Cosimo Tura, also known as Cosmè Tura, stands as a pivotal yet often enigmatic figure in the landscape of the Italian Renaissance. Active primarily in the latter half of the 15th century, Tura is widely recognized as the principal founder and one of the most distinctive voices of the School of Ferrara. His art, characterized by its sharp linearity, intense emotional expression, and a unique fusion of Gothic intensity with Renaissance humanism, carved a distinct niche for Ferrarese painting amidst the flourishing artistic centers of Florence and Venice. Working predominantly under the patronage of the Este dukes, Tura's output was diverse, ranging from grand altarpieces and intricate organ shutters to dynamic frescoes and designs for courtly ephemera. His style, though influential, remained uniquely his own, a testament to a singular artistic vision that continues to captivate and intrigue art historians and enthusiasts alike.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Padua

Cosimo Tura was born around 1430 in Ferrara, a city that would become inextricably linked with his artistic identity. His father, Domenico, was a shoemaker, a humble beginning for an artist who would later serve one of Italy's most illustrious courts. While details of his earliest training remain somewhat obscure, it is widely accepted that Tura's formative artistic experiences took place in Padua, a vibrant intellectual and artistic hub. There, he is believed to have been a pupil of Francesco Squarcione, a painter and collector of antiquities whose workshop was a crucible for many talents of the North Italian Renaissance.

Squarcione's teaching methods were unconventional; he encouraged his students to study from his collection of classical sculptures and casts, instilling in them a reverence for antiquity and a strong emphasis on draftsmanship and sculptural form. This environment undoubtedly shaped Tura's distinctive style, which often features figures with a chiseled, almost metallic quality. In Padua, Tura would have been exposed to the groundbreaking work of Donatello, the Florentine master sculptor, whose powerful and expressive figures, created during his Paduan sojourn (1443-1453), left an indelible mark on the artistic landscape of Northern Italy. The influence of Donatello's dramatic intensity and psychological depth can be discerned in Tura's own emotionally charged figures.

Furthermore, Tura's time in Padua likely brought him into contact with other emerging artists, including Andrea Mantegna, another of Squarcione's prominent pupils. Mantegna, who would become a towering figure of the Renaissance, shared with Tura an interest in classical antiquity, rigorous perspective, and a certain austerity of form. While their paths would diverge, the intellectual and artistic ferment of Padua provided a common foundation. The influence of other masters, such as the Sienese-trained painter Piero della Francesca, who worked in Ferrara for the Este court around mid-century, also played a role, particularly in terms of monumental compositions and the sophisticated use of perspective and light. Fra Angelico's work, with its clear light and devotional sincerity, may also have been a point of reference during Tura's developmental phase.

Court Painter to the Este Dukes of Ferrara

By 1456, Cosimo Tura had returned to his native Ferrara, and his career began to flourish under the patronage of the Este family, who ruled the city. In 1458, he was officially appointed court painter to Duke Borso d'Este, a position he would continue to hold under Borso's successor, Ercole I d'Este. This appointment was a significant milestone, providing Tura with a stable income, prestigious commissions, and the opportunity to contribute to the cultural splendor of one of Italy's most refined courts. The Este court was a center of humanism, literature, and art, and Tura's role extended beyond easel painting and altarpieces.

As court painter, Tura was responsible for a wide array of artistic endeavors. He designed tapestries, festival decorations, tournament paraphernalia, and even, it is said, gilded horse trappings and painted banners for state occasions. This versatility was typical for court artists of the period, who were expected to apply their skills to enhance every aspect of courtly life and ducal magnificence. While many of these ephemeral works have not survived, records attest to his active involvement in the visual culture of the Este court.

His primary focus, however, remained on more permanent works, including devotional paintings, altarpieces, and frescoes. He decorated ducal chapels and studioli, contributing to the lavish interiors of Este residences. His deep connection with the Este family ensured a steady stream of commissions and cemented his position as the leading painter in Ferrara for several decades. This patronage allowed him to develop his unique style without excessive compromise, though he undoubtedly adapted his work to the tastes and requirements of his patrons. The intellectual environment of the court, with its interest in classical literature, allegory, and chivalry, also likely informed the complex iconography found in some of his works.

