Agnes Cleve stands as a significant, yet sometimes overlooked, figure in the landscape of early 20th-century European art. A key pioneer of Modernism in Sweden, her life and work encapsulate the dynamic shifts occurring in art and society during her time. Born in Uppsala, Sweden, on August 23, 1876, and passing away in Stockholm on March 11, 1951, Cleve forged a path characterized by bold experimentation with color and form, drawing inspiration from international avant-garde movements while focusing her lens on the burgeoning industrial and urban life of her homeland. Her journey through the art world reflects both the opportunities and challenges faced by female artists seeking recognition in a transformative era.

Formative Years and Artistic Education

Agnes Cleve's upbringing provided a fertile ground for intellectual and artistic development. She was born into a prominent academic family in Uppsala; her father, Per Teoder Cleve, was a distinguished professor of chemistry and geology at Uppsala University, known for discovering the elements holmium and thulium. Her mother, Alma Öhbom (sometimes recorded as Öma Albö in initial sources, but generally known as Alma Öhbom), was a writer and translator, contributing to the cultured environment of their home. This background likely instilled in Agnes a sense of intellectual curiosity and a drive for achievement.

Her formal artistic training began seriously at the turn of the century. Cleve attended the progressive Valand Academy of Fine Arts (Valands konstskola) in Gothenburg. This institution was notable for its relatively forward-thinking approach under certain instructors. Crucially, she studied under Carl Wilhelmson, a respected painter and influential teacher known for his advocacy of equal educational opportunities for male and female students. This was particularly important in an era when women's access to higher art education was often restricted or qualitatively different from that offered to men.

At Valand, Cleve was part of a talented cohort of emerging artists who would also make their mark on Swedish art. Among her contemporaries were figures like Mollie Faustman, who would become known as a painter, illustrator, and critic; Vera Nilsson, another significant modernist painter; and Ellen Trotzig, who developed a distinctive style often focused on landscapes. Studying alongside these peers provided a stimulating environment for artistic growth and the exchange of ideas, fostering a sense of shared purpose among these aspiring modernists. Cleve's early work from this period sometimes incorporated techniques like Pointillism, alongside more traditional portraiture, hinting at her burgeoning interest in contemporary stylistic developments.

Parisian Immersion and the Embrace of Modernism

Like many ambitious artists of her generation, Agnes Cleve recognized the necessity of experiencing the vibrant art scene of Paris, the undisputed capital of the avant-garde in the early 20th century. She traveled to Paris before World War I, immersing herself in the city's dynamic artistic milieu. This period proved transformative for her stylistic development. She enrolled at the Académie de La Palette, a progressive art school known for attracting international students interested in Cubism and other modern movements.

At La Palette, Cleve studied under influential figures associated with Cubism, such as Henri Le Fauconnier and Jean Metzinger. These artists were key theorists and practitioners of the Cubist movement, exploring new ways of representing form and space by fragmenting objects and depicting them from multiple viewpoints simultaneously. Exposure to their teaching and the broader Cubist aesthetic profoundly impacted Cleve's approach to composition and representation. She began to incorporate faceted forms and dynamic spatial arrangements into her own work.

Beyond the formal instruction at the academy, Cleve actively engaged with the wider Parisian art world. She encountered the work of Fauvist painters, known for their radical use of non-naturalistic, intense color to convey emotion and structure their compositions. The influence of artists like Henri Matisse and André Derain can be discerned in Cleve's increasingly bold and expressive palette. Furthermore, she established connections with other key figures of the international avant-garde, including the German Expressionist painter Gabriele Münter and the Russian pioneer of abstract art, Wassily Kandinsky, both associated with the Blue Rider group. She also absorbed the ideas of Orphism, a colorful offshoot of Cubism championed by Robert Delaunay and Sonia Delaunay, whose rhythmic compositions and focus on light and color resonated with her developing sensibilities.

This immersion in Paris equipped Cleve with a sophisticated understanding of the latest artistic currents. She synthesized these influences – the structural innovations of Cubism, the chromatic freedom of Fauvism, and the spiritual and abstract explorations of Kandinsky – into a personal style characterized by vibrant color, rhythmic energy, and a distinctly modern sensibility. She returned to Sweden armed with a new artistic language, ready to apply it to her own environment.

