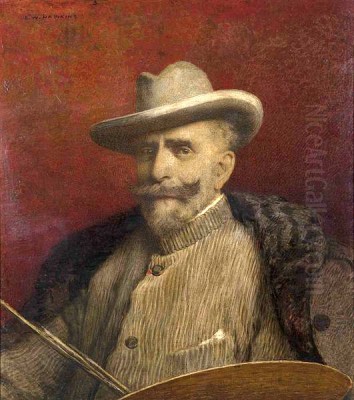

Louis Welden Hawkins stands as a fascinating figure in the landscape of late nineteenth-century European art. Primarily associated with the French Symbolist movement, his life and work reflect a unique blend of cultural influences, artistic sensibilities, and social engagement. Born into a world of mixed European aristocracy, he ultimately found his artistic home in Paris, contributing a distinct voice characterized by delicate aesthetics, mystical undertones, and a profound interest in the human, particularly the female, form. His journey from a potential naval career to becoming a recognized painter, collected by major museums, reveals an artist navigating the complex currents of his time.

A Transnational Heritage and Parisian Formation

The origins of Louis Welden Hawkins were notably cosmopolitan. He was born on July 1, 1849, not in France or Britain, the nations most associated with his career, but in Essingen, near Stuttgart, Germany. His parentage immediately set him apart: his father was a British naval officer, while his mother hailed from Austrian nobility, a Baroness von Welden. This mixed heritage perhaps prefigured the artist's later ability to absorb and synthesize diverse influences. Though born in Germany, Hawkins spent his formative years primarily in London.

Initially, it seemed Hawkins might follow his father's path. He briefly joined the British Royal Navy, an experience that suggests an early life oriented towards convention and duty. However, the call of art proved stronger. Around the age of fifteen, he made the decisive choice to abandon his naval prospects and dedicate himself to painting. This pivotal decision led him, like so many aspiring artists of his generation, to Paris, the undisputed capital of the art world. He is believed to have settled there around 1870.

In Paris, Hawkins sought formal training at the prestigious Académie Julian. This independent art school was a vital hub for both French and international students, offering an alternative to the more rigid École des Beaux-Arts. At the Académie Julian, Hawkins studied under respected academic painters such as Jules Joseph Lefebvre and William-Adolphe Bouguereau. While these masters represented a more traditional, polished style, their emphasis on technical skill, particularly in figure drawing and painting, provided Hawkins with a solid foundation upon which he would later build his more personal and Symbolist-inflected art. His time at the Académie Julian immersed him in the vibrant, competitive, and intellectually stimulating environment of the Parisian art scene.

A significant step in affirming his connection to his adopted country came much later in his career. In 1895, Louis Welden Hawkins formally obtained French citizenship. This act solidified his identity as a French artist, despite his British and Austro-German roots, and aligned him officially with the nation where his artistic reputation was forged.

Embracing Symbolism

Hawkins's emergence as a notable artist coincided with the rise of Symbolism in France during the latter decades of the nineteenth century. This movement, arising partly as a reaction against the perceived objectivity of Realism and the fleeting sensory focus of Impressionism, sought to explore inner worlds, dreams, emotions, and mystical ideas. Symbolist artists favoured suggestion over description, using symbols, metaphors, and allegories to convey complex psychological states and spiritual concepts. Hawkins found a natural affinity with this artistic current.

His official debut on the Parisian art stage occurred in 1881, when he exhibited for the first time at the influential Salon de la Société des Artistes Français. This annual exhibition was a crucial venue for artists seeking recognition and patronage. Hawkins's participation marked his entry into the professional art world, and he continued to exhibit there and at other significant venues, such as the Salon de la Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts (associated with figures like Auguste Rodin and Puvis de Chavannes) and the Salons de la Rose+Croix, organized by the eccentric Sâr Péladan, which were showcases for esoteric and Symbolist art.

Hawkins's work increasingly aligned with Symbolist aesthetics. He moved away from purely naturalistic representation towards compositions imbued with atmosphere, mystery, and symbolic weight. His paintings often feature figures that seem detached from the everyday world, inhabiting realms of thought, dream, or spiritual contemplation. He employed a refined technique, often characterized by smooth surfaces, delicate colour harmonies, and meticulous attention to detail, which served to enhance the otherworldly or idealized quality of his subjects. Unlike some Symbolists who delved into darker, more decadent themes, Hawkins often maintained a sense of grace and elegance, though hints of melancholy or enigmatic meaning were rarely absent.

Artistic Style: Elegance, Mystery, and Social Conscience

The art of Louis Welden Hawkins is characterized by several distinct features that define his unique position within the Symbolist movement and the broader context of fin-de-siècle art. His style represents a confluence of influences, blending Symbolist ideals with elements drawn from other contemporary trends and personal preoccupations.