The Distinctive Artistic Style of Cosimo Tura

Cosimo Tura's art is immediately recognizable for its highly individualistic style, a compelling synthesis of diverse influences forged into a unique visual language. His work is often described as intense, expressive, and even unsettling, departing significantly from the harmonious classicism that characterized much of the Florentine Renaissance or the coloristic richness of the Venetians.

A hallmark of Tura's style is his sharp, incisive linearity. Figures and drapery are often defined by crisp, almost metallic contours, giving them a sculptural, high-relief quality. This emphasis on line can create a sense of tension and energy within his compositions. His figures, while anatomically understood, are frequently elongated or contorted, their poses sometimes strained or angular, conveying a profound emotional or spiritual state. Faces are particularly expressive, often characterized by deep-set eyes, prominent cheekbones, and an air of asceticism or intense contemplation. This expressive intensity has led some scholars to see a lingering Gothic sensibility in his work, perhaps influenced by Northern European artists like Rogier van der Weyden, whose emotionally charged religious scenes were known in Italy.

Tura's use of color is equally distinctive. He often employed a palette of strong, sometimes cool and jewel-like hues, with unexpected juxtapositions that can create a vibrant, almost enameled surface. There is a certain hardness to his colors, eschewing the soft sfumato of Leonardo da Vinci or the atmospheric blending of Giovanni Bellini. Instead, Tura's colors contribute to the overall sense of heightened reality and emotional force. His draperies are often complex and voluminous, rendered with a metallic sheen, breaking into sharp, crystalline folds that catch the light in dramatic ways.

Architectural and landscape elements in Tura's paintings are frequently fantastical and imaginative. He created elaborate, often crumbling, classical structures and rocky, barren landscapes that add to the otherworldly atmosphere of his scenes. These settings are not merely backdrops but active participants in the narrative, echoing the emotional tenor of the figures. There is a meticulous attention to detail throughout his work, from the rendering of textures like metal and stone to the intricate ornamentation that often adorns his figures and settings. This combination of meticulous realism in detail with an overall fantastical conception is a key aspect of his unique vision. His style can be seen as a bridge, incorporating the decorative richness and expressive power of late Gothic art with the Renaissance concern for human anatomy, perspective, and classical form, albeit interpreted through a highly personal and often eccentric lens.

Masterworks of a Ferrarese Visionary

Cosimo Tura's oeuvre, though not vast due to losses over time, includes several masterpieces that exemplify his unique artistic contributions. Among his most celebrated early works are the organ shutters for the Ferrara Cathedral, completed in 1469. On one side, he depicted a dynamic and forceful Saint George and the Dragon, with the saint, clad in gleaming armor, heroically confronting the beast. The composition is filled with energy, the figures rendered with Tura's characteristic sculptural solidity. On the other side was an Annunciation, where the Virgin Mary and the Archangel Gabriel are portrayed with intense piety within an elaborate architectural setting. These large-scale works showcased Tura's mastery of dramatic composition and his ability to imbue traditional religious scenes with a powerful new expressiveness.

