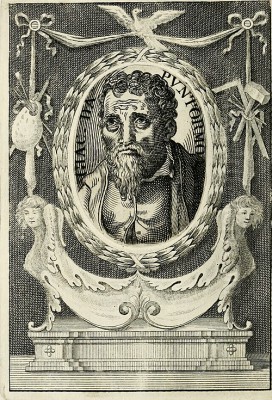

Jacopo Carucci, known to history as Jacopo da Pontormo (1494-1557), stands as one of the most significant and individualistic painters of the Florentine School during the Italian Renaissance. Born in the small town of Pontorme, near Empoli in Tuscany, he rose from provincial origins to become a central figure in the development of Mannerism, a style that consciously diverged from the harmonious ideals of the preceding High Renaissance. Pontormo's art is characterized by its emotional intensity, unconventional compositions, vibrant and often unsettling color palettes, and a profound exploration of human psychology. His life, marked by personal eccentricities and periods of isolation, seems intrinsically linked to the anxious beauty and spiritual depth found in his work, leaving a complex and enduring legacy.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Florence

Jacopo Carucci's early life was touched by loss. His father, Bartolommeo di Jacopo di Martino Carucci, was himself a painter, providing an initial connection to the art world, but he died when Jacopo was young. His mother also passed away not long after, and following her remarriage and subsequent death, the orphaned Jacopo was eventually raised by his grandmother and later likely supported by relatives or guardians in Florence. This early instability may have contributed to the sensitivity and perhaps the underlying melancholy often perceived in his later work and personality.

His artistic journey began in Florence, the vibrant heart of the Renaissance. Pontormo's talent must have been evident early on, as he passed through the workshops of several leading masters. According to the art historian Giorgio Vasari, Pontormo had brief stints with the legendary Leonardo da Vinci and also studied with Mariotto Albertinelli and Piero di Cosimo, known for his imaginative and sometimes eccentric mythological scenes. Each of these masters likely imparted different skills and perspectives, contributing to the young artist's formation.

The most significant apprenticeship, however, was with Andrea del Sarto, a leading painter in Florence known for his graceful figures, harmonious compositions, and mastery of color and sfumato. Pontormo entered Sarto's workshop around 1512, working alongside other talented pupils like Rosso Fiorentino. While initially absorbing Sarto's influential style, Pontormo soon began to assert his own artistic voice, moving away from the classical balance of his master towards a more expressive and unconventional approach. By 1516, he was registered as an independent master in the Florentine painters' guild, the Arte dei Medici e Speziali, signaling the formal start of his independent career.

The Emergence of a Unique Style: Early Mannerism

Pontormo's departure from the High Renaissance norms established by artists like Raphael and his own teacher, Andrea del Sarto, was not abrupt but gradual, yet decisive. He, along with contemporaries like Rosso Fiorentino, began to explore artistic avenues that prioritized subjective expression, emotional intensity, and formal experimentation over classical harmony and naturalism. This burgeoning style, later termed Mannerism, reflected a period of social, political, and religious upheaval in Italy.

A key influence on Pontormo's developing style was Michelangelo. The powerful dynamism, complex poses (figura serpentinata), and emotional weight of Michelangelo's figures, particularly those on the Sistine Chapel ceiling, resonated deeply with Pontormo. He adapted this influence not by mere imitation, but by integrating it into his own increasingly personal vision, often pushing anatomical elongation and contortion even further.

Another crucial, perhaps surprising, influence came from Northern European art, specifically the prints of Albrecht Dürer and Lucas van Leyden. Pontormo studied these prints intently, particularly during his work at the Certosa del Galluzzo monastery outside Florence in the early 1520s. The sharp linearity, angular forms, detailed realism, and intense emotionalism of Northern art offered an alternative to the softer, idealized forms of the Italian High Renaissance, and elements of this can be seen in the heightened drama and sometimes starker quality of Pontormo's work from this period onwards.

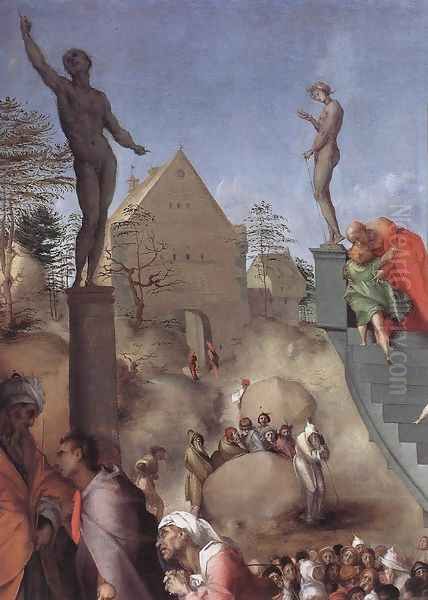

His early independent works began to showcase these emerging traits. The Joseph in Egypt panel (c. 1515-18), part of a series for the Borgherini bedchamber, already displays a crowded composition, illogical spatial arrangements, figures in varied and dynamic poses, and bright, almost discordant colors – hallmarks of his developing Mannerist sensibility. The Madonna and Saints altarpiece for the church of San Michele Visdomini (1518) further demonstrates his move towards heightened emotionalism and a departure from Sarto's serene classicism, with figures displaying a palpable sense of psychological unease.

