Introduction: An Artist Between Worlds

Hugo Scheiber stands as a fascinating and dynamic figure in the landscape of early 20th-century European art. Born in Budapest in 1873 and passing away in the same city in 1950, Scheiber's life spanned a period of immense artistic upheaval and innovation. He was a quintessential Hungarian modernist, yet his artistic journey and recognition extended far beyond the borders of his homeland, particularly into the vibrant art scenes of Berlin and Rome. Scheiber navigated the swirling currents of Impressionism, Expressionism, Futurism, and Art Deco, forging a unique and instantly recognizable style. His work captured the energy, anxieties, and glamour of modern urban life, often focusing on cafes, jazz clubs, and the bustling city streets. While celebrated internationally during his peak years, particularly through his association with Herwarth Walden's influential Der Sturm gallery in Berlin, he remained somewhat underappreciated in Hungary until after his death. This article delves into the life, evolving style, key works, and historical significance of this important, yet sometimes overlooked, master of modernism.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening in Budapest

Hugo Scheiber's artistic inclinations were perhaps seeded early on. Born in Budapest, the capital of Hungary, which was then part of the vast Austro-Hungarian Empire, he experienced a childhood touched by the world of art, albeit in a practical form. His father worked as a sign painter for the Prater amusement park in Vienna. This exposure to commercial art and stage design might have provided an initial, informal introduction to visual creation. The family later returned to Budapest, and Hugo's formal artistic education was minimal. He briefly attended the School of Applied Arts in Budapest, but like many artists of his generation who chafed against academic constraints, he was largely self-taught.

Financial necessity shaped his early adulthood. Following his father's death, the responsibility of supporting his family fell upon Scheiber. This period likely involved commercial work, forcing him to hone his skills under practical pressures. However, his dedication to fine art persisted. He diligently studied the works of established masters and contemporary trends, gradually developing his technical abilities and artistic vision. The Budapest of the late 19th and early 20th centuries was a city brimming with cultural energy, a melting pot of influences, providing a stimulating, if challenging, environment for a young, aspiring artist.

From Impressionist Influences to Expressionist Force

Scheiber's earliest works, emerging around the turn of the century, show the influence of prevailing late 19th-century styles, particularly Impressionism and Post-Impressionism. Like many artists across Europe, from Claude Monet in France to Károly Ferenczy in Hungary, Scheiber initially explored landscapes and still lifes using brighter palettes and looser brushwork than traditional academic painting allowed. These early pieces often featured scenes from the Hungarian countryside or intimate domestic settings, rendered with a sensitivity to light and atmosphere. They demonstrate a solid foundation in observation and technique, though they don't yet possess the radical energy that would define his mature style.

However, Scheiber was not content to remain within the bounds of Impressionism. The early years of the 20th century saw the explosive arrival of Expressionism, particularly in Germany and Austria. Artists like Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and Erich Heckel of the Die Brücke group in Dresden, and figures associated with Der Blaue Reiter like Wassily Kandinsky and Franz Marc in Munich, were pushing the boundaries of color and form to convey intense inner emotions and critique modern society. Scheiber absorbed these developments, likely through reproductions and exhibitions. By the 1910s, his work underwent a dramatic transformation.

His paintings began to feature bolder, often non-naturalistic colors, distorted perspectives, and jagged, energetic lines. Subjects became more stylized, moving away from direct representation towards emotional and psychological expression. This shift marked his arrival as a truly modern artist, aligning him with the broader Central European Expressionist movement. His unique take on Expressionism often retained a certain decorative quality, hinting at the stylistic fusion that would characterize his later work. This burgeoning Expressionist phase laid the groundwork for his international connections and future stylistic explorations.

The Berlin Connection: Der Sturm and Herwarth Walden

A pivotal moment in Scheiber's career came with his connection to Herwarth Walden (Georg Levin), the influential German writer, musician, and gallery owner who was a central figure in the European avant-garde. Walden founded the magazine Der Sturm (The Storm) in 1910 and opened the Der Sturm gallery in Berlin in 1912. This gallery became a crucial platform for Expressionist, Futurist, Cubist, and abstract artists from across Europe, exhibiting works by Oskar Kokoschka, Marc Chagall, members of Die Brücke and Der Blaue Reiter, and many others.