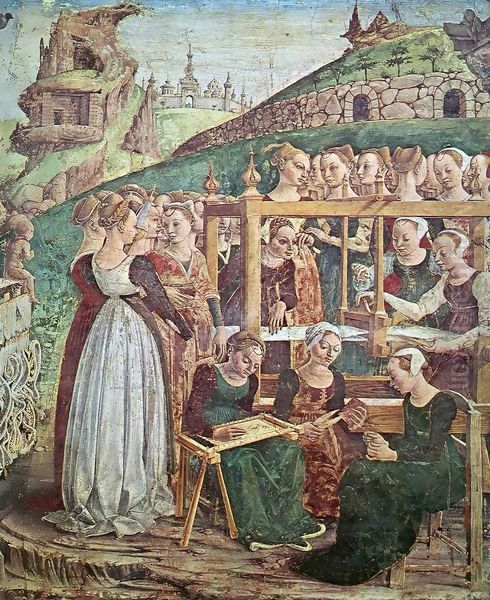

Another significant project was Tura's contribution to the fresco cycle in the Salone dei Mesi (Hall of the Months) at the Palazzo Schifanoia in Ferrara, undertaken for Duke Borso d'Este around 1469-1470. While Francesco del Cossa and Ercole de' Roberti were responsible for other sections, Tura is credited with designing the overall scheme and painting some of the allegorical figures and scenes, such as those for the month of March, depicting the Triumph of Minerva and Borso d'Este engaged in acts of governance and justice. These frescoes, with their complex astrological and mythological symbolism, are a testament to the sophisticated intellectual life of the Este court and Tura's ability to translate complex allegories into compelling visual narratives.

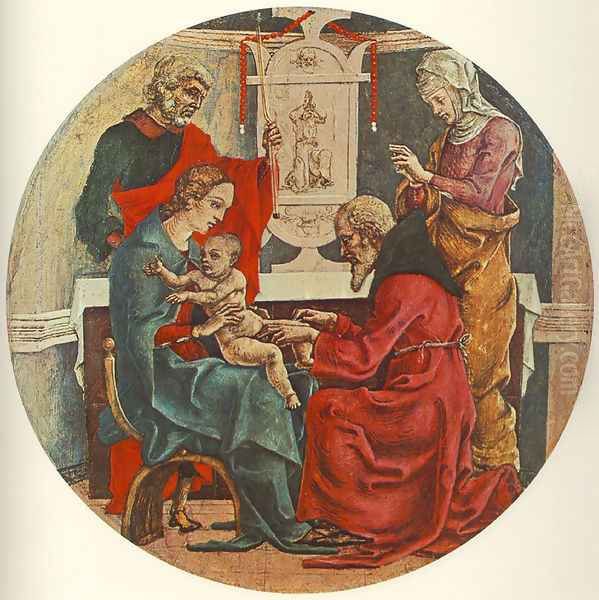

The Roverella Altarpiece, created in the 1470s for the church of San Giorgio fuori le Mura in Ferrara, was another major commission. Though now dismembered and its panels scattered across various museums, its surviving fragments attest to its original grandeur. The central panel, Madonna and Child Enthroned with Angels, now in the National Gallery, London, shows the Virgin and Child with Tura's characteristic intensity, surrounded by musical angels whose forms are both elegant and slightly unsettling. Perhaps the most emotionally powerful fragment is the Pietà, now in the Museo Correr, Venice. This depiction of the dead Christ supported by the Virgin Mary is a harrowing image of grief, rendered with Tura's typical angularity and expressive force, the figures seemingly carved from stone, their sorrow palpable.

Other notable works include A Muse (Calliope?), also in the National Gallery, London (sometimes referred to as Spring or an allegorical figure). This enigmatic painting depicts a seated female figure on an elaborate throne, her expression pensive, her form statuesque. The intricate details of her costume and the fantastical throne, adorned with dolphin-like creatures, are typical of Tura's inventive style. His depictions of saints, such as Saint Jerome in the Wilderness (National Gallery, London) or Saint Anthony of Padua (Galleria Estense, Modena), often portray them as gaunt, ascetic figures, their spiritual fervor conveyed through their emaciated forms and intense gazes, set within stark, rocky landscapes. The Madonna and Child in the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, is another fine example of his devotional panels, showcasing the cool palette and sculptural modeling that define his approach to sacred figures. These works, and others, solidify Tura's reputation as an artist of profound originality and emotional depth.

Tura and His Contemporaries: A Network of Influence

Cosimo Tura's artistic development and career unfolded within a rich tapestry of contemporary artistic movements and influential figures. His relationship with Andrea Mantegna is particularly significant. Both artists trained in Squarcione's Paduan workshop and shared an interest in classical antiquity, strong draftsmanship, and a sculptural approach to form. Mantegna's powerful compositions, mastery of perspective, and often austere figures undoubtedly influenced Tura. However, Tura's art diverged, embracing a more expressive, sometimes even tormented, quality that contrasted with Mantegna's more stoic classicism. While Mantegna's figures possess a Roman gravitas, Tura's often seem to writhe with an inner, almost Gothic, intensity.

