Alice Bailly stands as a significant, though sometimes overlooked, figure in the vibrant tapestry of early 20th-century European art. A Swiss painter, draughtswoman, and multimedia artist, Bailly (1872-1938) navigated the tumultuous currents of modernism, actively engaging with its key movements and forging a unique artistic identity. Her career, spanning from the lingering influences of Post-Impressionism to the radical experiments of Cubism, Fauvism, Futurism, and Dadaism, reflects a relentless pursuit of innovation and a distinctive sensitivity to color and form. As one of the few prominent female artists in the male-dominated avant-garde circles of Paris, her journey and contributions offer valuable insights into the era's artistic evolution.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening in Switzerland

Born in Geneva, Switzerland, in 1872, Alice Bailly emerged from a modest background. Her father worked for the postal service, and her mother was a German teacher. Despite the lack of significant wealth, the family environment seemingly fostered an appreciation for culture and learning. Bailly received her formal artistic training in Geneva, attending classes specifically for women at the École des Beaux-Arts. During this formative period, she likely absorbed the prevailing academic traditions but also encountered the influences of late 19th-century movements, such as Symbolism and the decorative impulses of Art Nouveau, which were filtering into Swiss art circles through figures like Ferdinand Hodler.

Her early work, though less radical than her later output, already hinted at a strong sense of design and an interest in expressive potential. Switzerland, while geographically central, was somewhat peripheral to the main artistic revolutions brewing in Paris. For an ambitious young artist like Bailly, the allure of the French capital, the undisputed center of the art world, proved irresistible. She sought a more dynamic environment where she could directly engage with the latest artistic developments.

The Parisian Crucible: Immersion in the Avant-Garde

In 1904, Bailly made the pivotal decision to move to Paris. This relocation marked the true beginning of her engagement with modernism. Paris in the early 1900s was a melting pot of artistic experimentation. Bailly quickly integrated into the city's avant-garde milieu, establishing friendships and professional connections with artists who would shape the course of modern art. She became acquainted with key figures residing and working in Montparnasse and Montmartre, absorbing the energy of studios, cafés, and galleries where new ideas were fiercely debated and displayed.

Among her notable acquaintances were Fauvist painters like Kees van Dongen and Othon Friesz, whose bold use of non-naturalistic color undoubtedly made an impression. More significantly, she formed close ties with artists associated with the burgeoning Cubist movement. Her circle included Juan Gris, Francis Picabia, Marie Laurencin, Albert Gleizes, and Jean Metzinger. Laurencin, another prominent female artist navigating the Parisian scene, became a particularly close friend, sharing experiences and likely offering mutual support. This network provided Bailly with direct exposure to the radical formal experiments that were challenging centuries of representational tradition.

Embracing Cubism and Futurism: Deconstructing Form and Motion

Bailly's arrival in Paris coincided with the explosive emergence of Fauvism (around 1905) and the subsequent development of Cubism, pioneered by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque around 1907. Bailly proved receptive to these new visual languages. She began incorporating elements of Cubism into her work, particularly its fragmentation of objects, flattening of space, and adoption of multiple viewpoints. Unlike the often-monochromatic palette of early Analytic Cubism practiced by Picasso and Braque, Bailly, perhaps influenced by her Fauvist contacts and her own innate color sense, retained a vibrant chromatic range.

Her engagement with Cubism is evident in works like Cemetery (1913), where architectural forms are fractured and rearranged into dynamic geometric planes. She exhibited alongside the Cubists, including at the influential Salon des Indépendants and the Salon d'Automne. Her association with Gleizes and Metzinger, authors of the first major treatise on Cubism, Du "Cubisme" (1912), placed her firmly within the movement's orbit, even as she developed her own interpretation.