Symbolist Aesthetics and Mysticism: At its core, Hawkins's art is Symbolist. He utilized visual language to hint at meanings beyond the surface appearance. His works often evoke moods of introspection, reverie, or quiet solemnity. Mystical and sometimes esoteric themes appear, reflecting the era's fascination with the unseen, the spiritual, and the occult. This can be seen in his choice of subject matter, such as allegorical figures or scenes suggesting spiritual journeys, like The Procession of Souls. He employed symbols – sometimes personal, sometimes drawn from broader cultural traditions – to enrich the narrative and emotional resonance of his paintings, inviting viewers to interpret rather than simply observe. Gothic motifs and a sense of the medieval past, filtered through a late-nineteenth-century lens similar to the Pre-Raphaelites like Dante Gabriel Rossetti or Edward Burne-Jones, also occasionally surface in his work.

The Delicate Female Portrait: Hawkins gained particular renown for his depictions of women. His female figures are typically portrayed with an air of refinement, sensitivity, and often a touch of melancholic grace. They are not merely realistic likenesses but idealized representations, often appearing lost in thought or embodying abstract concepts. His technique in these portraits is exceptionally delicate, with careful modelling of features, subtle use of light and shadow, and often rich, decorative backgrounds that contribute to the overall dreamlike effect. These portraits stand in contrast to the more robust or overtly sensual depictions of women by some contemporaries, offering instead a vision of femininity intertwined with introspection and ethereal beauty. His approach resonates with the work of other Symbolists focused on the enigmatic female form, such as Fernand Khnopff.

Fusion with Naturalism and Impressionism: While firmly rooted in Symbolism, Hawkins's style was not entirely detached from other artistic developments. Elements of Naturalism, likely absorbed during his academic training, are visible in the careful rendering of figures and textures. More subtly, the influence of Impressionism can sometimes be detected, particularly in his handling of light and atmosphere, especially in his landscape paintings from later in his career. He demonstrated an ability to capture nuanced effects of light, transforming ordinary scenes into something more evocative and mysterious, as seen in Le Foyer (Home). This blending of precise rendering with atmospheric effects distinguishes his work from both purely academic painting and the looser brushwork of mainstream Impressionists like Claude Monet or Camille Pissarro.

Exploration of the Fantastical and Hybrid Creatures: Hawkins displayed a marked interest in mythological and fantastical themes, including the depiction of hybrid creatures. His painting The Sphinx and the Chimera (Le Sphinx et la Chimère) is a prime example, bringing together two potent symbols from ancient mythology known for their enigmatic and monstrous qualities. This interest in the bizarre and the mythical aligns him with other Symbolists like Gustave Moreau or Odilon Redon, who explored the realms of legend, dream, and the subconscious. These works allowed Hawkins to delve into themes of duality, the unknown, and the complex, sometimes unsettling, aspects of the human psyche.

Social and Political Dimensions: Beyond purely aesthetic concerns, Hawkins's art and life were connected to the social and political currents of his time. He maintained connections with individuals involved in radical socialist and anarchist circles, such as the writer and activist Séverine (Caroline Rémy de Guebhard), whom he famously painted. His association with figures like Pierre-Carlet de la Chataigneraie (known as Capelétan) further indicates his engagement with progressive, and sometimes controversial, social ideas. While his paintings are rarely overtly political, his choice of subjects, like the portrait of the humanitarian and anti-establishment journalist Séverine, suggests a sympathy for social justice causes and an interest in individuals challenging the status quo. He also created illustrations for publications associated with these movements, demonstrating a practical application of his art in support of his beliefs.

Versatility Across Media: Hawkins was not confined solely to oil painting. His artistic output included work in other media, demonstrating his versatility. He is known to have created sculptures, designed decorative objects such as masks, and produced illustrations and works on paper, including watercolours, sometimes in collaboration with other artists like Mademoiselle Clémentine Favarger. This engagement with decorative arts aligns him with the broader Symbolist interest in breaking down hierarchies between fine and applied arts, aiming for a more integrated aesthetic environment, a goal shared by movements like Art Nouveau.

Masterworks and Representative Pieces

Several key works exemplify Louis Welden Hawkins's artistic achievements and stylistic characteristics, securing his place in art history.

The Orphans (Les Orphelins, 1881): This painting marked Hawkins's first major success after its exhibition at the Salon of 1881. Depicting vulnerable figures, it likely showcased his technical skill honed at the Académie Julian while perhaps hinting at the sensitivity and emotional depth that would characterize his later Symbolist work. Its acquisition by the French state for the Musée du Luxembourg was a significant early recognition of his talent, placing him within the national collection alongside established masters.

