by the Pygmalion myth, further demonstrates his engagement with classical forms and narratives, reinterpreted through his unique lens.

Painting and the Synthesis of Arts

Although printmaking and sculpture occupied much of his focus, Klinger continued to paint throughout his career. His paintings often share the thematic concerns and stylistic tendencies of his graphic work and sculptures. He explored mythological subjects, allegories, and landscapes imbued with symbolic meaning.

One of his well-known paintings is Die blaue Stunde (The Blue Hour), depicting a nude woman bathing by the sea at twilight. The work captures a mood of quiet introspection and connection with nature, rendered with a sensitivity to light and color that aligns it with Symbolist aesthetics. The use of color to evoke emotion and atmosphere is characteristic of his painted output.

Klinger's interest in the Gesamtkunstwerk extended to his approach across media. His sculptural thinking, particularly his fascination with different materials and textures, arguably influenced his handling of paint and tone. Conversely, the narrative and graphic sensibility honed in his printmaking informed the compositions and symbolic content of his paintings and sculptures. He sought a unity of artistic expression, where different media could complement and enrich one another in conveying his complex ideas.

Artistic Philosophy and Theoretical Contributions

Max Klinger was not only a prolific creator but also a thoughtful commentator on art. His essay "Malerei und Zeichnung" (1891) is a significant statement of his artistic philosophy, particularly regarding the distinct roles and potentials of painting and the graphic arts (which he termed Zeichnung, encompassing drawing and printmaking).

He argued that painting, with its reliance on color and connection to the tangible world, was best suited for representing reality and objective beauty. In contrast, he saw the graphic arts, particularly etching with its linear precision and capacity for stark tonal contrasts, as the ideal medium for exploring the subjective realm: fantasy, ideas, the subconscious, and the darker aspects of existence. The black and white nature of printmaking, he felt, lent itself to ambiguity and suggestion, allowing for a more direct expression of the artist's inner world.

This theoretical stance helps explain his dedication to print cycles as vehicles for his most personal and imaginative explorations, like the Glove series. By championing the expressive autonomy of graphic art, Klinger elevated its status and encouraged other artists, like Kollwitz, to embrace its potential. His ideas contributed to a broader re-evaluation of printmaking in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Jugendstil and the Vienna Secession: Engaging with Modern Movements

Klinger's career coincided with the rise of Art Nouveau, known as Jugendstil in Germany and Austria. While distinct from the purely decorative tendencies of some Jugendstil practitioners, Klinger's work shares certain characteristics with the movement, such as its emphasis on symbolism, its interest in integrating art into life, and sometimes its use of flowing, organic lines, particularly in decorative elements of his sculptures and prints. He is often considered a key figure bridging late 19th-century Symbolism and the emerging modern styles of the early 20th century.

His involvement with the Vienna Secession further cemented his position within the progressive art movements of the time. Founded in 1897 by artists like Gustav Klimt, Koloman Moser, and Josef Hoffmann, the Secession aimed to break away from the conservative artistic establishment, promote modern art, and foster a dialogue between different art forms (painting, sculpture, architecture, decorative arts).

Klinger was made an honorary member, and his Beethoven Monument became the focal point of their landmark 1902 exhibition. This event was conceived as a Gesamtkunstwerk itself, with artists collaborating to create a unified environment celebrating Beethoven. Klinger's participation underscored his alignment with the Secession's goals of artistic renewal and the synthesis of the arts. He also participated in other progressive initiatives, such as co-founding the "Group of XI" in Berlin with artists like Walter Leistikow and Ludwig von Hofmann (though the provided text mentions Stauffer-Bern, standard accounts usually list others for the Berlin Secession precursor group "XI"), which similarly sought to challenge the dominance of academic art institutions.

Later Life, Teaching, and Enduring Legacy

In his later years, Klinger continued to work, although perhaps with less of the radical innovation that marked his earlier career. He received numerous honors and held influential positions. He served as a professor at the Academy of Graphic Arts in Leipzig, passing on his technical knowledge and artistic philosophy to younger generations.

A significant aspect of his later life was his commitment to supporting fellow artists. In 1905, using funds from the sale of his Beethoven Monument (acquired by the city of Leipzig), he purchased the Villa Romana in Florence, Italy. He established it as a foundation providing studio space and stipends for promising German artists to live and work in Italy, fostering artistic development and cultural exchange. The Villa Romana remains an important institution for German artists to this day.

Max Klinger's influence extended well beyond his lifetime. His exploration of psychological themes, dream imagery, and the uncanny directly impacted Surrealists like Max Ernst and Salvador Dalí, who acknowledged his importance as a precursor. His intense emotional expression and symbolic depth resonated with Expressionists such as Edvard Munch. Artists like Alfred Kubin, known for his dark, fantastical drawings, also drew inspiration from Klinger's graphic work. Even artists moving towards abstraction, like Kasimir Malevich, were reportedly familiar with and potentially influenced by the conceptual power of Klinger's serial works. Käthe Kollwitz's debt to him is well-documented. His bold use of polychromy in sculpture also encouraged later artists to experiment with materials.

Klinger occupies a unique position in art history. He bridged the 19th and 20th centuries, connecting the traditions of Realism and Romanticism with the emerging currents of Symbolism, Jugendstil, and even proto-Surrealism. His mastery across painting, sculpture, and printmaking, combined with his theoretical insights and profound thematic explorations, marks him as a complex and highly significant figure.

Conclusion: A Visionary Across Media

Max Klinger was more than just a painter, sculptor, or printmaker; he was an artist-philosopher who used diverse media to explore the intricate tapestry of human experience. From the dreamlike anxieties of the Glove cycle to the monumental ambition of the Beethoven Monument, his work consistently pushed boundaries, challenging both artistic conventions and societal norms. He elevated graphic art to a major expressive form, pioneered the use of polychromy in modern sculpture, and delved into the subconscious with a visionary intensity that anticipated key developments in 20th-century art. His legacy lies not only in his powerful and often haunting images but also in his enduring influence on subsequent generations of artists who sought to express the hidden realities beneath the surface of the visible world. Max Klinger remains a vital figure for understanding the transition to modern art in Germany and beyond.