Major Commissions and Masterpieces

Pontormo's career unfolded through a series of significant commissions, primarily in Florence and its surroundings, allowing him to refine and express his unique artistic vision. His works often challenge viewers with their complexity and emotional depth.

One notable early commission was the fresco decoration of the main salon at the Medici Villa Poggio a Caiano (c. 1519-21). Here, Pontormo painted a lunette depicting the pastoral myth of Vertumnus and Pomona. While seemingly lighthearted, the work displays a sophisticated informality, naturalistic details, and a relaxed arrangement of figures that subtly departs from strict classical composition, hinting at his growing independence.

A period of intense creativity and stylistic development occurred during his work at the Certosa del Galluzzo (1523-1525), where he sought refuge during a plague outbreak in Florence. The frescoes depicting the Passion of Christ, heavily influenced by Dürer's prints, are marked by their stark emotionalism, angular figures, and dramatic intensity, showcasing his absorption of Northern Gothic sensibilities into his Florentine training.

Arguably Pontormo's most celebrated achievement is the decoration of the Capponi Chapel in the church of Santa Felicità in Florence (c. 1525-1528). Here, he created the stunning altarpiece, the Deposition from the Cross (or Lamentation), and the fresco of the Annunciation on the adjacent wall, along with roundels of the Evangelists in the pendentives (partially executed with his pupil Bronzino). The Deposition is a quintessential Mannerist masterpiece. It rejects traditional iconography – there is no cross, no defined landscape. Instead, a swirling vortex of brightly clad figures, seemingly weightless and suspended in grief, lowers the pale body of Christ. The colors are luminous and unconventional – pinks, blues, greens, oranges – creating an ethereal, otherworldly atmosphere. The figures' elongated limbs, anguished expressions, and precarious poses convey profound sorrow and spiritual turmoil.

Another key work is the Visitation (c. 1528-1529), painted for a church in Carmignano. This panel depicts the meeting of Mary and Elizabeth with an intense psychological connection. The four figures dominate the composition, clad in voluminous drapery of vibrant, almost electric colors. Their monumental forms, enigmatic expressions, and the strangely vacant background create a powerful and unsettling image of profound spiritual encounter.

Pontormo was also a highly accomplished portraitist. He moved beyond the idealized representations typical of the High Renaissance to capture the inner life and psychological nuances of his sitters. His portraits often convey a sense of melancholy, introspection, or aristocratic reserve. Notable examples include the posthumous Portrait of Cosimo de' Medici the Elder (c. 1519-20), the sensitive Portrait of a Halberdier (c. 1528-30), and portraits of the Medici dukes, such as the Portrait of Alessandro de' Medici (c. 1534-35). His approach contrasts with the serene confidence often seen in portraits by Raphael or the opulent textures favored by Titian, instead focusing on a more nervous, introspective energy.

The Late Period: San Lorenzo and the Diary

Pontormo's later career was dominated by a major, ultimately ill-fated, commission: the fresco decoration of the choir of the Basilica di San Lorenzo, the Medici family church in Florence. Begun around 1546 and consuming the last decade of his life, this vast project depicted scenes from Genesis, the Resurrection, and the Last Judgment. Pontormo worked largely in isolation, shielding his work from view.

Based on surviving preparatory drawings and descriptions by Vasari, the San Lorenzo frescoes were intensely complex, crowded with nude figures in dynamic, contorted poses, heavily influenced by Michelangelo's Last Judgment in the Sistine Chapel, which Pontormo had likely seen in Rome. The style seems to have pushed his Mannerist tendencies to an extreme, emphasizing spiritual drama and anatomical invention over narrative clarity.

Tragically, the frescoes were poorly received upon their unveiling after Pontormo's death. Giorgio Vasari, in his Lives of the Artists, famously criticized them for their confusing composition, lack of perspective, and overwhelming accumulation of nudes, deeming them a departure from decorum and artistic principles. The frescoes were eventually destroyed in 1738 during a remodeling of the choir, leaving only the drawings and Vasari's critical account as testaments to this ambitious final project.