Séverine (Portrait of Séverine, 1895): Arguably Hawkins's most famous work, this portrait depicts the influential feminist, socialist, and anarchist journalist and writer Séverine. The painting captures her intelligence and intensity, presenting her not just as a society figure but as a woman of conviction. Rendered with Hawkins's characteristic refinement and sensitivity, the portrait transcends mere likeness to become a symbol of the modern, engaged woman. Its context, portraying a figure known for her radical views and humanitarianism (she opposed Boulangism and the death penalty, and defended anarchist figures), adds a layer of social commentary. The work is now housed in the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, highlighting its significance.

The Procession of Souls (Le Foyer / Procession des âmes, 1893): This painting embodies the mystical side of Hawkins's Symbolism. It depicts a line of haloed figures moving slowly along what appears to be a riverbank, suggesting a spiritual journey, perhaps towards the afterlife or an ethereal realm. The atmosphere is one of quiet solemnity and otherworldliness. The use of halos and the processional format evoke religious imagery, but filtered through a Symbolist lens, the meaning remains ambiguous and evocative, prompting contemplation on themes of life, death, and spirituality.

The Sphinx and the Chimera (Le Sphinx et la Chimère, 1906): Created later in his career, this work demonstrates Hawkins's continued fascination with mythology and the fantastical. It portrays two composite creatures from ancient Greek lore – the enigmatic Sphinx and the monstrous Chimera. By juxtaposing these powerful symbols of mystery, danger, and hybridity, Hawkins delves into themes of the subconscious, the unknown, and perhaps the conflicting forces within human nature. The painting showcases his ability to render mythical subjects with a compelling, slightly unsettling presence, characteristic of late Symbolism's exploration of the strange and psychological.

Le Foyer (Home, 1899): This work illustrates Hawkins's ability to infuse an apparently ordinary scene with a sense of mystery and atmosphere. While the title suggests a domestic interior, the painting likely uses light and composition to create an effect that transcends the mundane. Through subtle manipulation of light and shadow, Hawkins could transform familiar settings into spaces charged with emotional or psychological resonance, a common technique within Symbolism to suggest hidden depths beneath surface reality.

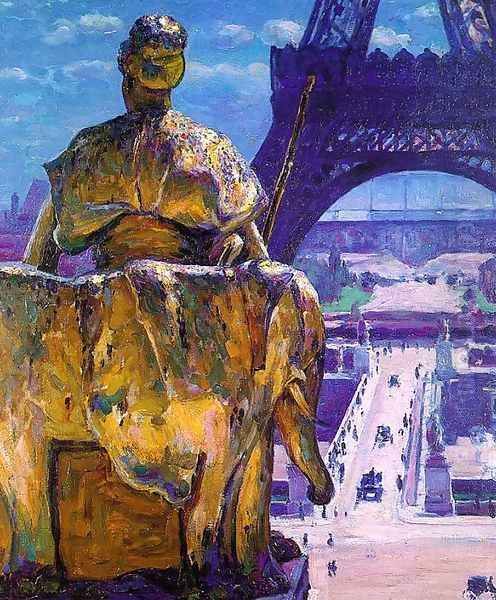

Eiffel Tower from the Trocadéro (c. 1899): This work shows Hawkins engaging with a quintessentially modern Parisian landmark. However, depicted from the Trocadéro, possibly incorporating elements like sculptures representing continents (as were present at the Trocadéro palace), the painting likely filters the iconic structure through his unique sensibility. It would be less about capturing the engineering marvel in an Impressionistic manner and more about integrating it into a composed, perhaps slightly melancholic or atmospheric, urban landscape. It reflects the complex relationship artists of the era had with modernity, often viewing it through a lens of nostalgia or symbolism.

Other notable works mentioned include A Prayer to God, indicating his exploration of religious sentiment, and Fleurs d’ail, praised for its understated style, suggesting a range even within his Symbolist framework. These paintings, alongside his portraits and mythological scenes, contribute to a picture of an artist constantly exploring themes of beauty, spirituality, psychology, and the enigmatic nature of existence.

Connections, Contemporaries, and Influence

Louis Welden Hawkins did not operate in an artistic vacuum. He was part of a rich and dynamic network of artists, writers, and intellectuals in fin-de-siècle Paris, and his relationships and interactions shaped his career and artistic development.

He cultivated important friendships with leading figures in the art world. Notably, he was connected with the American expatriate painter James Abbott McNeill Whistler. Whistler's own aestheticism, his emphasis on tonal harmony, refined compositions, and the idea of "art for art's sake," likely resonated with Hawkins's sensibilities. Both artists shared an interest in elegant portraiture and atmospheric effects, suggesting a mutual influence or shared artistic concerns.

