Hieronymus Bosch, a pivotal figure straddling the late Gothic and early Renaissance periods in Northern Europe, remains one of art history's most fascinating and perplexing artists. Active roughly between 1470 and his death in 1516, Bosch crafted a unique visual language filled with fantastical creatures, nightmarish landscapes, and profound moral allegories. His work delves deep into the anxieties and beliefs of his time, exploring themes of sin, redemption, folly, and the eternal struggle between good and evil. Though details of his life are scarce, his surviving paintings and drawings offer a window into a mind both deeply rooted in medieval tradition and astonishingly prescient of modern psychological explorations.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in 's-Hertogenbosch

Born Jheronimus van Aken around 1450, the artist later adopted the name "Bosch" from his hometown, 's-Hertogenbosch, often colloquially called Den Bosch ("The Forest"). This prosperous ducal town in Brabant, now part of the Netherlands, was the center of his world. He hailed from a family of artists; both his grandfather, Jan van Aken, and his father, Anthonius van Aken, were painters, originally from Aachen (Aken in Dutch). This familial background strongly suggests that Hieronymus received his initial artistic training within the family workshop, absorbing the craft traditions passed down through generations.

Life in 's-Hertogenbosch was not without its turmoil. Historical records point to a devastating fire in 1463 that ravaged a large part of the town, reportedly destroying thousands of houses, including potentially the van Aken family home. Some scholars speculate that the recurring motifs of fire, destruction, and chaos in Bosch's later works, particularly his depictions of Hell, might reflect the traumatic impact of this early experience. Witnessing such widespread calamity could have deeply impressed upon the young artist the fragility of life and the omnipresence of potential disaster, themes echoed in his mature art.

Unlike many prominent artists of the Renaissance who traveled extensively, particularly to Italy, Bosch appears to have spent the vast majority of his life and career within the confines of 's-Hertogenbosch and its immediate surroundings. This relative geographic isolation may have contributed to the highly individualistic and idiosyncratic nature of his art. Shielded from the direct, overwhelming influence of the burgeoning Italian Renaissance styles exemplified by artists like Leonardo da Vinci or Raphael, Bosch developed a visual vocabulary that was distinctly Northern European, yet uniquely his own.

The Artist and His City: Faith and Community

Despite the often disturbing and seemingly heretical imagery in his paintings, evidence suggests Bosch was a respected member of his community and a devout Catholic. He became a member of the Illustrious Brotherhood of Our Blessed Lady (Illustre Lieve Vrouwe Broederschap), a prestigious religious confraternity based at the imposing St. John's Cathedral in 's-Hertogenbosch. This group included influential members of local society, both clergy and laity. Bosch's involvement went beyond mere membership; records indicate he received commissions from the Brotherhood, contributing to the artistic embellishment of their chapel.

His marriage around 1480 to Aleyt Goyaerts van den Meerveen, who came from a wealthy family, likely elevated his social standing and provided financial stability. This allowed him a degree of artistic freedom, perhaps enabling him to pursue his more unconventional visions without constant pressure for purely commercial or conventional religious commissions. His deep engagement with religious themes, however, remained central. His works consistently grapple with Christian doctrine, particularly concerning sin, judgment, and the afterlife, suggesting a profound, if complex, personal faith.

His standing within the community is further attested by the fact that upon his death in August 1516, he was buried with honors in the St. John's Cathedral, the very church intertwined with his life and faith through the Brotherhood. This context positions Bosch not as a fringe eccentric, but as an integrated, albeit highly imaginative, member of late medieval society, using his art to explore its deepest spiritual and moral concerns.

Hallmarks of Bosch's Unmistakable Style

Bosch's art is immediately recognizable for its unique blend of meticulous realism in detail and wildly imaginative, often grotesque, subject matter. He populated his canvases with a bizarre menagerie of hybrid creatures, demonic figures, and distorted human forms engaged in acts of sin or suffering bizarre torments. These fantastical elements are not mere whimsy; they function as complex symbols, drawing on medieval bestiaries, folklore, proverbs, and religious allegory to convey moral lessons or comment on human nature.

