Gaston Bussière (1862-1928) stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the rich tapestry of late 19th and early 20th-century French art. A dedicated Symbolist painter and a prolific illustrator, Bussière carved a niche for himself by delving into the realms of mythology, literature, and the ethereal. His work, characterized by its dreamlike quality, meticulous detail, and often sensual portrayal of figures, captures the essence of the fin-de-siècle fascination with the unseen, the mystical, and the psychologically complex. While perhaps not as globally renowned today as some of his contemporaries, his contribution to Symbolism and book illustration remains a testament to a distinct artistic vision that resonated with the cultural currents of his time.

Early Life and Artistic Formation: From Lyon to the Parisian Epicenter

Born on April 24, 1862, in the quaint town of Cuisery, Saône-et-Loire, France, Gaston Bussière displayed an early inclination towards the arts. This nascent talent led him to pursue formal training, initially at the École des Beaux-Arts in Lyon. Lyon, a city with its own robust artistic traditions, provided him with a foundational understanding of academic principles. However, like many aspiring artists of his generation, the allure of Paris, the undisputed capital of the art world, proved irresistible.

Bussière subsequently enrolled at the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, the very heart of academic art training in France. Here, he had the invaluable opportunity to study under two highly respected and influential masters of the time: Alexandre Cabanel and Pierre Puvis de Chavannes. These two figures represented different, though not entirely incompatible, facets of the late 19th-century French art scene.

Alexandre Cabanel (1823-1889) was a quintessential academic painter, celebrated for his historical, classical, and religious subjects, executed with polished precision and a sensuous, idealized beauty. His most famous work, The Birth of Venus (1863), purchased by Napoleon III, epitomized the kind of art favored by the official Salons. Studying under Cabanel would have instilled in Bussière a strong command of draughtsmanship, anatomy, and the traditional techniques of oil painting.

Pierre Puvis de Chavannes (1824-1898), on the other hand, while also respected within the establishment, offered a different artistic path. Puvis was a master of large-scale mural painting, known for his simplified forms, muted color palettes, and serene, allegorical compositions that often evoked a timeless, almost dreamlike quality. Works like The Poor Fisherman (1881) or his murals for the Panthéon in Paris showcased a move away from strict academic realism towards a more synthetic and symbolic representation. Puvis's influence on Bussière can be seen in the younger artist's inclination towards allegorical themes and a certain poetic, otherworldly atmosphere in his paintings. His emphasis on decorative harmony and suggestive, rather than explicit, narratives resonated deeply with the burgeoning Symbolist movement.

This dual tutelage provided Bussière with a solid academic grounding from Cabanel, complemented by the more forward-looking, proto-Symbolist tendencies of Puvis de Chavannes. This blend would prove crucial in shaping his own artistic voice. In 1884, his talent received early recognition when he was awarded the Marie Bashkirtseff Prize, an accolade that would have bolstered his confidence and visibility as he embarked on his professional career.

The Emergence of a Symbolist Vision

The late 19th century was a period of profound cultural and intellectual ferment. Industrialization was reshaping society, scientific advancements were challenging old certainties, and a sense of spiritual unease pervaded many artistic and literary circles. As a reaction against the perceived materialism of Realism and the fleeting sensory impressions of Impressionism, Symbolism emerged as a potent artistic and literary movement. Symbolist artists sought to express subjective truths, emotions, and ideas through suggestive imagery, often drawing inspiration from dreams, mythology, religion, and literature.

Gaston Bussière was deeply attuned to these currents. His artistic sensibilities aligned perfectly with the Symbolist ethos, which prioritized the inner world over objective reality. He was particularly drawn to the evocative power of legends, epic poems, and dramatic narratives. The rich, often tragic, and emotionally charged stories found in the works of composers like Hector Berlioz and Richard Wagner, and writers like William Shakespeare, provided fertile ground for his imagination. Wagner's operas, with their grand mythological themes and exploration of love, death, and redemption, were a particularly potent source of inspiration for many Symbolists, and Bussière was no exception.

