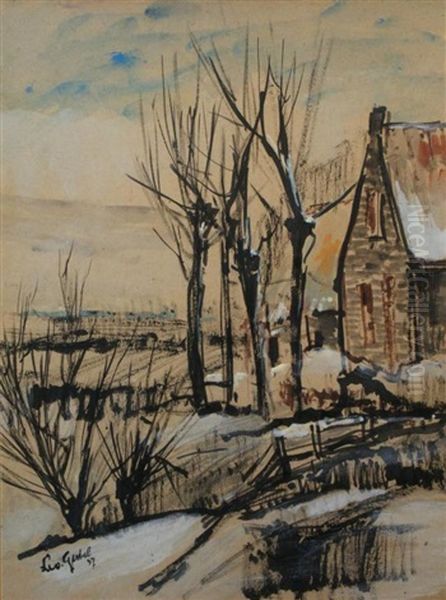

Leo Gestel stands as a significant figure in the landscape of early 20th-century Dutch art. Born Leendert Gestel on November 11, 1881, in Woerden, South Holland, and passing away on November 26, 1941, in Hilversum, North Holland, his life spanned a period of intense artistic innovation and upheaval across Europe. Gestel was not merely a participant but a driving force within Dutch Modernism, experimenting restlessly across various avant-garde styles and contributing significantly to the nation's artistic identity shift away from the dominant Hague School Impressionism of the late 19th century. He is often mentioned in the same breath as his contemporaries Piet Mondrian and Jan Sluijters, forming a core trio that propelled Dutch painting into the modern era, particularly through their exploration of light and colour in what became known as Dutch Luminism.

Gestel's artistic journey was marked by a remarkable versatility and an unwillingness to be confined to a single stylistic dogma. He absorbed and synthesized influences from Impressionism, Pointillism, Fauvism, Cubism, Futurism, and Expressionism, forging a unique path characterized by vibrant colour palettes, dynamic compositions, and a profound sensitivity to the effects of light. His legacy extends beyond easel painting to encompass significant work in graphic arts, illustration, and even mural design, showcasing a multifaceted talent dedicated to exploring the expressive potential of modern art forms. Understanding Leo Gestel is crucial to appreciating the complex and dynamic evolution of modern art in the Netherlands.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Leo Gestel's entry into the art world was perhaps preordained. He was born into an artistic family; his father, Willem Gestel, was himself a painter and the director of an evening school for applied arts. It was Willem who provided Leo with his initial drawing lessons, laying the foundation for his future career. This familial connection to art extended to his uncle, Dimmen Gestel, a painter and printer based in Eindhoven. Dimmen was notably acquainted with Vincent van Gogh, having reportedly painted outdoors alongside the Post-Impressionist master during Van Gogh's time in Nuenen. This connection, however indirect, placed the young Gestel within a lineage touched by one of the most revolutionary figures in modern art history.

Despite his father's initial desire for him to become a drawing teacher, Leo harboured ambitions of being an independent artist. He pursued formal training, attending the Rijksnormaalschool voor Teekenonderwijzers (National Normal School for Drawing Teachers) in Amsterdam and later taking evening classes at the prestigious Rijksakademie van Beeldende Kunsten (State Academy of Fine Arts). During these formative years, Gestel's work reflected the prevailing influences of the time, particularly the atmospheric realism of the Hague School, exemplified by artists like Anton Mauve, Jozef Israëls, and the Maris brothers (Jacob, Matthijs, and Willem), as well as the more urban, dynamic Impressionism of Amsterdam, championed by George Hendrik Breitner.

However, Gestel quickly sought to move beyond these established styles. His early exposure to modern art likely came through exhibitions in Amsterdam and his developing friendships with other forward-thinking artists. He began experimenting with brighter colours and looser brushwork, signalling an early departure from academic constraints and a growing interest in the subjective potential of colour and form. This period laid the groundwork for his subsequent embrace of more radical European movements.

The Embrace of Luminism

Around 1907-1910, Gestel, alongside Piet Mondrian and Jan Sluijters, became a leading exponent of Dutch Luminism (or Luminisme). This movement, while sharing a name with an earlier American style, was distinctly Dutch and represented a local adaptation of French Post-Impressionist techniques, particularly Pointillism and Fauvism. It was less a formal group and more a shared tendency among artists seeking to capture the intense effects of light through pure, often unmixed colours applied in distinct strokes, dots, or patches. The goal was not merely optical representation but conveying the emotional and spiritual intensity of light and colour.

Gestel's Luminist works are characterized by their dazzling vibrancy and energetic brushwork. He employed techniques learned from Neo-Impressionists like Georges Seurat and Paul Signac, using dots and small dashes of complementary colours placed side-by-side to create a shimmering effect when viewed from a distance. However, unlike the more systematic approach of Seurat, Gestel's application was often more intuitive and expressive, aligning him also with the bold colour choices of Fauvist painters like Henri Matisse and André Derain. Dutch Luminism often retained a connection to recognizable subject matter – landscapes, portraits, still lifes – but imbued them with an almost mystical radiance.