His paintings often feature panoramic landscapes teeming with activity, demanding close inspection to decipher the myriad narratives unfolding within. He employed a vibrant color palette and precise brushwork, characteristic of the Northern Renaissance tradition inherited from masters like Jan van Eyck. However, Bosch pushed the boundaries of this tradition, using his technical skill to render the unreal utterly convincing. Heaven, Earth, and Hell are depicted with equal intensity and detail, blurring the lines between the sacred, the profane, and the fantastical.

A key characteristic is his exploration of the human psyche, particularly its darker aspects: temptation, lust, greed, folly, and the consequences of succumbing to sin. His depictions of Hell are particularly inventive and terrifying, filled with elaborate tortures often related symbolically to the sins being punished. Yet, even his portrayals of earthly life or paradise are often tinged with ambiguity and a sense of impending doom, suggesting a pessimistic view of humanity's capacity for corruption.

Major Masterpieces: Visions of Heaven, Hell, and Humanity

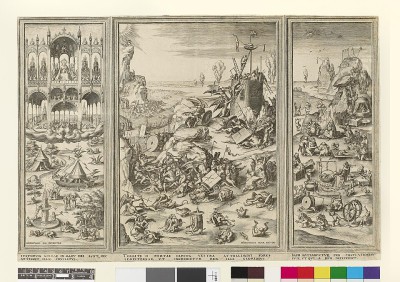

Among Bosch's surviving works, several stand out as iconic representations of his unique vision. Perhaps the most famous is The Garden of Earthly Delights (c. 1490-1510), a large triptych housed in the Prado Museum, Madrid. The left panel depicts the Garden of Eden, showing the creation of Eve and the moments before the Fall. The central panel, the "garden" itself, is a riotous scene of naked figures cavorting amidst oversized fruits, birds, and strange structures – often interpreted as a depiction of humanity indulging in worldly, sinful pleasures. The right panel presents a terrifying, surreal vision of Hell, where sinners endure punishments tailored to their transgressions, orchestrated by monstrous demons. Its exact meaning remains debated, but it stands as a powerful allegory of temptation, sin, and damnation.

Another significant triptych is The Temptation of St. Anthony (c. 1480-1510), existing in several versions, with the primary one likely being in Lisbon. This work focuses on the trials of the desert hermit St. Anthony, besieged by demonic apparitions and temptations. Bosch uses the saint's ordeal as a canvas to unleash an astonishing array of grotesque creatures and hallucinatory scenes, symbolizing the internal and external struggles against evil and doubt. The painting explores themes of faith, endurance, and the pervasive nature of temptation in the world.

The Last Judgment (c. 1505), with a notable version in Vienna, tackles a traditional Christian theme but infuses it with Bosch's characteristic nightmarish imagery. It depicts Christ presiding over the judgment of souls, with angels guiding the saved towards a serene Heaven while demons drag the damned into a chaotic and fiery Hell. The inventiveness of the tortures and the sheer density of symbolic detail make Bosch's interpretation particularly powerful and unsettling, serving as a stark moral warning to the viewer.

The painting known as The Seven Deadly Sins and the Four Last Things (c. 1500), presented in a unique tabletop format, offers a more didactic approach. The central circle depicts the eye of God, with Christ at the pupil, observing scenes representing the seven deadly sins (pride, envy, anger, sloth, greed, gluttony, lust) arranged in a circle. The four corners illustrate the "Four Last Things": Death, Judgment, Heaven, and Hell. This work functions as a clear moral compass, reminding viewers of divine omniscience and the ultimate consequences of their actions.

Other notable works further showcase Bosch's thematic range and stylistic innovations. Death and the Miser portrays the struggle for a dying man's soul between an angel and a demon, highlighting the sin of avarice. The Conjurer (or The Magician) depicts a scene of street trickery and pickpocketing, commenting on human gullibility and deception. The Adoration of the Magi, while a more conventional religious subject, is rendered with Bosch's typical attention to detail and includes subtle, potentially ominous elements in the background, characteristic of his complex worldview.

