Hugo van der Goes stands as one of the most significant and enigmatic painters of the Early Netherlandish period, active during the latter half of the 15th century. Though his documented career was relatively short, spanning roughly from 1467 until his death in 1482, his artistic output was intensely powerful, characterized by monumental scale, profound psychological insight, innovative compositions, and a distinctive use of color. His work bridged the meticulous realism of his predecessors with a new, deeply felt emotional intensity that left an indelible mark on both Northern European and Italian Renaissance art. Despite his contemporary renown, much of his life, particularly his later years marked by spiritual turmoil, remains shrouded in a degree of mystery, adding to the fascination he continues to hold for art historians.

Early Life and Emergence in Ghent

The precise birthdate and origins of Hugo van der Goes are not definitively recorded, though scholarly consensus places his birth around 1435 to 1440. Ghent is widely accepted as his likely place of birth or at least his primary city of activity. Historical records first firmly place him in Ghent in 1467, the year he was admitted as a master into the painters' guild of Saint Luke. His entry into the guild was sponsored by several established figures, including the prominent painter Joos van Wassenhove, later known as Justus of Ghent (or Joos van Gent), indicating that Van der Goes was already a painter of some standing and skill by this time.

His rapid ascent within the Ghent artistic community is notable. He was frequently commissioned for significant civic and religious projects. From 1468 onwards, he received numerous commissions from the city of Ghent for ephemeral works such as decorations for papal envoys, ducal entries (like that of Charles the Bold and Margaret of York in 1468), and other public festivities. These tasks, though not surviving, underscore his esteemed position. His involvement in the Ghent guild was substantial; he served as its dean from 1473/74 to 1476, a role signifying the high regard in which his peers held him. This period likely saw the creation of some of his early, now lost or unattributed, panel paintings.

The artistic environment of Ghent, and indeed the broader Burgundian Netherlands, was rich and competitive. Van der Goes would have been acutely aware of the legacy of masters like Jan van Eyck and Rogier van der Weyden, whose innovations in oil painting technique, realism, and emotional depth had set a high standard. While Van der Goes absorbed these influences, he forged a distinctly personal style, marked by a more overt and sometimes unsettling psychological intensity.

The Monumental Vision: The Portinari Altarpiece

The cornerstone of Hugo van der Goes's oeuvre and the work upon which much of his fame rests is the Portinari Altarpiece. Commissioned by Tommaso Portinari, an Italian banker representing the Medici family in Bruges, this massive triptych, depicting the Adoration of the Shepherds in its central panel, was destined for the Portinari family chapel in the church of Sant'Egidio in Florence. Its arrival in Florence around 1483, shortly after Van der Goes's death, created a sensation among Italian artists.

The central panel, "The Adoration of the Shepherds," is a breathtaking display of Van der Goes's genius. The Virgin Mary, rendered with a solemn, introspective beauty, kneels in adoration before the Christ Child, who lies on the bare ground, radiating a divine light. Saint Joseph, depicted with a rugged, earnest piety, stands to her side. Surrounding them are angels, their rich brocades and varied expressions adding to the scene's opulence and emotional range. Most striking, however, are the shepherds. Bursting into the scene from the right, their faces are studies in rustic realism, etched with awe, wonder, and a raw, unvarnished humanity. Their coarse features and animated gestures contrast sharply with the refined grace of the Virgin and angels, yet they are rendered with profound empathy.

The side wings depict the Portinari family with their patron saints. The left wing shows Tommaso Portinari and his sons, Antonio and Pigello, kneeling under the gaze of Saint Anthony Abbot and Saint Thomas. The right wing presents Maria Baroncelli, Tommaso's wife, with their daughter Margherita, accompanied by Saint Mary Magdalene and Saint Margaret. The scale of these donor figures is unusually large relative to the saints, a testament to their status and perhaps Van der Goes's innovative approach to donor portraiture. The meticulous rendering of textures – velvets, furs, jewels, and skin – is a hallmark of Netherlandish painting, executed here with consummate skill.

The landscape backgrounds of the wings are continuous, depicting scenes related to the central theme: the Journey of the Magi, the Annunciation to the Shepherds, and the Flight into Egypt, all rendered with atmospheric perspective and exquisite detail. Symbolism abounds: the sheaf of wheat alludes to Bethlehem ("house of bread") and the Eucharist; the columbine flowers symbolize the Holy Spirit's sorrow; the irises and lilies represent Christ's Passion and Mary's purity, respectively. The somber, almost melancholic, mood that pervades the altarpiece, despite its celebratory theme, is characteristic of Van der Goes's sensibility.

Impact in Florence and on Italian Art

The arrival of the Portinari Altarpiece in Florence was a pivotal moment. Italian artists, accustomed to the more idealized forms and classical harmonies of their own Renaissance, were struck by its intense realism, particularly in the depiction of the shepherds, the rich textures, and the emotive power of the figures. Artists like Domenico Ghirlandaio were profoundly influenced, as seen in his "Adoration of the Shepherds" (Sassetti Chapel, Santa Trinita, 1485), which directly quotes Van der Goes's rustic shepherd types.

