Philipp Bauknecht, a significant yet sometimes overlooked figure in the German Expressionist movement, carved a unique artistic path defined by vibrant color, emotional intensity, and a profound connection to the Alpine landscape. Born in Barcelona, Spain, in 1884 to German parents, and passing away prematurely in Davos, Switzerland, in 1933, Bauknecht's life and art were inextricably linked with the dramatic environment that became both his sanctuary and his muse. His relatively short career produced a body of work that continues to captivate with its raw energy and distinctive visual language, standing as a testament to the enduring power of Expressionism.

Early Life and the Turn to Davos

Details of Bauknecht's earliest artistic training are not extensively documented in common records, but it is known he pursued formal art education in Stuttgart at the Royal School of Applied Arts (Königliche Kunstgewerbeschule) and later at the State Academy of Fine Arts (Staatliche Akademie der Bildenden Künste). Like many aspiring artists of his generation, he would have been exposed to the burgeoning avant-garde movements sweeping across Europe, from Post-Impressionism to Fauvism, which were challenging academic traditions and paving the way for more subjective forms of artistic expression.

A pivotal and life-altering event occurred when Bauknecht, at the young age of 26 (around 1910), was diagnosed with tuberculosis. This serious illness necessitated a move to the clearer, thinner air of the Swiss Alps. He settled in Davos, a mountain town already renowned as a health resort, famously depicted in Thomas Mann's novel The Magic Mountain. This relocation, initially for health reasons, profoundly shaped Bauknecht's artistic trajectory. The imposing mountain scenery, the local peasant culture, and the unique atmosphere of a sanatorium town provided him with a rich tapestry of subjects and emotional stimuli.

The Influence of Kirchner and the Davos Art Scene

In Davos, Bauknecht came into close contact with Ernst Ludwig Kirchner (1880-1938), one of the leading figures of German Expressionism and a founding member of the influential artists' group Die Brücke (The Bridge). Kirchner had also moved to Davos in 1917, seeking refuge and recovery from physical and psychological ailments exacerbated by his experiences in World War I. The presence of such a dynamic and established artist undoubtedly had a significant impact on Bauknecht.

While Bauknecht was never formally a member of Die Brücke – which also included artists like Erich Heckel, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, and for a time Max Pechstein and Otto Mueller – he became part of Kirchner's artistic circle in Switzerland. He participated in creative activities and discussions, absorbing the Expressionist ethos that emphasized subjective feeling over objective reality, often conveyed through distorted forms, heightened colors, and vigorous brushwork. Kirchner's own Davos work, characterized by nervous energy and depictions of both the majestic landscape and the local people, would have provided a powerful contemporary example for Bauknecht.

Bauknecht also became associated with the "Rot-Blau Gruppe" (Red-Blue Group), an artistic collective formed in Switzerland. This group, active in the 1920s, included artists such as Hermann Scherer, Albert Müller, and Paul Camenisch, with Jan Wiegers also being connected. Kirchner acted as a mentor figure to this younger generation of Swiss Expressionists. The group sought to develop a distinctly Swiss form of Expressionism, often focusing on local themes and landscapes. Bauknecht's involvement underscores his integration into the regional art scene and his commitment to the broader Expressionist current.

Artistic Style: Color, Form, and Emotional Resonance

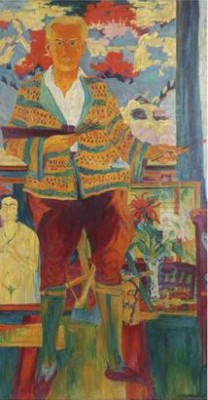

Philipp Bauknecht's style is quintessentially Expressionist. His paintings are characterized by a bold and often non-naturalistic use of color, where hues are chosen for their emotional impact rather than their descriptive accuracy. Reds, blues, yellows, and greens often appear in strong, sometimes clashing, combinations, imbuing his scenes with a heightened sense of drama and vitality. His compositions are marked by a certain spontaneity and a simplification of forms, sometimes leading to a deliberate distortion of figures and perspectives.

His brushwork is typically energetic and visible, contributing to the overall dynamism of his canvases. He was less concerned with meticulous detail and more focused on capturing the essential spirit or feeling of his subject matter. Whether depicting the rugged Alpine peaks, the hardworking local peasantry, or scenes of village life, Bauknecht's art conveys a deep empathy and an intense personal response to the world around him. This subjective approach is a hallmark of Expressionism, which sought to express inner emotional states rather than merely replicate external appearances, a path also trodden by artists like Emil Nolde with his powerful, often primal, use of color.

Influences from Italy: Segantini and Giacometti

Beyond the immediate influence of German Expressionism and Kirchner, Bauknecht's work also shows an affinity with certain Italian artists, particularly Giovanni Segantini (1858-1899) and Giovanni Giacometti (1868-1933). Segantini, an Italian painter associated with Divisionism (a technique related to Pointillism, famously practiced by Georges Seurat and Paul Signac), spent much of his later career in the Swiss Alps, near Davos in the Engadine valley. Segantini's majestic depictions of Alpine life and landscapes, rendered with a distinctive, luminous technique, were widely admired.