Scheiber began exhibiting with Der Sturm around 1919-1920. This association was immensely important. It placed his work at the heart of the international avant-garde, exposing it to a sophisticated audience and influential critics. Berlin, especially in the chaotic but culturally fertile years of the Weimar Republic, was a magnet for artists, writers, and intellectuals. Being part of the Sturm circle provided Scheiber with validation, visibility, and connections that were harder to achieve within the more conservative Hungarian art scene.

Walden recognized the power and originality of Scheiber's vision. Scheiber's Expressionist works, with their vibrant colors and dynamic compositions, fit well within the gallery's progressive program. This Berlin period was crucial for Scheiber's development, pushing him further towards stylistic experimentation and solidifying his reputation outside Hungary. His time in Berlin also facilitated collaborations and friendships, most notably with fellow Hungarian artist Béla Kádár.

Collaboration and Shared Visions: Scheiber and Béla Kádár

During his time associated with Der Sturm in Berlin, Hugo Scheiber formed a close working relationship with another expatriate Hungarian artist, Béla Kádár (1877-1956). Kádár, whose style also blended Expressionism with folk art influences and later Art Deco elements, shared a similar trajectory of seeking recognition outside Hungary. The two artists often exhibited together, particularly under the auspices of Herwarth Walden's gallery. Their joint shows in Berlin and other European cities helped to establish a distinct presence for Hungarian modernism on the international stage.

While their styles had affinities – both employed bold colors, simplified forms, and often depicted scenes of modern life or stylized figures – there were also subtle differences. Kádár's work sometimes drew more explicitly on Hungarian folk motifs, creating a lyrical, almost fairytale-like quality. Scheiber's art, particularly as it evolved, often possessed a sharper, more angular dynamism, reflecting perhaps a stronger engagement with Futurism and the relentless pace of the metropolis.

Their collaboration was mutually beneficial. It provided companionship and artistic dialogue in a foreign city and amplified their impact through joint exhibitions. Presenting their work together highlighted the vitality and unique character of contemporary Hungarian art to an international audience. This partnership remains a significant chapter in the story of Hungarian artists navigating the complex European art world of the 1920s.

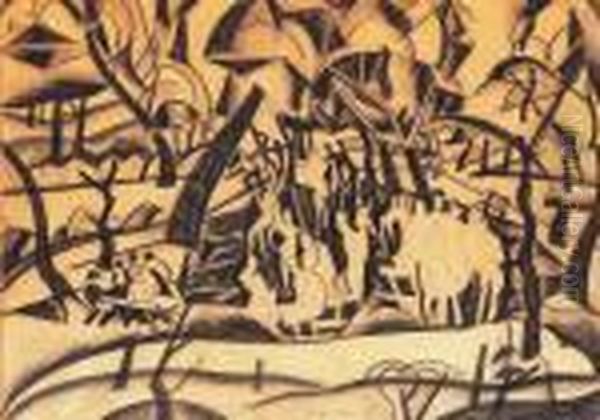

Embracing Futurism: Dynamism and the Modern Age

While Expressionism formed a core part of Scheiber's artistic identity, he was also receptive to other avant-garde movements sweeping across Europe. Italian Futurism, launched by Filippo Tommaso Marinetti's manifesto in 1909, particularly resonated with Scheiber's interest in capturing the energy and speed of modern life. Futurism celebrated dynamism, technology, the machine, and the city, themes that increasingly appeared in Scheiber's work. Artists like Umberto Boccioni, Giacomo Balla, and Carlo Carrà sought to represent movement and the simultaneity of experience through fragmented forms and "lines of force."

Scheiber met Marinetti, the charismatic leader of the Futurist movement, likely during the early 1920s. This connection proved fruitful. Marinetti recognized a kindred spirit in Scheiber's dynamic depictions of urban scenes. Consequently, Scheiber was invited to participate in major Futurist exhibitions, most notably the great Futurist exhibition held in Rome in 1933. This inclusion was a significant international acknowledgment of his alignment with the movement's core principles, even if his style remained distinct from the mainline Italian Futurists.