Piero della Francesca, who worked in Ferrara during Tura's formative years, also left an impression. Piero's command of perspective, his use of clear, cool light, and the monumental, almost geometric, solemnity of his figures can be seen as a counterpoint to Tura's more agitated style. Tura may have absorbed lessons in compositional clarity and the depiction of volume from Piero, even as he infused his own work with a greater sense of drama and fantasy.

The influence of the Venetian school, particularly the Bellini family—Jacopo, Gentile, and Giovanni—is also relevant, given Ferrara's proximity to Venice and the active cultural exchange between the two cities. While Tura's hard-edged style differs markedly from the softer, more atmospheric qualities developing in Venetian painting, especially in the work of Giovanni Bellini, the Venetian emphasis on color and light may have had some impact. Jacopo Bellini's sketchbooks, with their explorations of perspective and classical motifs, were also part of the artistic currency of the time. Carlo Crivelli, another Venetian-trained artist active in the Marches, shared with Tura a taste for intricate detail, strong outlines, and expressive, sometimes eccentric, figures, suggesting a shared current within North Italian art that valued decorative richness and intense emotionalism.

Donatello's presence in Padua during Tura's youth was a seismic event for North Italian art. The raw emotional power and naturalism of Donatello's bronze sculptures, such as the Gattamelata monument and the reliefs for the Santo altar, provided a new benchmark for expressive intensity that resonated deeply with artists like Tura and Mantegna. Further afield, the work of Florentine masters like Paolo Uccello, with his obsessive experiments in perspective, or Filippo Lippi, with his lyrical grace, formed part of the broader Renaissance dialogue, though Tura's path remained distinctly Ferrarese. Even the innovations of Netherlandish painters like Rogier van der Weyden, whose works were known and admired in Italy for their meticulous realism and poignant emotionality, may have contributed to the expressive depth found in Tura's art. Antonello da Messina, who masterfully blended Netherlandish oil techniques with Italian monumentality, was another contemporary whose work highlights the diverse artistic currents of the Quattrocento.

The Ferrarese School: Tura's Foundational Role

Cosimo Tura is rightly considered the caposcuola, or head, of the Ferrarese School of painting. His distinctive style, forged in Padua and refined at the Este court, laid the groundwork for a regional artistic identity that flourished in the late 15th and early 16th centuries. The Ferrarese School, under Tura's initial impetus, became known for its expressive intensity, sharp linearity, vibrant and sometimes unusual color harmonies, and a penchant for intricate, often fantastical, detail.

Tura's direct influence can be seen in the work of his slightly younger contemporaries and successors in Ferrara. Francesco del Cossa, who collaborated with Tura on the Palazzo Schifanoia frescoes, developed a style that, while sharing Tura's robustness and sculptural quality, often displayed a greater naturalism and a slightly softer modeling. Cossa's figures possess a weighty presence, but his approach to color and light could be more nuanced than Tura's often stark contrasts.

Ercole de' Roberti, another key figure in the Ferrarese School, also worked on the Schifanoia project and likely learned from Tura. Ercole's style is characterized by an even greater nervous energy and dynamism than Tura's. His figures are often slender, agile, and imbued with a wiry tension, their movements animated and their expressions vivid. While clearly indebted to Tura's foundational work, Ercole pushed the expressive potential of the Ferrarese style in new directions, creating works of extraordinary emotional power and visual complexity.

Later Ferrarese artists, such as Lorenzo Costa, initially showed Tura's influence but gradually moved towards a softer, more harmonious style, reflecting the changing artistic tastes of the High Renaissance and the influence of painters from Bologna and Central Italy, like Perugino or Francia. However, the legacy of Tura's intense and highly personal vision remained a defining characteristic of Ferrarese art for a significant period. His ability to synthesize diverse influences—Paduan classicism, Gothic expressiveness, and local Ferrarese taste—into a coherent and powerful artistic language provided a strong foundation upon which subsequent generations of Ferrarese painters could build. The school he founded became a significant, if sometimes overlooked, contributor to the rich diversity of Italian Renaissance art.