During these last years (1554-1556), Pontormo kept a diary, known as Il Libro Mio ("My Book"). This remarkable document provides invaluable insights into the artist's daily life, preoccupations, and working methods during the San Lorenzo commission. He meticulously recorded his meals, his physical ailments, his anxieties about his health and work, the progress of his painting, and even sketches alongside the text. The diary paints a picture of a solitary, introspective, and somewhat neurotic individual, deeply absorbed in his art but also plagued by anxieties, including a profound fear of death. His reclusive habits intensified; Vasari recounts how Pontormo constructed his living quarters with a retractable ladder to ensure his privacy.

Relationships and Influence

Pontormo's artistic journey was shaped by his interactions with teachers, contemporaries, and his principal student. His relationship with Andrea del Sarto evolved from pupil-teacher to that of independent masters, with Pontormo ultimately forging a path distinctly different from Sarto's classicism.

His contemporary, Rosso Fiorentino, shared a similar starting point in Sarto's workshop and also became a key figure in early Mannerism. While sometimes seen as rivals, their styles developed along parallel yet distinct lines. Rosso often incorporated more angular, almost Gothic elements and a sharper emotional edge, while Pontormo explored more fluid lines and complex psychological states. Attribution debates surrounding works like the Capponi Chapel frescoes highlight their stylistic proximity during certain periods.

The most significant relationship was with Agnolo Bronzino. Bronzino entered Pontormo's workshop as a young boy (around 1515-17) and became not only his primary assistant and collaborator but also his adopted son and heir. Bronzino absorbed Pontormo's style deeply, and his early works are often difficult to distinguish from his master's. He assisted Pontormo on major projects, including the Certosa frescoes and the Capponi Chapel decorations. However, Bronzino eventually developed his own highly refined, elegant, and somewhat detached style of Mannerism, becoming the leading court painter to the Medici. While Bronzino's art achieved a cool, polished perfection, it lacked the raw emotional vulnerability often found in Pontormo's work.

Pontormo's influence extended beyond his direct circle. His innovative approach to composition, color, and emotional expression resonated with the broader Mannerist movement, potentially influencing artists like Parmigianino in their pursuit of elegant distortion and psychological intensity. While direct links are debated, some art historians have traced echoes of Pontormo's unsettling emotionalism and dramatic lighting in the works of later masters such as Tintoretto, and even, more distantly, in the psychological intensity of Caravaggio and the expressive freedom of Goya, as suggested by some interpretations of his long-term impact.

Critical Reception and Legacy

Pontormo's critical fortunes have fluctuated dramatically over the centuries. While recognized in his time, his highly personal and unconventional style also drew criticism. Vasari's negative assessment of the San Lorenzo frescoes significantly damaged Pontormo's posthumous reputation, contributing to a period of relative neglect. His work was often seen as eccentric, overly complex, or even decadent compared to the perceived clarity and harmony of the High Renaissance.

It was not until the late 19th and particularly the 20th century that Pontormo's art underwent a significant re-evaluation. Scholars and critics began to appreciate the originality, psychological depth, and formal innovation of his work. His role as a key pioneer of Mannerism was recognized, and his art was studied for its expressive power and its reflection of the spiritual and cultural anxieties of his time. Exhibitions and scholarly publications shed new light on his drawings, paintings, and the revealing contents of his diary.

Today, Pontormo is regarded as one of the most important and compelling artists of the 16th century. The controversies surrounding his style – its perceived artificiality versus its emotional authenticity – continue to fuel discussion. Speculation about his personality, his reclusiveness, and his possible psychological complexities, sometimes linked to interpretations of his diary and art, adds another layer to his enigmatic persona. His masterpieces, particularly the Deposition in the Capponi Chapel and the Visitation, are now considered iconic works of Mannerism, admired for their haunting beauty and profound emotional resonance.

Conclusion

Jacopo da Pontormo remains a fascinating and pivotal figure in Italian art history. He navigated the transition from the High Renaissance to Mannerism, forging a deeply personal style that prioritized emotional expression and formal experimentation over classical restraint. His works, characterized by elongated figures, swirling compositions, vibrant and often unusual colors, and intense psychological depth, offer a window into a complex artistic sensibility and a turbulent historical period. From his early training with Florence's masters to his solitary final years working on the lost San Lorenzo frescoes, Pontormo pursued a unique artistic path. Though sometimes misunderstood or criticized, his art endures, captivating viewers with its anxious beauty, spiritual intensity, and unforgettable vision. He stands as a testament to the power of individual expression within the rich tapestry of the Italian Renaissance.