A quintessential example of Gestel's Luminist phase is Herfst (Autumn), often dated around 1909 (though sometimes cited as 1911). Housed in the Kunstmuseum Den Haag, this painting depicts a landscape, likely near Woerden or in the Gooi region where he often worked, bathed in the golden light of autumn. Gestel uses short, energetic strokes of yellow, orange, blue, and violet to capture the flickering sunlight on foliage and water. The forms are simplified, and the emphasis is clearly on the atmospheric effect and the sheer brilliance of the colour interactions. Other key figures associated with Dutch Luminism include Jan Toorop and Johan Thorn Prikker, who also explored Symbolist themes through similar techniques.

Parisian Encounters and Avant-Garde Exploration

Like many ambitious artists of his generation, Gestel recognized the importance of Paris as the epicentre of the European avant-garde. He made several trips to the French capital, starting around 1904, immersing himself in its vibrant art scene. These visits proved transformative, exposing him directly to the latest artistic revolutions and accelerating his stylistic development. He studied the works of the Impressionists and Post-Impressionists firsthand, solidifying his understanding of colour theory as practiced by Seurat and Signac.

Crucially, his time in Paris brought him into contact with Fauvism and the nascent Cubist movement. The Fauves' radical use of non-naturalistic colour for emotional impact resonated with Gestel's own inclinations. The work of Matisse, Derain, and fellow Dutchman Kees van Dongen, who had become a prominent figure in Parisian Fauvism, undoubtedly left its mark. Simultaneously, the analytical deconstruction of form pioneered by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque in Cubism offered a new way of representing reality, breaking objects and figures into geometric facets and showing multiple viewpoints simultaneously.

Gestel began to incorporate elements of these styles into his own work. His palette remained bright, but his forms became increasingly fragmented and angular. He experimented with flattening space and emphasizing structure, moving away from the purely atmospheric concerns of Luminism towards a more analytical approach. This synthesis is evident in works created around 1910-1913. He also became aware of Italian Futurism, with its emphasis on dynamism, speed, and the machine age, championed by artists like Umberto Boccioni and Gino Severini. The energy and fragmented forms of Futurism found echoes in Gestel's evolving style.

A key moment was his participation in the Internationale Tentoonstelling van Werken van Levende Meesters (International Exhibition of Works by Living Masters) at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam in 1912, which included significant Cubist and Futurist works. In 1913, Gestel himself exhibited works reflecting these influences, notably at the Kunstzaal Roos in Amsterdam, which hosted an important exhibition touching on international Futurism. His painting Boomgaard (Orchard) from 1913 is often cited as a prime example of his engagement with Cubism, featuring fragmented trees and landscape elements rendered in dynamic, angular planes of colour, creating a rhythmic and vibrant composition that stands as a landmark of Dutch Cubism.

Expressionism and the Bergen School

Following his intense engagement with Cubism and Futurism, Gestel's style shifted again around 1914-1915, moving towards Expressionism. This transition coincided with the outbreak of World War I, which forced many Dutch artists, including Gestel and Mondrian, who were abroad, to return to the Netherlands. Isolated from the Parisian scene, Dutch artists developed their own responses to modernism. Gestel became associated with the Bergen School (Bergense School), a group of artists centred around the village of Bergen in North Holland.

The Bergen School represented a Dutch variant of Expressionism. While influenced by French Fauvism and Cubism, as well as German Expressionism (groups like Die Brücke with Ernst Ludwig Kirchner or Der Blaue Reiter), it developed its own distinct character. Bergen School paintings typically feature figurative subjects – landscapes, portraits, still lifes – rendered with bold, often dark outlines, simplified forms, a somber or earthy colour palette (a departure from Gestel's earlier Luminist brilliance), and an emphasis on conveying mood and emotion rather than objective reality. The style is often described as having a certain robustness and connection to the Dutch landscape and character.

Key figures of the Bergen School included Charley Toorop (daughter of Jan Toorop), Matthieu Wiegman, Piet Wiegman, and Arnout Colnot. Gestel was a central figure during his time associated with the group. His works from this period, such as Boerderij in de Beemster (Farm in Beemster), exemplify the Bergen School style. These paintings often feature strong, angular forms derived from his Cubist experiments but imbued with a darker, more emotionally charged atmosphere. The brushwork is vigorous and expressive, contributing to the overall intensity of the image. Gestel's Expressionist phase demonstrated his ability to adapt international trends to a personal and recognizably Dutch sensibility.

Versatility Beyond the Canvas

While primarily known as a painter, Leo Gestel's artistic output was remarkably diverse. He was a skilled draftsman and printmaker, proficient in techniques like etching, woodcut, and lithography. These mediums allowed him to explore different textural effects and compositional possibilities, often complementing his work in painting. His drawings, in particular, reveal a fluid and confident line, capable of capturing movement and character with great economy. Many preparatory sketches for his paintings survive, offering insights into his working process.