A pivotal artistic influence on Bussière, beyond his direct teachers, was Gustave Moreau (1826-1898). Moreau was a towering figure in Symbolist painting, revered for his opulent, jewel-like canvases depicting biblical and mythological scenes laden with complex symbolism and erotic undertones. Moreau's studio became a hub for a younger generation of artists, including future luminaries like Henri Matisse and Georges Rouault. While Bussière was not a direct pupil in the same way, Moreau's work, with its emphasis on intricate detail, rich textures, and enigmatic femmes fatales, undoubtedly left a significant mark on Bussière's own approach to Symbolist subject matter. The shared interest in exoticism, mysticism, and the power of the female figure is evident.

Bussière's paintings began to embody the key characteristics of Symbolism: a focus on mood and atmosphere, the use of symbols to convey deeper meanings, and a preference for subjects that transcended the mundane. His figures often appear ethereal, caught in moments of reverie, ecstasy, or despair, inhabiting landscapes that seem to belong more to the realm of dream than to the waking world.

Master of Illustration: Visualizing Literary Worlds

Beyond his easel paintings, Gaston Bussière achieved considerable renown as an illustrator. In an era when illustrated books were highly prized, his talent for translating the nuances of text into compelling visual imagery was much in demand. His Symbolist sensibility, with its emphasis on mood and suggestion, lent itself perfectly to the task of illuminating literary works, particularly those with romantic, fantastical, or decadent themes.

He created memorable illustrations for a diverse range of esteemed authors. Among his most notable commissions were illustrations for Honoré de Balzac's Les Contes drôlatiques (Droll Stories). These Rabelaisian tales, set in medieval France, offered ample scope for Bussière's imaginative flair and his ability to evoke a bygone era.

Théophile Gautier, a writer whose own work bridged Romanticism and Parnassianism and who was an early champion of "art for art's sake," was another author whose texts Bussière illustrated. Gautier's poetic and often exotic narratives provided a natural fit for Bussière's style. Specifically, his illustrations for Gautier's Émaux et Camées (Enamels and Cameos), a collection of exquisitely crafted poems, are highly regarded.

Perhaps one of his most famous series of illustrations was for Oscar Wilde's controversial and highly influential play, Salomé. Wilde's decadent and erotically charged retelling of the biblical story, famously illustrated by Aubrey Beardsley in England, also found a compelling interpreter in Bussière in France. Bussière's depictions of Salomé, the quintessential femme fatale, would have captured the play's atmosphere of obsession, desire, and impending doom, aligning with the Symbolist fascination for such powerful and often destructive female figures.

Gustave Flaubert, the master of French Realism but also an author whose works like Salammbô and The Temptation of Saint Anthony delved into historical exoticism and visionary experiences, also had his works illustrated by Bussière. This demonstrates Bussière's versatility and his ability to adapt his style to the specific demands of different literary genres while maintaining his characteristic Symbolist touch.

His illustrations were not mere literal translations of the text but rather evocative visual accompaniments that enhanced the reader's experience, adding another layer of interpretation and aesthetic pleasure. This body of work cemented his reputation and ensured his art reached a wider audience beyond the confines of art galleries.

Iconic Paintings and Predominant Themes

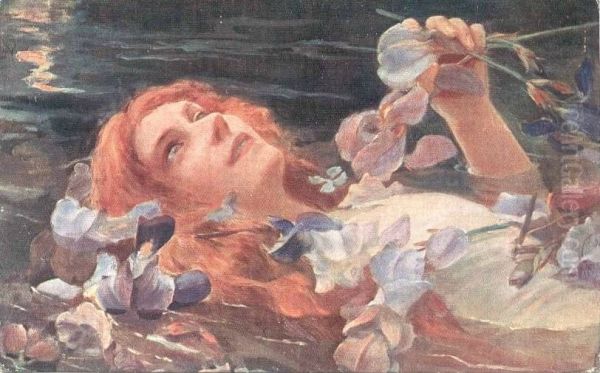

Gaston Bussière's painted oeuvre is rich with the themes central to Symbolism: mythology, legend, the spiritual, and the eternal feminine, often in her guise as the alluring and dangerous femme fatale. His works frequently explore narratives of tragic love, heroic sacrifice, and mystical encounters.