Simultaneously, Bailly absorbed the influence of Italian Futurism, a movement championed by artists like Umberto Boccioni, Giacomo Balla, and Gino Severini. Futurism celebrated dynamism, speed, technology, and the sensory overload of modern life. This resonated with Bailly, leading her to incorporate a sense of movement and energy into her compositions. Works like Equestrian Fantasy (also known as Fantaisie équestre, 1913) combine Cubist fragmentation with Futurist lines of force and dynamism, capturing the energy of the subject rather than just its static appearance. A Chilly Morning in Luxembourg (1920) also displays Futurist sensibilities in its depiction of urban bustle.

Color and Expression: The Fauvist Strain

While deeply engaged with the structural innovations of Cubism and the dynamism of Futurism, Bailly never abandoned her commitment to color as a primary expressive tool. The influence of Fauvism, with its emphasis on subjective, intense, and often arbitrary color, remained a constant thread in her work. Artists like Henri Matisse and André Derain had demonstrated color's power to convey emotion and structure a composition independently of realistic depiction.

Bailly embraced this freedom, employing bold reds, oranges, blues, and greens to animate her canvases. This is particularly striking in her portraits and figurative works. At Leisure (1922), for instance, uses vibrant color fields and expressive brushwork that owe as much to Fauvism and German Expressionism (perhaps encountered through Swiss connections or Parisian exhibitions) as to Cubist structure. Her palette remained consistently brighter and more varied than that of many of her strictly Cubist contemporaries.

Innovation in Medium: The "Wool Paintings"

One of Alice Bailly's most distinctive contributions was her invention of "wool paintings" or tableaux-laine. Developed around 1913-1914, this technique involved affixing short strands of colored yarn or wool onto a support (canvas or board) to create images. These works ingeniously blended craft traditions with avant-garde aesthetics. The strands of wool mimicked the short, distinct brushstrokes of Impressionism or Pointillism but translated them into a tactile, textile medium.

The tableaux-laine allowed Bailly to explore texture and color in novel ways. They can be seen as a form of collage, related to the papiers collés being developed by Picasso and Braque, but with a unique material sensibility. This technique blurred the lines between fine art (painting) and applied art or craft (textiles), a radical gesture at a time when such hierarchies were strongly enforced. These wool paintings often depicted modern subjects, integrating her Cubist and Futurist interests with this innovative medium. This technique garnered attention and was praised by critics like Guillaume Apollinaire, a key supporter and theorist of the Parisian avant-garde.

Exhibitions, Recognition, and Criticism

Bailly was an active participant in the Parisian exhibition circuit, a crucial arena for avant-garde artists seeking recognition. She showed her work regularly at the Salon des Indépendants (from 1906), the Salon d'Automne (from 1912), the Salon de Tuileries, and various gallery exhibitions in Paris, Zurich, and elsewhere. Her inclusion in the 1912 Salon d'Automne's Cubist room (Salle XI) alongside Gleizes, Metzinger, Picabia, and Laurencin cemented her position within the movement.

Her work received positive attention, notably from Apollinaire, who admired her originality and color sense. However, the avant-garde path was not without its challenges. Like many modernists, she faced criticism from more conservative quarters. Her innovative tableaux-laine, while praised by some, were likely viewed with skepticism by others due to their unconventional medium. The very act of exhibiting challenging, non-traditional work was a statement in itself, contributing to the ongoing dialogue about the nature and direction of modern art.

Wartime Return and the Dada Connection

The outbreak of World War I in 1914 forced many foreign artists, including Bailly, to leave Paris. She returned to her native Switzerland, initially settling in Geneva before moving to Lausanne in 1923, where she would remain for the rest of her life. Switzerland's neutrality made it a refuge for artists, writers, and intellectuals from across Europe. Zurich, in particular, became the birthplace of the Dada movement at the Cabaret Voltaire in 1916, spearheaded by figures like Tristan Tzara, Hugo Ball, Jean Arp, and Sophie Taeuber-Arp.

While based primarily in the French-speaking part of Switzerland, Bailly was aware of and peripherally connected to the Dada spirit of anti-art, absurdity, and protest against the war and bourgeois values. Her own work, with its embrace of unconventional materials (tableaux-laine) and its challenge to traditional aesthetics, shared some common ground with Dadaist experimentation. Although not a central figure in Zurich Dada, her avant-garde credentials and innovative techniques aligned her with the movement's broader rejection of artistic conventions. She maintained connections with the Swiss art world and visiting émigré artists throughout the war years.