Scheiber integrated Futurist ideas into his existing Expressionist framework. He adopted dynamic diagonal lines, fragmented perspectives, and repetitive forms to convey movement and the sensory overload of the modern city. His paintings of speeding trains, bustling cafes, and energetic dancers pulsate with a Futurist-inspired vitality. This fusion of Expressionist emotional intensity with Futurist dynamism became a hallmark of his mature style, setting him apart from many of his contemporaries.

Art Deco Flair and the Roaring Twenties Aesthetic

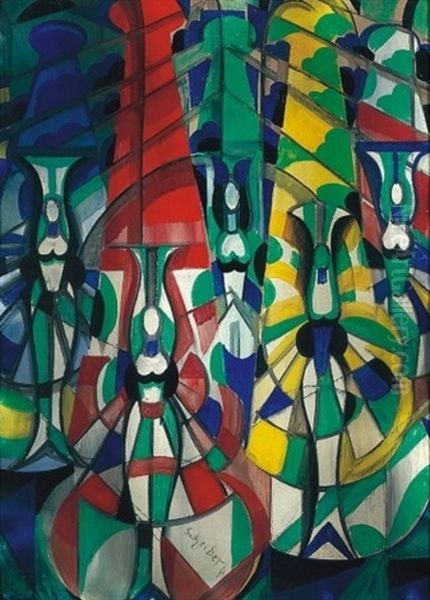

As the 1920s progressed, Scheiber's style continued to evolve, absorbing elements of the burgeoning Art Deco movement. Art Deco, with its emphasis on streamlined forms, geometric patterns, rich materials, and sophisticated glamour, provided a new visual language that suited Scheiber's fascination with modern urban life, particularly its nightlife and entertainment scenes. His work from this period often depicts the quintessential figures and settings of the Roaring Twenties: flappers with bobbed hair, jazz musicians, smoky cabarets, elegant couples in cafes, and the general buzz of metropolitan existence.

His forms became more stylized, sometimes simplified into elegant, geometric shapes. While retaining the vibrant color palette of his Expressionist phase, the application often became smoother, the lines cleaner, reflecting Art Deco's decorative sensibility. He masterfully captured the era's blend of excitement, anxiety, and artificiality. His figures, though stylized, often convey a sense of psychological depth, hinting at the inner lives behind the fashionable facades.

This Art Deco influence is particularly evident in his depictions of women, who are often portrayed with an air of modern independence and chic sophistication, reminiscent perhaps of the portraits by Tamara de Lempicka, though Scheiber's approach remained more rooted in Expressionist energy than Lempicka's cool classicism. This fusion of Expressionism, Futurism, and Art Deco created a highly personal and captivating style that perfectly encapsulated the spirit of the interwar period in cities like Berlin and Budapest.

Recurring Themes: The Pulse of the Metropolis

Throughout his mature period, Hugo Scheiber consistently returned to a set of core themes, primarily centered on the experience of modern urban life. He was fascinated by the city's relentless energy, its places of social gathering, and the diverse characters who inhabited it. Cafes and bars feature prominently, depicted as hubs of conversation, observation, and sometimes alienation. He captured the rhythm and movement of jazz clubs and cabarets, with dynamic portrayals of musicians lost in their performance and dancers caught in swirling motion.

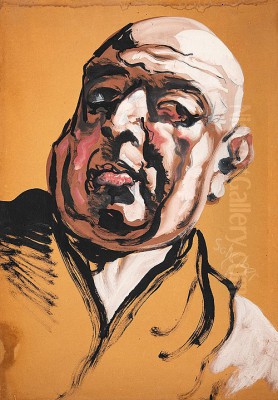

Transportation – trains, cars, bustling streets – also appears frequently, symbolizing the speed and technological advancement of the modern age, often rendered with Futurist-inspired lines of force. Portraits form another significant part of his oeuvre. These are rarely conventional likenesses; instead, they are stylized interpretations that use form and color to convey personality or mood, often with an angular, slightly distorted quality that reflects his Expressionist roots.