One of his celebrated paintings is Isolde (also known as The Death of Isolde), created around 1911. This work draws from the medieval legend of Tristan and Isolde, a tale of adulterous love and tragic destiny popularized in the 19th century, not least by Richard Wagner's opera Tristan und Isolde. Bussière's depiction likely focuses on the emotional intensity and romantic doom inherent in the story, portraying Isolde in a moment of profound grief or mystical transfiguration. The rendering would emphasize her beauty, sorrow, and the almost sacred nature of her love, all hallmarks of Symbolist interpretations of such legends.

Another significant piece is Brunhilde (or Brünnhilde), painted around 1923. This subject, drawn from Norse mythology and, again, famously central to Wagner's Ring Cycle (Der Ring des Nibelungen), depicts the powerful Valkyrie. Bussière's interpretation would likely highlight Brunhilde's heroic stature, her tragic fate, and perhaps the conflict between her divine nature and her human emotions. Such a subject allowed for dramatic compositions and the exploration of themes of destiny, betrayal, and sacrifice. He also painted other scenes from the Ring Cycle, such as Wotan bidding farewell to Brunhilde.

The Queen with Golden Hair (circa 1920), an oil on canvas, is another example of his focus on idealized and enigmatic female figures. The title itself evokes a sense of fairytale or legend. The painting likely portrays a woman of regal bearing and captivating beauty, her golden hair perhaps symbolizing purity, divinity, or an almost magical allure. Such works often hovered between portraiture and allegorical representation, imbuing the subject with a timeless, iconic quality.

Bussière also explored Celtic legends, including themes from the Arthurian cycle, such as the story of Merlin and Vivien. His interest extended to French epic poetry, notably The Song of Roland. These choices reflect a broader Romantic and Symbolist fascination with national myths and medieval lore, seen as repositories of spiritual truth and heroic ideals.

A somewhat different but equally symbolic work is The Allegory of White Coal (circa 1901). "White coal" (houille blanche) is a French term for hydroelectric power. This painting likely personifies this modern energy source in a classical or mythological guise, perhaps as a nymph or a powerful deity, thus ennobling a product of industrial progress through the lens of timeless allegory. This demonstrates an interesting intersection of Symbolist aesthetics with contemporary themes, praising the "natural" power of water in contrast to the "black coal" of heavy industry.

His female figures often embody the femme fatale archetype – seductive, mysterious, and potentially destructive. Whether Salomé, sirens, or mythological enchantresses, these women represent both the allure and the perceived danger of female sexuality, a common preoccupation in fin-de-siècle art and literature, explored by artists like Gustave Moreau, Franz von Stuck, and Edvard Munch.

The Rose+Croix Salons and the Esoteric Milieu

A significant aspect of Bussière's career was his association with the Salon de la Rose+Croix. Founded by the eccentric writer and mystic Joséphin Péladan in 1892, these Salons were conceived as an antidote to the perceived materialism and lack of spiritual depth in mainstream art. Péladan, a self-styled Sâr (a Chaldean title for "chief"), aimed to promote an art that was idealistic, mystical, and legendary, explicitly rejecting realism, history painting of a mundane sort, and Impressionism.

The Rose+Croix Salons became a prominent venue for Symbolist artists from across Europe. They showcased works that emphasized themes of spirituality, myth, dream, and the occult. The atmosphere was one of esoteric idealism, often with a strong Catholic or neo-Platonic underpinning. Gaston Bussière exhibited at these Salons, placing him firmly within this circle of artists who sought to imbue their work with a higher, spiritual purpose.

Other artists who exhibited at the Rose+Croix Salons included prominent Symbolists such as the Belgian painters Fernand Khnopff and Jean Delville, the Swiss artist Carlos Schwabe (who designed the iconic poster for the first Salon), and French artists like Antoine Bourdelle (in his early Symbolist phase) and Edmond Aman-Jean. The Salons were influential in defining and promoting a certain strand of Symbolism, one that was overtly spiritual and often anti-modernist in its rejection of contemporary life as a primary subject. Bussière's participation underscores his commitment to the ideals of Symbolist art and his connection to its more esoteric and mystical currents.