Later Years, Financial Struggles, and Enduring Legacy

Despite his long service to the Este court and his pivotal role in establishing the Ferrarese School, Cosimo Tura's later years were marked by a decline in ducal favor and, consequently, financial hardship. By the 1480s and early 1490s, newer artistic talents and perhaps changing tastes at court meant that commissions for Tura became less frequent and less lucrative. Ercole de' Roberti, for instance, eventually succeeded him as court painter to Ercole I d'Este.

There is poignant documentary evidence of Tura's financial difficulties. A letter from 1490 reveals him pleading with Duke Ercole I for payment for a portrait of the Duke's daughter, Beatrice d'Este, complaining that he did not know "how to live and support my family." This suggests that, despite his artistic achievements, he did not amass significant wealth and faced insecurity in his old age. Cosimo Tura died in Ferrara in April 1495, at around the age of 65.

Despite these later struggles, Tura's artistic legacy is undeniable. He left an indelible mark on Ferrarese art, and his influence extended to his pupils and followers. While his highly idiosyncratic style was perhaps too personal to be directly imitated on a wide scale, the expressive intensity and imaginative power of his work resonated with later artists. Some art historians have suggested that the dramatic force and unconventional beauty found in Tura's paintings foreshadowed aspects of Mannerism and even Baroque art. The emotional depth and psychological penetration of his figures, combined with his often unsettling and fantastical settings, created a body of work that transcended mere decoration.

Though for centuries his fame was somewhat eclipsed by artists from larger centers like Florence, Venice, and Rome, the 20th century saw a renewed appreciation for Tura's unique genius. Scholars and connoisseurs rediscovered the power and originality of his art, recognizing him as a master who, while working within the broader currents of the Renaissance, forged a path that was uniquely his own. His paintings, with their blend of meticulous craftsmanship, spiritual fervor, and sometimes bizarre fantasy, continue to be studied and admired for their distinctive contribution to the Italian Renaissance. Figures like Titian, with his Venetian command of color and drama, or later, Caravaggio, with his stark realism and dramatic chiaroscuro, and even the dynamic sculptor Gian Lorenzo Bernini, all pushed boundaries of expression in ways that, while distinct, share a distant kinship with the intense artistic spirit Tura embodied in the Quattrocento. His work remains a testament to the rich regional diversity of Renaissance art and the enduring power of a singular artistic vision.

Conclusion: The Singular Vision of a Renaissance Master

Cosimo Tura remains a compelling and somewhat enigmatic figure in the annals of art history. As the principal founder of the Ferrarese School, he endowed his native city with a distinct artistic voice, one characterized by an intense, often unsettling, beauty, sharp linearity, and a deeply personal interpretation of both sacred and secular themes. His training in Padua under Squarcione, combined with the influences of giants like Donatello and Piero della Francesca, provided him with a solid technical and intellectual foundation. Yet, Tura's genius lay in his ability to synthesize these influences into a style that was unmistakably his own—a style that was at once archaic and innovative, blending Gothic expressive power with Renaissance formal concerns.

Serving the Este dukes for much of his career, Tura's art graced the chapels, palaces, and public life of Ferrara, leaving an indelible mark on the city's cultural landscape. His masterworks, from the dramatic organ shutters of Ferrara Cathedral to the poignant fragments of the Roverella Altarpiece and the enigmatic allegories of the Palazzo Schifanoia, reveal an artist of profound emotional depth and imaginative power. Though his later years were shadowed by hardship, his artistic legacy endured, shaping the development of the Ferrarese School through his influence on artists like Francesco del Cossa and Ercole de' Roberti.

Today, Cosimo Tura is recognized as a master of the Early Renaissance, an artist whose unique vision offers a fascinating counterpoint to the more celebrated schools of Florence and Venice. His work, with its metallic sheen, expressive intensity, and fantastical elements, continues to challenge and captivate, securing his place as one of the most original and compelling painters of the Italian Quattrocento.