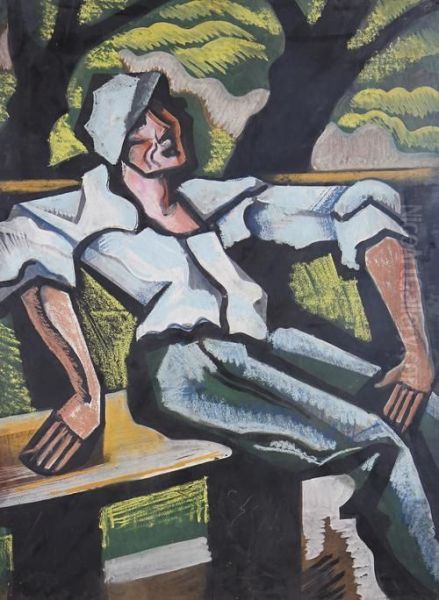

Even when depicting seemingly simpler scenes, like figures walking in a park or sitting on a bench, Scheiber imbued them with a sense of modern sensibility. His unique stylistic blend allowed him to portray the excitement and glamour of the city, but also hints of the underlying tension and anonymity of metropolitan existence. His work serves as a vibrant visual chronicle of the social and cultural landscape of Central Europe during a period of profound transformation.

Analysis of Representative Works

Several key works exemplify Hugo Scheiber's stylistic evolution and thematic concerns:

Railway Crossing (c. 1921): This painting showcases Scheiber's engagement with Futurist themes of speed and technology, combined with Art Deco stylization. The dynamic composition, likely featuring converging lines and simplified forms of trains or signals, captures the energy and potential danger of the modern industrial landscape. The use of bold color and geometric shapes is characteristic of his work from the early 1920s.

Man on a Bench (1920s): Works depicting solitary figures in urban settings are common in Scheiber's oeuvre. This painting likely employs his characteristic blend of Expressionist distortion and Futurist/Art Deco stylization to portray a modern city dweller. The figure might appear contemplative or alienated amidst the urban environment, rendered with angular forms and expressive color choices that convey mood rather than strict realism.

In Park: This title suggests a slightly different facet of urban life – moments of leisure and relative tranquility. However, rendered in Scheiber's style, even a park scene would likely possess a dynamic quality. Expect stylized trees and figures, perhaps simplified into geometric forms, with vibrant, possibly non-naturalistic colors capturing the atmosphere of the park within the bustling city. It reflects his ability to apply his modern vision to various aspects of contemporary experience.

Tree Man: This intriguing title points towards a more symbolic or surreal work, possibly blending human and natural forms. It likely exemplifies Scheiber's Expressionist leanings, using the anthropomorphized tree to explore themes of nature versus modernity, or perhaps deeper psychological states. The fusion of styles would be key here, potentially combining organic, distorted forms with the energetic lines of Futurism.

Tancolo (Dancer): Depictions of dancers and cabaret performers were frequent subjects for Scheiber. This work would likely capture the movement and energy of performance, using swirling lines, vibrant colors, and fragmented forms influenced by both Expressionism and Futurism. It would aim to convey the rhythm and atmosphere of the performance space, a quintessential theme of the Roaring Twenties.

These examples highlight the consistent stylistic threads in Scheiber's work – the fusion of Expressionist color and emotion, Futurist dynamism, and Art Deco stylization – applied to his keen observations of modern life.

International Recognition vs. Hungarian Reception

Hugo Scheiber's career presents a striking contrast between his reception abroad and in his native Hungary. Internationally, particularly during the 1920s and early 1930s, he achieved considerable recognition. His association with Der Sturm placed him at the forefront of the European avant-garde. He exhibited widely across the continent, including significant shows in Berlin, Vienna, Rome (including the Futurist exhibition), London, and Paris.

A notable milestone was his inclusion in the "International Exhibition of Modern Art" organized by the Société Anonyme in New York in 1926. This pioneering organization, founded by Katherine S. Dreier, Marcel Duchamp, and Man Ray, aimed to introduce American audiences to European modernism. Scheiber's participation underscores his standing within the international network of avant-garde artists during this period. His connections with figures like Marinetti further cemented his reputation abroad.