Capturing the Modern Metropolis: Themes and Subjects

Upon returning to Sweden, and particularly during her time living and working in Stockholm, Agnes Cleve directed her newly honed modernist vision towards capturing the essence of contemporary urban life. She became one of the foremost artistic chroniclers of the rapidly changing Swedish landscape, focusing specifically on the dynamism, industry, and sometimes chaotic energy of the modern city. This choice of subject matter set her apart from more traditional artists and aligned her firmly with the avant-garde's interest in reflecting the realities of 20th-century existence.

Her canvases often pulsed with the rhythm of Stockholm. She depicted the city's expanding infrastructure, painting bridges, quays, and construction sites. Factories, with their smoking chimneys and imposing structures, became recurring motifs, symbolizing the industrialization transforming Swedish society. Cleve wasn't merely documenting these scenes; she sought to convey the feeling of the modern city – its movement, its power, its blend of human activity and mechanical force. She employed strong colors and dynamic, often fragmented compositions to express this vitality.

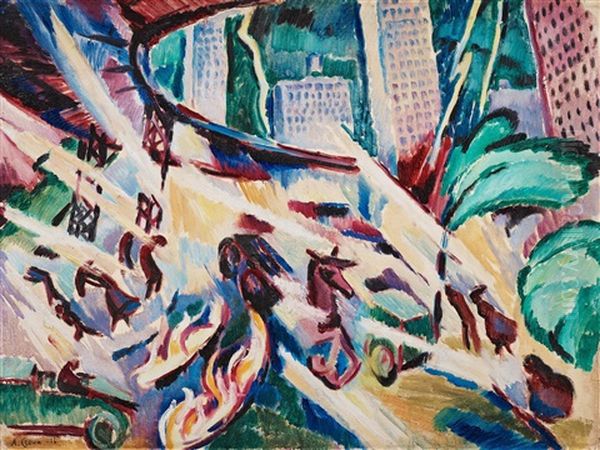

A key example of this focus is her painting Sankt Eriksbron (St. Erik's Bridge). This work vividly portrays the bridge, a significant piece of Stockholm infrastructure, not as a static monument but as a nexus of urban energy. The composition is alive with movement, featuring bold color contrasts, simplified forms, and the prominent depiction of factory smoke billowing into the sky, rendered with expressive, rhythmic brushstrokes. The painting encapsulates her ability to fuse observed reality with a powerful, subjective, and distinctly modern interpretation.

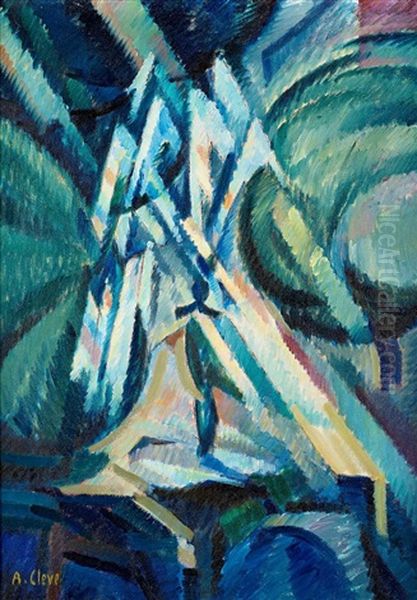

Other notable works further illustrate her engagement with modern themes. New York Fire (1916), likely inspired by accounts or images of the American metropolis, demonstrates her interest in dramatic, large-scale urban events and her ability to translate them into dynamic visual language. Vision II (1925) suggests a more abstract or symbolic engagement with modern experience, moving beyond direct representation towards conveying inner states or broader concepts related to the era. Works like Stockholms ström (Stockholm Stream) and Hamnarbeterskor (Harbour Workers) also highlight her commitment to depicting the city's waterways and the labor that powered its growth. Through these subjects, Cleve asserted the relevance of contemporary life as a valid and vital source for artistic expression.

Artistic Partnerships and Personal Life

Agnes Cleve's personal life was intertwined with her artistic journey, particularly through her second marriage. In 1901, she first married Ernst Lindesjöö, a lawyer. This marriage, however, did not last. Her most significant personal and professional relationship began later. In 1915, she married John Jon-And (sometimes spelled John Jon-Ando), an artist who was thirteen years her junior. Jon-And was also exploring modernist idioms, and their union marked the beginning of a period of close artistic collaboration and shared exploration.