Beyond the Canvas: Ventures into Decorative Arts

Like many artists associated with the Art Nouveau movement, which overlapped chronologically and thematically with Symbolism, Gaston Bussière did not confine his talents solely to painting and illustration. He also ventured into the realm of decorative arts. This was in keeping with the Art Nouveau ideal of the Gesamtkunstwerk (total work of art), which sought to break down the traditional hierarchy between fine arts (painting, sculpture) and applied arts.

Bussière is known to have designed patterns for ceramics, stained glass windows, and textiles. This expansion into decorative media allowed him to bring his distinctive visual language to a wider range of objects and environments. His Symbolist motifs – sinuous lines, organic forms, mythological figures, and dreamlike imagery – would have translated well into these formats.

His work in stained glass, for instance, would have allowed him to explore the interplay of light and color in a manner akin to medieval craftsmanship, a period often romanticized by Symbolists. Ceramic designs could have featured his characteristic figures and decorative patterns, while textile designs might have incorporated flowing, nature-inspired motifs.

This engagement with decorative arts connects Bussière to other artists of the period who similarly embraced a broader definition of artistic practice, such as Alphonse Mucha, renowned for his posters and decorative panels, or Gustav Klimt in Vienna, whose work seamlessly blended painting with decorative elements and who was a key figure in the Vienna Secession, which also advocated for the integration of arts and crafts. Bussière's involvement in these areas highlights his versatility and his participation in the broader aesthetic trends of the fin-de-siècle that sought to infuse everyday objects with artistic beauty and symbolic meaning.

Artistic Techniques and Mediums

Gaston Bussière was proficient in a variety of artistic mediums, which allowed him to achieve different effects and cater to diverse commissions. His primary medium for major Salon paintings was oil on canvas, the traditional choice for ambitious academic and Symbolist works. His oil paintings are characterized by a refined technique, careful attention to detail, and a rich, often jewel-like, color palette that could evoke the opulence of his subjects or the somber mood of a tragic scene. He demonstrated a mastery of light and shadow (chiaroscuro), using it to model his figures, create dramatic emphasis, and enhance the mysterious atmosphere of his compositions.

In addition to oils, Bussière frequently worked in watercolor. This medium, with its potential for translucency and delicate washes, was well-suited to his more ethereal and dreamlike subjects. Watercolors allowed for a lighter touch and could be used effectively for preparatory studies or for finished works intended for illustration or private collection.

Pastels were another medium he employed. Pastels offer a unique combination of painterly and graphic qualities, allowing for both soft, blended tones and crisp lines. The vibrant, powdery pigments of pastels could achieve a luminous, velvety texture, ideal for capturing the sensual qualities of flesh or the shimmering surfaces of fabrics and mythical landscapes. Artists like Odilon Redon, another key Symbolist figure, also famously exploited the evocative potential of pastels for his visionary works.

His skill as a draughtsman, honed during his academic training, underpinned all his work, whether in painting or illustration. Strong drawing was essential for defining the elegant contours of his figures and for structuring his often complex compositions. This technical versatility enabled Bussière to fully realize his imaginative visions across different formats and for different purposes.

Bussière and His Contemporaries: A Web of Influences

Gaston Bussière operated within a vibrant and complex artistic milieu. His teachers, Alexandre Cabanel and Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, provided him with foundational, albeit differing, artistic philosophies. Cabanel represented the polished academic tradition, a style also championed by contemporaries like William-Adolphe Bouguereau, whose technically flawless and often sentimental depictions of mythological and allegorical scenes were immensely popular.

Puvis de Chavannes, however, pointed towards a more simplified, decorative, and symbolic approach, influencing not only Bussière but also artists like Maurice Denis and other members of the Nabis group, who admired his emphasis on flat planes of color and rhythmic composition.