Other Florentine masters, including Leonardo da Vinci, Filippino Lippi, and Lorenzo di Credi, are also thought to have studied the altarpiece closely. The Netherlandish oil technique, with its capacity for luminous color and minute detail, was greatly admired. Van der Goes's ability to convey deep psychological states and a palpable sense of spiritual drama resonated with the evolving artistic concerns in Italy. The Portinari Altarpiece thus became a crucial conduit for the exchange of artistic ideas between North and South, demonstrating the international prestige of Netherlandish painting.

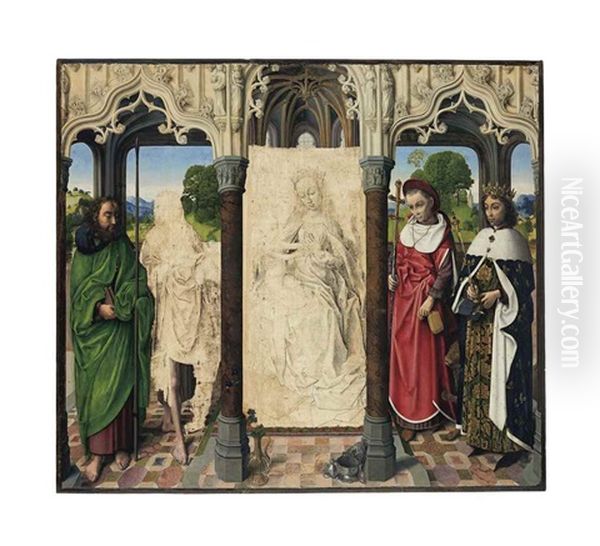

Other Key Works and Stylistic Traits

While the Portinari Altarpiece is his most famous work, several other paintings are securely attributed to Van der Goes or are central to understanding his artistic development.

The Monforte Altarpiece (Gemäldegalerie, Berlin), likely an earlier work, depicts the Adoration of the Magi. Though only the central panel survives, it showcases Van der Goes's skill in complex group compositions and rich color harmonies. The figures possess a sculptural monumentality, and the varied expressions of the Magi and their retinue reveal his burgeoning interest in psychological characterization.

The Death of the Virgin (Groeningemuseum, Bruges) is a profoundly moving and unsettling work, likely from his later period, possibly created after he had entered the monastery. The Virgin lies on her deathbed, surrounded by the Apostles, each reacting with a distinct and intensely personal grief. The cramped space, the dissonant colors (particularly the blues and reds), and the almost distorted expressions of the Apostles convey a palpable sense of anguish and spiritual crisis. The figure of Christ appearing above to receive his mother's soul offers a glimmer of divine solace, but the overwhelming impression is one of human suffering and emotional turmoil. This work is often seen as reflecting Van der Goes's own mental state.

Two wings of a diptych, known as the Vienna Diptych (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna), depict "The Fall of Man" and "The Lamentation." "The Fall" shows Adam and Eve with a uniquely reptilian serpent, while "The Lamentation" is a scene of raw, almost unbearable grief, with Christ's contorted body and the anguished faces of Mary and John. The stark emotionalism and dramatic intensity are characteristic of his late style.

Smaller devotional panels, such as the Adoration of the Magi (Friedsam Altarpiece) (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York), and portraits, like the Portrait of a Man (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York), further demonstrate his versatility. His portraits are notable for their psychological penetration and unsparing realism.

Van der Goes's style is characterized by several key features:

Monumentality: His figures often possess a weighty, sculptural quality, even in smaller works.

Psychological Depth: He excelled at conveying complex emotional states, from quiet introspection to intense anguish.

Realistic Detail: While rooted in the Netherlandish tradition of meticulous observation, his realism is often imbued with a heightened emotional charge.

Innovative Composition: He experimented with spatial arrangements and figure groupings to enhance dramatic impact.

Distinctive Color Palette: He often employed cool, somewhat somber colors, with striking juxtapositions that could create a sense of unease or heightened emotion. His blues are particularly noteworthy.

The Spiritual Crisis and Retreat to the Red Cloister

Around 1475 or shortly thereafter, at the height of his fame and artistic powers, Hugo van der Goes made the surprising decision to retire from secular life. He entered the Rode Klooster (Red Cloister), an Augustinian priory near Brussels, as a lay brother (frater conversus). The reasons for this retreat are not entirely clear but are generally attributed to a profound spiritual crisis and perhaps a pre-existing melancholic temperament. The Rode Klooster was part of the Windesheim Congregation, known for its association with the Devotio Moderna, a movement emphasizing personal piety and introspection.

Even within the monastery, Van der Goes was accorded special privileges. He was allowed to continue painting and received distinguished visitors, including Archduke Maximilian of Austria. However, his mental health appears to have deteriorated. A chronicle written by Gaspar Ofhuys, a fellow monk at the Rode Klooster (though written some years after Hugo's death and potentially biased), describes an acute episode of mental breakdown that occurred around 1480/81 during a journey back from Cologne. Van der Goes reportedly fell into a deep depression, believing himself to be damned and even attempting suicide. Ofhuys attributes his illness to his fame, the pressures of his art, and perhaps his consumption of wine.