Together, Cleve and Jon-And formed an artistic partnership, navigating the currents of Swedish and international modernism. They shared studio spaces, exhibited together, and likely influenced each other's work during the years of their marriage. They were both deeply interested in translating the principles of Cubism, Expressionism, and potentially Futurism (given their focus on dynamism and the machine age) into a Swedish context. Their shared life provided a supportive, albeit potentially competitive, environment for artistic experimentation. They had one son together, solidifying their family unit for a time.

Despite their shared artistic passions and endeavors, the marriage between Agnes Cleve and John Jon-And eventually ended in divorce. The reasons for the dissolution are personal, but it's noteworthy that even after separating, their paths likely continued to cross within the relatively small Swedish art world. The collaboration during their marriage years, however, remains a significant aspect of both their careers, representing a period of intense creative exchange and mutual engagement with the avant-garde.

Cleve's background, coming from an established intellectual family, combined with her marriages – first to a professional and then to a fellow artist – paints a picture of a woman navigating the social and professional expectations of her time while pursuing an independent artistic career. Her ability to form a significant artistic partnership, even one that ultimately did not last personally, highlights her deep commitment to her creative practice and her engagement with the community of modern artists.

Exhibitions, Reception, and Recognition

Throughout her career, Agnes Cleve actively sought to exhibit her work and engage with the contemporary art scene, both in Sweden and internationally. She participated in numerous exhibitions, showcasing her evolving modernist style. One important venue for her was the Gummeson Gallery (Gummesons Konstgalleri) in Stockholm, a significant hub for modern art in Sweden during the early 20th century. Exhibiting at Gummeson placed her work alongside that of other leading Swedish and international modernists, signaling her position within the avant-garde.

Her work garnered attention and critical responses that reflected the often-polarized opinions surrounding modern art at the time. Some critics praised her bold use of color, her dynamic compositions, and her ability to capture the spirit of the modern age. For instance, she received positive reviews for her participation in exhibitions organized by the Association of Swedish Women Artists (Föreningen Svenska Konstnärinnor), indicating recognition within the community of female artists. A notable exhibition in Stockholm in 1921 also brought her favorable notice.

However, like many modernists pushing boundaries, Cleve also faced criticism. Some commentators found her work challenging, perhaps perceiving her fragmented forms or non-naturalistic colors as lacking clarity or traditional finish. This kind of mixed reception was common for artists breaking from academic conventions. The very aspects of her work that defined its modernity – the vibrant palette, the rhythmic energy, the sometimes abstracting tendencies – could be unsettling to viewers accustomed to more conservative styles.

Despite exhibiting internationally and gaining a degree of recognition within progressive art circles, a significant indicator of establishment acceptance often eluded her during her lifetime: major acquisition by leading public museums. While her work was seen and discussed, it was not collected by institutions like Sweden's Nationalmuseum until much later. This reflects a broader pattern where radical art, particularly by female artists, often took longer to be fully accepted and canonized by the official art establishment. Her reputation, therefore, was primarily built within the circles of fellow artists, supportive critics, and galleries dedicated to modernism, rather than through widespread institutional endorsement during her active years.

Context within Swedish and International Modernism

Agnes Cleve's artistic journey places her firmly within the first wave of Swedish modernists who sought to break from the prevailing National Romanticism and academic traditions of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. She belonged to a generation that looked outward, particularly towards Paris, for inspiration, eager to participate in the international dialogue of the avant-garde. Her work stands as a testament to the successful integration of these international influences into a distinctly Swedish context.

In Sweden, she was a contemporary of other key modernists, though her style maintained its unique characteristics. Figures like Isaac Grünewald and Sigrid Hjertén (who often worked closely together) were also central to introducing vibrant color and Post-Impressionist and Fauvist principles into Swedish art, often focusing on intimate scenes or expressive landscapes. Gösta Adrian-Nilsson (GAN) explored a more stylized form of Cubism and Futurism, often with homoerotic undertones and a focus on sailors, athletes, and modern technology. Artists like Einar Jolin and Nils Dardel developed their own sophisticated, sometimes decorative or naive-inflected, modernist styles. Cleve's particular contribution lies in her consistent focus on the urban and industrial landscape, rendered with a dynamic fusion of Cubist structure and Expressionist color, setting her apart from the more lyrically inclined or purely abstract tendencies of some peers.