Sources, Influences, and Interpretations

Deciphering the exact meaning and sources behind Bosch's complex imagery remains a significant challenge for art historians. His work clearly draws from the rich visual and textual traditions of the late Middle Ages. Biblical narratives, lives of saints (like St. Anthony), and apocalyptic literature provide foundational themes. However, he also seems to incorporate elements from contemporary folklore, Dutch proverbs, moralizing literature, and possibly even practices like alchemy and astrology, though direct evidence for the latter remains speculative and debated.

Some scholars have proposed that Bosch might have been affiliated with esoteric or heretical groups, such as the Adamites or Cathars, citing the seemingly anti-clerical or Gnostic undertones in some works. However, his documented membership in the orthodox Brotherhood of Our Lady and the prevalence of traditional Christian morality in his paintings make such interpretations contentious. Most mainstream scholarship now views Bosch as a deeply religious, albeit highly unconventional, moralist, using his art to critique the sins and follies he observed in the world around him, perhaps reflecting the anxieties of a society on the cusp of the Reformation.

The ambiguity inherent in his symbolism allows for multiple layers of interpretation, which may have been intentional. His patrons, who included members of the nobility like Philip the Handsome and Margaret of Austria, as well as religious institutions, likely appreciated the intellectual and visual complexity of his work. The enduring fascination with Bosch lies partly in this interpretive openness, allowing each generation to find new relevance in his visions of human nature and the cosmos.

Bosch and His Contemporaries: Isolation and Influence

While Bosch worked during a period of intense artistic activity across Europe, documented evidence of direct personal interaction with other major painters is scarce. His presumed lifelong residency in 's-Hertogenbosch limited his opportunities for direct exchange with artists in Flanders, Germany, or Italy. There's no record of him meeting giants of the Italian High Renaissance like Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, or Raphael, nor German masters like Albrecht Dürer. While some scholars have tentatively suggested possible links or indirect influences, perhaps via prints or travel to nearby regions, or even a hypothetical trip to Venice influencing artists like Giorgione, these remain largely unproven.

However, Bosch's impact on subsequent generations, particularly in Northern Europe, was profound. His most significant artistic heir was undoubtedly Pieter Bruegel the Elder (c. 1525-1569). Bruegel, working several decades after Bosch's death, clearly studied and absorbed Bosch's style and thematic concerns. Bruegel's own depictions of peasant life, proverbs, and religious allegories, including his famous Hell scenes like Dulle Griet (Mad Meg) and The Fall of the Rebel Angels, show a clear debt to Bosch's imaginative power and compositional strategies. Bruegel was even nicknamed "the second Bosch" or "Peasant Bosch," highlighting this strong artistic lineage.

Bosch's influence extended beyond Bruegel. His workshop likely produced numerous paintings in his style, and countless imitators emerged throughout the 16th century, capitalizing on the popularity of his demonic and fantastical imagery. Though he didn't establish a formal 'school' in the Italian sense, his unique vision permeated Netherlandish art for decades after his death, disseminated partly through prints made after his designs.

The Workshop, Attribution, and Scholarly Debates

One of the major ongoing challenges in Bosch scholarship is the question of attribution. Only about 25 paintings and a similar number of drawings are now confidently attributed to Bosch himself. His style was so popular and widely imitated, both during his lifetime by workshop assistants and afterwards by other artists, that distinguishing the master's hand from that of his followers is extremely difficult. For centuries, many works were incorrectly assigned to Bosch.

Recent decades have seen significant advances thanks to scientific methods. The Bosch Research and Conservation Project (BRCP), initiated in the Netherlands, has employed techniques like infrared reflectography (IRR), dendrochronology (wood panel dating), and pigment analysis to study the underdrawings, materials, and construction of paintings associated with Bosch. Their findings, published around the 500th anniversary of Bosch's death in 2016, led to several reattributions, sometimes controversially removing works long considered autograph from the master's oeuvre, while occasionally adding others.