Modern interpretations suggest he may have suffered from what we would now recognize as severe depression or another form of mental illness. His art, particularly later works like "The Death of the Virgin," is often analyzed through the lens of this personal turmoil, its intense emotionalism seen as a reflection of his inner state.

Relationships with Contemporaries and Influence

Hugo van der Goes was a significant figure within the Netherlandish artistic landscape. His relationship with Joos van Gent (Justus of Ghent) was clearly important in his early career in Ghent. Joos later traveled to Italy to work for Duke Federico da Montefeltro in Urbino, and some scholars have debated the extent of Van der Goes's possible influence on, or even collaboration with, Joos on the Urbino commissions, such as the "Communion of the Apostles."

He was a contemporary of other major Netherlandish painters. Hans Memling, active in Bruges, developed a serene and harmonious style that contrasts with Van der Goes's more intense emotionalism, yet both were masters of portraiture and religious narrative. Dieric Bouts, active in Leuven, was an older contemporary whose solemn, restrained style may have provided a point of departure for Van der Goes's more expressive figures. The legacy of Jan van Eyck and Rogier van der Weyden was, of course, foundational for all painters of this generation, including Van der Goes, who absorbed their technical mastery and pushed their expressive boundaries.

The influence of Van der Goes extended beyond his immediate circle and the Italian artists who saw the Portinari Altarpiece. His work was known and copied, and his approach to conveying psychological depth impacted later Northern artists. For instance, Geertgen tot Sint Jans, active in Haarlem, shows a similar sensitivity in the depiction of rustic figures and emotional nuance, suggesting an awareness of Van der Goes's innovations. Even the great German master Albrecht Dürer, on his journey to the Netherlands in 1520-21, noted seeing works by "master Hugo."

The French painter Jean Hey (often identified as the Master of Moulins), active in the late 15th century, also displays stylistic affinities with Van der Goes, particularly in the sculptural quality of his figures and his rich colorism, suggesting that Van der Goes's influence permeated various artistic centers. The anonymous master known as the Master of the View of Saint Gudule was also a contemporary active in Brussels, whose work reflects the broader trends of the period. Similarly, the Master of the Saint Ursula Legend in Bruges and the Master of the Saint Lucy Legend were creating their own distinct contributions to Netherlandish art during Hugo's lifetime.

Death and Posthumous Reputation

Hugo van der Goes died at the Rode Klooster in 1482, likely still grappling with his mental afflictions. He was buried within the cloister. Despite the tragic circumstances of his later years, his reputation as one of the preeminent painters of his time was firmly established. The Portinari Altarpiece, in particular, ensured his lasting fame, especially in Italy.

However, like many artists of his era, his name and the full extent of his oeuvre gradually faded from common knowledge over subsequent centuries, though his impact on art continued. It was not until the 19th century that art historians, through meticulous research of archival documents (such as the records of the Ghent guild and Ofhuys's chronicle) and stylistic analysis, began to reconstruct his career and firmly attribute key works to him. The Belgian historian Alphonse Wauters played a significant role in this rediscovery.

Today, Hugo van der Goes is recognized as a pivotal figure in 15th-century art. His ability to combine the meticulous realism of the Netherlandish tradition with an unprecedented emotional and psychological intensity gives his work a timeless power. He is often seen as an artist who pushed the boundaries of representation, exploring the depths of human experience with an unflinching, empathetic gaze. His life story, with its dramatic turn towards spiritual crisis and mental anguish, has also contributed to his image as a "mad genius," a romantic notion that, while perhaps an oversimplification, highlights the profound connection between his personal struggles and the deeply affecting nature of his art.

The Enduring Enigma and Legacy

Hugo van der Goes remains an artist of compelling complexity. His works are not merely technical marvels of oil painting; they are profound meditations on faith, humanity, and the human condition. The tension between the sacred and the profane, the spiritual and the worldly, is palpable in his art. His shepherds in the Portinari Altarpiece are not idealized pastoral figures but real, weather-beaten men experiencing a moment of divine revelation. His grieving Apostles in "The Death of the Virgin" are not stoic saints but individuals overwhelmed by loss.

This raw emotional honesty, combined with his technical brilliance, is what makes his art so enduring. He expanded the expressive range of Netherlandish painting, demonstrating its capacity to convey not just the outward appearance of things but also the inner lives of individuals. His influence, both direct and indirect, was significant, contributing to the rich artistic dialogue between Northern and Southern Europe during the Renaissance.

The limited number of surviving works securely attributed to him, coupled with the fragmentary knowledge of his life, particularly his inner world, ensures that Hugo van der Goes will continue to be a subject of scholarly debate and fascination. He stands as a testament to the power of art to transcend personal suffering and to communicate universal human experiences with enduring resonance, a true master whose legacy continues to inspire and move viewers centuries after his death. His exploration of the human psyche within religious narratives paved the way for later artists who sought to imbue their work with similar emotional depth, from the High Renaissance masters to figures like Caravaggio with his dramatic realism, and even much later, artists like Vincent van Gogh, who also wrestled with intense emotions and sought to express them through their art.