Another significant connection was with the sculptor Auguste Rodin. Rodin, a towering figure in modern sculpture, was also associated with Symbolist circles, particularly through his expressive and psychologically charged works. Friendship with Rodin would have placed Hawkins at the heart of progressive artistic discussions in Paris. Both artists were involved in the breakaway Salon de la Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts, indicating shared dissatisfaction with the established academic Salon.

His association with the journalist Séverine was clearly pivotal, resulting in his most famous portrait and linking him directly to progressive social and political movements. Similarly, his connection with the radical socialist Pierre-Carlet de la Chataigneraie (Capelétan) underscores his engagement with circles beyond the purely artistic mainstream. His collaboration with Mademoiselle Clémentine Favarger on works on paper points to the collaborative spirit present in some artistic quarters.

Within the broader Symbolist movement, Hawkins's work can be situated alongside that of other key figures. While perhaps less overtly mystical than Gustave Moreau or Odilon Redon, he shared their interest in imaginative and non-naturalistic subjects. His refined style and focus on idealized female figures find parallels in the work of Belgian Symbolists like Fernand Khnopff or Jean Delville. He also worked within the same cultural milieu as Symbolist writers like Stéphane Mallarmé and Paul Verlaine, whose poetry sought similar effects of suggestion, musicality, and exploration of inner states, creating a climate where visual artists and writers shared common goals.

Compared to the Post-Impressionists who were his contemporaries, such as Paul Gauguin or Vincent van Gogh, Hawkins's approach was generally more polished and less overtly expressive in its brushwork, aligning more closely with the refined aesthetics of Symbolism and academic tradition, even as he explored modern themes of psychology and social engagement. His teachers, Jules Lefebvre and William Bouguereau, represent the academic tradition against which Symbolism partly reacted, yet their technical instruction undeniably provided Hawkins with the skills he adapted to his own ends. His work offers a bridge between academic finish and Symbolist content.

Later Years and Legacy

In the later part of his career, Louis Welden Hawkins spent considerable time in the region of Brittany. This area, known for its rugged landscapes, distinct culture, and dramatic coastline, attracted many artists during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, including Paul Gauguin and the Pont-Aven school. During his time in Brittany, Hawkins increasingly turned his attention to landscape painting. While likely still imbued with his characteristic sensitivity to light and atmosphere, this focus suggests a shift or expansion in his thematic interests towards the end of his life.

Louis Welden Hawkins passed away in 1910. Recognition, however, sometimes follows artists posthumously. In 1911, the year after his death, he was awarded honours by the Salon, a final acknowledgement of his contributions to French art.

Today, Hawkins's work is represented in major museum collections, testifying to his enduring significance. His early success, The Orphans, remains in the collection of the Musée du Luxembourg in Paris (though works are often transferred, its historical acquisition is key). Other works can be found in the Musée d'Orsay, the primary repository for French art of that period in Paris. The celebrated Portrait of Séverine is a highlight of the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, placing his work alongside another giant of the era.

Louis Welden Hawkins's legacy lies in his unique contribution to the Symbolist movement. As an artist of cosmopolitan background who became a French citizen, he brought a distinct perspective to the Parisian art scene. He excelled in creating works of refined beauty and psychological depth, particularly his portraits of women. His ability to blend Symbolist mystery with elements of academic technique and an awareness of contemporary trends like Impressionism resulted in a subtle and elegant style. Furthermore, his engagement with social issues and radical figures adds another layer to his persona, revealing an artist connected to the intellectual and political ferment of his time. He remains a compelling example of the diversity and complexity of artistic expression during the rich and transformative fin-de-siècle period.

Conclusion

Louis Welden Hawkins offers a portrait of an artist shaped by diverse cultural streams and artistic currents. Born German, raised British, and naturalized French, he embodied a certain European cosmopolitanism. His artistic journey took him from the discipline of academic training under Lefebvre and Bouguereau to the evocative, mysterious realms of Symbolism. Renowned for his exquisitely rendered, dreamlike portraits of women, such as the iconic Séverine, and his explorations of myth and allegory, like The Sphinx and the Chimera, Hawkins carved out a distinctive niche. He navigated the Parisian art world, exhibiting at the Salons, forging connections with major figures like Whistler and Rodin, and engaging with the social ideas of his day. While perhaps not as revolutionary as some of his contemporaries, Hawkins contributed significantly to the Symbolist movement through his elegant style, technical finesse, and sensitive exploration of beauty, mystery, and the inner life. His works continue to resonate, offering glimpses into the sophisticated and often enigmatic spirit of the fin de siècle.