In Hungary, however, recognition was slower and more limited during his lifetime. While he was a member of Hungarian art groups, such as KÚT (New Society of Artists), the prevailing artistic tastes in Hungary were often more conservative. His radical style, blending Expressionism and Futurism, did not always find favor with the established art institutions or the broader public. Compared to artists like József Rippl-Rónai, whose work evolved from Post-Impressionism, or even the activist avant-gardism of Lajos Kassák, Scheiber occupied a unique, sometimes isolated, position. It was largely after his death that his importance within the narrative of Hungarian modernism began to be fully appreciated within his homeland.

War, Politics, and Artistic Resilience

Scheiber's life and career were inevitably impacted by the turbulent political events of the first half of the 20th century. He served in the Austro-Hungarian army during World War I, an experience that undoubtedly affected him, as it did countless artists and intellectuals of his generation. The post-war period saw him gravitate towards Berlin, partly seeking greater artistic freedom and opportunity than was available in the politically unstable Hungary of the time.

His Jewish heritage became a significant factor with the rise of fascism across Europe in the 1930s. Although he had gained recognition in Italy through his Futurist connections, the increasingly hostile political climate posed a threat. In Hungary, under the authoritarian Horthy regime and later during the Nazi occupation and the subsequent Communist takeover, artists faced censorship and persecution. Scheiber's modern style, like that of many avant-garde artists, was likely viewed with suspicion by authoritarian regimes. His work may have been unofficially or officially marginalized, potentially labeled as "degenerate," mirroring the fate of many modernists in Nazi Germany, such as Emil Nolde or Otto Dix.

Despite these immense challenges – political instability, war, anti-Semitism, and shifting regimes that were often hostile to avant-garde art – Scheiber continued to create. He remained in Budapest through World War II and its aftermath, working persistently even when exhibition opportunities dwindled and official recognition was non-existent. This period, from the mid-1930s until his death in 1950, was marked by hardship and relative obscurity. His perseverance in the face of adversity speaks volumes about his dedication to his artistic vision.

Legacy and Historical Position

Hugo Scheiber's death in 1950 occurred before his full significance was widely acknowledged, particularly in Hungary. However, in the subsequent decades, his work has been re-evaluated, and his position as a key figure in Hungarian and Central European modernism has been firmly established. He is recognized for his unique synthesis of major early 20th-century art movements – skillfully blending the emotional intensity of Expressionism, the dynamic energy of Futurism, and the stylized elegance of Art Deco.

His importance lies not only in his stylistic innovation but also in his role as a chronicler of his time. His paintings offer a vibrant, insightful glimpse into the urban culture of Budapest and Berlin during the interwar years, capturing both the exhilaration and the underlying anxieties of the modern era. He stands alongside other significant Hungarian modernists who navigated the international art scene, such as Béla Kádár, Vilmos Huszár (associated with De Stijl), and members of the earlier influential group The Eight (Nyolcak), like Robert Berény and Ödön Márffy.

Today, Scheiber's works are held in important public collections, including the Hungarian National Gallery in Budapest, the Janus Pannonius Museum in Pécs, and the Kiscelli Museum in Budapest, as well as numerous private collections internationally. His paintings command significant prices at auction, reflecting a growing appreciation for his artistic contribution. He remains a testament to the power of individual artistic vision to absorb diverse influences and create something new and compelling, even amidst challenging historical circumstances.

Conclusion: A Vibrant Voice in Modernism

Hugo Scheiber's artistic journey was one of constant evolution and adaptation. From his early Impressionist-influenced works to his powerful Expressionist canvases, his dynamic Futurist-inspired cityscapes, and his chic Art Deco scenes, he remained attuned to the artistic currents of his time while forging a distinctly personal style. His ability to synthesize these diverse influences into a cohesive and energetic visual language makes him a standout figure. He captured the pulse of modern life – its speed, its glamour, its social interactions, and its underlying tensions – with a vibrancy and immediacy that still resonates today. Though overshadowed at times by political turmoil and shifting artistic tastes, especially within his homeland during his later years, Hugo Scheiber's legacy endures as a vital and exciting contributor to the rich tapestry of 20th-century European modernism. His work continues to engage viewers with its bold colors, dynamic compositions, and insightful portrayal of an era of profound change.