Later Career: Synthesis and Major Commissions

After the war, Bailly continued to develop her style, synthesizing the various influences she had absorbed. Her work from the 1920s and 1930s often shows a consolidation of Cubist structure, Futurist dynamism, and Fauvist color, applied to portraits, landscapes, and still lifes. She remained committed to a modern aesthetic, even as some artists in Europe experienced a "return to order" (retour à l'ordre) favoring more classical forms.

A significant achievement of her later career was the commission in 1936 to create large-scale murals for the foyer of the Municipal Theatre of Lausanne. This major public project allowed her to work on an ambitious scale, translating her vibrant style into monumental compositions. The murals, depicting themes related to theatre and music, represent a culmination of her artistic journey, showcasing her mastery of color, form, and dynamic composition. Sadly, her work on this project was cut short by illness.

Notable Works: A Glimpse into Bailly's Vision

Alice Bailly's oeuvre is diverse, but several works stand out as particularly representative of her style and innovations:

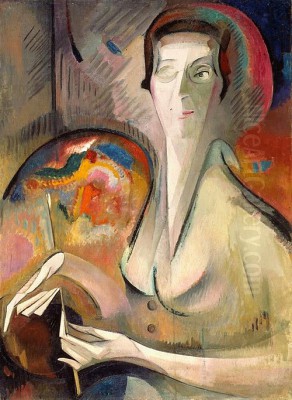

Self-Portrait (1917): Considered one of her masterpieces, this work exemplifies her mature style. It blends Cubist fragmentation of the face and background with expressive, Fauvist-inspired colors (vivid reds, oranges, blues) and a dynamic composition. The confident gaze and modern presentation challenge traditional depictions of female artists.

Equestrian Fantasy (1913): A prime example of her engagement with both Cubism and Futurism. The horse and rider are fractured into geometric planes, conveying a powerful sense of energy and movement characteristic of Futurist aesthetics.

Cemetery (1913): A Cubist landscape where buildings and space are deconstructed and reassembled, demonstrating her understanding of the movement's core principles while maintaining a degree of legibility and strong design.

Fountain in a Roman Garden: This work showcases her move towards greater abstraction, using form and color to evoke the essence of the subject rather than a literal depiction.

Arthur Honegger and “David the King”: A portrait reflecting her interest in contemporary cultural figures (Honegger was a prominent Swiss composer), interpreted through her unique modernist lens.

Wool Paintings (various, c. 1913-1920s): This body of work is significant not just for individual pieces but for the innovative technique itself, representing her unique contribution to mixed-media art.

Legacy and Historical Evaluation

Alice Bailly died of tuberculosis in Lausanne in 1938, shortly after completing preliminary work on the theatre murals. Her position in art history is that of a significant participant in European modernism and a key figure in the Swiss avant-garde. She successfully navigated multiple major art movements, developing a personal synthesis characterized by vibrant color, dynamic composition, and formal experimentation.

Her invention of the tableaux-laine marks her as an innovator in materials and techniques. As a woman artist active in the heart of the Parisian avant-garde, she broke barriers and contributed a distinct perspective. While perhaps not achieving the household-name status of Picasso, Matisse, or her friend Juan Gris, her work was recognized and respected within modernist circles. Figures like Apollinaire saw her importance early on.

In recent decades, there has been renewed interest in Bailly's work, partly fueled by a broader reassessment of women artists' contributions to modernism. Exhibitions and scholarship have helped to bring her achievements to a wider audience, securing her place as a pioneering Swiss modernist whose art bridged national borders and artistic movements. Her legacy lies in her bold embrace of modernity, her innovative spirit, and the vibrant, energetic body of work she created against the backdrop of a rapidly changing world. She remains an inspiration for her artistic courage and her unique fusion of color, form, and innovative technique.