Her education under Carl Wilhelmson connects her to a lineage valuing solid craftsmanship alongside modern expression, while her studies alongside Mollie Faustman, Vera Nilsson, and Ellen Trotzig place her within a crucial group of pioneering female modernists in Sweden. Her collaboration with John Jon-And further cemented her engagement with the core group experimenting with avant-garde ideas.

Internationally, her work resonates with the broader currents of European modernism. Her engagement with Cubism connects her to the foundational work of Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, and more directly to the teachings of Metzinger and Le Fauconnier at La Palette. Her vibrant palette echoes the Fauvist explorations of Matisse and Derain. Her contact with Wassily Kandinsky and Gabriele Münter links her to German Expressionism and the move towards abstraction, while her affinity for rhythmic color and form aligns with the Orphism of Robert and Sonia Delaunay. Cleve was not merely passively receiving these influences; she was actively selecting, synthesizing, and transforming them to articulate her own vision of modern life as experienced in Sweden. She stands as an important bridge, demonstrating how international avant-garde ideas were received, adapted, and given unique expression by artists working outside the major art centers like Paris or Berlin.

Legacy and Reassessment

While Agnes Cleve may not have achieved the same level of widespread fame as some of her male contemporaries during her lifetime, her importance as a pioneer of Swedish modernism has become increasingly recognized in the decades following her death in 1951. Her work represents a vital contribution to the development of avant-garde art in Sweden, particularly through her distinctive focus on urban and industrial themes and her bold synthesis of international styles.

Posthumous exhibitions have played a crucial role in reassessing her legacy. A significant memorial exhibition held in 1964 helped to bring renewed attention to her oeuvre and solidify her place in Swedish art history. More recently, efforts by curators and art historians to shed light on the contributions of early 20th-century women artists have further elevated her status. This includes scholarly research, publications, and the inclusion of her work in major survey exhibitions of Swedish modernism.

A tangible sign of this reassessment is the acquisition of her works by major institutions that had overlooked her during her lifetime. Notably, Sweden's Nationalmuseum in Stockholm has acquired works by Cleve, acknowledging her significance and ensuring her art is accessible to contemporary audiences. Publications like exhibition catalogues, such as "Utopia and Reality: Modernity in Sweden 1900-1960," and scholarly articles discussing Swedish Cubism or acquisitions by museums now regularly include her as a key figure.

Agnes Cleve's legacy lies in her role as an early adopter and skilled interpreter of international modernist idioms, applying them with originality to Swedish subjects. She was among the first Swedish artists to consistently engage with the visual language of Cubism and Fauvism and to focus intently on the dynamism of the modern city. As a female artist navigating the challenges of the early 20th-century art world, her perseverance and artistic achievements are particularly noteworthy. She remains an important figure for understanding the complexities of Swedish modernism and the vital role women played in shaping its trajectory.

Conclusion: An Enduring Modern Vision

Agnes Cleve's artistic career charts a course through the heart of early European modernism. From her foundational studies under progressive teachers like Carl Wilhelmson to her transformative experiences in Paris absorbing the lessons of Cubism and Fauvism from artists like Le Fauconnier, Metzinger, Kandinsky, and the Delaunays, she forged a unique and powerful artistic voice. Her marriage and collaboration with John Jon-And further situated her within the active currents of avant-garde exploration.

Her most enduring contribution lies in her compelling depictions of the modern Swedish city, particularly Stockholm. Through works like Sankt Eriksbron, she captured the energy, industry, and transformation of her time with a vibrant palette and dynamic compositions that synthesized international trends with local realities. While contemporary recognition by major institutions was slow to come, her position as a key pioneer, alongside contemporaries like Grünewald, Hjertén, and GAN, is now firmly established.

Agnes Cleve's work stands as a testament to the power of modernist expression to capture the complexities of 20th-century life. Her bold use of color, her rhythmic compositions, and her focus on the urban landscape offer a distinct and valuable perspective within the broader narrative of Swedish and European art history. As a pioneering woman artist who navigated the international avant-garde and brought its innovations home, her legacy continues to resonate, reminding us of the rich diversity of voices that shaped the modern artistic vision.