The most profound artistic kinship for Bussière was undoubtedly with Gustave Moreau. Moreau's influence on the Symbolist generation was immense, and Bussière's work shares Moreau's fascination with exotic detail, complex allegories, and the potent figure of the femme fatale. Other Symbolists exploring similar thematic territory included the Belgian artist Fernand Khnopff, known for his enigmatic and psychologically charged images, often centered on sphinxes and idealized female figures. Jean Delville, another Belgian, created overtly esoteric and mystical paintings, often with a Theosophical bent.

In Switzerland, Arnold Böcklin painted haunting mythological landscapes and scenes, such as his famous Isle of the Dead, which resonated deeply with the Symbolist mood of melancholy and introspection. In Germany, Franz von Stuck explored dark, sensual, and often disturbing mythological themes, his work bordering on a more decadent and overtly erotic form of Symbolism.

While Bussière's style was distinct, it existed in dialogue with these and other artists. For instance, the dreamlike quality in some of his works might find parallels in the visionary art of Odilon Redon, though Redon's imagery often veered into more surreal and fantastical territories. The decorative elegance present in Bussière's work, especially in his illustrations and designs, also connects him to the broader Art Nouveau movement, with figures like Alphonse Mucha in Paris or Gustav Klimt in Vienna, who similarly embraced sinuous lines and stylized natural forms.

Even artists who took different paths, like Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, who documented the gritty reality of Parisian nightlife, were part of the same fin-de-siècle cultural landscape, a period characterized by a search for new forms of expression and a questioning of established norms. Bussière's contribution was to champion the imaginative and the mystical within this diverse artistic environment.

Untimely End, Legacy, and Collections

Gaston Bussière's productive career was cut short. He died on October 29, 1928 (some sources cite 1929, but 1928 is more commonly accepted by art historical records), reportedly as the result of a car accident. He was 66 years old. Despite his relatively early death, he left behind a substantial body of work that continues to be appreciated by those interested in Symbolist art and late 19th-century illustration.

His works are preserved in various public and private collections. Notably, the Musée des Ursulines in Mâcon, a city in his native Burgundy region, holds a significant collection of his paintings, making it an important center for the study of his art. Other museums in France may also hold examples of his work. His illustrations, by their nature, are found within the pages of the books he adorned, many of which are now collectors' items.

While Gaston Bussière may not command the same level of international fame or astronomical auction prices as some of his contemporaries like Gustav Klimt or Edvard Munch, or even later figures like Jean-Michel Basquiat whose market performance is often cited in contemporary art discussions, his work holds a secure place within the narrative of French Symbolism. He is valued for his technical skill, his imaginative interpretations of literary and mythological themes, and his consistent dedication to a Symbolist aesthetic.

His art provides a window into the fin-de-siècle mindset, with its anxieties, its yearning for beauty and spirituality, and its fascination with the mysterious and the erotic. For scholars and enthusiasts of Symbolism, Bussière remains an important figure whose contributions enrich our understanding of this multifaceted artistic movement.

The Enduring Allure of Bussière's Art

The art of Gaston Bussière continues to exert a subtle allure. In a world often dominated by the literal and the overt, his paintings and illustrations offer an escape into realms of dream, myth, and poetic suggestion. His meticulously rendered figures, whether they be tragic heroines, ethereal nymphs, or powerful goddesses, speak to a timeless fascination with storytelling and the power of the human imagination.

His commitment to beauty, even when exploring themes of tragedy or melancholy, aligns with a core tenet of much Symbolist art: the belief in art's capacity to transcend the mundane and offer a glimpse of a higher, more meaningful reality. The sensuousness of his figures, the richness of his colors, and the often-intricate details of his compositions invite close looking and contemplation.

While the grand narratives of mythology and legend that so inspired Bussière may not hold the same central place in contemporary culture as they did in the late 19th century, his work reminds us of their enduring power to explore fundamental human emotions and experiences: love, loss, desire, heroism, and the search for meaning. As an artist who dedicated his career to visualizing these profound themes with skill and imagination, Gaston Bussière's legacy is one of quiet distinction, a valuable contributor to the rich and diverse landscape of French art at the turn of the century. His art remains a testament to an era that valued the unseen worlds as much, if not more, than the visible one.