Bauknecht's engagement with similar subject matter – the mountains, the peasants, the animals – and his use of bright, often unmixed colors, suggest an awareness of Segantini's legacy. While Bauknecht's style is more overtly Expressionistic and less systematically Divisionist than Segantini's, the shared thematic concerns and the powerful evocation of the Alpine environment create a clear point of connection.

Giovanni Giacometti, father of the famous sculptor Alberto Giacometti and a prominent Swiss Post-Impressionist painter, was also active in the same Alpine region. Giacometti, who was himself influenced by Segantini as well as by French artists like Cuno Amiet and even Vincent van Gogh and Paul Cézanne, developed a style characterized by vibrant color and a deep connection to his native Grisons. Bauknecht's depictions of rural life and his expressive use of color align with Giacometti's artistic concerns, suggesting a shared regional sensibility, even if their stylistic paths diverged. The influence of Ferdinand Hodler, another towering figure in Swiss art known for his monumental Symbolist and landscape paintings, also permeated the artistic atmosphere of the region.

Representative Works and Dominant Themes

Bauknecht's oeuvre is rich with depictions of the Davos landscape and its inhabitants. His works often focus on themes of nature, rural labor, traditional customs, and the human condition as experienced within this specific environment.

One of his notable works is Älplerkirchweihtanz (Alpine Herdsmen's Church Festival Dance), painted around 1922. This piece exemplifies his mature Expressionist style. It portrays a lively, almost frenetic traditional dance scene. The figures are rendered with a deliberate crudeness and distortion, their bodies contorted by the energy of the dance. The colors are bold and contrasting, contributing to the painting's dynamic and somewhat unsettling atmosphere. It’s a modern artistic interpretation of a traditional folk ritual, capturing its raw vitality through an Expressionist lens.

Another significant painting is Alt Bäuerin mit Hühnern (Old Peasant Woman with Chickens), circa 1920. This work showcases Bauknecht's empathy for the local peasantry. The depiction of the elderly woman, surrounded by her chickens, is rendered with strong, simplified forms and expressive colors. There's a sense of dignity and resilience in the figure, a common theme in Bauknecht's portrayals of mountain folk. The painting avoids sentimentality, instead offering a powerful, almost iconic image of rural life.

His landscapes, often depicting the towering peaks and valleys around Davos, are imbued with a similar emotional intensity. He captured the "Magic Mountain" atmosphere, not just its physical beauty but also its psychological weight – a place of both healing and isolation. These works often feature dramatic skies and a palpable sense of the sublime power of nature, echoing the Romantic tradition but filtered through an Expressionist sensibility, much like Edvard Munch captured the anxieties of the modern soul in his landscapes.

The "Degenerate Art" Exhibition and Posthumous Fate

Philipp Bauknecht's career was tragically cut short by his death from tuberculosis in 1933, the same year the Nazi Party came to power in Germany. As an Expressionist artist, Bauknecht's work was anathema to the Nazi regime's narrow, reactionary cultural ideology, which championed a heroic, pseudo-classical realism and condemned most forms of modern art as "degenerate" (Entartete Kunst).

In 1937, the Nazis organized the infamous "Degenerate Art" exhibition in Munich. This exhibition was designed to ridicule and vilify modern art, showcasing works by many of Germany's leading avant-garde artists, including Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Emil Nolde, Max Beckmann, Paul Klee, Wassily Kandinsky, Franz Marc, August Macke, and Marc Chagall, among many others. Philipp Bauknecht's paintings were also included in this defamatory show. This posthumous condemnation meant that his work was removed from public collections in Germany and largely disappeared from view for several decades.

It was largely thanks to the efforts of his wife, Ada Bauknecht, that a significant portion of his oeuvre was preserved. She managed to protect his works from destruction by the Nazis. However, it was not until the 1960s that Bauknecht's art began to be rediscovered and re-evaluated. The post-war period saw a renewed interest in German Expressionism, and artists who had been suppressed or forgotten during the Nazi era gradually regained recognition.

Rediscovery and Legacy

In the decades following the 1960s, Philipp Bauknecht's work has been featured in various exhibitions, slowly re-establishing his place within the narrative of German Expressionism. Notably, in 2014, significant retrospective exhibitions were held at the Würth Museum in Künzelsau, Germany (though the provided text mentions Munich, it's often associated with the Sammlung Würth in Künzelsau or Schwäbisch Hall), and at the Kirchner Museum in Davos. These exhibitions played a crucial role in bringing his powerful and distinctive art to a wider contemporary audience.

His works are now found in private collections and some public museums, particularly in Switzerland and Germany. Art historians and collectors appreciate his unique contribution: an Expressionism deeply rooted in the Alpine environment, marked by intense color, emotional depth, and a focus on the human connection to nature and tradition.

Philipp Bauknecht's legacy is that of an artist who, despite a life constrained by illness and a career overshadowed by political turmoil, produced a body of work that speaks with an authentic and compelling voice. He translated the dramatic landscapes and the resilient spirit of the Davos people into a vibrant, emotionally charged visual language. His art serves as a poignant reminder of the power of human creativity to find profound expression even in the face of adversity, and his connection to the "Magic Mountain" of Davos adds a unique chapter to the rich and varied story of European Expressionism. His paintings continue to resonate, offering a window into a specific time and place, filtered through a deeply personal and powerfully expressive artistic vision.