These technical studies have shed light on Bosch's working methods, revealing complex underdrawings and sophisticated layering techniques, often using egg tempera alongside oil paints. They also highlight the likely role of a workshop in producing variations or versions of popular compositions. However, scholarly consensus is not always achieved. For instance, differing opinions exist between research groups like BRCP and individual experts like Fritz Koreny regarding the extent of workshop participation versus the master's direct involvement, particularly concerning the drawings. These debates underscore the complexities of studying an artist whose life is poorly documented but whose work had such a wide impact.

Enduring Mysteries and Unanswered Questions

Despite advances in research, Hieronymus Bosch remains shrouded in mystery. We lack personal letters, diaries, or theoretical writings that might explain his intentions or the specific meanings behind his bewildering symbols. Details about his education, the exact nature of his training beyond the family workshop, and the full range of his patrons remain elusive. Why did he develop such a unique and often disturbing style? Was he primarily a stern moralist, a satirist, a commentator on social upheaval, or something else entirely?

Even his death and burial hold enigmatic elements. While records confirm his burial in St. John's Cathedral, a peculiar story emerged, mentioned in the user's provided text, concerning an excavation of his presumed grave site in 1977 which allegedly found it empty, with unusual material reactions noted on the tombstone. While such accounts often border on the sensational and require rigorous verification, they contribute to the aura of mystery surrounding the artist. The lack of definitive answers to fundamental questions about his life and work continues to fuel speculation and research.

His unique vision, seemingly emerging with little precedent and leaving a powerful but often imitated legacy, makes him a perennial puzzle. Was he a product of late medieval anxieties, a harbinger of Renaissance individualism, or perhaps both? The enduring power of his art lies precisely in its ability to provoke these questions and resist easy categorization.

Legacy and Influence Through the Centuries

Hieronymus Bosch's influence, though perhaps initially concentrated in the Netherlands through followers like Pieter Bruegel the Elder, proved remarkably persistent and resurfaced powerfully centuries later. After a period of relative obscurity, his work gained renewed appreciation in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The rise of psychology and interest in the subconscious resonated with Bosch's explorations of dreams, nightmares, and the irrational.

He became a crucial figure for the Surrealist movement in the 1920s and 1930s. Artists like Salvador Dalí, Max Ernst, and René Magritte saw in Bosch a spiritual ancestor, a painter who had dared to depict the landscapes of the mind long before Freud. Dalí's melting clocks and fantastical creatures, Ernst's frottage and decalcomania techniques generating bizarre forms, and Magritte's juxtapositions of ordinary objects in extraordinary contexts all echo, in different ways, Bosch's pioneering journey into the surreal. Even Pablo Picasso, though stylistically distant, represents the kind of radical artistic innovation that Bosch embodied in his own time.

Bosch's influence wasn't limited to Surrealism. His dark, often satirical, visions of humanity can be seen as precursors to later artists who explored social critique and the grotesque, such as Francisco Goya in his "Black Paintings" and Disasters of War series. In contemporary culture, Bosch's imagery continues to inspire filmmakers, writers, musicians, and game designers, his hellscapes and hybrid monsters finding new life in fantasy genres and explorations of the macabre. His work demonstrates that the anxieties and fascinations of the late medieval world can still speak powerfully to modern audiences.

Conclusion: The Timeless Enigma

Hieronymus Bosch occupies a unique and pivotal place in Western art. Rooted in the religious and cultural milieu of the late Middle Ages, he simultaneously transcended its conventions with an imaginative power that seems almost modern. His paintings are intricate puzzles, moral warnings, and psychological landscapes rolled into one. They confront viewers with the complexities of human nature – our capacity for both profound faith and abject sin, for reason and utter folly.

While scholarship continues to unravel aspects of his technique, context, and the meaning of his symbols, the core enigma of Bosch remains. He was a master craftsman, a visual storyteller of unparalleled originality, and a profound commentator on the human condition. His ability to blend the real and the fantastic, the sacred and the profane, the terrifying and the strangely humorous, ensures his enduring relevance. The world he created, teeming with bizarre creatures and profound allegories, continues to fascinate, disturb, and provoke thought, securing his legacy as one of art history's most compelling and mysterious figures.