Gestel also applied his talents to the graphic arts and illustration. During World War I, when the art market was difficult, he undertook commercial commissions, including designing posters and advertisements. Notably, he created illustrations for the Philips company, demonstrating his ability to adapt his modern style to commercial purposes without sacrificing artistic integrity. His illustrations often retained the bold lines and simplified forms characteristic of his paintings, sometimes incorporating elements of humour or caricature.

Furthermore, Gestel experimented with mural painting, although fewer examples of this aspect of his work survive. His willingness to work across different media and contexts underscores his broad conception of art's role and his versatility as a creator. This engagement with applied arts aligns him with other modern artists who sought to break down the traditional hierarchy between fine art and design, believing that modern aesthetics could permeate all aspects of life. His diverse activities highlight a restless creativity that constantly sought new avenues for expression.

Challenges and Later Years

Leo Gestel's career was not without significant setbacks. A major blow occurred in 1929 when a devastating fire swept through his studio in the Blienwijk neighbourhood of Blaricum, where he had settled. The fire destroyed a large portion of his work, including many paintings and drawings accumulated over years. This catastrophic event represented not only a huge personal and financial loss but also a tragic erasure of a significant part of his artistic legacy. Friends and patrons rallied to support him, but the loss undoubtedly cast a shadow over his later years.

Despite this tragedy, Gestel continued to work, though his output may have slowed. He spent time living and working in various locations, including Blaricum and his final residence in Hilversum. His later work saw a partial return to more recognizable forms, though always filtered through his modernist sensibility. He continued to paint landscapes, still lifes, and portraits, often characterized by a lyrical quality and a continued mastery of colour, perhaps tempered by the experiences of his life.

In his final years, Gestel suffered from a serious stomach ailment that required hospitalization. Even during this difficult period, his creative spirit remained active. One poignant anecdote relates to a work titled De uitgaande dans (The Leaving Dance), which he reportedly painted for his physician, Dr. W.A. Boekelman, perhaps as a token of gratitude or a reflection on his condition. Leo Gestel passed away from his illness on November 26, 1941, at the age of 60, leaving behind a rich and complex body of work that had significantly shaped the course of Dutch modern art.

Legacy and Influence

Leo Gestel's contribution to Dutch art history is undeniable. He was a key transitional figure, bridging the gap between late 19th-century Impressionism and the full flowering of 20th-century Modernism in the Netherlands. His relentless experimentation across Luminism, Cubism, Futurism, and Expressionism provided a vital Dutch interpretation of international avant-garde movements. Alongside Mondrian and Sluijters, he helped liberate Dutch painting from the constraints of academic realism and the Hague School's dominance, paving the way for subsequent generations.

His influence can be seen in his role within specific movements like Dutch Luminism and the Bergen School, where he was a leading practitioner. His ability to synthesize diverse influences into a personal style, characterized by strong colour, dynamic composition, and expressive power, made him a model for other artists seeking their own modern voice. While perhaps not achieving the same level of international fame as his contemporary Piet Mondrian (who pursued abstraction to its radical conclusion with De Stijl), Gestel's work remains highly regarded within the Netherlands and among scholars of European modernism.

Today, Leo Gestel's works are held in major Dutch museum collections, including the Kunstmuseum Den Haag, the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, the Van Gogh Museum (which holds works by contemporaries), the Frans Hals Museum in Haarlem, and the Kröller-Müller Museum. His archives, providing invaluable material for research, were acquired by the RKD – Netherlands Institute for Art History in the 1960s. His hometown of Woerden honours him with the Gestel Promenade, featuring reproductions of his work. His paintings continue to be sought after by collectors, achieving significant prices at auction, attesting to his enduring appeal and historical importance. Other Dutch modernists like Jacoba van Heemskerck and Bart van der Leck also navigated this period of intense change, further highlighting the vibrant artistic milieu Gestel inhabited.

Conclusion

Leo Gestel was more than just a painter; he was an explorer on the frontiers of modern art in the Netherlands. His journey from the artistic environment of his family through the academies of Amsterdam, the crucible of Parisian avant-gardism, and the development of distinctly Dutch modern movements like Luminism and the Bergen School, reflects the dynamic trajectory of European art in the early 20th century. His willingness to embrace and adapt diverse styles – Impressionism, Pointillism, Fauvism, Cubism, Futurism, Expressionism – resulted in a body of work characterized by its energy, vibrant colour, and expressive depth.

Though his career faced challenges, including the devastating studio fire of 1929, Gestel's dedication to his craft remained unwavering. His legacy lies not only in his influential paintings but also in his versatile work across drawing, printmaking, and illustration. As a central figure alongside Piet Mondrian and Jan Sluijters, Leo Gestel played a pivotal role in defining Dutch Modernism, leaving an indelible mark on the nation's artistic heritage and ensuring his place as one of its most significant early modern masters. His work continues to resonate, offering a compelling vision of a world perceived through the transformative lens of light, colour, and modern sensibility.